A few years ago, I saw a video clip of Nirvana’s Krist Novoselic describing his relationship with Kurt Cobain. In the clip, Krist talked about searching pawnshops for left-handed guitars for Kurt. Krist said every time Kurt was able to find a new guitar, he became infatuated with it, and his obsession with his new instrument would spawn 10 new songs. It didn’t matter what kind of guitar it was, as long as it was affordable and playable.

I like this story because I’ve often felt that way about amps. To my mind, guitar amplifiers are instruments, just like guitars, and each amp offers a voice and soul that contains a handful of songs to be mined.

If you can somehow avoid name recognition or snobbery, there may be a ton of good old amps to be found and probably a ton of songs to be written. To find sleeper amps, you need to venture into old shops and look for gear that has been there so long it’s become part of the store’s décor. You have to go second- and third-level thinking here: Think about miking smaller, low-powered amps, and think about pairing two amps via a switching box. And finally, don’t rely on the opinions of others. Use your own ears and create that noise! Here are seven nearly forgotten models worthy of that cause.

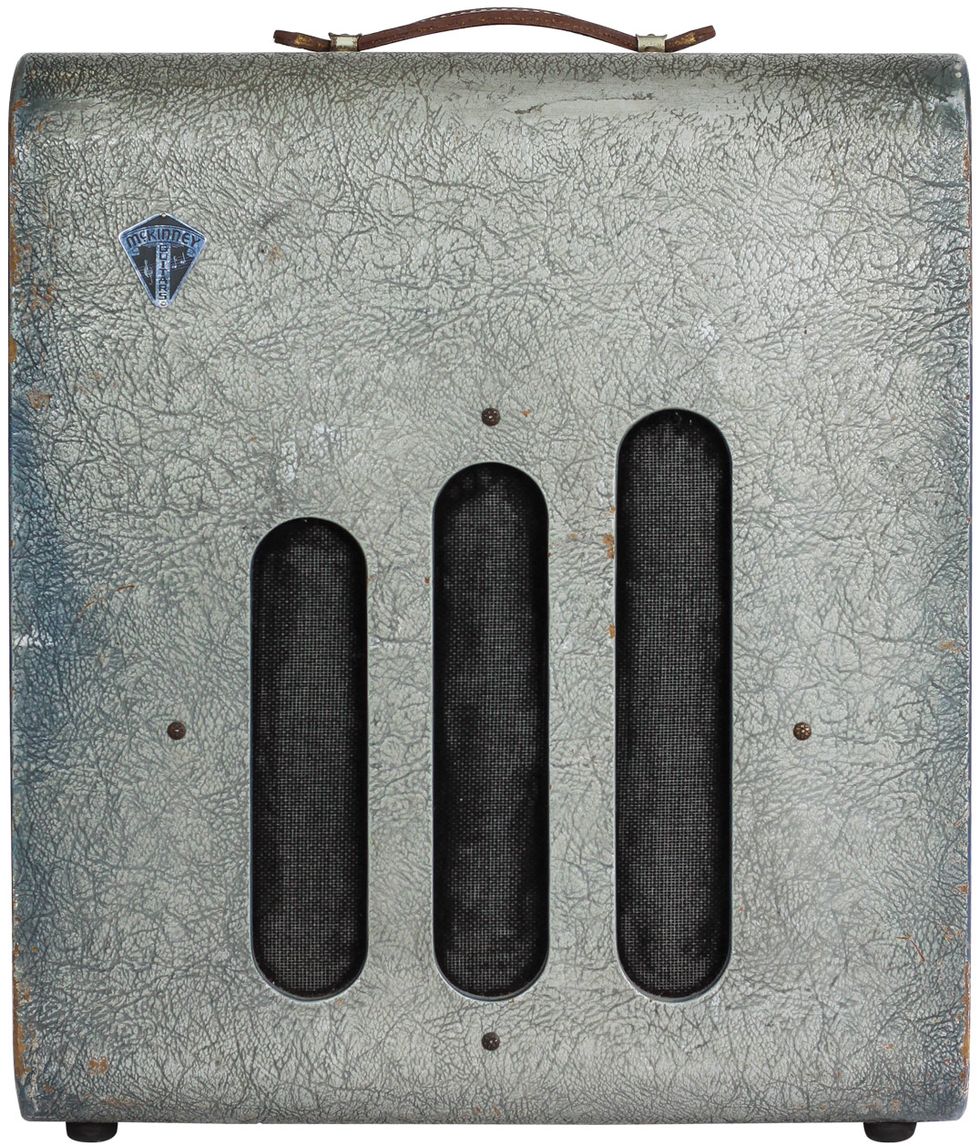

On the Valco-made McKinney 1260, the separate volume controls for the microphone and instrument channels reveal the amp’s original all-in-one design as a vocal PA and guitar amplifier. But they give modern guitarists’ two different,

delicious breakup flavors

McKinney 1260

Dating from 1948, this amp is the oldest of the group and probably the most ferocious. Back in the day, the Valco Company of Chicago was making amps and guitars under many different brand names, and this McKinney is just one example. This line was sold through the McKinney School of Music in Peoria, Illinois. If you study old Valco catalogs, you’ll notice that many of the amps of that time were sold with a lap-steel guitar, so most of these early amps were low-powered and voiced for a certain style of music. Then, in the late 1940s, Valco started to produce amps voiced for more powerful guitar pickups, crystal microphones, and changing musical styles. We’re talking about the dawn of rock ’n’ roll here!This same McKinney amp can also be found in the 1949 National catalog as model 1260. It cost $165 at the time and produces about 16 watts of power. What makes this amp interesting and probably historically important is that it was one of the first Valco guitar amps to use 6L6 power tubes. In this same catalog, another amp called the 1215 “Professional” featured even more power via 6L6 tubes. These two models were certainly the top-of-the-line guitar amps in their day.

