The background of Elk Guitars is as intriguing as its oddball models, which are now rarities on the vintage market.

Okay, so what if I told you that the intersection of a love for country music, a hunter’s magazine, and a dentist led to the start of one of the legendary Japanese guitar lines of the 1960s and ’70s? Well, read on good people, and let me spin the yarn of Elk Guitars!

“He liked the simple name and realized that the word ‘elk,’ written in English or Japanese, is only three characters. And so, the ‘Elk’ brand was born.”

Started in 1963 by Yukiho Yamada, the company was originally called Miyuki Industries and focused on the production of electric guitar amps. Yamada was a fine guitar player and was fiddling around with amp designs for his own onstage use. The company gained a solid reputation by making 35- and 45-watt amps using the “Echo” brand name. Then, around July 1965, they started making electric guitars, which coincided with the electric guitar boom and the Beatles creating musical shockwaves around the world.

Yamada had a passion for Western-style music, and had an older brother who would play records for him like “Oh My Darling, Clementine” and the theme from Stagecoach. He also grew up during American occupation and was influenced by music played on the Far East Network radio station, or FEN. His taste for country music matched his love for the outdoors and the idea of hunting, and, while perusing a foreign hunting magazine, he came across a photo of an elk. He liked the simple name and realized that the word “elk,” written in English or Japanese, is only three characters. And so, the “Elk” brand was born.

Yamada was adamant from the start that his guitars be of professional quality, and he researched everything from tonewoods to pickup designs to truss rods. Before he started electric guitar production in earnest, Yamada bought a Fender Jaguar, which was a very expensive purchase in Japan at that time. His aforementioned older brother happened to be a dentist, and, using X-rays, he helped study the truss rod and other components of the Jaguar without having to destroy it (as was done to a few Mosrite guitars at that time).

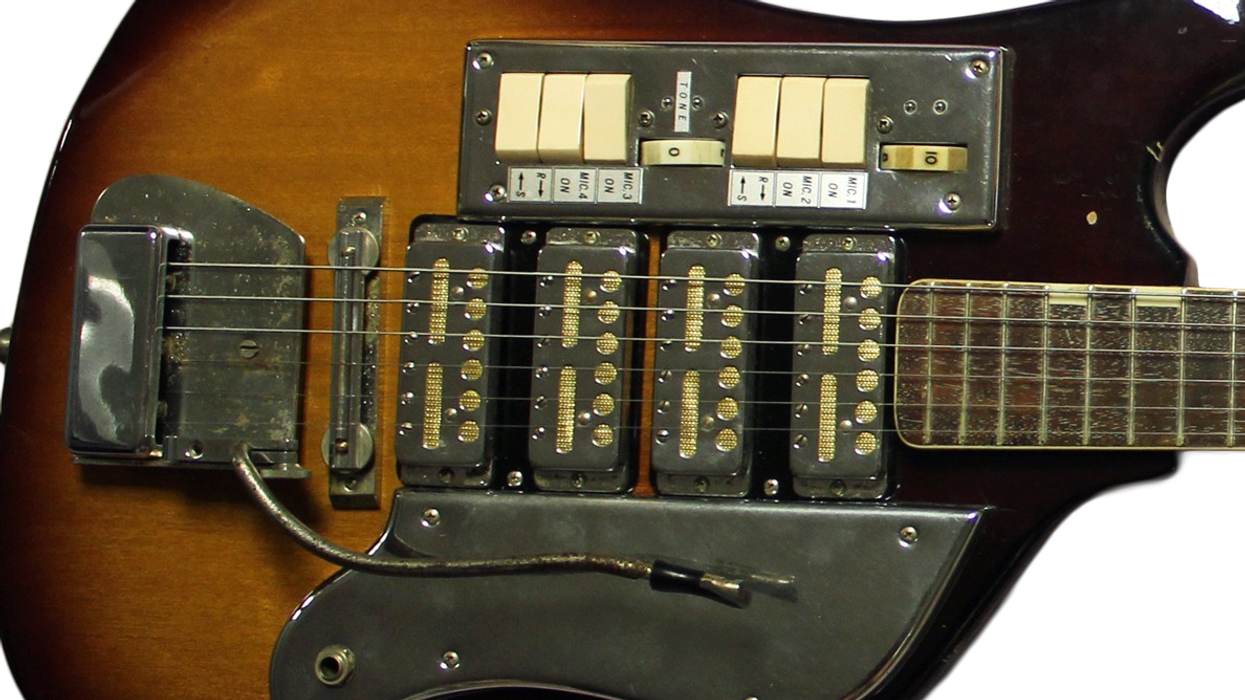

Armed with this knowledge, Yamada began producing some fine guitars. Rather than mass-producing, he kept production low to maintain quality. One of the first solidbody electrics was the Elk Country, which arrived sometime in 1966. In our photo, we can see a few of the hallmarks of Elk guitars. The shrimp-tail headstock and the Elk vibrato are common on many of the models. The vibrato was an in-house design that was made at the amplifier factory. These units work so well, and pair up nicely with the adjustable bridge and tuners.

Now, check out the Jaguar-ish pickups, which are relatively good copies of actual Jaguar pickups. Yamada’s uncle, who was working at an electronics factory in Haneda, took apart the original Jaguar pickup and discovered the use of alnico, which is what gives Elk guitars a great sound that’s full, percussive, and clear. The Country guitar was one of the weirder offerings from the catalog, and didn’t have a very long production run. But you can still see the Jaguar influences in the electronics array that had a volume and tone knob, and two mini switches for the pickup selection. The body has a slightly offset design combined with some exaggerated contours, and this guitar just speaks to my love of the oddballs.

Elk guitars were only really sold and marketed in Japan, so finding a good example is difficult. Adding to the rarity is that almost every one of the Elk or Miyuki logos have simply disintegrated over time, leaving only an oval-shaped bare spot on the headstock. The first Elk guitar I ever came across was a very fine straight-up Jaguar copy, which suffered from the missing logo. It took me a few years to figure out the origin of that guitar, and I suspect some of these Elks puzzled others as well.

Elk electric guitar production continued on through the 1970s, featuring mostly copies of Fender, Mosrite, Gibson, and Gretsch designs. The company was endlessly experimenting with ways to improve the product. There are so many funny stories that have been shared with me, mostly by the excellent author Hiroyuki Noguchi. He interviewed some of the original engineers of the day, and they told him about how they used maple slats from old bowling lanes to experiment with laminate, and how they studied public bathhouse soap dishes to learn about celluloid and pickguards! But perhaps the funniest story is how Yamada came upon the “Elk” name. How’s that for a convoluted tale?

Then, in the dream, I “awoke” and realized I was back in my bedroom, and it was all just a dream. The kicker is that I was still dreaming, because that “paddle” guitar was suddenly in my hands—then I woke up for real! How about that misadventure?

Then, in the dream, I “awoke” and realized I was back in my bedroom, and it was all just a dream. The kicker is that I was still dreaming, because that “paddle” guitar was suddenly in my hands—then I woke up for real! How about that misadventure?

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)