Ambient guitar means different things to different players, which suggests that there is a wide range of approaches to this rather ambiguous genre. In this lesson we'll explore an array of diverse stylistic practices within the idiom and discover how to create ambient music using the guitar.

"Ambient music must be as ignorable as it is interesting." —Brian Eno

Furniture Music?

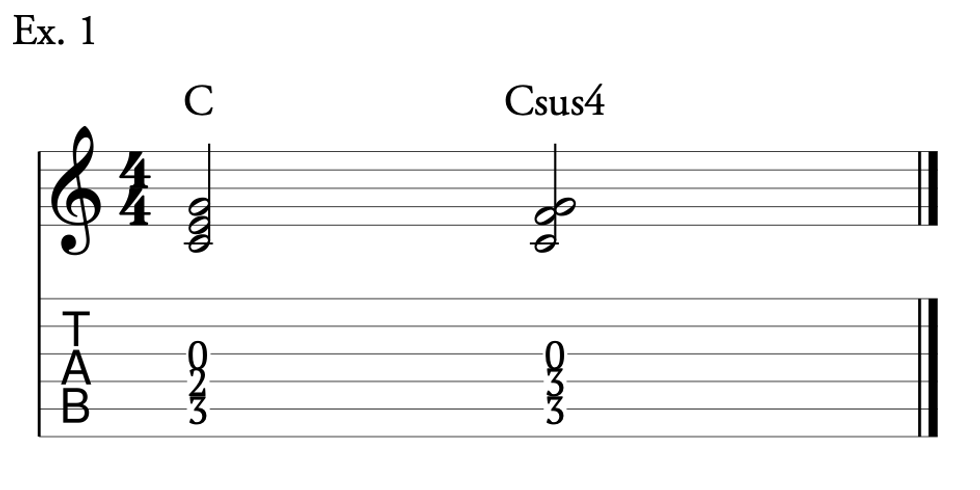

Like many genres, the origins of ambient music—and especially ambient guitar—can be difficult to determine. Nevertheless, it's safe to say that Erik Satie's Musique d'Ameublement ("furniture music") —a term the French composer coined in 1917—plays a role in the genesis of ambient music. Rather than being the center of attention, Satie wanted this music to create an atmosphere for various activities, such as the arrival of guests at a reception or eating lunch. Two of Satie's 1917 pieces, Tapisserie en fer forge and Carrelage phonique exemplify his "furniture music." The pieces would be scored for a small group of chamber orchestra instruments and consist of short phrases that are repeated an indefinite number of times. Ex. 1 is an homage to the aforementioned pieces, performed on three acoustic guitars and one bass.

Ex. 1

John Cage

No, not 4′33″—we won't get that ambient in this lesson, though now that I think of it, it probably couldn't hurt for you to stop playing for four minutes and thirty-three seconds and just listen.

How was it?

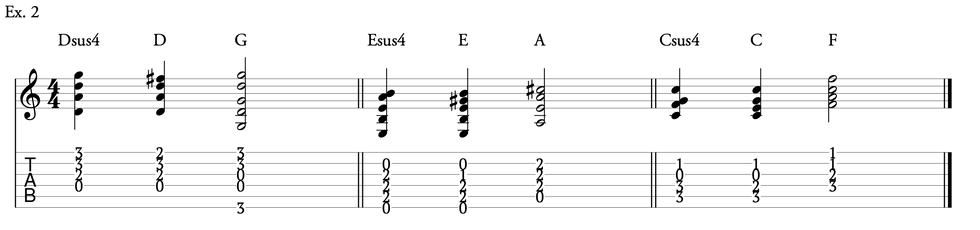

Erik Satie was a huge influence on John Cage, who referenced Satie frequently in both his public and private life. The Cage pieces I associate with ambient music (and which, to my ear at least, appear to be influenced specifically by Satie's furniture music) are "In a Landscape" and "Dream." Both were composed for solo piano in 1948. I highly recommend the John Schneider (guitar) and Amy Shulman (harp) recordings of these two pieces on the album Just West Coast. Akin to Satie's minimalist compositions, these two works of Cage's also consist of short repetitive phrases, albeit with more variations. Ex. 2, performed on a nylon-string acoustic guitar, imitates the ambient character of Cage's "Dream."