There are many, many great sounding Valco amps spanning about three decades, but these early amps offer a unique sonic experience. If you’re at all interested in a vintage tone, then this amp is authentic in every way. The 1260 has a fine combination of old-time tube overdrive mixed with some serious output and power. It features two channels with a volume control for each, plus a shared tone control. The instrument channel is very responsive, loud, and crisp. The microphone channel is just nuts. It’s a bit louder and offers some unreal breakup through the 12" speaker.

I’m not a big fan of modifying amps, but I did replace the original Jensen 12" speaker in this McKinney to preserve and protect it from my fuzz pedals. The 1260 originally came with a field-coil speaker, but a good tech can change it over to a magnet speaker without modifying the amp’s B+ power supply, so you’ll still have that same great tone. Another easy mod that can be done on some of these old Valcos is to install a line-out circuit using a 1/4" female jack from the output transformer secondary. Then you can plug into another amp or PA system for an unbelievably huge sound!

This reverb-equipped Airline amp was a Danelectro-made sister to the Res-O-Glas Airline guitars favored by a lineage of nasty players from bluesman J.B. Hutto to Jack White. They’re not loud, but they’re vicious—especially with humbuckers.

Airline 9013

This Airline 9013 was sold through Montgomery Ward department store catalogs and is another example of an amp that was made under several brand names. This killer little amplifier, which chugs along at about 15 watts, first appeared in 1962 and was made in New Jersey by Danelectro. The president, founder, and sole owner of the company in those days was Nat Daniel, and man, the guy was just an incredible innovator who knew how to get amps and guitars into the hands of kids all over the U.S.The 9013 was promoted in advertisements as a “Regular Amplifier” that sat in the lower price range of $70. Interestingly, the more expensive “Professional” Airline amps were made by Valco. The circuit of the 9013 is essentially identical to the Danelectro-made Silvertone 1482 amp (with the vertical control panel) sold through Sears.

