From the 12-bar blues to a shuffle pattern to a IIm7–V7–I progression, many musical motifs get recycled and repurposed. It's accepted that these ideas are simply out there in the air for songwriters and composers to use, gratis, as musical building blocks from which to create new work. Right?

Maybe not. A few years ago, Led Zeppelin was sued for using one of these common motifs as the basis for "Stairway to Heaven." I was as surprised as anyone. I've been teaching this chromatically descending minor chord progression as an example of a compositional tool for years, citing a series of examples of its use in different situations. But sure enough, the band Spirit had decided to lay claim to the progression.

During the trial in 2016, Jimmy Page admitted that his song and Spirit's "Taurus," "are very similar because that chord sequence has been around forever." Back when Page wrote "Stairway" in 1971, he was surely well aware of what he was doing. This chord progression had really been making the rounds in pop culture.

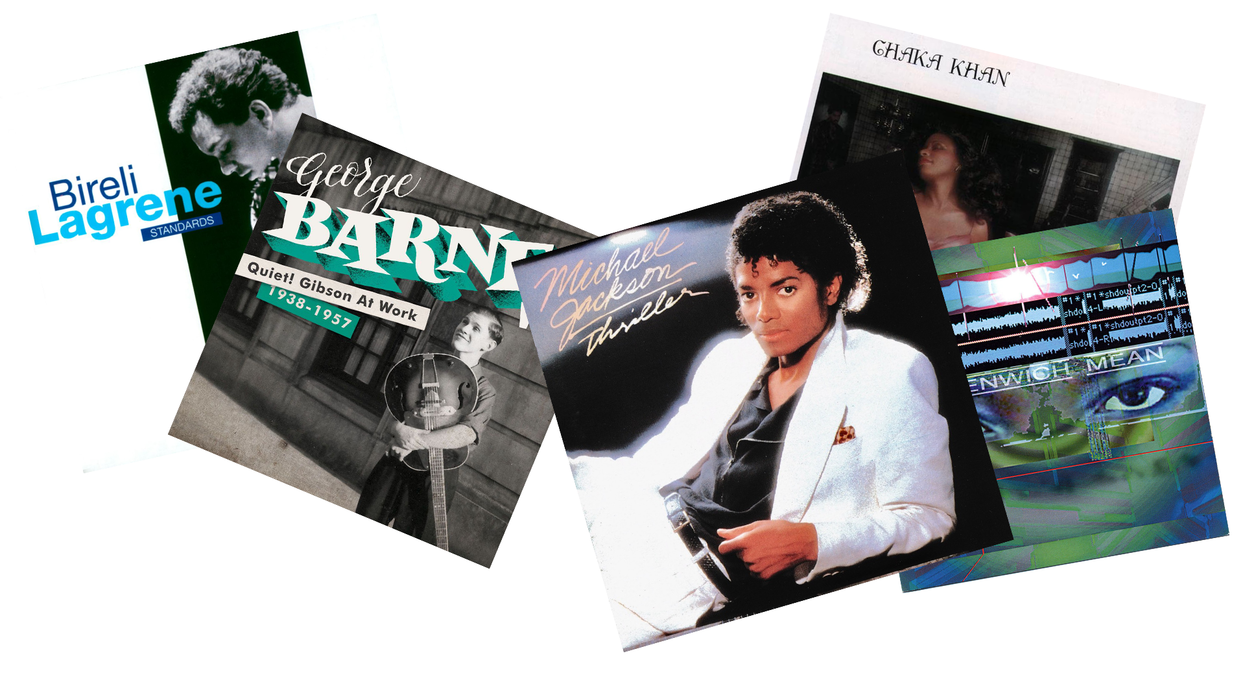

I've collected quite a few examples of this progression's usage to show what can be done with this motif, compositionally. These examples prove that this progression is nothing more than a kernel of musical information that songwriters and composers have been using for much longer than "Stairway to Heaven" or "Taurus" have been around.

The list below could be much longer, but I've edited it down to what I think are the strongest examples, where this motif is used in the most recognizable way, either as the beginning of a song or a section. So, you won't be seeing "You Are the Sunshine of My Life" by Stevie Wonder or the "Dead Man" theme by Neil Young, but just know that both of those songs are among the many that use this pattern.