Ex. 2

The San Francisco Tape Music Center

Loops are among the fundamental tools used in generating ambient music. But the birth of looping goes back much farther than the popularizing of reliable looping pedals in the 1990s or even the long delay times used in the 1970s. Dating back to at least the 1940s with the experimentation of Pierre Schaeffer, and even Les Paul who performed live looping on television, tape loops became commonplace in the 1960s. This was in large part thanks to the San Francisco Tape Music Center (SFTMC). Founded in 1962 by composers Pauline Oliveros, Morton Subotnick, and Ramon Sender, the SFTMC pioneered many of today's looping practices, perhaps most notably SFTMC member Terry Riley's innovation of the delay/feedback system using two tape recorders. I'm simplifying here, but the basic idea behind this technique, which Riley dubbed the "Time Lag Accumulator," is to play two identical tape loops at the same time, adding delay to one of the loops, varying the delay parameters, and I believe, manipulating the tape speed.

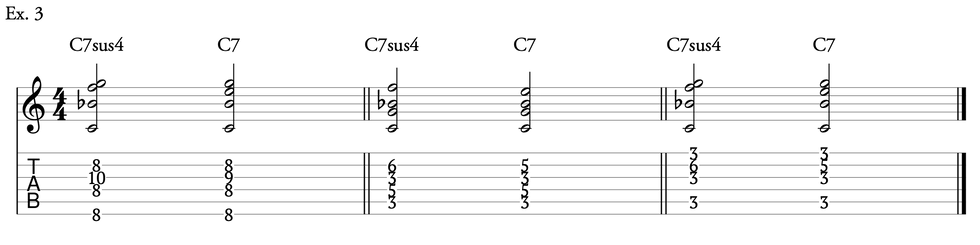

Depending on the music recorded on the original loop, the Time Lag Accumulator results can become chaotic. For ambient music, it would be best if the loop material is minimalistic. Thus, Ex. 3 is based on Riley's original premise but with significant deviations. First, keeping the ambient genre in mind, my original signal has substantial amounts of reverb and delay. I'm also swelling into my chords with my volume knob (more on that later). Most importantly, I'm using two loop pedals, not tape loops, the first feeding into the second, with a delay pedal in between the two. As a result, it is the first loop that is being affected by the delay.

The notation for this example only shows the original four-measure phrase I performed into the first looper. Once I recorded the original signal, I began manipulating the delay pedal's time, level, and feedback. Due to the intricacy of the outcomes from this technique, the music generated by the delay loop is not notated.

Ex. 3

No Pussyfooting

Yes, it's finally time for Robert Fripp and Brian Eno. This section might be what some of you have been waiting for: more familiar—dare I say more popular—ambient guitar. In 1973, Fripp and Eno released (No Pussyfooting), an album that was recorded using techniques akin, if not identical, to Oliveros' and Riley's experiments with tape loops at the San Francisco Tape Music Center years earlier. (No Pussyfooting) has since become a landmark recording for ambient music fans, and it ultimately led Fripp to dub his tape-based technique "Frippertronics" and for Eno to describe what they created as "ambient music."

Besides Eno's manipulation of the loops, Fripp introduced two specific concepts on (No Pussyfooting) that are now pervasive in ambient guitar. The first is to create a droning, slow-moving loop as accompaniment to solo over. The second is Fripp's soloing style, which tends to consist of long, sustained notes that sound more like a synthesizer than a guitar.