To keep costs down, Danelectro used some sort of pressed paper or particleboard for the cabinet construction. Basically, these amps don’t travel very well and you definitely don’t want to spill your drink on one of them. But the benefit of these cabinets is the entire amp only weighs around 26 pounds.

The amp runs on a pair of 6V6 power tubes and the deep, pulsating tremolo goes through a 6AU6, which creates a lovely effect. This was one of the first amps I ever fell in love with, and although it doesn’t create room-shaking volume, what it does create is a fantastic overdrive that I’ve used in lieu of an effects pedal.

Seriously, just run an A/B box between this and your main amplifier and you have a 26-pound overdrive that will be more authentic than any pedal you can muster up. Also, these amps feature four inputs so you can jump channels using a short pedal cable for even more aggressive tones. These came with decent speakers, usually Jensen or Fisher models, and they provide a truly authentic vintage tone. Think Chicago blues, circa 1965.

Longtime amp tech Ernie McKibben pointed out that many of the Danelectro amps were voiced for lower-output single-coil pickups, which explains why these amps have so much crunch with humbuckers and mini-humbuckers. In fact, thinking about an amp’s original design and intention can force you to consider guitar and pickup choices, and open up new avenues in your playing.

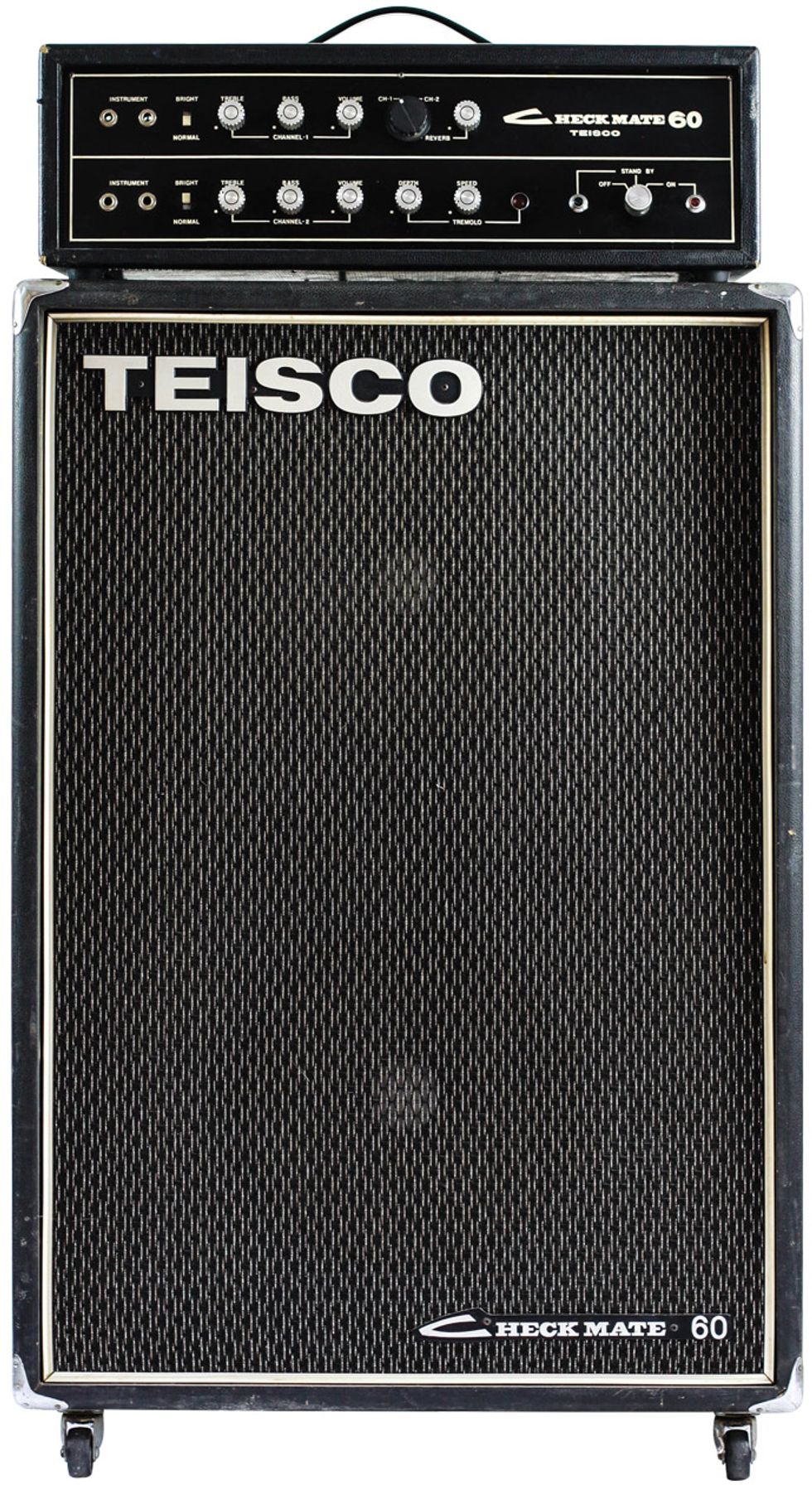

Despite bearing the Teisco name, the Checkmate 45 delivered the goods: soulful tones, sweet reverb and vibrato, and enough 6L6 output to power a dance party at a beach bar. So did its louder sibling, the Checkmate 60.

Teisco Checkmate 45

This obscure piggyback Teisco dates to late 1965 and was one of the first large Teisco amps made for the American market, with the proper U.S. voltages. This Checkmate 45 eventually morphed into the more common Checkmate 50 in 1966 and was being made alongside the even more common Teisco Checkmate 25. Many