Sad songs make me happy like drinking makes me thirsty. It’s a strange paradox most of us share; nobody enjoys being sad in real life, but boy do we love to listen to a song that makes us miserable. It’s magic, or maybe a better word is “alchemy”: If you take a few inert ingredients (one C major scale, one D#, a 3/8 time signature), then arrange the ingredients in the right order, like Beethoven had in mind, and play dynamically with a flowing tempo that breathes a bit, the final product can tear your heart out.

Für Elise starts with this motif in A minor, full of longing and melancholy, then lifts with the contrast of the C major—creating a sense of whimsy, unpredictability, and playfulness. Then it goes back to the legato A minor, which now sounds even sadder by comparison to the happy, whimsical relative major.

“Although writing music was his livelihood, he wrote this as therapy, or a private declaration of love and loss.”

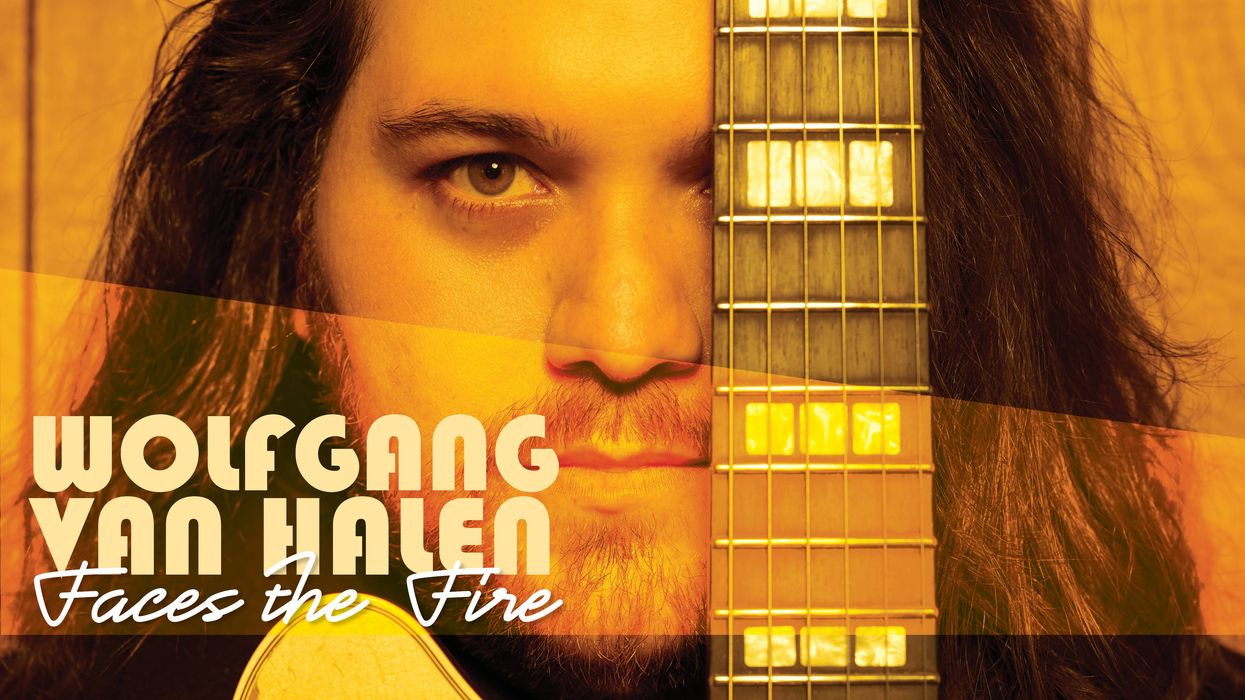

I recently worked up a guitar arrangement of Für Elise and played a version while filming a PG video of the Godin Multiac Mundial. It’s an embarrassingly rough, semi-improvised performance, but what I wanted was to take this epically sad melody and play with it, adding some fun jazzy/bluesy American improvisation to put a wry, crooked smile on the tragedy. That’s part of the magic of this piece; it’s a simple melody that can be musically reinterpreted as blues, ragtime, anything. Even Nas used a sample of it in his song “I Can.”

After filming the Godin video, I said to my colleague Chris Kies: “I don’t know who Elise was, but boy did she do a number on Beethoven.” The always well-informed Kies told me that Für Elise was discovered 40 years after Beethoven’s death. Beethoven had never published it, and the only clue to the song’s inspiration were the words “Für Elise” messily scribbled on the top of the forgotten page. There were apparently three Elises in Beethoven’s life, so no one alive knows for sure, but what it comes down to is Beethoven fell in love, it did not go his way, and he dealt with it by writing this music. Although writing music was his livelihood, he wrote this as therapy, or a private declaration of love and loss. Perhaps it was so soul-crushing that he did not go public with the music. We turn to music when words fail, right?

Hearing the rest of the story made the whole thing even sadder to me, which led to my spontaneously breaking into tears, thereby turning a normal product video into an awkward workday for me and the very tolerant Chris Kies.

Weird, right? I never want to cry, particularly in front of people. It’s horribly embarrassing to be that vulnerable in public. I’d rather be seen going to the bathroom in public than crying, and yet I’m drawn to sad songs like a moth to a flame. I’ve broken into tears while performing and turned my back on the audience or buried my head in my pedal steel until I could take some deep breaths and pull it together. So why do we voluntarily submit ourselves to this kind of torture?

There may be some science that helps us understand it. One study suggests that music, particularly sad music, stimulates the release of comforting hormones like prolactin. There was a study where scientists played sad music for people and then measured their prolactin levels and, as you guessed, listeners who felt some positive effects from the sad music had just released a heavy hit of prolactin. Other listeners who report feeling sad without the accompanying positive effect, as it turns out, already had a higher level of prolactin to begin with, “suggestive of a homeostatic function.” It seems our bodies are using music to self-regulate our chemical balance. If you need a boost of prolactin, music will give it to you. If you don’t need it, it saves it for later. Another study suggests that sad music can also stimulate that feel-good bringer of pleasure and rewards, dopamine. In short, listening to sad music can flood your body with happy chemicals.

Maybe another reason we willingly subject ourselves to the beautiful sadness of melancholy music is to engage in a fictional sadness to help deal with that vague malaise that we all carry around but never unpack. A lifetime of quiet heartbreak that we don’t even understand and try not to think about. Music releases the steam valve before the boiler blows.

But the more I looked into the appeal of sad music, it seemed to ask more questions than answers. Like, why do we connect to the songs we connect with? Does it remind us of someone? Is it empathy? Is it self-pity? Do we connect with the artist? And perhaps the most puzzling bit of it all: Why does flattening a 3rd, 6th, and 7th in a scale make a melody universally sadder? That’s the magic, the mystery, the therapy.