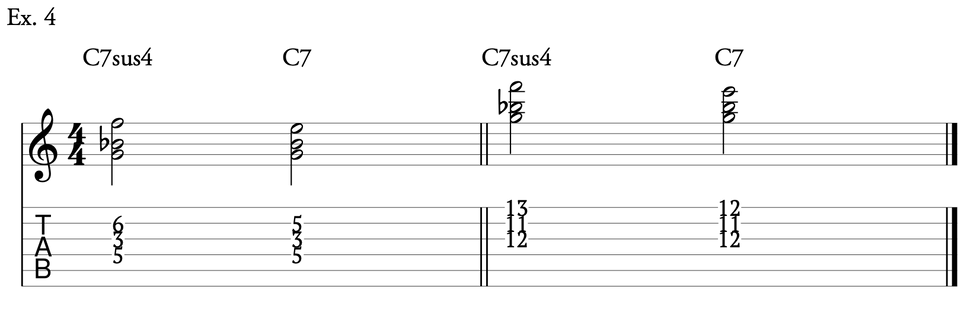

Ex. 4 imitates the Frippertronics style. It features a droning loop with a constant C bass and additional notes that imply a C to D/C chord progression. Technically that is a C Lydian (C–D–E–F#–G–A–B) sound, but I think of it as G major (G–A–B–C–D–E–F#), with the harmonic emphasis on C. For the sustained notes in my melody/solo, I'm using a distortion pedal with the gain turned all the way up. I'm not using an EBow, but I will in a later example. I should also point out that my loop is only three measures long. This gives the piece a lopsided feel, making it difficult to know exactly where the first measure is. Such off-kilter equivocation is embraced in ambient music.

Ex. 4

One historical note: Eno has stated repeatedly that many people were creating music similar to his in the 1970s and before. Nonetheless, it was he who specifically labeled it ambient music and set some basic parameters for the genre, most notably in his liner notes for the 1978 album, Ambient 1: Music for Airports.

Contemporary Ambient Guitar Styles

By the 1980s, countless guitarists started exploring the realm of ambient music. I write "exploring" because, unlike other genres, many of the players most closely associated with ambient guitar also perform other styles. If you do your own investigation on such guitarists as David Torn, Steve Tibbetts, Michael Brook, or Daniel Lanois, you might be confused as to which recordings are considered ambient and which are more experimental in nature. Nonetheless, there are some key elements that the aforementioned players use to create contemporary ambient guitar music. Thus, for the following sections of this lesson, we'll focus more on fundamental techniques, effects, and approaches rather than specific player references. The following examples will also be a bit more guitar focused, rather than sounding like much of the enigmatic, non-guitar ambient music.

Swells of Reverb and Delay

One of the first techniques you need to master is using volume swells. One of the key sounds in ambient guitar music is avoiding the sound of the pick hitting the strings. You can achieve this "no attack" sound with your guitar's volume knob or a volume pedal. I prefer to use the volume knob—I find a Telecaster is perfect for this swelling effect—but not every guitar is laid out the same. Also, not all volume pots swell evenly, so depending on your instrument, you may need to invest in a volume pedal.

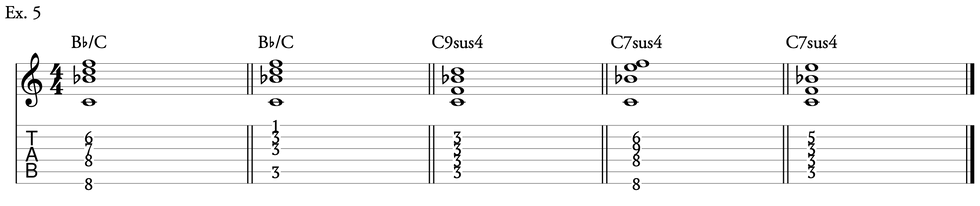

In Ex. 5, you'll hear the swelling of a Csus4 chord. The first two times are with the guitar's volume knob turned all the way down, followed by the volume knob being turned up with a smooth—and relatively quick—increase in volume. The subsequent two times are with a volume pedal. While the differences in execution are obvious, the sonic results are similar.