players scoff at even the mention of the Teisco brand, since the company has always had a reputation for making cheap guitars and inferior products. But if you simply use your ears and avoid popular opinion, you can have a great sounding amp that offers up some inspiring tones.During the mid 1960s, Teisco was working hard to improve their products for the U.S. mass market. The company’s engineers labored tirelessly to up the build quality in an effort to gain a foothold at middle price points.

In reality, these 1960s piggyback tube models were among the best ever produced by Teisco, and this level of quality continued until the late 1960s. The Teisco amp line was never farmed out to different companies, which meant these amps were made in the same Tokyo factory for many years.

This Checkmate 45 runs on a pair of 6L6 power tubes and cranks out a good amount of volume, though it can sound a little strained depending on the guitar and pickups you use. There’s also a cute “E” oscillator tuner switch to help you tune your guitar, complete with a headphone jack.

The amp has dual channels (each featuring two inputs) with reverb and vibrato. Experimenting with the channels and inputs yields a great array of tones, and, for whatever reason, this amp just sounds tight. It’s hard to describe, but this is the kind of amp that was destined to play surf music or vintage spaghetti-Western movie soundtracks.

I also want to mention the larger Teisco Checkmate 60, which dates to 1968. One option offered to players of that time was the ability to pair amp heads with various cabinet configurations. Occasionally you’ll see odd pairings, such as 2x15 speaker cabs or two 10" cabinets that both sport the same amp head model. The idea was to purchase the cabinet that best fit your audience. It was a short-lived concept, but the number of cabinet choices was something to behold. The Checkmate 60 runs on EL34 power tubes and just sounds über-aggressive with the 2x12 alnico speakers in a lightweight, yet solid cabinet.

