Music is an art. Its value and longevity aren't measured in notes per second. Technique certainly has its place, as it allows you to deliver ideas fluently, but it can't be a substitute for substance. History shows that the ceiling of instrumental virtuosity is constantly on the rise, and ultimately, it's great writing that endures. I'll be looking at seven guitarists who employ techniques derived from composed music, and whose compositions warrant real appreciation and invite deeper study.

If we seek to have our musical contributions last longer than the average shelf life of an Instagram, YouTube, or TikTok video, devoting more time to honing our compositional skills and developing a unique, creative voice is a smart bet. And where better to learn than from those for whom this is their specialty?

Many compositional tendencies have become so widely used that they are now part of today's general music practice, but there are still myriad lessons to be learned and inspiration to be found in music of the masters of the Baroque, Classical, Romantic, and 20th Century.

Admittedly we don't have space here to dive deeply into any of these concepts, but I'm including suggestions for further study in each section. If anything here intrigues you, you'll have ideas for where you can go next.

Steve Morse's Counterpoint

Counterpoint is one of the oldest and most widely embraced compositional techniques in Western music. Its essence–point against point or note against note–is two or more independent lines contrasting with and enhancing each other. To achieve a level of mastery to use it fluently takes discipline. But when done well, the result is nothing short of divine. Think Bach, Vivaldi, Mozart, or Beethoven.

But even if you're apprehensive about the rabbit hole that is counterpoint, a few of the core principles can still help you write better, more interesting music.

1. Think of independence of voices. When one line is moving, the other can rest or be a longer note duration. When one line climbs, try having the other descend. Make sure both lines sound good by themselves as well as with each other.

2. Approach perfect consonances (unisons, octaves, fifths) with contrary or oblique motion. This helps the ear continue to hear the lines as independent. Thirds and sixths are your friends, so use them plentifully.

