Just like anything that is important to you, you need to have a plan in place to accomplish it. Last month, I had to learn approximately 60 songs in the span of less than three weeks for a three-part livestream series. It wasn't a situation where it would be appropriate for me to read charts off a music stand. I had to make a practice plan with my family in order to have the time and resources I would need to execute this rather monumental task. I want to take you step-by-step through my strategy for tackling those tunes. Hopefully you can find tips to help refine your approach—even if you don't have a newborn.

What if you don't have something pressing to force you into laser-focusing your practice habits? How do you manage your time without a deadline to hold you accountable?

If you're reading this article, you're a self-motivated person who wants to improve. Excellent. Give yourself goals that are achievable and quantifiable to stay motivated and track your progress. Rather than a goal like “Get better at soloing" select something like “Transcribe solo on [name a specific song]" as your first weekly goal. Then, build upon those goals by using that material to achieve another objective. Small steps add up to big changes and give you the focus you need to establish good practice habits.

Preproduction

Using this soloing goal as an example, find ways to practice outside of the practice room so you can maximize time with your instrument. If you're trying to cop a solo, learn it by heart before you sit down to play it. Sing along with it over and over again to the point where you can sing it without the recording. Here's an exercise to try: Record yourself playing the chord changes and then sing melodic ideas over it. You can do so much work in advance of heading to the woodshed. And if you're a busy person, preproduction is the key to success.

Lightning Round!

Turn off notifications on your phone. When you have precious little time, an errant tweet notification can derail the 30 minutes you have set aside. Jason Isbell has been responsible for nearly as much social media worm-holing as he has musical inspiration for me. Dude's a Twitter genius. You've been warned.

Organize your practice space. You don't want to be searching for stuff when you're under the gun. I have notebooks, Sharpies, pens, and pencils at the ready along with headphones and adaptors. Take this tip from Rachel Hoffman's home organization masterwork Unf*ck Your Habitat: “A Place for Everything and Everything in Its Place." If you have a place for everything, you're never looking for your stuff. And you also don't leave crap everywhere, thereby potentially annoying other people you need as allies.

Maximize good brain time. Is there a time of day that's better for your unique brain function to practice? Take advantage if you can! I'm a night owl so practicing after the baby is asleep works well for me, thankfully.

Sing! You can save yourself hours of time by singing along with parts you're trying to learn outside of your practice space. Do it while driving, while doing the dishes, while exercising, any opportunity you have to listen to music. This is how I learn all bass lines. If you can sing it, you can play it. When you sit down to learn it, you'll know it in your bones—literally. You will immediately hear when you make a mistake and be able to find the note you're looking for by singing the pitch you know you're supposed to hear. It's remarkable how well it works, especially for the students who say “But I can't sing!"

Do a little each day. Like exercise, a healthy diet, and meditation, practicing a smaller amount each day is more beneficial than one big cram session every now and then. Productivity timer cubes are super helpful as a means stay focused for small blocks of time. Even 15 highly concentrated minutes a day will pay dividends and create consistency in your practice and playing.

Take lessons. A teacher is a great way to stay accountable on your musical journey. An objective third party taking inventory of areas where you could improve and giving you homework is a surefire way to ensure you spend time with your instrument each week. Can't afford a ton of lessons? Make a commitment to learn a new technique by watching videos on the subject or treat yourself to a one-time or monthly evaluation by a musician you admire and have them map out some goals for you.

Include your loved ones. When something's important to you, you should share it and celebrate it with your loved ones. Music is the ultimate tool for shared celebration and finding ways to include your people in your practice endears them to your commitment, rather than viewing it as something that takes away from your time together.

My students always amaze me with how they get loved ones on board with their musical pursuits. One student's girlfriend loves karaoke, so he has committed to learning to play and sing a song for karaoke nights. She's excited for him to practice, knowing that they will spend special time together because of it. Another student has his wife help with interval training, playing intervals on the piano so he can guess what he's hearing. His wife loves to tease him about it, and they have a blast with it. Several of my students ask their friends and family what songs they'd like to hear. It's great fodder for learning new material and it gets the people you care about to be invested on a whole new level. And that rocks.

Now I'll consolidate all the info above into a real-world situation and share my practice plan for that 60-song, three-part livestream I mentioned…

Preproduction

I had to do as much prep work ahead of time as possible so I could capitalize on the time I would have to leave my baby with another willing and helpful adult. There are several steps I always take before I sit down to practice new songs. Here are the highlights:

Organize the Music and Listen

Listen to the music you're working on as much as possible. I listen while driving, pushing the baby in her stroller, in headphones next to her while she's napping, etc… Consolidate songs into a playlist in a medium that's easy to access while driving so you're not fumbling with your phone. You don't want some stuff in Dropbox, some stuff on YouTube, and some stuff in Spotify. Organizing your material upfront will save you lots of time later on.