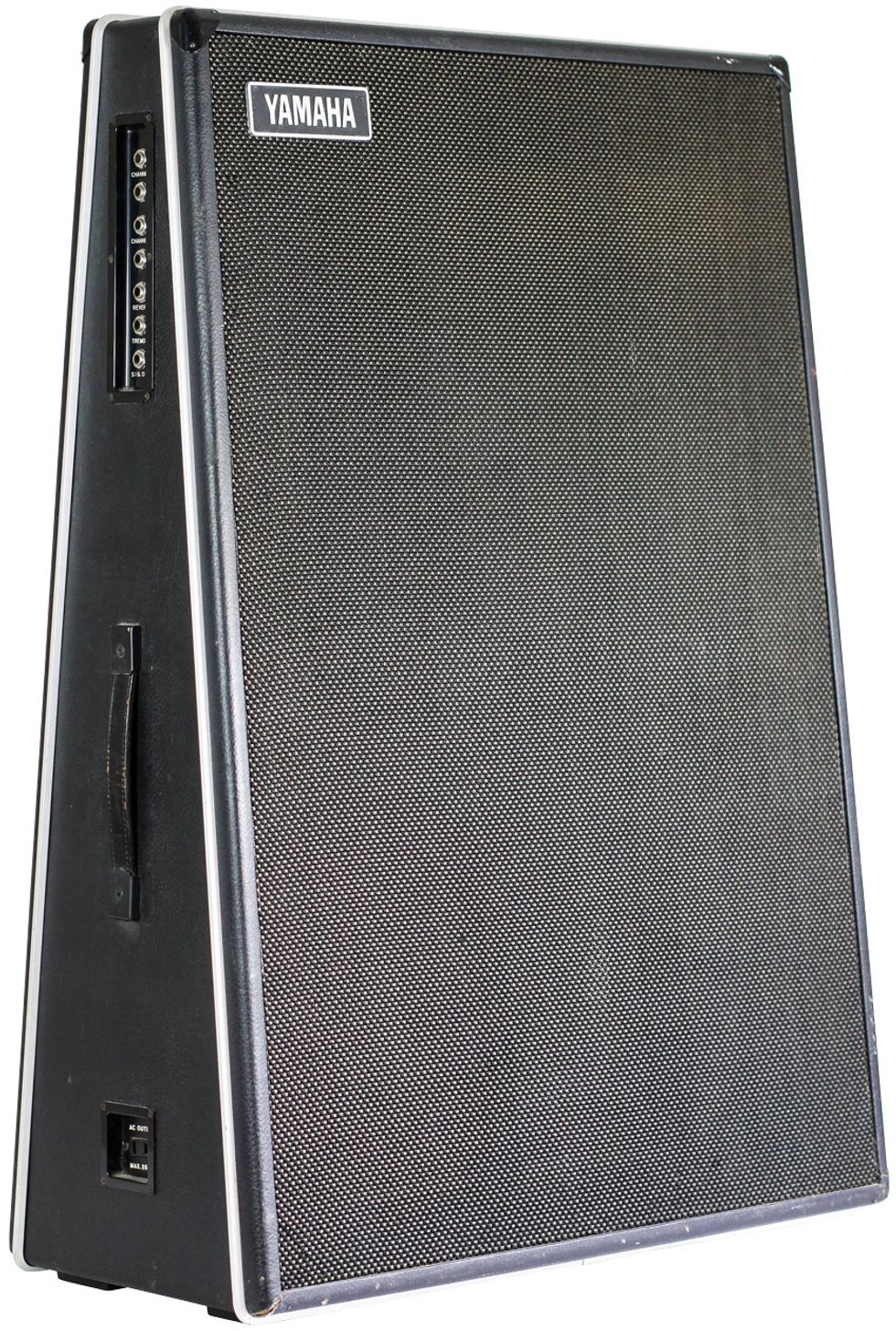

This futuristic looking Yamaha amp had an interior that strove to be equally cutting-edge, with solid-state circuitry, flat Flexion speakers, and then-new silicon transistors and diodes.

