There’s a battle being waged in John Frusciante’s mind. In his musical world of juxtapositions and genre marriages, the traditional spars with the far-out, and mathematical equations somehow compute into expressions of feeling. The guitar will always be a bedrock instrument for the former Red Hot Chili Pepper, but his new weapons of choice are machines. “The Roland MC-202 [an early-’80s synthesizer/sequencer] is one of my favorite instruments,” he says. “The same goes for drum machines, samplers, the computer, and other synthesizers.”

For Frusciante, the main appeal of these instruments is that once you learn to manipulate them, you can produce all types of instrumental sounds instantly. Frusciante actually has six MC-202s, which he uses in various combinations to translate guitar parts into synthesized parts. With multiple machines, he can manipulate a single guitar string per machine, and then endlessly refine each string’s sound.

“At this point I’m as fluent in programming as I am on guitar,” he says. “Since I’ve learned the language and integrated it with my natural tendencies as a musician, it sometimes feels like I’m a commander in a war. Like there’s fu**ed-up shit going on, and I have to fix it. Like there are two sides arguing, and one side has to win and one side has to lose. One side has to be captured and enslaved to the other side. In some ways it’s probably not that different from playing a war video game. I read books about subjects like war because they remind me of how I think when I make music.”

Frusciante emphasizes the fact that programmed instruments are “obedient to the mind”— a composer’s most important instrument. He now feels there are no physical obstacles between the music in his imagination and the sounds he creates. He says he’s equally inspired by 20th-century classical composers such as Igor Stravinsky and Iannis Xenakis, and more recent electronic experimentalists like Tom “Squarepusher” Jenkinson, who is both a classical bass virtuoso and a master programmer.

about music in intellectual terms.”

Frusciante says he was introduced to electronic music when he formed Speed Dealer Moms, an “experimental acid house” group, with friends Aaron Funk and Chris McDonald. Six years later, Frusciante has released Enclosure, his 11th solo album, which relies heavily on programming. He views it as a personal musical breakthrough, a marriage of intricate guitar compositions and the electronica knowledge he acquired while creating prior albums like The Empyrean and PBX Funicular Intaglio Zone.

“It’s a great time to be a musician,” says the prolific Frusciante. He tells Premier Guitar why he feels so strongly about that while candidly describing his recent music-making process.

Can you tell us how you fell in love with guitar and why you wanted to play?

When I was a little kid, it seemed clear that if I learned how to play an instrument, I’d be able to play the music I heard in my head, music I’d never heard in the real world. My parents wouldn't get me an electric guitar, though. I tried to start playing when I was 7, but I thought acoustic was boring—it wasn’t the sound that I wanted to hear. I managed to get an electric guitar when I was 12. As a little kid in Santa Monica, Led Zeppelin and Kiss were the big things. I would hear Jimmy Page and wonder how a person’s hands could get those sounds. Guitar for me has always been about the sound of the instrument, not the physicality. Physicality is just this thing between your imagination and the sound that comes out.

Is expression the same for you on all instruments? Or is guitar a special tool?

The guitar is the best way for me to study other people’s music. Since I started playing, I’ve probably spent more time learning off records than doing any other activity in life. Doing that has so many values, among them the ability to think about music in intellectual terms. Not just hearing what you like and enjoy, but analyzing it and getting inside the heads of the people who played or wrote it. I like learning all the parts of a piece of music so I really know why I feel what I feel in the best terms that my mind is capable of understanding. I like to play one of the parts, but be able to visualize the rest of the parts and think about their relationship to each other in terms of intervals and rhythmic spaces.

