Search

Latest Stories

Start your day right!

Get latest updates and insights delivered to your inbox.

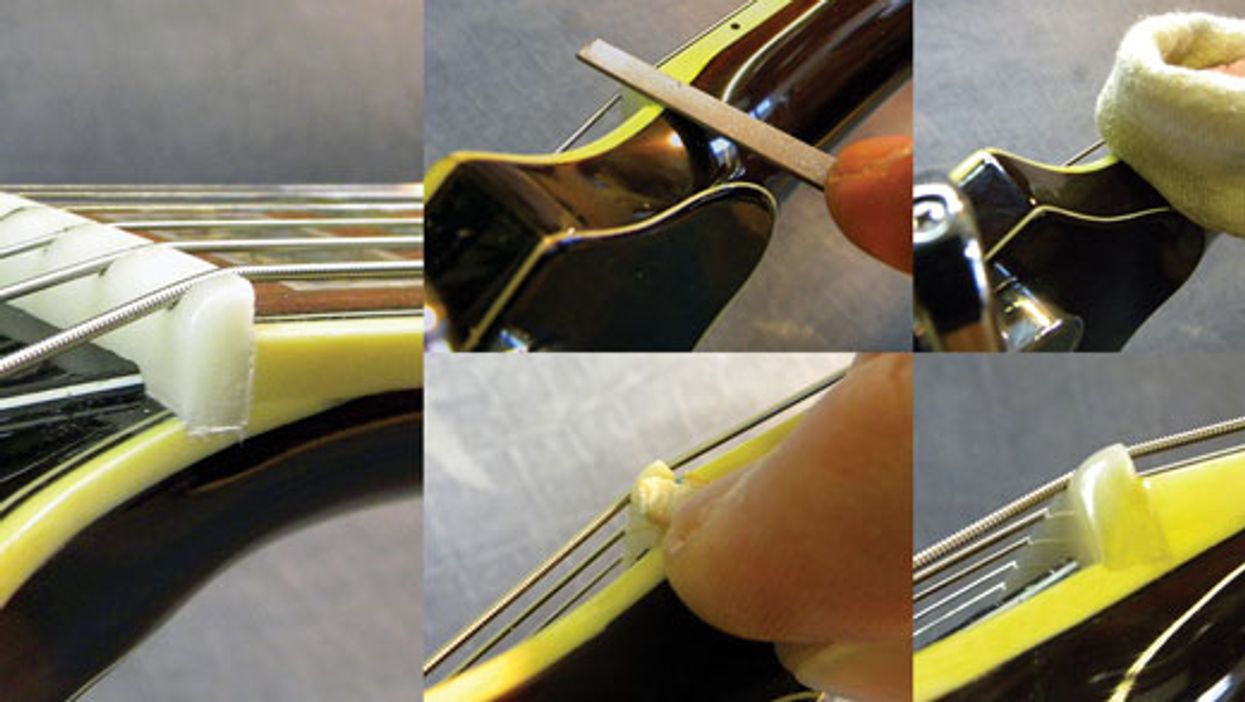

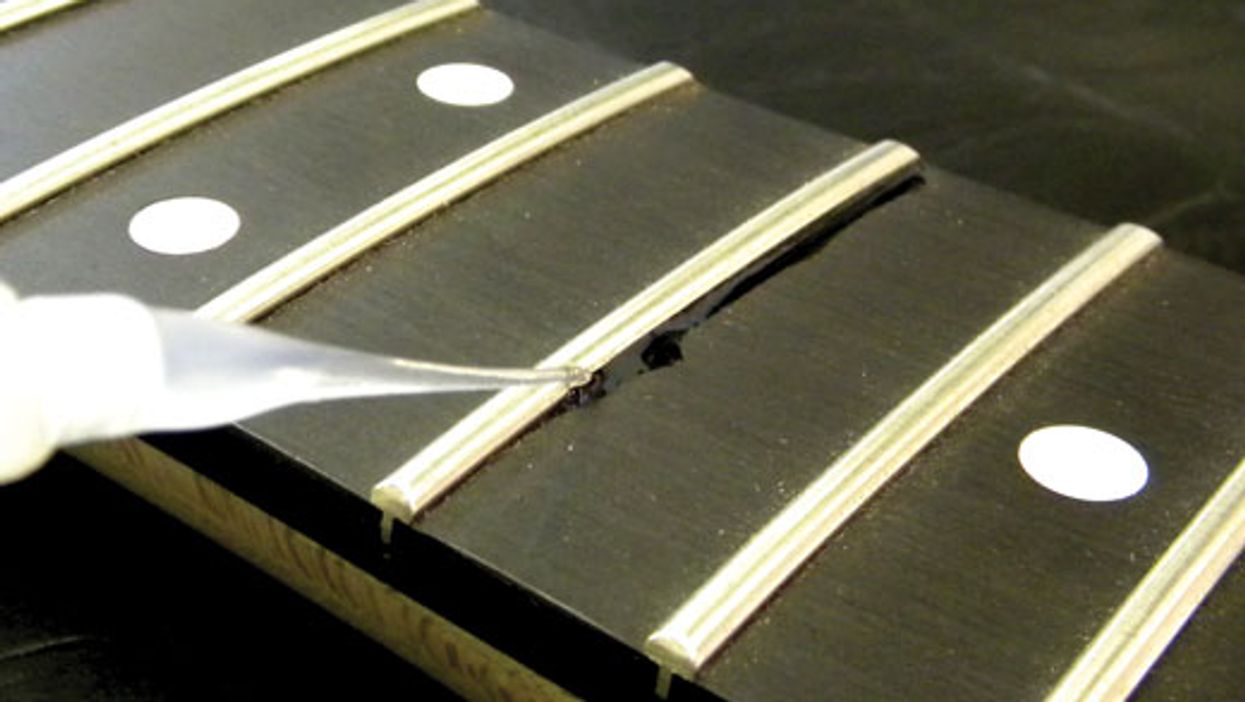

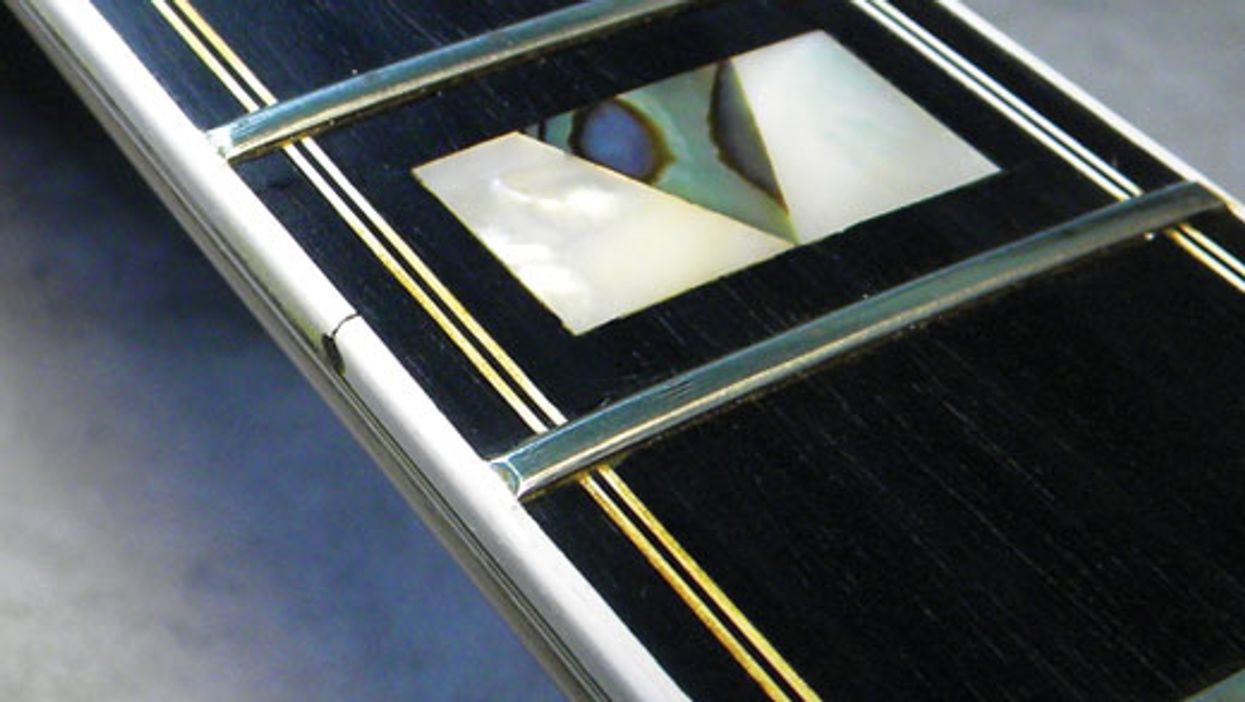

Guitar Shop 101

Dedicated guitarists need to know how to maintain their prized instruments. Nashville guitar tech John LeVan shares all his tips and techniques in this photo-rich blog, and if you wonder what it takes to keep your guitar in gig-worthy condition, Guitar Shop 101 provides the answers. If there’s a topic you’d like to see addressed, drop LeVan an email at guitarservices@aol.com.

Don’t Miss Out

Get the latest updates and insights delivered to your inbox.

Popular

Recent

load more