Yamaha TA-60

Made during the late ’60s and early ’70s, these truly original amps were sold alongside the equally interesting Yamaha SG guitars. I often hear players bemoan copied designs and lack of originality among current guitar makers, and to these people I point to Yamaha products of the late 1960s. This TA-60 amp is totally gonzo. The wedge shape and strange speakers and the ethereal tones are just out of control. The shape was innovative at the time because the engineers were thinking about a fresh look combined with a low center of gravity, so the amps wouldn’t be accidentally knocked over. These amps make a statement in every aesthetic way.The solid-state circuit touted the use of “new” silicon transistors and diodes (as opposed to germanium), and the wedge shape supported Yamaha’s flat Flexion speaker design. Advertised as “Natural Sound” speakers, these units were a complete departure from traditional speakers. They were described as having a “non-directional” design featuring a “columnar crystal magnet.” Made of some sort of white plastic, Flexion speakers have an extremely flat trapezoidal shape.

The TA-60 weighs around 46 pounds and claims to produce 60 watts of undistorted “music power.” I can say the TA-60 can achieve serious volume and can fill a good-sized room with a kind of crazy space-age sound. The tone of these amps is just about indescribable. It’s airy, spacey, and open. Try to imagine your guitar sounds reverberating off a piano soundboard. There is a lot of variation to explore when plugging into the two channels and dual “High-Low” inputs. When cranked, these amps can get plenty aggressive, but because there’s already so much coloration going on in the circuit, I’ve found they don’t take pedals very well. Really, every studio should have an amp like this.

The TA-60 cost a whopping $650 in late 1967 and was marked down to $480 in 1968. There was also a smaller TA-30 and a larger TA-120 amp offered during the same time. Studying old Yamaha catalogs, it seems that these wedge amps disappeared by 1971, although the Natural Sound speakers continued in different variations in other audio applications. Most notably, these same speakers achieved some horrific infamy in early-’70s Fender Bantam bass amps. Used in this Fender bass amp, the speakers had a high rate of failure and just sounded bad.