Ex. 5

Both these examples include a fair amount of reverb, which is arguably the most important detail to focus on when performing ambient guitar. Ambient music lives in a space, and whether that space is a gothic cathedral, a primeval cave, or digital cage, each serves to imbue the music with its own character based on the environment in which it's conceived.

The second effect you're going to want to experiment with is delay. Similar to reverb, delay enhances both space and character, with the added benefit of notes that can repeat (infinitely, if so desired), blossom, harmonize, inspire, and more, depending on your inclinations.

Ex. 6 is a slow, three-chord phrase that demonstrates the effect of both reverb and delay. The phrase is performed five times, first with no effects, then with three different reverbs, and finally with reverb and delay. Can you hear how each pass lends a distinctive character to the phrase? As with many sounds and tones, I'd suggest that none is better than the others, only different.

Ex. 6

I'll also point out that the chords here feature intervals known as seconds, both major and minor. Seconds have a distinctly dissonant sound—they long to be resolved, yet also seem content with their tension. This harmonic contradiction can be found throughout the ambient music genre. Since all but the third chord are missing the critical b3 (in this case, F), the "minor" labels I given them are implied by the overall phrase.

Modulation

To add color and movement to your ambient playing, add modulation or a combination of effects. For more on mixing and matching effects see my Feb. 2018 PG lesson "Eclectic Effecting 101: How to Use Stock Pedals to Unlock New Sounds."

Ex. 7 is a swelled D chord using drop-D tuning that is performed eight times. First with reverb only, then seven times with seven different effects in addition to reverb: chorus, phaser, flange, tremolo, vibrato, Uni-Vibe, and rotary.

Ex. 7

EBow

One piece of equipment that many ambient guitarists use is called the EBow. The name of this piece of hand-held gear comes from the fact that it can sustain a note on the guitar the way a bow can sustain a note on other string instruments, such as a violin. For ambient guitarists, one of its most practical uses is demonstrated in Ex. 8. You can maintain a note without decay and without excessive volume or distortion, and this allows you to concoct phrases that are difficult (if not impossible) to accomplish with normal picking techniques and a quiet amplifier.

Ex. 8

Glissando Guitar

One final, uncommon—yet rewarding—technique for ambient 6-string is known as glissando guitar. Daevid Allen of the band Gong (a band that's hard to label, but I'd describe as the perfect blend of Pink Floyd, Frank Zappa, and Dr. Seuss) developed this technique after seeing Pink Floyd guitarist Syd Barrett doing something similar in the 1960s.

Glissando guitar is generated by gently rubbing the strings of the guitar over the body (not the neck) with a piece of metal. I find a disengaged tremolo arm, aka whammy bar, works well. My effects are compression, distortion, chorus, and delay.

I've found that what your fretting hand does is not nearly as important as where your "metal-bar-rubbing-hand" is placed. Ex. 9 is an example of glissando guitar with my metal-bar-rubbing-hand hovering between the two pickups of a Telecaster, while playing a Gm7 chord with my fretting hand. Intriguingly, the pitch goes down as I move closer to the bridge pickup and gets higher as I move back toward the neck.

Ex. 9

Putting It All Together

Ex. 10 puts many of the previous elements to work in one complete, live-looping piece. I'll break it down bit by bit.

1) Produce a D drone loop, using a volume swell, drenched in reverb and delay, and with an additional panning auto-filter effect to create movement.

2) Overdub Dm and Am arpeggios with additional delay and Uni-Vibe effects.

3) Perform melody in D minor, with long, sustaining notes using the EBow.

Ex. 10

Once I recorded this lesson's final example, I realized I could readily compose another dozen, mixing and matching the assorted techniques and effects we've discussed, creating both radical and subtle alterations on what you've already heard and learned. This is because, as with any genre (the blues for instance), ambient music consists of a few basic ideas but offers endless variations to the imaginative guitarist. I hope you can take the information I've presented here and devise your own ambient music, guitar-centric or otherwise.

This article was updated on July 23, 2021.