From the age of 5, I'd begun taking things apart—toys in particular. For as long as I can remember, I've had an unyielding drive to learn how things worked. How my parents dealt with this was to either threaten never to buy another toy or, later, by offering more complex toys along with a stern warning that if it got taken apart, I had better figure out how to put it back together. What came of that was a developing gift for not only putting things back together, but to ensure that one couldn't tell I'd ever had them apart. Such was the intellectual battle in our house between young adults learning to be parents, and a kid struggling to outwit them.

One great respite from this tug-o'-war was spending two weeks every summer with my grandparents on their farm in rural Washington state. In a small familial community of Italian immigrant homesteaders, there were two ways of handling broken-down cars and appliances: Fix 'em yourself or put 'em out to pasture. For a super-curious kid with plenty of time on his hands, watching the grown-ups apply their dogged determination to eke out another season of utility from a lawn mower or chainsaw was a revelation. Grown-ups took things apart and put them back together, too! But what was, for me, merely a gnawing curiosity was, for them, perhaps having extra money in the savings jar for the electric bill.

One day I watched as Grampa Joe and Uncle John pulled apart a lawn mower engine to change the points and adjust the spark plug gap. I was consumed. If there was one thing you learned in an environment like this, it was how many barns in a half-mile radius housed a sidelined power mower. I remember lying awake most of that night waiting for the rooster to call out the sunrise, and soon I was off searching out an abandoned mower to play mechanic on. I struck pay dirt in Uncle John's barn, and in no time, I was hard at work—and a bit nervous. Could a lone 9-year-old kid with only rusty tools and zero experience replicate what two adults had accomplished the previous day?

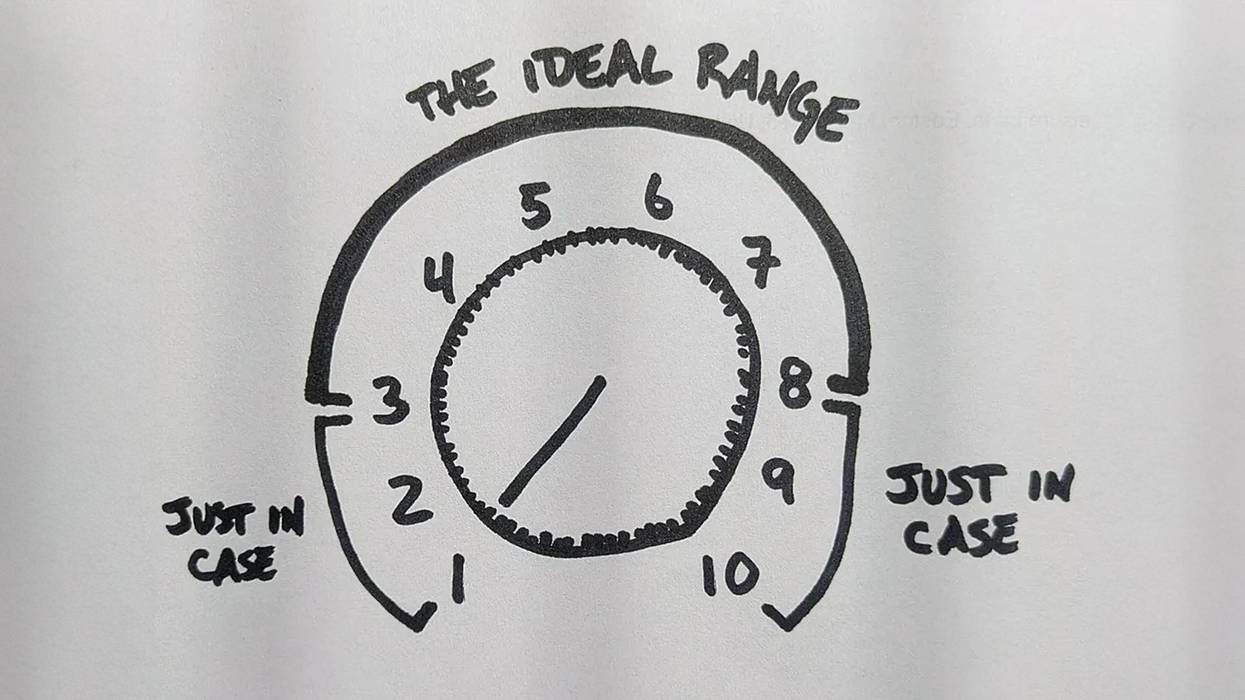

I soon ran into my first major obstacle. Joe had rented a wheel-puller the day before to get that flywheel off. I'd never seen a wheel-puller before that, let alone a flywheel, but I understood the concept. The rented tool had been returned, so I made do by splitting a small block of wood into two doorstop-shaped pieces and gently inserting them under opposite sides of the flywheel. By carefully tapping alternate sides, I gradually lifted the flywheel off the main shaft, and soon I was filing the corroded ignition points and spark plug using Grandma Letizia's nail file. I had no way to gap the plug, so I had to wing it, tapping it with a rock to close the gap, and prying it open with a screwdriver until I thought it looked about right. Satisfied, I put the whole thing back together, poured in some fresh gasoline from a jug in the back of Letizia's Model T and gave the cord a yank. You can't imagine my surprise when that thing roared to life, and I just could not believe my luck.

Letizia had a garden around back of the house, and John's house was right next door, so I mowed a small patch of lawn near the garden to make sure everyone heard the noise of the newly revived mower. Sure enough, they all came out to see what was up. Uncle John was the first to ask me how I got that thing running. “I just did what you and Grandpa did yesterday." Uncle John's face went from surprise to a big, broad smile. He then reached into his pocket, pulled out a $5 bill and held it out to me. “No thanks," I said. “I don't want money." “Well, what do you want?" asked Grampa Joe. “I want that Philco radio in the spare bedroom."

I'd been eyeing that imposing 1936 floor-model radio for over a week. