A lot has been made of the fact that a large portion of early hip-hop was based on “taking” pre-existing songs and recordings, created decades before, and presenting them in a new, different light. This process was known as sampling, named for the sampler, which could literally record chunks of time as digital audio and allow users to manipulate it at will via keyboards or drum pads.

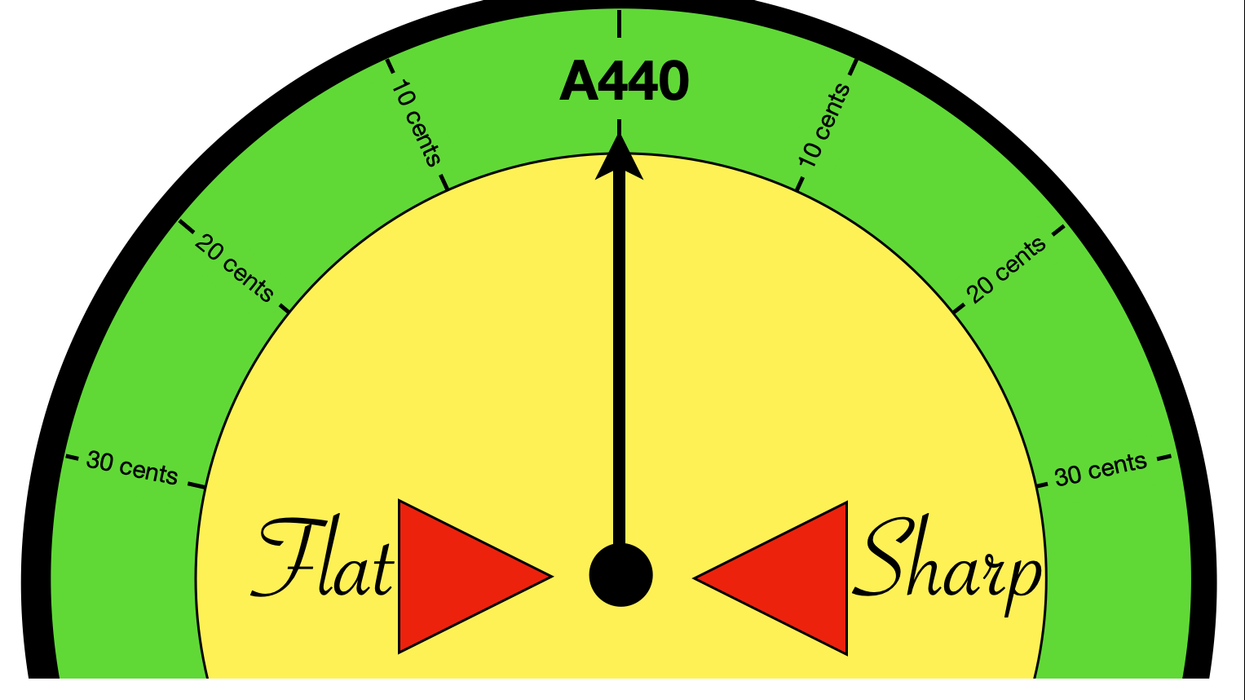

The best examples of these machines, which included the Akai MPC60 and Ensoniq ASR-10, allowed users to change the pitch, reverse, chop into pieces, sequence, alter dynamics, and much more. Aside from the technology that made all this possible, the intended usage, as defined by the designers, was not all that different to earlier instruments like the Mellotron. However, what hip-hop producers did with sampling technology and all those extra parameters, was wholly different.

Depending on who one asks, the age of sampling confirmed that hip-hop’s early producers were either truly lazy or geniuses. The lazy part is the most obvious and unimaginative take—they didn’t create the music they sampled, and in many cases, didn’t credit the original composer. The genius part requires a little more open-mindedness and understanding of what was actually occurring, both from a musical and cultural perspective.

Some have argued that, aside from playing traditional instruments at a very high level, there was actually very little difference between what hip-hop producers did and what jazz musicians had been doing for many decades before. Just like hip-hop producers, jazz musicians took existing music, created for one purpose, and manipulated it, transforming it into their vehicle, for another.

In the beginning, this transformation was mostly stylistic/rhythmic, leaving the original song clearly discernible to the listener. But by the time we get to John Coltrane, we were observing jazz musicians who improvised over earlier songs by other composers, which had been transformed to the point of being unrecognizable, even to the most sophisticated of ears. Take, for example, Coltrane’s “Fifth House” (1961), which was actually based on “What Is This Thing Called Love,” a well-known Cole Porter composition written for the 1929 musical Wake Up and Dream.