John Frusciante's Gear

Guitars

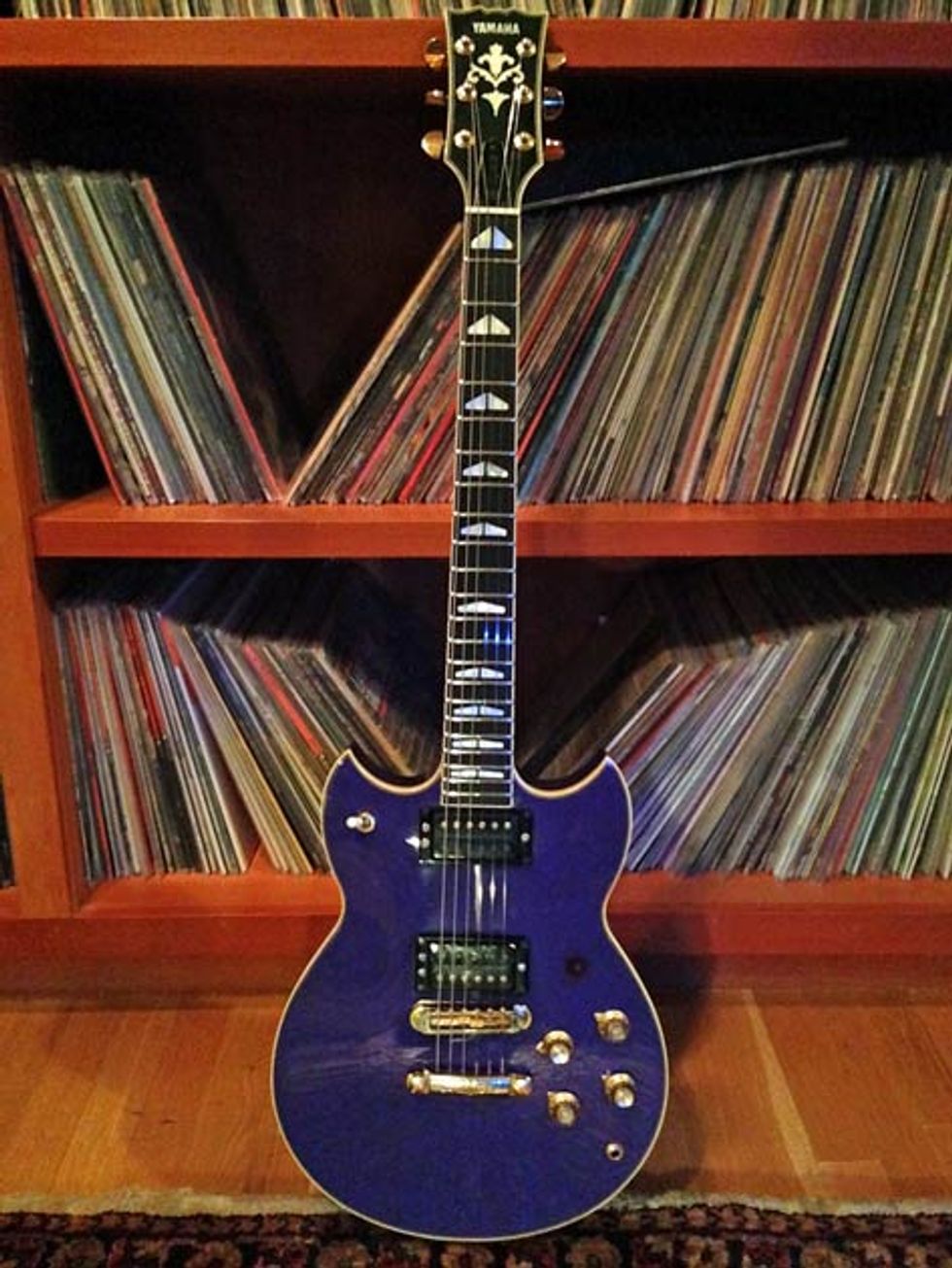

Yamaha SG2000s

Yamaha SG1500s

Ibanez Artist

Fender Bass VI

’62 Sunburst Stratocaster

Amps

Marshall Jubilee

Other Gear and Effects

Six Roland MC-202s

Roland 100-M

Roland TR-606

Roland GR-500

Roland GR-300

Tap Audio modular synthesizer

Synton Fenix modular synthesizer

Elektron Monomachine

Various vintage drum machines

Four Mackie mixers

Neve console

Electro-Harmonix Stereo Electric Mistress flanger/chorus

Pyramid light-guage strings

Dunlop Tortex picks .60 mm

In a statement attached to your Outsides EP, you said, “Rock music is electronic music.” What do you mean?

Traditional musicians have this prejudice that if someone’s not physically doing something you can see, then they aren’t a legitimate musician. That’s just ignorance. In the years 1500, 1600, 1700, or 1800, those at the top of the musical hierarchy were composers. And composers weren’t doing anything that people would gawk at—they thought of music in their minds and had tools at their disposal to create it, the most powerful tool being music notation. Instrumentalists served at the pleasure of the composer. They were not like lead guitarists today. A great violinist was somebody who performed the music of great composers, and if they stood out for having particularly expressive technique, they might be featured in a concerto or something. Traditional musicians get lost in thinking that the physicality of an instrument has some inherent value unto itself.

You’re a technically gifted guitarist—but would you say you’re more of a “gut” player?

When I was growing up I had a guitar teacher who told me that because I couldn't play scales picking every note fast, I wasn’t a good guitarist. I think that attitude is wrong. For one thing, I don't think picking every note sounds very good. I know from chopping up samples that the beginning of a guitar note is the sound of the pick, and it lasts a pretty long time. If you pick every note and play very fast, you hear what people like Yngwie sound like. I love Yngwie’s playing, but it’s not the greatest sound to be picking every note, because you hear more of the pick attack than the sound of the note. Allan Holdsworth doesn’t pick every note, and I consider it a more expressive way to play fast. There’s more tonal variety. There’s more room for expression. In the ’80s, guitarists thought that because somebody played cleanly, or could pick every note fast, or do a lot of fancy tricks, that made them a good guitar player. Guitar playing got lost on that road to a certain degree. It’s not as if being studious and practicing are not advantageous for a guitar player—they are! But the goals are to see the instrument clearly in your mind, produce beautiful music, and express something.

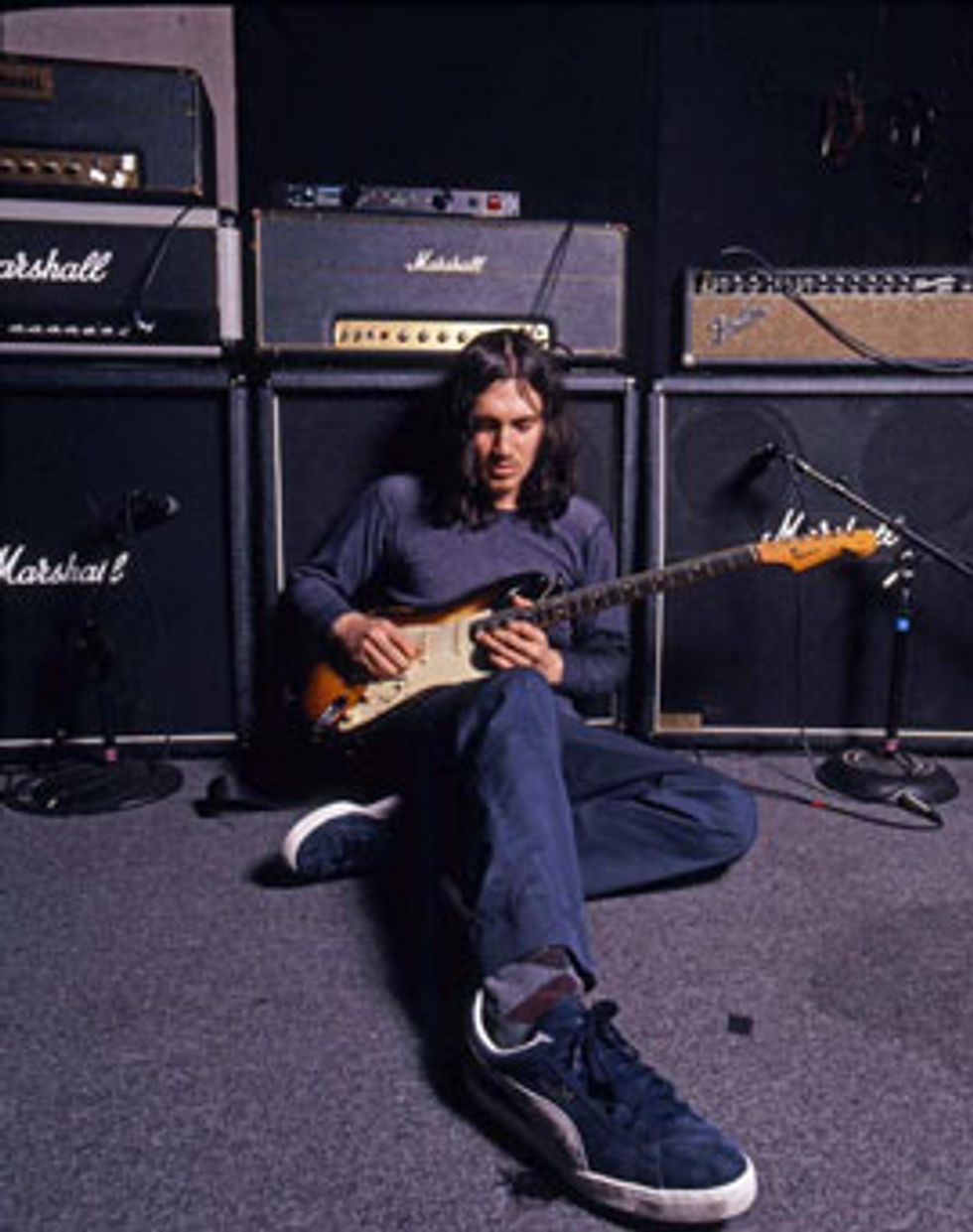

Inside Frusciante's home studio—where Enclosure was hatched.

I remember when I made the transition to following my heart: I was listening to the Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil” solo, and I thought, “This is good guitar playing.” In no way is something by Steve Vai better just because he does fancier things or because his muscles are stronger. This music coming out of this guitar is as good as music can be. Television’s Marquee Moon album gave me a similar feeling. They weren’t particularly muscular players, but it’s a very guitar-oriented record. There’s lots of soloing, and it’s beautiful music. I realized that I didn’t have to put so much intention into my playing, and that I didn’t have to make impressing the listener such a focal point of my practicing and performing. That’s the reason I played the way that I did on Blood Sugar Sex Magik and my first solo album. I was specifically not trying to be impressive, but to command the relationship between my imagination and the instrument.

How did you conceptually select songs for Enclosure?

My object was not to feature my songs, but to use the songs as a place to express myself sonically and rhythmically, with the drums as the primary instrument—more so than the melody. That’s really the change that’s taken place in the last 30 years in electronic-based forms of music. Drums have moved to the top of the hierarchy of musical elements, and typical chord changes or other elements aren’t a necessity in making music. In some ways I can go farther out than I’d be able to go if I didn’t have a song beneath me. For instance, the stuff I’ve done with chopping up jazz drum solos, doing drums that are in time with the song on certain accents and off time on other hits. I haven’t heard anybody go that far with sampling and chopping up off-time drums.