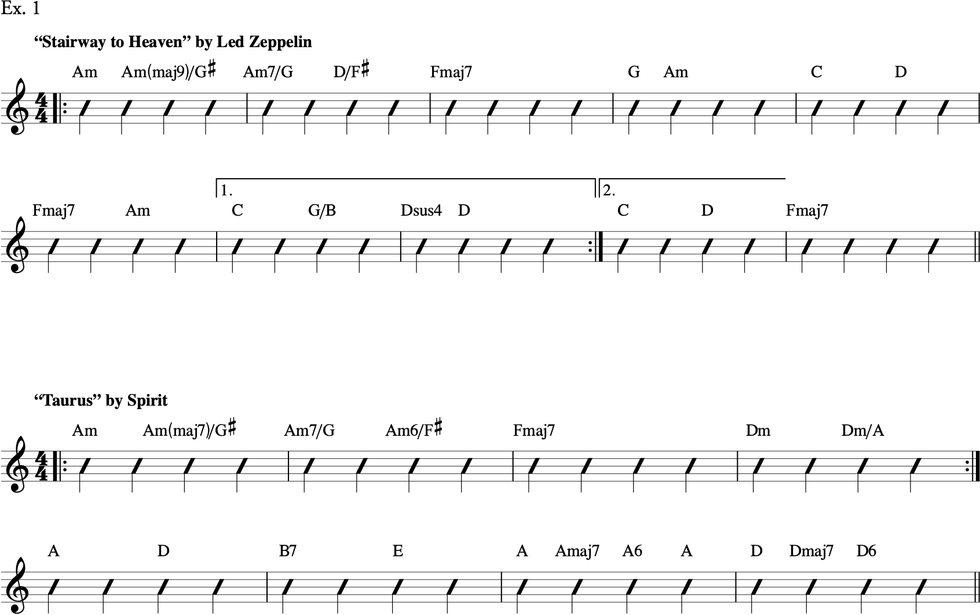

Because both "Stairway to Heaven" and "Taurus" are in A minor, I've decided to transpose all the examples into A minor to make it easy to compare them. But first, let's hear both "Stairway" and "Taurus."

Stairway to Heaven (Remaster)

Taurus

In Ex. 1, we see the opening phrases to both "Stairway to Heaven" and "Taurus." The first three measures are the only overlap in these phrases. Both songs have a descending bass note that starts on the root of Am, then descends chromatically to F. This bass line creates some interest in what could be a rather stagnant stretch of Am. The F# can be used as either an Am6/F# or a D/F#. Essentially, the difference between names here is based on what else happens harmonically around that chord and for our purposes, we can consider them to be the same chord.

Following the F# bass note, both songs have a measure of Fmaj7 and that's where the commonalities end. "Stairway" follows that with a resolution from G back to A minor, which would be a bVII resolving to a Im, while "Taurus" goes to Dm, which is the IVm chord.

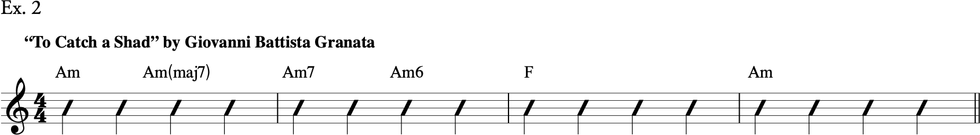

If we go way back in time to the 17th century, we find Italian Baroque composer and guitarist Giovanni Battista Granata featuring this motif in his "To Catch a Shad." In the trial, Led Zeppelin used this song as proof that the chord progression is in the public domain. Shown in Ex. 2, the song uses essentially the same progression as "Stairway to Heaven." "To Catch a Shad" was covered by the Modern Folk Quartet in 1963.

To Catch a Shad

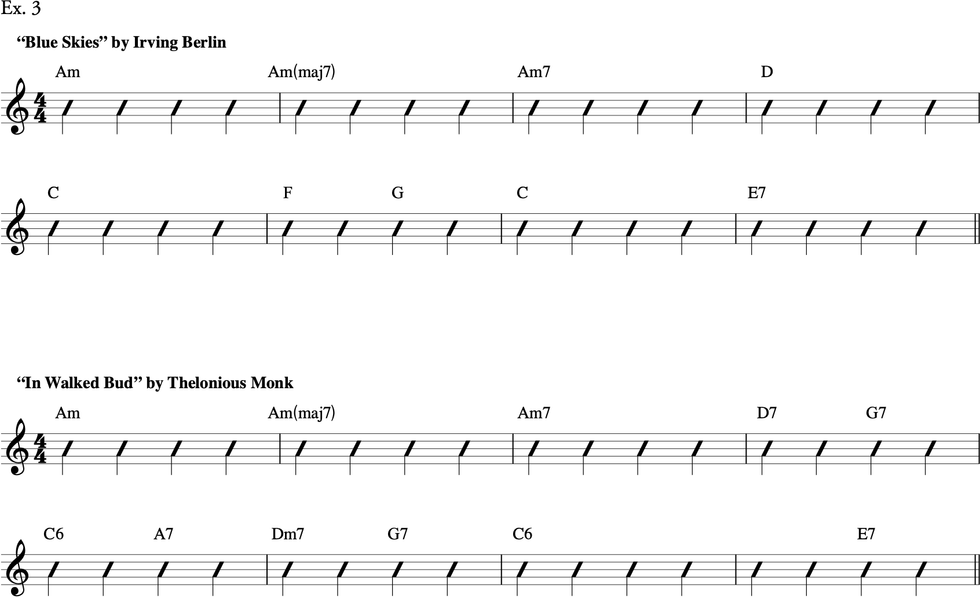

Fast forwarding to the 20th century, we discover that Irving Berlin used this same motif for the first four measures of his song "Blue Skies" in 1926, shown here in Ex. 3. The progression descends chromatically to a D major chord, then modulates to C major for the next phrase.