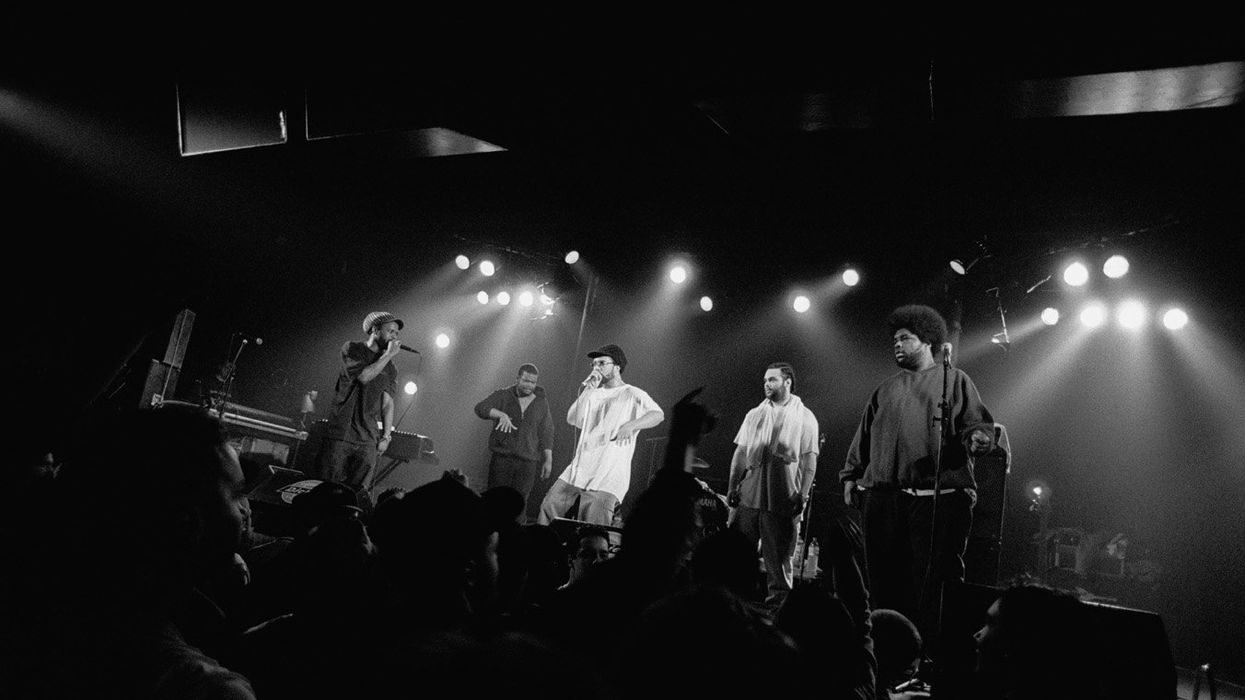

In the case of hip-hop, the goal was to create interesting vehicles for emcees to rap over. One of the earliest examples was “Rapper’s Delight” (1979), where the Sugarhill Gang literally looped an entire instrumental section of Chic’s “Good Times” (1979), transforming it into the perfect vehicle for 14 minutes and 37 seconds of nonstop rapping. Later on, hip-hop producers such as J Dilla contorted the samples used in their productions to the point where, even to this day, fans still argue over exactly where they came from. The most creative hip-hop producers have drawn from far and disparate sources to find the samples they use in their productions.“Hip-hop producers such as J Dilla contorted the samples used in their productions to the point where, even to this day, fans still argue over exactly where they came from.”

In my opinion, it cannot be refuted that both jazz and hip-hop musicians mastered this process by constantly pushing the envelope. All the while, they constantly used pre-existing art and transformed it to serve a completely different purpose, in aid of a completely different artistic statement. Theirs was a process of re-contextualization and this was central to both musics. Neither jazz nor hip-hop musicians were interested in simply “covering” popular songs, which audiences at the time already loved, in the way that a wedding band might. To go further, many of their transformations were so extreme that it would’ve probably just been easier for them to create completely new compositions. Many of them certainly possessed the ability to do so. So, why did they sample? I would argue that recontextualizing is not unique to literature, jazz, or even hip-hop. It is a fundamental technique employed by artists within many disciplines, and most likely has been for millennia.

The saying “There is nothing new under the sun” is apt. In reality, the actual nature of music is such that everything is based on something earlier. There are precious few artists who have actually created anything which could be considered completely new, and this is even more so the case post the establishment of the modern music industry. How many songs use exactly the same progression, or melody, or arrangements, or drum patterns, or bass lines? This is before we even consider lyrical content! There’s a reason why plagiarism within music is confined to a very narrow set of circumstances. Covering, reinterpreting, or recontextualizing earlier music is what most musicians have done for the vast majority of history.

Like jazz before it, hip-hop provided new leases on life for many long-forgotten songs. That also came with the additional benefit of more profit for publishers, but ironically, in the end, it was publishing that killed sampling. It just became too expensive, with some publishers asking so much for sample clearances that there was nothing left for anybody else. At first, producers tried to “recreate” samples with slight changes to get around this, but a few lawsuits later, it became clear that using samples was over.