3. Try out some dissonances–but resolve them, preferably stepwise.

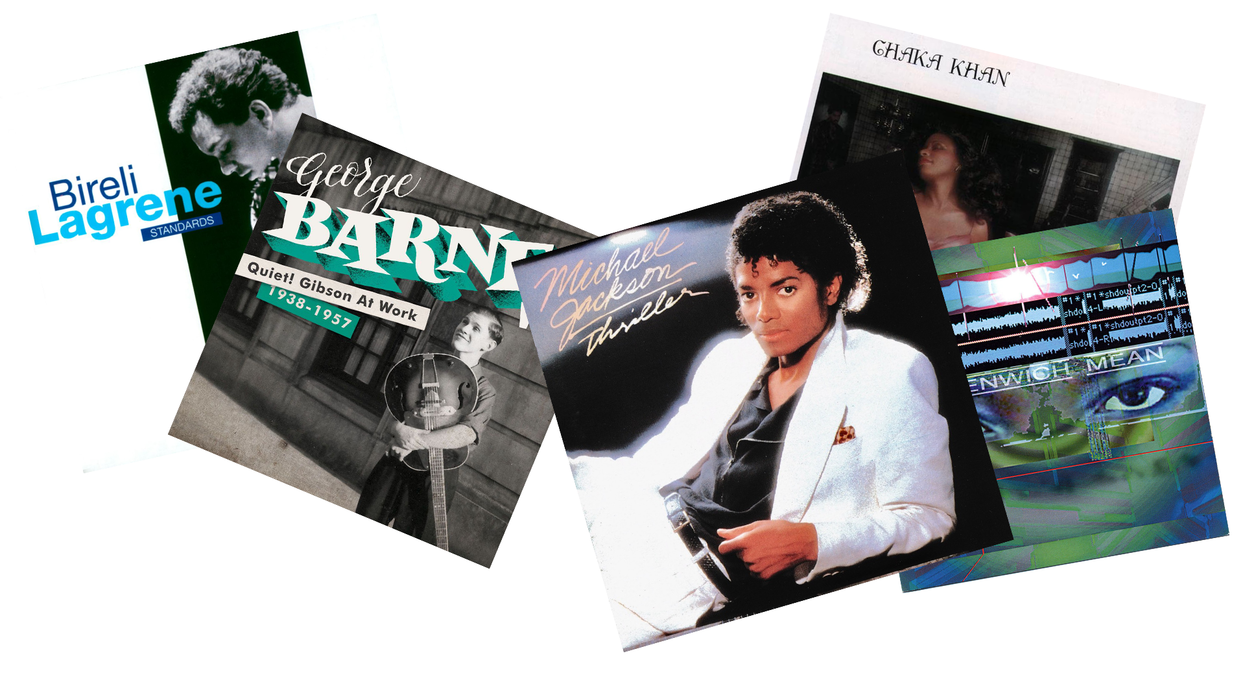

Steve Morse is one of the most sophisticated and recognizable voices in modern guitar. He uses his extensive virtuosic abilities in service of highly developed compositions. One example of his contrapuntal skills is in the aptly named "Point Counterpoint" from his album, Southern Steel. The lower voice enters with a rising motif, echoed immediately in the upper.

"Point Counterpoint"

Ex. 1 shows a basic chord progression and Ex. 2 is a short etude I wrote based on the harmony. Notice how each voice passes the melody back and forth.

Ex. 1

Ex. 2

If you want to deeper into counterpoint, check out Alan Belkin's excellent video series on YouTube. Below you can see the first installment.

On Counterpoint

Jonathan Kreisberg’s French Impressions

French impressionists and American jazz composers have a history of cross pollination. Ragtime pioneers like Scott Joplin and Jelly Roll Morton incorporated polyrhythms of African music into their piano compositions and were pioneers of a style that was the first recognizable genre of music to originate in the United States.

Ragtime made its way to Europe, and Debussy was one of the first western composers to incorporate ragtime in his music. Then, in turn, gypsy-jazz legend Django Reinhardt paid tribute to Debussy's Nuages with his own piece of the same name, integrating distinctly impressionistic whole-tone scales and modal harmonies. The languages have continued to blend, and modern jazz master Jonathan Kreisberg blends colorful chords into the characteristic sonority of French impressionistic composers.

First, let's define a few terms. A mediant relationship is when two chords are separated by a third. In the key of A that could be A and F#. Since both root notes are in the key of A we call that a diatonic mediant. If they aren't in the same key, say we have A and F natural, then that's a chromatic mediant. French composers like Debussy, Ravel, and Satie used this form of chromaticism to achieve a loose tonality, the musical counterpart of the softly representational imagery of Impressionism in the visual arts.

Now, let's get back to Kreisberg. First, watch a video of his epic piece, "Kiitos" below.

Jonathan Kreisberg Group - Kiitos |2008|

The progression that appears at the end is this:

Abmaj7/C–Abm/Cb–Bb7–Bb7–Amaj7–Fmaj7–Emaj7–Emaj7

The progression is based largely around a common note (Ab or G# enharmonically, as in Emaj7) and chromatic mediants, specifically Amaj7–Fmaj7 and Emaj7–Abmaj7.

How Do I Use This?

Try experimenting with movement up or down by a third to a chord outside the diatonic world. Ex. 3 lays out a diatonic chord progression in E major followed by various chromatic mediant options for the second chord.

Ex. 3

An important note: Your harmonic progressions will sound more convincing if you use voice leading—meaning smooth transitions between notes, moving notes as little as necessary when changing harmonies, and keeping notes in common, when possible.

Further Study:

This super artistic video by 12tone is highly recommended to learn more about how to combine seemingly unrelated chords.

When Chords Won't Share

Daniele Gottardo on 20th-Century Russian Harmony

Photo by Matt Grans

Rimsky-Korsakov, godfather of the Russian school, and his pupil, Igor Stravinsky, were on a mission to empower Russian composers to create their own nationalistic identity through blending diatonic folk melodies with chromatic, highly symmetrical harmonic devices. This sound, known as Russian Fantastic Harmony, has had widespread compositional influence. Past and current film composers draw heavily from this language.

One example of this symmetrical type of harmony is octatonic. The octatonic scale alternates half -and whole-steps, as in: B–C–D–Eb–F–F#–G#–A.

Furthermore, you can build harmonies on each scale degree, just as in diatonic harmony, with a wide array of resultant chords. Because of the equal alternation of half- and whole-steps, there is not the same sense of tonal center, so octatonic is great for creating tonal ambiguity. Significantly, you can derive four major and minor triads a minor third apart—both are options in the case of the octatonic scale. Just be on the lookout for enharmonic equivalents—Eb can also function as D#, the third of a B major triad, yet D is also present in the scale, meaning both B major and B minor are octatonic triads.