Thelonious Monk used "Blue Skies" as the basis for his song "In Walked Bud," first recorded in 1947. The first four measures are essentially the same, followed by a similar turnaround through a sequence of chords in the key of C major.

Irving Kaufman - Blue Skies (1927)

In Walked Bud

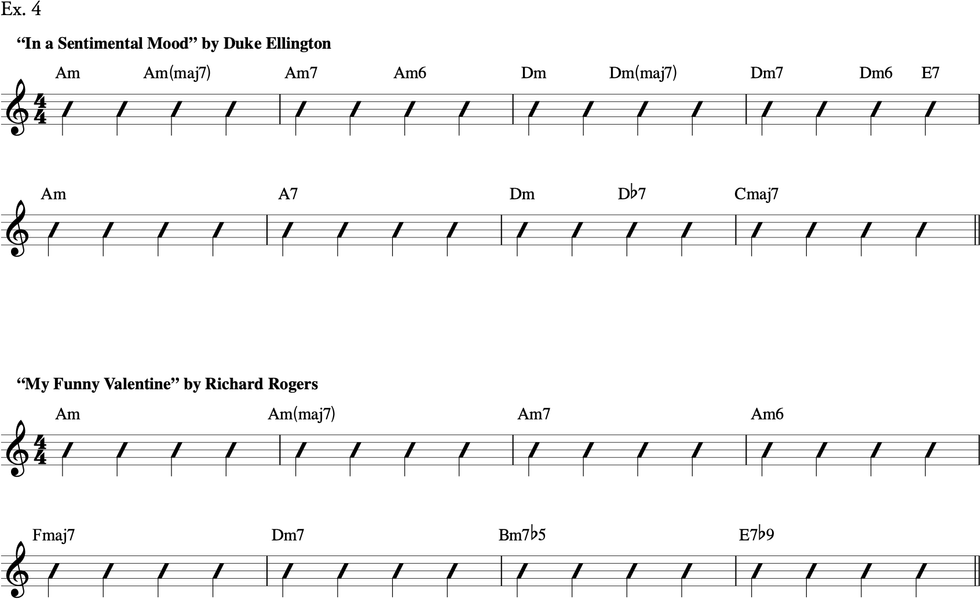

Both Duke Ellington and Richard Rodgers used this progression in the 1930s for their respective compositions "In a Sentimental Mood" and "My Funny Valentine." In Ex. 4, notice how Ellington used the progression, then repeats it up a fourth. The next phrase begins back on the Am chord and resolves to a C major.

Rodgers' "My Funny Valentine" follows the descending line down to F (much like Spirit would later do), and goes to Dm, before a IIm7b5–V7b9 turnaround back to the tonic.