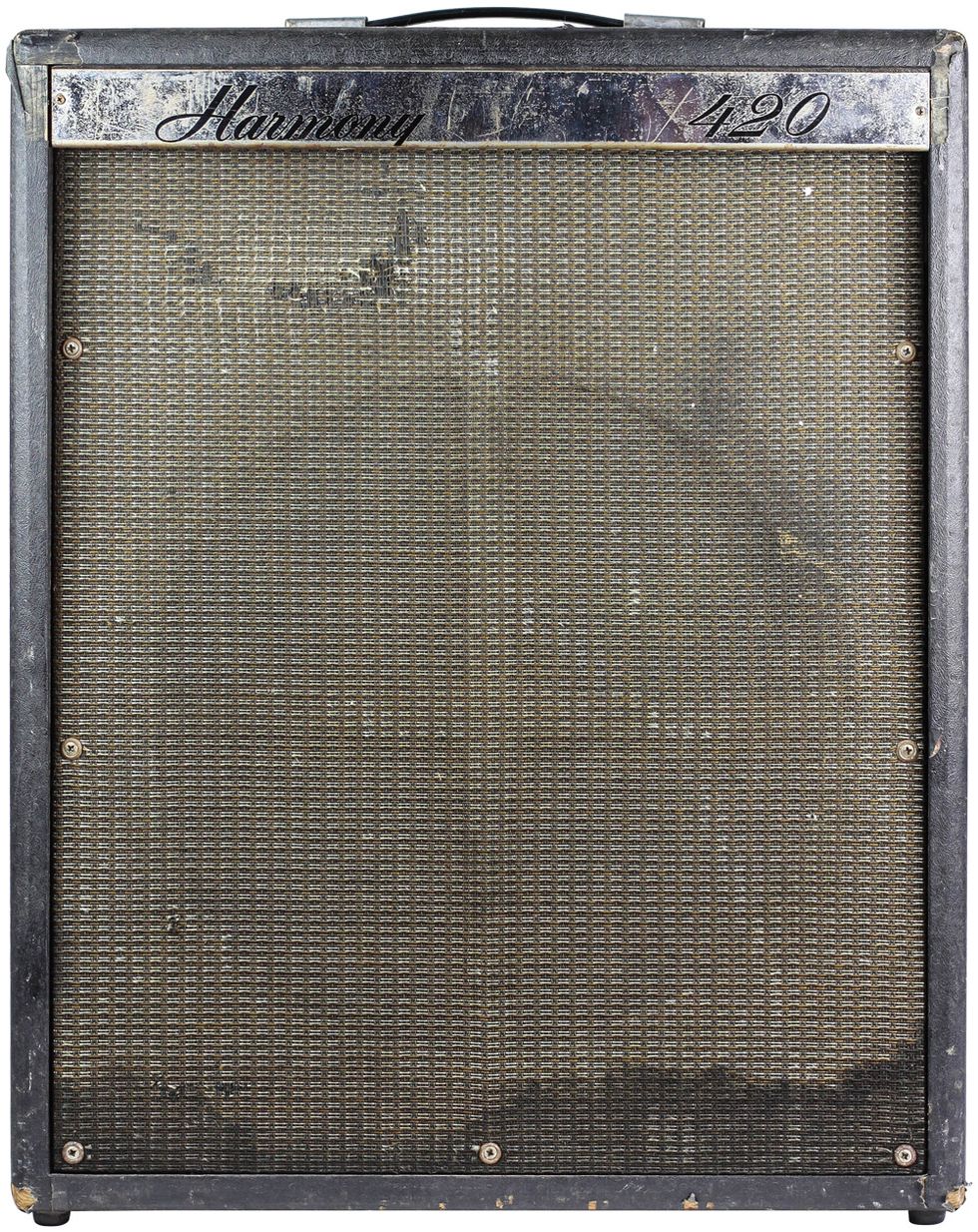

A Valco variation on the famed Supro Thunderbolt, the Harmony 420 has a solid-state rectifier, verses the Thunderbolt’s tube rectifier, and individual bass and treble controls.

Harmony 420

Though this old Harmony 420 bass amp looks like I fished it out of a river, I found this one in an old bar/dance hall in Delaware where it served out its years as a backup stage amp. This poor old guy sure has been around the block a few times, or, as my grandpa used to say, it’s “been through the mill.”This is another amp built by Valco and is pretty much the same as the more famous Supro Thunderbolt, except for a few changes. For one, these 420 amps have a solid-state rectifier and separate bass and treble controls (the Thunderbolt had a single tone pot). The 420 also has a different cabinet design, with the controls on the top of the amp rather than the lower back of the Thunderbolt. So does the 420 sound the same as the Thunderbolt? They’re very close, but the price comparison between the two amps makes for an easy decision because the 420 gets you at least 90 percent of the way there, often at less than half the cost. Both amps even featured the same Jensen C15P speaker.

A lot of amp makers in the 1960s struggled to create appealing models for bass guitar, and this one is no exception. Playing a bass through these amps is simply an uninspiring experience. Although the 420 is voiced darker than a regular guitar amp, it provides some really nice, glassy clean tones for guitars. Also, the amp takes pedals very well. The wood and the cabinet design on these amps is nice, and unlike Danelectro-made amps, they do travel well.

These cost around $200 in 1966 and were marketed as providing “powerful amplification” with “minimum distortion.” That does hold somewhat true, as the 420 used a pair of 6L6 tubes for the output. Later versions of this amp featured a cool red-racing-stripe motif, and, of course, following the Valco way, there were several similar amp circuits made under the Airline and Gretsch brand names as well.

The Contessa lives up to its name as sleeper amp royalty, with plenty of volume and clean headroom, excellent garage-rock tone, onboard tremolo and reverb, and quiet operation.