Italian maestro Daniele Gottardo cites the Rimsky school as his biggest compositional influence. In his piece, "Gingerbread House," Gottardo makes good use of triadic octatonicism.

Daniele Gottardo - Gingerbread House

How to Use This:

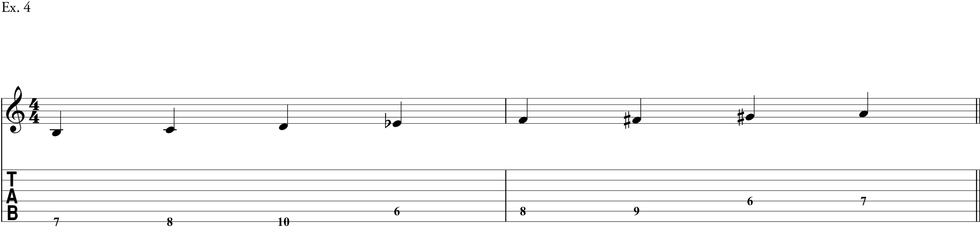

1. Pick an octatonic scale and write out the notes (Ex. 4).

2. Pick chord progression derived from the scale. Let's use Bm–Dm–Bm–G#m.

3. Add melody notes and passing tones using your ears and instincts within this environment.

Ex. 4

Ex. 5 shows a Gottardo-inspired octatonic line, incorporating tapped notes.

Ex. 5

Fugues and J.S. Bach

Certain musical practices have earned an enduring place in musical history, even if used less popularly. The fugue is almost synonymous with J.S. Bach, and the highly complex, imitative texture delights us still today. Yet composing one requires rigorous study and highly cultivated counterpoint skills.

A fugue is a compositional procedure based on imitation in which a small musical phrase is introduced and taken over by other voices working in counterpoint.

Bulgarian guitarist, multi-instrumentalist, and composer Alexandra Zerner composed a fugue, "Triangulum," in tribute to J.S. Bach.

Alexandra Zerner | Triangulum (Playthrough)

If fully immersing yourself in the discipline feels daunting, there are still components of fugal composition than can enhance your writing:

1. Imitation

2. Contrast of keys

3. Architecture of musical density and texture

How to Use This:

1. Start with writing a canon—a musical idea that is stated and then gets echoed by another part.

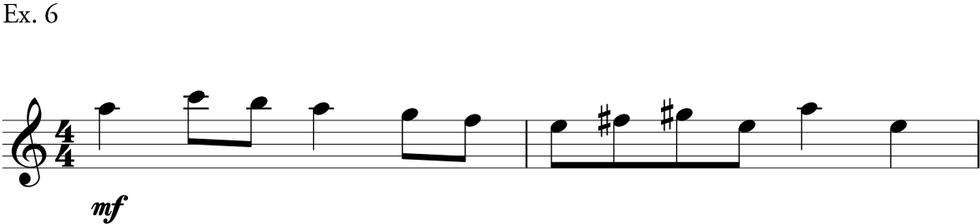

2. Write one measure for voice 1. (Ex. 6)

Ex. 6

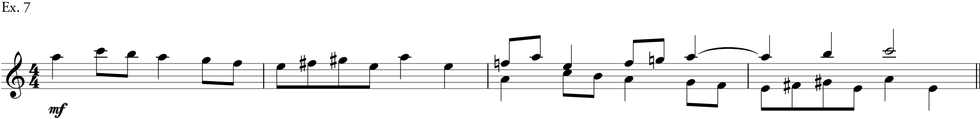

3. Copy it to voice 2 (transposing by octave is fine) and continue voice 1 by writing a counterpoint to voice 2. (Ex. 7)

Ex. 7

4. Copy the counterpoint to voice 2, and write a counterpoint in voice 1.

5. Continue in this way, until you reach a logical cadence or end of a musical phrase. Ideally the separate voices of the canon should work well together as well as on their own. Ex. 8 shows a short canon idea.

6. This process can also be effective with less rigid imitation—try retaining the basic shape and rhythm of a melody while transposing notes as necessary for harmonic purposes (a process known as free imitation).