Like on “Crowded”?

Yeah, for sure. I’m particularly proud of that song. I felt like I’d reached my peak.

So some of those drums sound live, but aren’t?

No, they’re chopped-up breakbeats, where you take a recording of something like the famous “amen break” and chop it into as many pieces as possible. It’s just like slicing tape, only you’re able to cut much more precisely. Rearranging the order, changing the speed, changing the sound—it’s an area of expression absolutely equal to playing an instrument. Composers have never had the opportunity to be so detailed with rhythm. People working with tape could never edit with such rhythmic precision. It’s an incredible thing to be able to do. God, if I would have known how to do this when I was a teenager, I would’ve been so happy!

Now I do the opposite.”

But it’s probably not easy for everyone to grasp! It sounds complex.

It’s just like anything else: You practice for about five years, and it’s not hard anymore. Your mind starts forming a sense of groove. For a traditional musician, groove is something you feel, not something you think about. Boy, the struggles people have with teaching people how to have better groove—it’s like they don’t have the language for it. I have my own numerical form of theory, and I could never stop learning from it. As much as there will always be things for me to figure out on my guitar off of CDs, there will always be things to study on the computer when it comes to groove and programming and being fully conscious of the degrees of “off-timeness.” That's what groove is: varying degrees of off-timeness and varying degrees of accent and non-accent. There’s just tons to study there.

Speaking of "off-timeness," you have a knack for creating tension—like when you sing against the tempo of your songs. How do you approach this?

For Enclosure, the vocals were recorded before the instrumentation was complete. I’d start a song by programming a really simple one- or two-bar drum-machine thing, just a steady guide to sing and play guitar to. That could have been a problem, because normally people sing to fit the atmosphere that’s there, and if there’s only a guitar and a simple drum machine they’d tend to sing timidly. I learned not to do that. That initial vocal take you hear on the record is me giving my all.

The New Style

John Frusciante is pumped up about a project he just wrapped with the Black Knights, a hip-hop duo featuring Wu-Tang affiliates Crisis the Sharpshoota and Rugged Monk. At first it was just friends hanging out and rapping over beats, but eventually the songs grew into a trilogy of albums (to be released at six-month intervals) and a new way for Frusciante to make music socially. He created the soundscapes for the Black Knights’ lyrics.