Write Charts

I wrote my charts largely in the car in parking lots while running errands and while the baby was napping. (I write charts by ear and you can too! See my article on The Nashville Number System for more tips.) You can also ask for charts from fellow musicians on the gig (tactfully, please, and return the favor when someone asks you) or source them online if it's a cover gig.

Practice in Your Head

I know myself well enough to recognize when I truly know a song. I can visualize my hands on the fretboard while listening to it and if I get to a spot where the image doesn't come quickly, I know it'll need some attention. I then listen through the songs while reading the charts I wrote in those Nashville parking lots and highlight the trouble spots and anything else that surfaces as questionable.

Get the Setlist

If possible, get the setlist in advance. Then grab a couple pieces of hardy card stock paper and two different colored Sharpies. Write the songs in order in alternating, high contrast colors. This way your eye can find your notes quickly on the floor.

Now to execute a practice plan and juggle a small human…

I had 60 songs to learn that were divided over three 90-minute sets of roughly 20 songs each with about a week between each performance.

I focused on the shows in chronological order and spent all my time listening to those 20 songs, over and over for three or four days before touching an instrument.

My practice time was divided into two 90-minute sessions per day over the course of the two days before each show. One was in the morning when someone could watch the baby and one in the evening after she was asleep.

First Day Practice Sessions

I split the setlist in half and tackled 10 songs at the morning session and the remaining 10 at the evening session. Ninety minutes is about what I need to run 10 songs I've never played (but on which I have done proper preproduction). Some songs I'll only need to run once to get them under my hands, some might need a couple of run-throughs.

I play through each song, focusing on trouble spots, running those sections a few times.

I notate (usually with a highlighter or an asterisk) any trouble spots on my chart I didn't catch during the critical listening and charting pre-practice phase.

Second Day Practice Sessions

I redo the same approach, only this time I try not to look at my charts. As I play along, I take note when I find myself asking “How does that bridge go?" or “Am I in at the top of the song?" I write those notes down in Sharpie next to the song title on my setlist.