Ex. 8

We Need to Talk About Yngwie

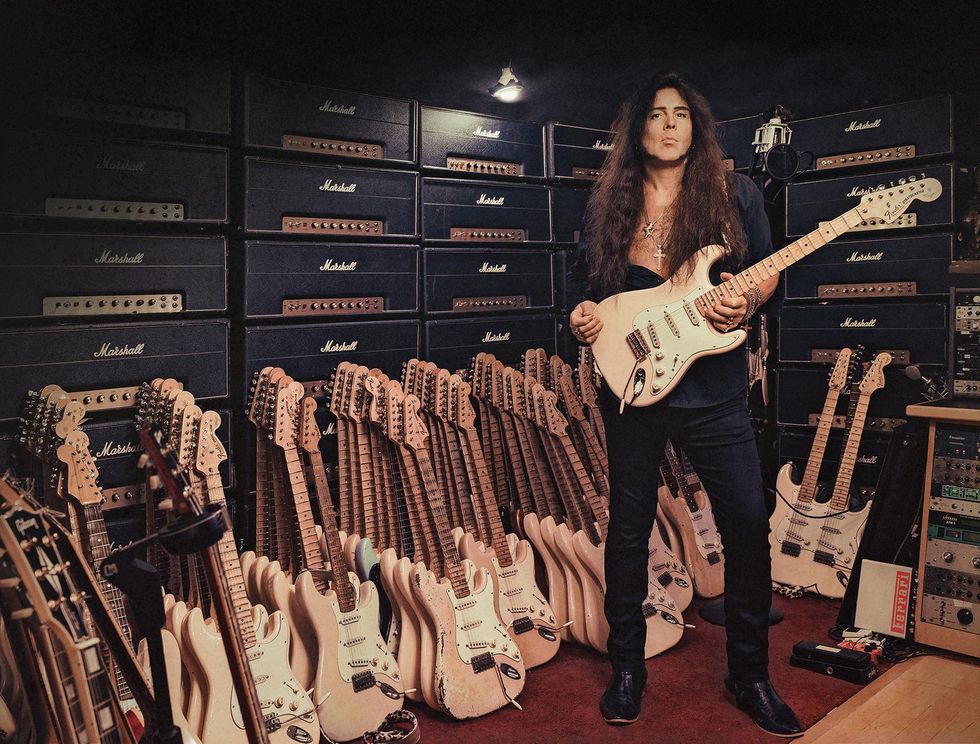

Photo by Austin Hargrave

Hilarious quotes aside, Yngwie's combination of tone, technique, and neo-classical shred that celebrates the masters make his musical contribution no laughing matter. The use of the harmonic minor alone wouldn't really justify inclusion here, but combined with baroque-approved chord progressions, intelligent melodic sequences, and Paganini-like technique, we must shine a light on Yngwie's incredible playing.

The sound most identified with Yngwie is the harmonic minor scale, which is simply a natural minor scale with a raised 7, or you can think of it as a major scale with a flat 3 and flat 6.

How to Use This:

Try combining a traditional minor chord progression with arpeggios or a melodic sequence, and make sure you throw in the raised 7, especially when you get to the dominant chord.

In Ex. 9, we have a minor progression outlined by arpeggios a la Yngwie. Notice the raised 7 (B) in three out of the four measures, functioning both as a leading tone to approach the root and as a note of the harmony.

Ex. 9

For Further Study:

Here's a great breakdown on minor scales from Seth Monahan.

Lesson 3: Minor Scales

A good gateway into Yngwie's catalog is "Far Beyond the Sun."

Yngwie Malmsteen - Far Beyond the Sun LIVE

Frank Zappa’s 12-Tone Rows

With the emancipation of dissonance and the treatment of all notes as equals, Schoenberg pushed ears and aesthetics of the time to (and past) the limit. Zappa similarly challenged, delighted, and sometimes enraged listeners and critics. Both were creatively shocking, forward thinking, and managed to forge unmistakable voices. Zappa's contribution as a legitimate and brilliant late 20th-century composer is becoming ever more widely recognized, and his music displayed a deep understanding of complex and varied compositional techniques. Let's look at just one: the 12-tone row.

A 12-tone row is a concept of serialism in music. It is the practical extension of the concept of all notes being treated equally and consists of a composer putting the 12 notes of the chromatic scale in a particular sequence. No note is repeated until the row completes. The series becomes the unifying element of the piece, rather than functional tonality.

