Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Intermediate

Lesson Overview:

• Create rhythmically interesting comping patterns.

• Learn how to use syncopation.

• Develop a more “conversational” approach to rhythm playing.

Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson's notation.

Wayne Krantz is probably another one of those guitarists whose name you’ve heard, but perhaps don’t know much about. It’s a great shame more people aren’t familiar with his playing, but when you create a unique voice on the instrument like Krantz has, you’re destined to be the wildcard in an established act or you have to carve out your own market, based around what you do.

A Berklee alumnus, Krantz is best known for his solo albums, and his brand of rhythmic jazz-fusion has earned him almost cult-like status (especially in New York City, where he regularly plays at the iconic 55 Bar in Greenwich Village). Outside of this, he gigs with the likes of Steely Dan, Billy Cobham, Jimmy Herring, and Leni Stern. To hear Krantz play some uptempo swing with Cobham, check out this video:

Although licks are a big part of many players vocabulary, sometimes the concept behind them is more important. Krantz is all about improvisation and I was fortunate enough to have some one-on-one time with him when he was in the U.K. a few years ago. This was one of the most profound meetings of my life, not because he showed me licks, but because his approach to practicing sunk in on a deep level and shaped my musical journey.

The first element of Krantz’ approach to playing is his incredible rhythmic phrasing. This can be explained using the “grid” concept. The basic idea is that when you put a click track or drum groove on to practice with, you have a couple of options: You could float over the beat the way Joe Satriani does with his legato lines. Or you can create complex sounds with non-standard subdivisions like quintuplets and septuplets. Alternatively, you can conform to the “grid” system I mentioned earlier, where each measure of 4/4 contains 16 note spaces and each of these is fair game for soloing.

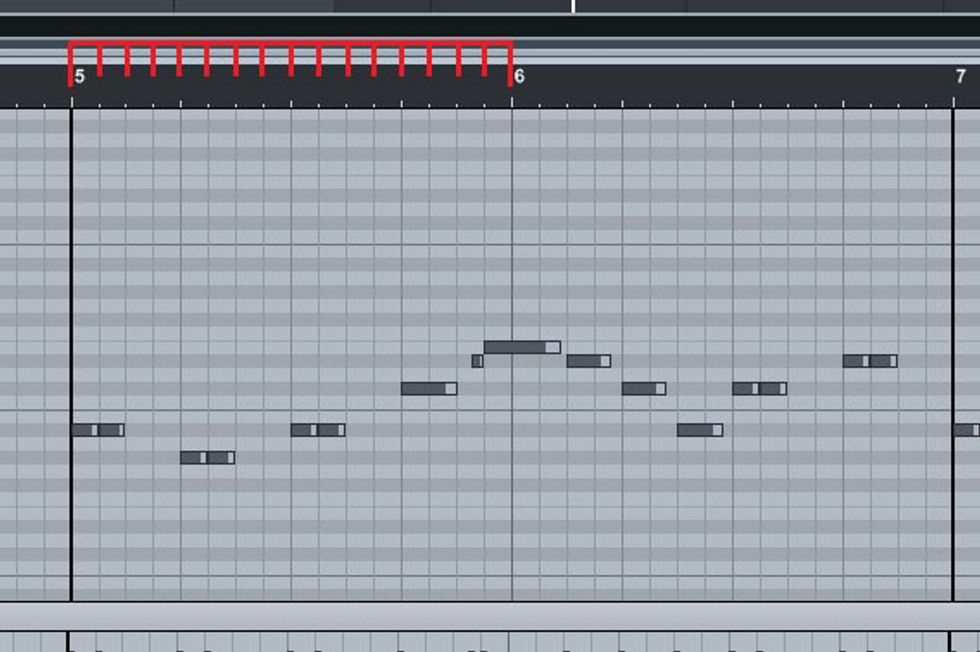

I like to think of it as the piano roll you work on when using MIDI in a digital audio workstation.