“I discovered a new type of band/collaboration,” says Frusciante. “It’s really fun, and I'm as free as when I’m working alone. We have arguments all the time, but they take place within the music.”

The first of these albums, Medieval Chamber, appeared in January. According to Crisis, Medieval Chamber represents the musicians getting to know each other musically, but the trio really hits its stride with the second album, The Almighty (due this summer).

“John is so musically inclined,” says Crisis. “I learn something every time we hang out on the music tip. It’s like rapping with a band. All his beats really have feeling, and that’s what’s missing from hip-hop right now. It’s easy to catch a concept from them, too.”

Frusciante produces, plays guitar, and uses his own vocals as samples. Says Crisis: “John puts beats together beautifully. He engineers the session, cleans it up, and gives it its own feel and own world beautifully. He plays the guitar beautifully. He sings beautifully. Whatever he brings to the table, we’re all for it!”

There’s still a lot of guitar on this album. Do you use rhythm guitar as a tracking guide before laying down other parts?

Yes, I’d record the guitar as a basis for everything else, but then I’d think purely in terms of sonic composition and try to move away from the initial concept.

What are you doing with the guitar parts on “Cinch”? It’s basically a six-minute guitar solo.

I was most interested in learning to see the guitar more like a piano player sees a keyboard. Certain things that come naturally to keyboardists don’t come naturally to guitarists. Inverting chords is really easy on piano, because the notes look the same in every register, but on guitar you need to work in various positions on various areas of the neck. For instance, one of my favorite musicians is Tony Banks, the keyboard player from Genesis. I’ve loved his music my whole life, but I couldn’t write chord progressions like the things he did on The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway and Foxtrot. It was mysterious to me because I had a deep emotional connection to the music, but I couldn't learn it on guitar. I definitely couldn’t write things along those lines! It’s basically this swift ability to be able to modulate, to shift from one key or mode to another in the midst of a chord progression.

I was stuck writing chord progressions that shared the same seven notes, like Am-C-G-F-Em. If you move to D major, something has shifted—what was F is now F#. That can be inconvenient when you’re soloing, because you’re liable to make mistakes and make an idiot of yourself.

One of my rules was to not use the low strings as a guide to what key I’m in, like “B minor equals 7th fret, G minor equals 3rd fret.” In songs like “Cinch,” there’s a modulation on almost every chord. But just because my tonal center changes doesn’t mean I have to move to a different fret. When I was in the Chili Peppers, I made the chord changes I soloed over easy so I didn’t have to keep switching keys. Now I do the opposite.

Frusciante's main axe—a Yamaha SG2000—that he used during the Enclosure sessions.

What guitars did you use on Enclosure?

My main guitars are Yamaha SG2000s. My favorite is a purple one from 1980. I have a few others, and a few SG1500s. I switched from the Strat to the Yamahas in late 2010. I’ve played the Strat once in the last three years, and only on one little recording.

Why did you switch?

A guitar makes you play a certain way. A person who studies Jimi Hendrix’s playing with a Les Paul is at a disadvantage—you won’t really understand what he was doing with his hands. The way the instrument’s harmonics respond to the movement doesn’t have anything in common with what you hear on the record. A [Yamaha] SG is a lot like a Les Paul—it has a similar sound and responds to the hands in a similar way. It was an opportunity to change my style. I was looking for a way to have a new approach to the guitar, and at one point I thought of not using a pick. But the problem with that was that I couldn’t play along with records, because only two guitarists I like play without a pick.

Who?

Lindsey Buckingham from Fleetwood Mac, and Jeff Beck, who apparently hasn’t used a pick in 20 years. Those guys get such a wide range of sounds, but it would be impossible for me, because I don’t practice by playing in bands, but by playing along with records. I’m sure those guys could play along with anybody, but it would’ve taken me years to be able to do that. So I bought an SG, because I’m a big fan of John McGeoch from Siouxsie and the Banshees and Magazine. When I’d play along with his records using a Strat, the parts sounded too thin and weak for the simple power of his playing. In learning the SG, I had to teach myself to bend in a brand-new way and use new muscles to do vibrato. Everything had to change. I felt totally incapable on the guitar—it lowered my technique significantly. Where I could pick up a Strat and attack it, I couldn't do anything with the SG.

Is one of those subtle guitar parts on “Fanfare” a bass?