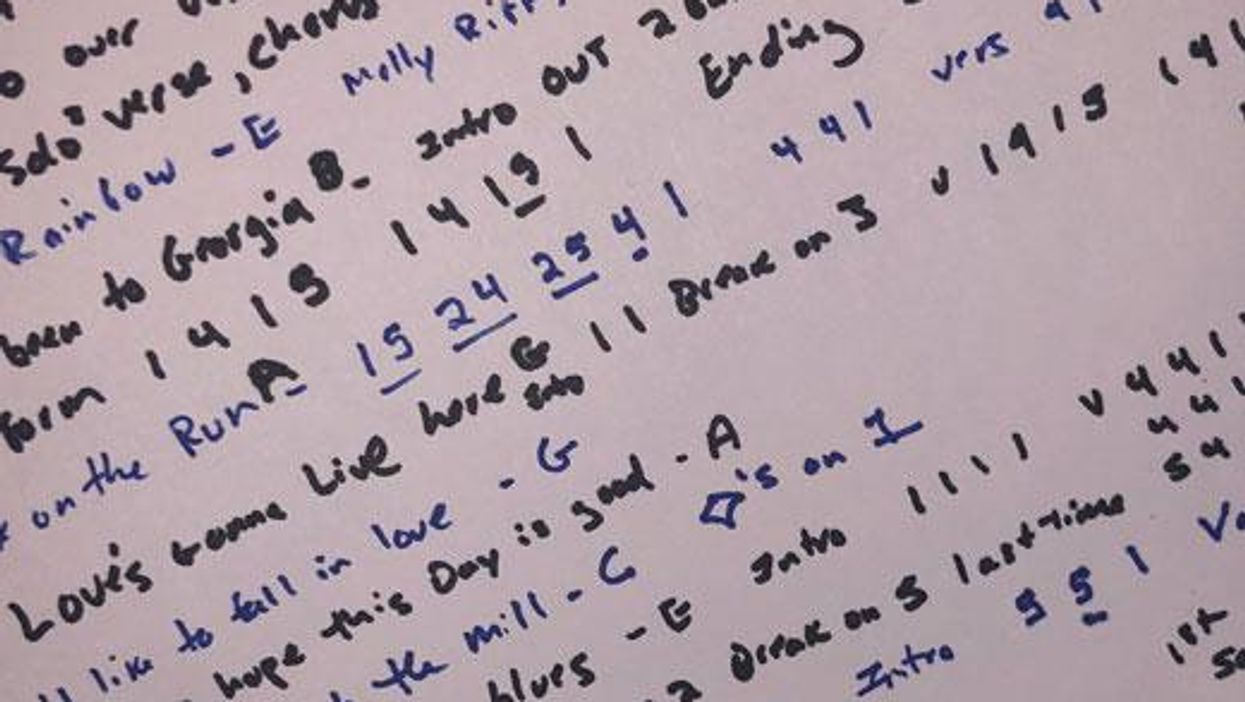

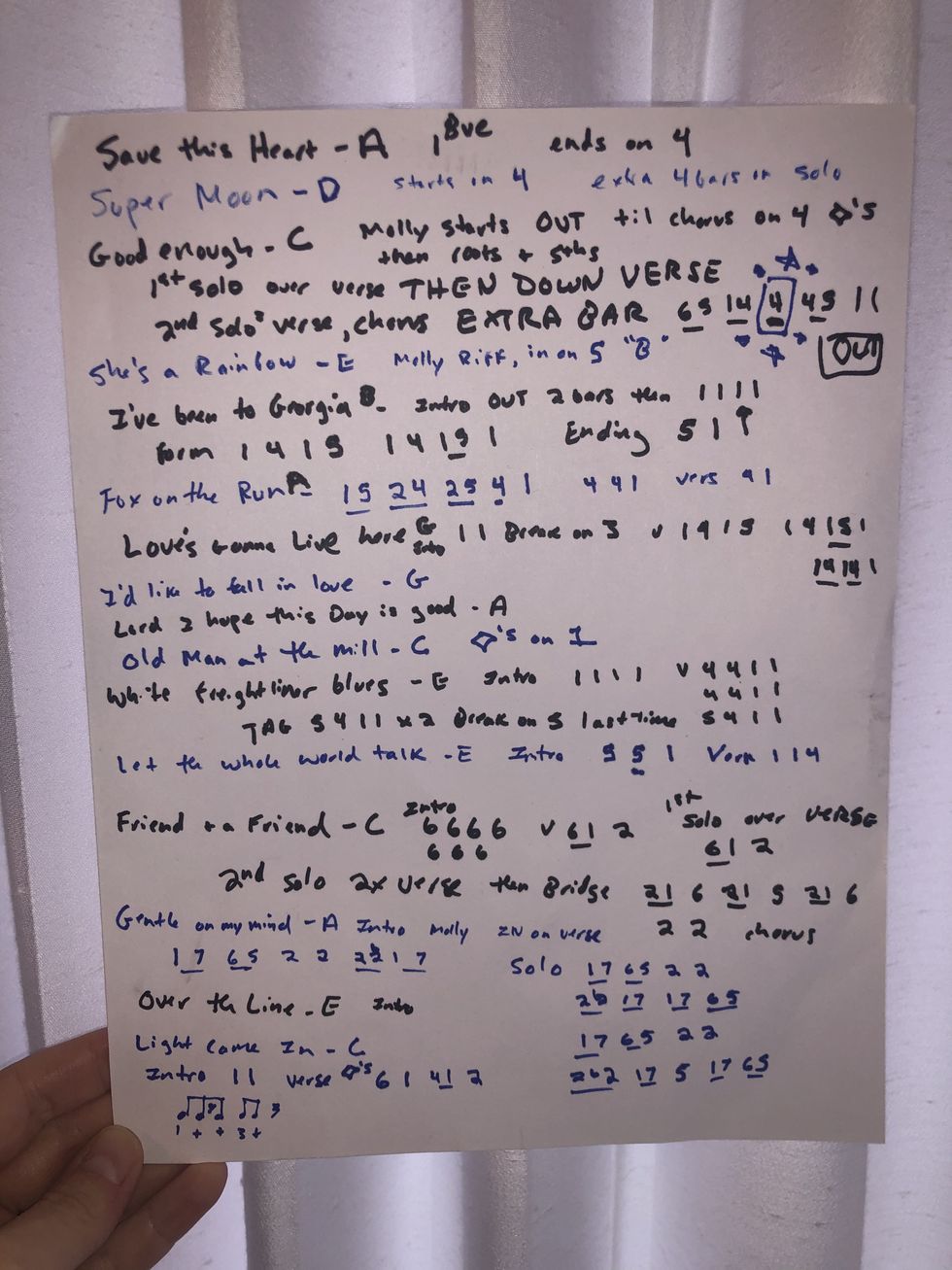

And now I present my setlist for the final livestream, which ended up being 16 songs in length. This is written using the Nashville Number System and is a peek into my process. Thanks to my husband and mother-in-law for working with me to make my practice time a reality and best of luck to all of you busy folks out there looking to get the most out of your precious time.

To quote the author Harvey Mackay:

Time is free, but it's priceless. You can't own it, but you can use it.

You can't keep it, but you can spend it. Once you've lost it, you can

never get it back.

Make the most of it, friends!