In the above image you can see a series of 16 little spaces per measure, which will give you a perfectly quantized (in time) sound when playing or programming. This sort of time feel is what gives Krantz an undeniable sense of groove when he plays—it just makes you want to tap your foot. You can always feel the pulse, even if he’s playing solo.

Obviously there’s a little more to this. If you just play quarter-notes in time, it’s not going to sound particularly groovy. What makes Krantz sound so funky is his constant use of syncopation, the way he accents the weaker beats.

In Ex. 1 we have a little riff similar to something Krantz might play. Before tackling it, notice how the rhythmic phrasing combines both on- and off-beat chord stabs and notes. In the first measure, the chord stab falls on the last 16th-note of the second beat, and the following three notes are all off the beat. The next chord stab is on beat 2’s last 16th-note, and the final chord stab gives us a little resolution by being on the beat.

Before talking about note choice though, it’s also worth noting that Krantz’ picking hand is quite advanced, and this allows him to use hybrid picking on chords to create a more piano-like attack. Also his alternate picking is so in sync with his internal clock that he doesn’t need to play the standard “downstroke on downbeats” to keep in time. Take this example slowly and over time build up speed while focusing on the rhythm.

The other element of his soloing that grabs your attention is the way he uses open strings. Just check out this live solo with Steely Dan!

Inserting open strings lets him get some really outside-sounding cluster voicings, and it’s something well worth exploring. The downside is that these voicings are obviously key specific, as you won’t be able to move them around due to the open string, but it’s not nearly as limiting as you might think.

In Ex. 2, I’ve composed a short four-measure idea using the notes of D Dorian (D-E-F-G-A-B-C). Notice the open strings in the chord voicings and lines, particularly the chord moving into the second measure, where I’m able to play root-2-4-5, having both the root and 2 (a tone apart), as well as the 4 and 5 (also a tone apart). It yields an unusually rich sound.

This knowledge of intervals is what makes Krantz really tick. If you want to get deep inside his mind, I’d recommend you check out his book An Improviser’s OS. The gist is that we can throw out everything we know about scales and instead just look at formulas. The major scale can be boiled down to its key information: 1-2-3-4-5-6-7, and the blues scale could just be thought of as 1-b3-4-b5-5-b7.

This seems like a huge jump when you already know your scales, but even if you take all the modes of the major scale, melodic and harmonic minor, diminished, whole-tone, and even harmonic major, you’re still only at 30 scales. Then, if you throw in the major and minor pentatonic and common arpeggios, you still only have 40 sounds at your disposal—at most.

Krantz will see any combination from some two-note group up to 10 or 11 notes as fair game. It sounds like a lot, and it is, but it opens you up to 2,048 different sounds. Now if you practice those without any bias, you’ll soon find that after learning 20, you can pick out any formula and practice it because you have a deep understanding of where every interval lives on the neck in relation to a given note.

Ex. 3 is a short improvisation using the formula 1-2-3-4-b5-5-6-b7 in the key of E. (You can also think of this as a Mixolydian scale with a b5.) Take note of all the elements we’ve talked about so far: the use of syncopation, close intervals (the last four notes in the third measure), and a couple of nice little chord stabs for punctuation.

Our final example (Ex. 4) attempts to dig a little deeper into Krantz’ approach to playing chords and improvising with chords. He’d think of this the same way he’d think about single-note improvisation.

In this example, we’re drawing from the Lydian mode (1-2-3-#4-5-6-7), another common modal setting that you might be required to jam on for a long time. We’re blending together chords stabs, melodic content, and rhythmic punctuation on the low strings. The idea that this can be improvised is beyond me, and the result is anything but predictable and always exciting to listen to.

One way to experiment with these voicings is to take a simple little shape, like a major triad, and shift the root up to the 9 or move the 5 down to the #11. Get creative and don’t just rely on what you’ve played thousands of times before. Take a few minutes to seek out one of the thousands of things you’ve probably never tried before.

This lesson really only serves as an introduction to Krantz’ style. When you’re done here, do your own listening, transcribing, and experimentation. And be sure to pick up some of Wayne’s stuff. One of my favorites is his 1993 release, Long to Be Loose.