I play a Fender Bass VI on that song—and a Strat, I think. The Bass VI is a bass that feels like a guitar. The strings aren’t wide apart, and it has a guitar-like sound compared to a bass. You can play open chords—anything you can play on guitar sounds nice on it. The “Fanfare” guitar part is very basic chord progressions compared to most of the stuff that I do. But playing the same stuff that I played on the Strat on the Bass VI gave it a weightier sound that made it harder for my ears to decipher exactly what chords I was hearing. You’re not used to hearing those chords an octave lower.

Do you have a pedalboard in your studio right now?

No. If I want to change the sound of the guitar, I do it with the modular synthesizer. When I record, I just want to get the best pure guitar sound I can. Later, I decide whether to put some room on it, or put it through the synthesizer, or treat it with the computer in some way.

Photo by Neil Zlozower.

So are you using any traditional pedals?

Occasionally, I use an Electro-Harmonix Electric Mistress or maybe a chorus pedal. Let me see … [opens drawer] I have nice drawers with all my effects in them, but I hardly ever use them. With the Strat I had to use a distortion, but with the Yahama SG I don’t need a pedal because the amp gives me plenty of distortion. With Marshalls and a Strat, you need a distortion pedal. I use a chorus or flanger if I want a thin sound or some entertaining movement. Treating guitar with the modular [synth] after using chorus is also a nice sound.

What makes for an exciting guitar player?

Somebody who’s not conscious only of themself, but of the spatial relationships between themself and the other musicians. Someone who covers their own area sonically, rhythmically, and in terms of pitch. You can have that whether you play in an advanced style or a pretty basic one. There are great guitar players—like Matthew Ashman from Bow Wow Wow—who provide “land” that the other musicians run on and drive on and do all the stuff they do. That’s the part of guitar playing that gets overlooked by guitarists who get obsessed with technique: using the instrument to create a bed or an atmosphere for the other instruments. Steve Hackett was really great at creating guitar atmospheres that fit perfectly in the midst of Genesis’ music. And like most guitarists, I find it exciting to hear somebody going out on a limb, taking risks, and pushing themself.

Have you met anyone who’s doing what you’re doing?

Everything I’ve learned on these electronic instruments, I had the honor of learning from Aaron Funk, who goes by the name Venetian Snares. He’s not a traditional musician, but he uses a lot of the same gear I use. Along with our friend Chris [McDonald], we used to get together three or four times a year, starting in 2008. We’d live together for two weeks at a time, basically doing nothing but drinking beer and making music. But I don’t know anybody who’s both a traditional and electronic musician, except maybe Squarepusher.

Have the things you've wanted to say as a musician changed over the years?

It was always about making music that I had a thirst for—not entertaining or being popular. I let the world decide whether or not what I did would yield money. I fell in with very ambitious people and I felt like I had to coordinate my musical thinking with theirs, because they really had a drive to be popular. When I joined the Chili Peppers, they were playing clubs and selling 80,000 records. I thought they would never be any bigger, and I was shocked when I found out that they wanted to be. In a band like that, you have to compromise a lot and spend a lot of time doing things you don’t want to do, like promoting and touring the world for years.

The first time I was in the band I was confused by all that, but by the second time I had it clear in my head who they were, who I was, and how the two things could work together. The answer was for me to spend as much time as possible practicing guitar and using the leisure time to write songs and record music. When we did Blood Sugar Sex Magik, I started working on the 4-track, making music specifically for me in order to stay sane.

What was your favorite part about making Enclosure?

I guess just the feeling that I’m always discovering something. That’s what makes me want to do music in the first place. It just feels good when you can blend different genres that seem to have been segregated from one another in history. Blending them successfully is just a joy.

I feel like there’s a big message in Enclosure, that this is a way songwriters can express themselves without having to depend on producers or engineers or other musicians. Your job as a songwriter can be to create a sound composition in a way that traditional musicians can’t conceive. They know how to play their physical instrument, but when it comes to the actual goal of being a musician—creating a sonic composition—they rely on other people to do it for them.

Around the time I was making [2009's] Empyrean, I’d envisioned certain things, like the idea that jungle beats and slow, Black Sabbath-type heavy metal would go really good together. I saw how really slow music and really fast drums might intersect, but I had no capability to do it. When I finally felt I’d achieved it, it felt like I’d done something. Being in the creative process is my favorite part of anything I do. I really love the act of making music.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)