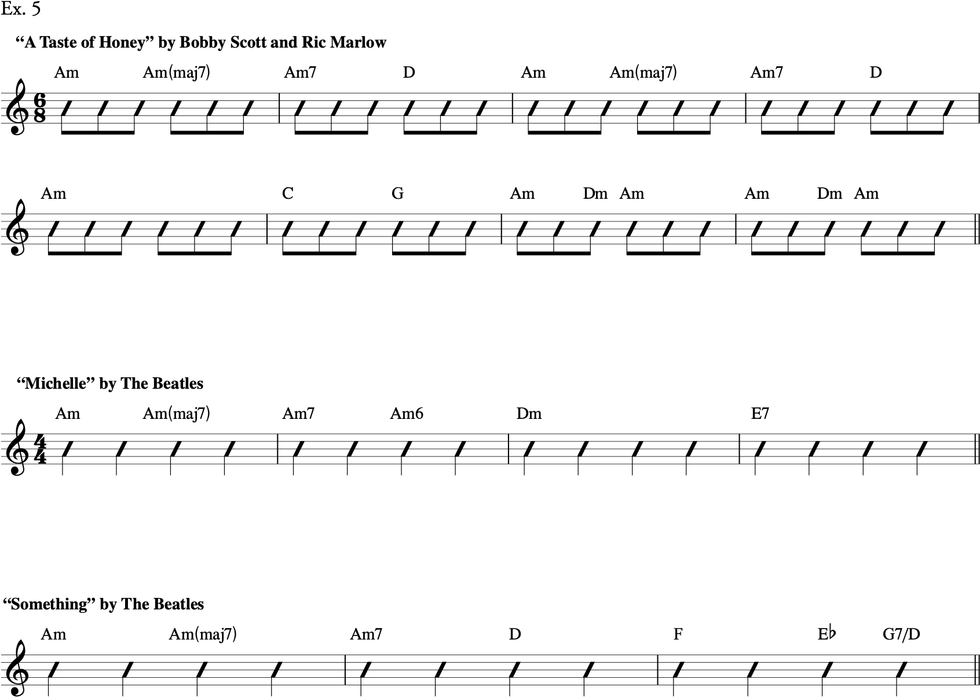

The Beatles never shied away from using a clever songwriting maneuver and our progression in this lesson is no exception—just check out Ex. 5. In 1963, they covered the song "A Taste of Honey" on their debut, Please Please Me. Composed in 1960 by Bobby Scott and Ric Marlow for the Broadway play of the same name, the song features a chromatically descending minor progression in the beginning of the verse.

This progression must have made its mark on the budding songwriters, because Paul McCartney and John Lennon wrote "Michelle" for 1965's Rubber Soul and used a two-measure descending minor progression as the intro, followed by a measure of IVm and V.

A few years later, George Harrison used the progression in "Something" from 1969's Abbey Road. This progression occurs in the verse when Harrison sings, "I don't want to leave her now," before coming back to the song's signature turnaround lick. An interesting thing about "Something" is that the verse opens with the same type of harmonic move on a C major chord. So, the first chords are C–Cmaj7–C7.

A Taste Of Honey (Remastered 2009)

Michelle (Remastered 2009)

Something (Remastered 2015)

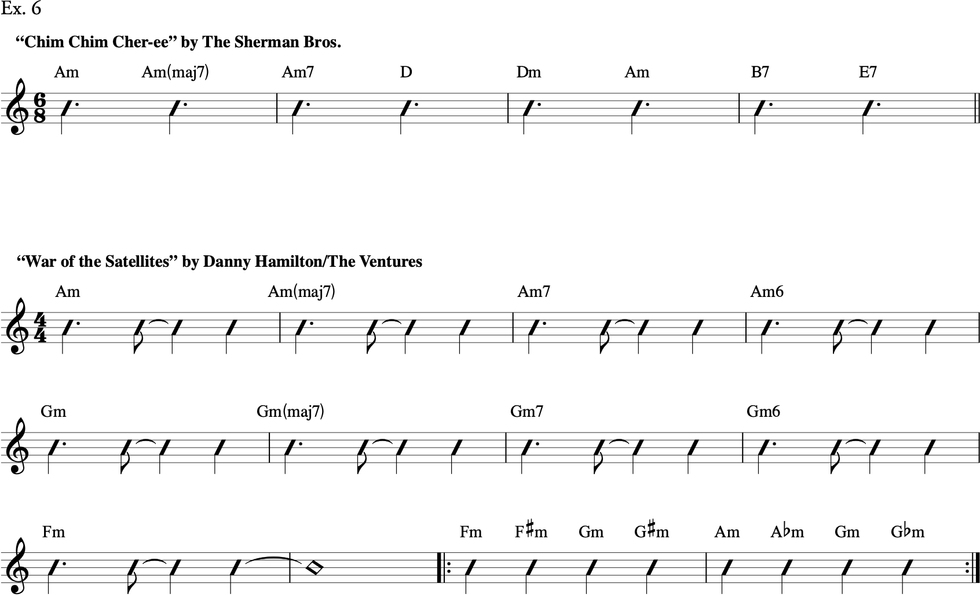

Ex. 6 shows the first phrase of the song "Chim Chim Cher-ee," written for the 1964 Disney film, Mary Poppins, by brothers Robert B. Sherman and Richard M. Sherman. Heavily covered by jazz artists in the mid '60s, this song was most certainly floating around in the popular consciousness. The first two measures are followed by a resolution (IVm–Im) and a turnaround (II7–V7).

Also from that same year was "War of the Satellites," written for the Ventures' In Space record by Danny Hamilton. In this surf rock classic, the descending minor progression is used in A minor, modulates down a whole-step and repeats in G minor, then modulates again to F minor, where it stays momentarily then jumps around chromatically, ascending and descending, before repeating.

Mary Poppins - Chim Chim Cher-ee

The Ventures War Of The Satellites (Stereo) (Super Sound)

Through these examples, we've looked at quite a wide variety of styles, from baroque music to Tin Pan Alley, jazz to surf, show tunes to classic rock. What's fascinating about all of these examples is the way the songwriters were able to take this common piece of harmonic information, put a unique spin on it, and go in different musical directions.

This article was updated on September 20, 2021