Hohner Contessa CA200

About 10 years ago, I saw this Hohner amp in a music store in upstate New York and I was smitten. The swirly grill cloth … interesting. The little Hohner emblem guy playing an accordion … dig it. The “Contessa” name … never heard of that one! It turns out this amp was made by a New Jersey-based company called Sano. Sano amplification began shortly after WWII with a focus on amplifiers and electric pickups for accordions, but eventually branched out into guitar amps with all sorts of cool speaker configurations. Many people believe that Sano and Ampeg were in some way related companies, but the reality is that they were two separate entities with no real business relationship. Sano made amps primarily for their own brand, but did make amps under the Hohner and Excelsior names. One thing about Sano amps during this era: They were versatile and voiced to fit a wide range of different instruments, such as accordions and vocal microphones.There are several legendary Sano amps out there, and this CA200 is one of the best. Sano also made this amp under its own name and called it the GS-20. Driven by a pair of 6BQ5 (EL84) power tubes, the CA200 has some truly milkshake-thick distortion. Combined with a large, well-built cabinet, the amp just projects like a cannon. When used with lower output pickups, there is some nice clean headroom to be found way up on the volume knob. But with hotter pickups, this amp is searing at about half-volume. This is a circuit that works well with pedals, but you really won’t need many because the onboard tremolo and long-pan reverb are outstanding.

The CA200 sat right in the middle of the Hohner guitar amp lineup, weighing around 33 pounds and sporting a 12" speaker. These have one channel, but it’s a really good one. Pumping out about 20 watts of power, these amps have a really cool vintage garage-rock tone. They somehow sound raw and refined at the same time. Also, I’ve found Sano amps in general to be some of the quietest operating amps on the vintage market. These make for excellent recording amps and every Sano I’ve owned or played has been very resistant to hum and noise.

After locating an old catalog, I found that in 1969 Hohner marketed four amp models: three for guitar and one large “general purpose” amplifier called the Orgaphon. The CA200 was priced at $230 in 1969, but for the money you were getting a fine guitar amp—then and now.

This model was Ace Tone’s early-’70s flagship amp, with about 100 watts on tap, and came in several cabinet configurations—all as heavy as they sounded. One quirk: a built-in VU meter to monitor overloading.

Ace Tone Solid Ace 10

There was a time when I once avoided solid-state amps at all costs, and it had to do with an old ’80s Peavey amp I used to own. I can’t remember the exact model anymore, but that amp sounded so sterile and lifeless that it scarred me for a few years. That injury lasted until I started trying out early solid-state amps from the ’60s and ’70s. There is something about early solid-state amps that sounds more organic and natural than newer amps of the same ilk. It’s hard to pin down, but one listen to some of the old Ace Tone amps and you’ll dig.I’ve always known the Ace Tone name from old fuzz boxes, like the awesome FM-2 Fuzz Master, but I never really knew much about Ace Tone amps. It turns out that Ace Tone was started in the early ’60s as a maker of electronic musical instruments such as organs, effects, and drum machines. The mastermind behind the company was Ikutaro Kakehashi, and his designs were innovative and original. Eventually Kakehashi left his Ace Tone company in the early ’70s to start the more famous Roland Corporation.

The Solid Ace 10 was the company’s flagship amp in 1971 and could be purchased with a number of different cabinet configurations. The head alone cost $420 new and ran a whopping $1,200 with twin-column speaker cabinets housing four 15" speakers. These are 2-channel amps full of “red-blooded” tone (per the catalog) and had enough power for “3 acres of auditorium.” Gotta love vintage ad hype!

Similar to the mid-’60s Teisco amps, Ace Tone amp heads could be ordered with any number of speaker cabinets. This one came with a 2x15 cabinet that weighs close to 100 pounds. It’s a true widow-maker! Now with all this power—something like 100 watts—on tap, there is a curious, yet cool VU meter to warn of overloading. But if you somehow manage to overload this amp, then you probably deserve a trophy. The two 15" Japanese Gold Bond speakers feature a cool golden cap cover, à la JBL speakers. The stock speakers feature alnico 5 magnets and sound superb. This amp takes pedals very well and, as expected, this Ace will rattle the house even at lower volumes.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)