"Waltz for Guitar" is a composition that Zappa wrote when he was 18. The tone row he uses is:

G–F#–A–A#–E–G#–D–D#–B–F–C–C#

Frank Zappa - Waltz for Guitar (1958) (score/audio)

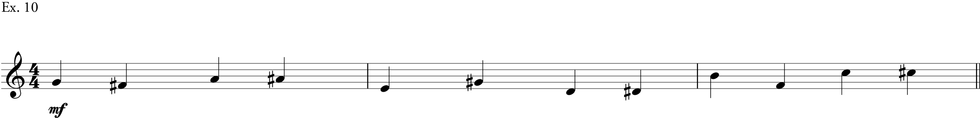

The system might feel rigid or the results a bit dissonant for many, but, as with any technique, it can be useful to try it out and see where it leads you. Anything that pushes us into new territory is a great way to encourage artistic revelations, or at least growth. Ex. 10 shows Zappa's 12-tone row.

Ex. 10

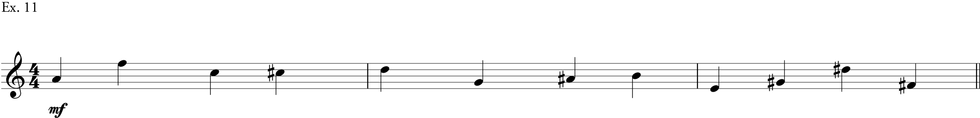

To better demonstrate how to manipulate this technique, I came up with Ex. 11, an original tone row I composed.

Ex. 11

I then took the row and came up with a way of delivering that felt that there was some rhythmic interest and cohesion (Ex. 12). I made the choice to have the pitches shift within the rhythm, so that while the rhythm laid out in the first three measures starts again in measure 4, the starting pitch is the last note of the tone row (F#), so everything shifts rhythmically by one note.

But give it a go and be as strict as serves you and your muses.

Ex. 12

Steven Mackey’s Polyrhythms

In addition to being an award-winning composer, Steven Mackey is an electric guitar player whose roots are in rock and blues. Of all the guitarists on this list, he is most fully integrated in the world of serious composition and has been at the forefront of incorporating the electric guitar in unconventional contexts.

You could pick any aspect of composition and find it in Mackey's work. Here we will highlight the use of polyphony and polyrhythm.

Polyphony is a musical texture with multiple, simultaneous voices in independent, complementary melodies. Polyrhythm is the simultaneous juxtaposition of beat groups that are not subdivisions of each other, for example, triplets against eighth-notes.

In the second movement of Mackey's piece for guitar and orchestra, Tuck and Roll, a delightfully wacky guitar part combines both polyphony and polyrhythm in a 5/8 figure against half-note triplets within 4/4 time.

Tuck and Roll: Dark Caprice

I had the pleasure of talking with Steven Mackey about this, and here is how he would advise someone new to this concept to approach creating with it.

1. Start away from your instrument and get used to tapping simple polyrhythms with both hands, such as 2 against 3, 3 against 4, 2 against 5.

2. Apply the polyrhythm to two adjacent strings on the guitar, with each string assigned one part of the meter. Ex. 13 shows a figure of 2 on the 3rd string and 3 on the 4th string. Work on getting the rhythm first—it's very helpful to use a slow click (60 BPM or so). Then start moving notes around to create melodies.

Ex. 13

3.Then try Ex. 14 and Ex. 15, using the same method of getting it in your ears first, then under your fingers in a rudimentary way with static notes on adjacent strings. Then move on to adding melodic movement.

Ex. 14

Ex. 15

4. Once you have really internalized this concept, you can take it across more strings, and move freely.

Good luck with this! The idea with any technique—whether it pertains to your instrument or your composing—is to put it in service of creativity. Developing a new skill requires investment to reap the benefits, so stay patient with aspects that feel laborious. Challenge is how we grow, and the goal is not to recreationally restrict your muses, but to broaden and enrich your palette. If some of these techniques seem cerebral or confining, remember that you have the freedom to use them to the degree that suits you. And you never know… sticking with it a bit longer than is easy or comfortable just might result in something you'd have never written otherwise. I encourage you to stay curious, courageous, and shameless as you discover what is uniquely you in your artistic expressions.