I’ve preached the gospel of playing gigs before—and how they can lead to all kinds of benefits, from honing your chops to making new connections to unexpected adventures. Here’s an example.

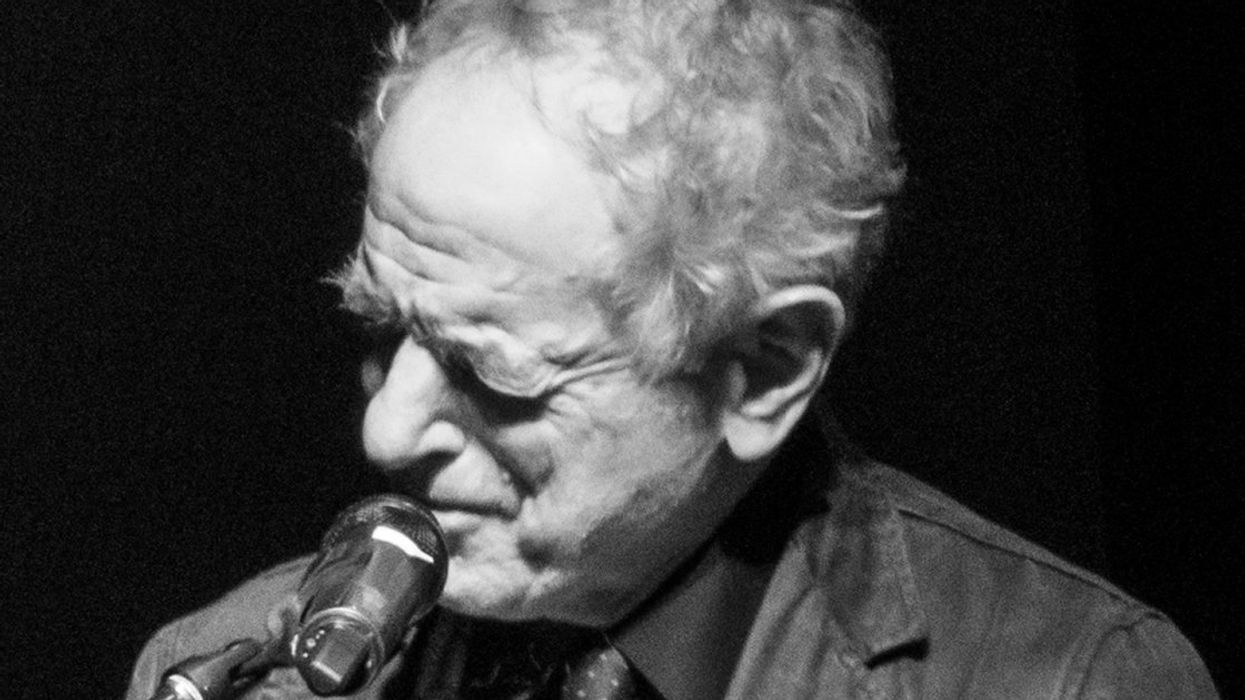

Starting in 1999 and for the next several years, I served as bandleader for the counterculture icon, political activist, musicologist, and poet John Sinclair’s Northeastern tours, essentially working dates in New England and New York City. Sinclair, who turned 81 last year, is a heavyweight in narrative poetry, although he is best known as the manager of the MC5, a founder of the White Panther party, and the subject of John Lennon’s song “John Sinclair,” written after police persecution of Sinclair for his activism led to his arrest and nearly three years of imprisonment for handing two joints to an undercover police officer.

There was never a dull moment on the road with John. First, there was his marvelous wit and perspective, and his storytelling, to keep things lively in the van. And at performances, I met former Black and White Panthers, ex-Weather Underground members, other poets and writers, and, in general, a cast of fascinating characters. I was paid in weed for a concert by a promoter for the first—and only—time. We played with Thurston Moore at Manhattan’s Nuyorican Poets Cafe, and at historic British rock impresario Giorgio Gomelsky’s downtown loft.

Although John was a bit frail, having endured two serious knee surgeries and leading the kind of lifestyle that doesn’t typically allow humans to reach his current age, every time he took the stage I was inspired. I might have needed to help him get off his chair before a show, but the moment the music started, he’d rise up on the balls of his feet and start his verbal alchemy, keeping the audience—and the band—under his spell for one or two hours as his voice uttered phrases with the free-flying efficacy of John Coltrane’s horn.“For a moment, I went slack-jawed and stopped playing. I felt a rare, transcendent awe. And I’m not indulging in hyperbole.”

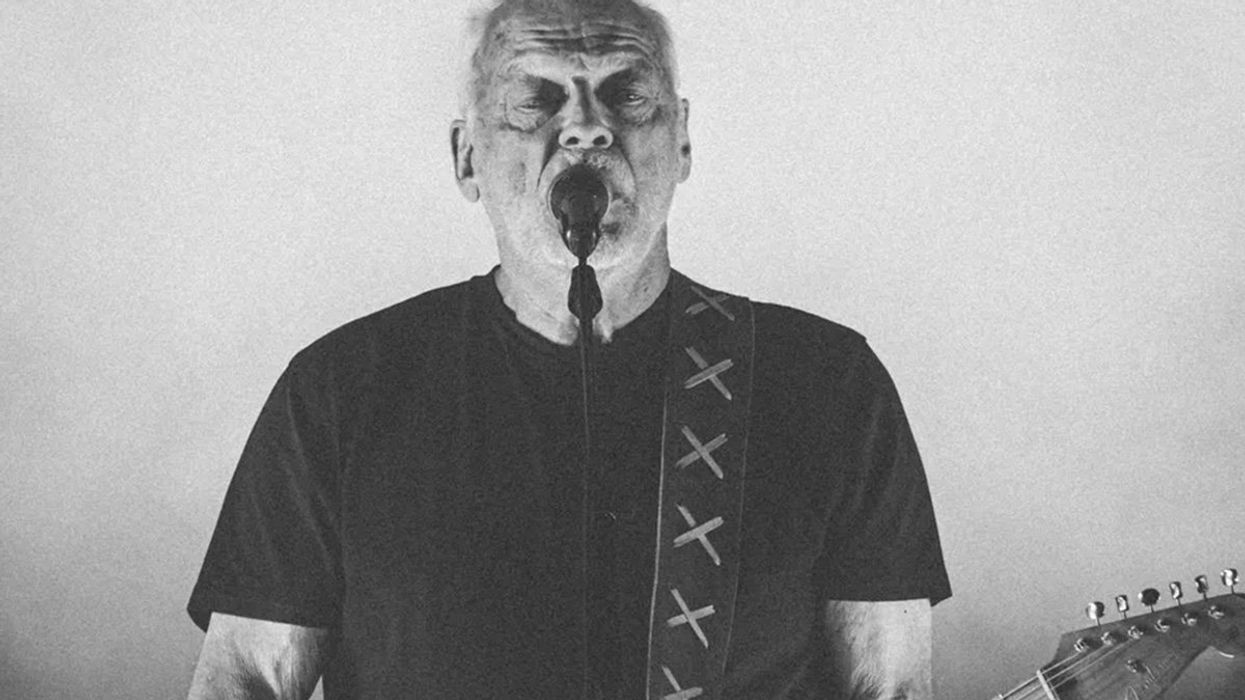

One night, we were playing the Kerouac Festival in Lowell, Massachusetts, Kerouac’s birthplace, with a four-piece that included fellow guitarist and friend Mark Sullivan, who taught me a great deal about tone and improvisation. During the set break at the colorful Worthen House Cafe, where Kerouac and Poe had been regulars, John introduced me to a professorial-looking fellow in a jacket and sweater, sitting in front. It was composer and multi-instrumentalist David Amram. Only later did I learn that he was a legend in American music who’d worked with Aaron Copeland, Thelonious Monk, Bob Dylan, Wynton Marsalis, and enough other heavyweights to fill this page. In 1957, he also staged one of the first poetry readings with jazz accompaniment, with Kerouac. David asked if it was okay to sit in. I said, “Of course,” and asked him when he’d like to come up and what he intended to play. He told me he’d let me know.

About 20 minutes later, when Mark and I were creating a sonic firestorm toward the end of John’s “Fat Boy,” about the bomb that detonated over Nagasaki in 1945, David gave me the nod. At the time, I had my foot up on my Twin supporting my Strat as I rode feedback with its whammy bar, and Mark was shredding like a maniac over loops, and David still had no instrument as he approached the microphone.

I was perplexed … until David reached both his arms across his chest into his jacket—like a pistolero—and pulled out a pair of pennywhistles, put them both to his lips, and entirely destroyed everything. Imagine Coltrane on a pennywhistle, imagine a steam locomotive screaming through a reverberating valley, imagine every rage and delight compressed into one incendiary melody that spoke in all human tongues at once. For a moment, I went slack-jawed and stopped playing. I felt a rare, transcendent awe. And I’m not indulging in hyperbole. Recalling it now, I have goosebumps and my eyes are nearly tearing. It was untamed and profound.

I don’t know how long David played, but Mark and I laid down a blistering pad for him, and he sailed over it like an Icarus that refused to fall. And when he’d expressed what he wanted to, he put the pennywhistles back in his jacket pockets, turned around and smiled, nodded, and returned to his seat.

In those minutes, I learned a zillion things, but principally to never be dismissive about any instrument, to leave myself open to all musical experiences, and to embrace the unexpected with all my heart. Sometimes I fail to maintain those lessons, but I try.

I’m not guaranteeing that playing gigs will provide you with experiences like that one. But if you do it enough, and fall in with the right artists, they just might. The next step is yours.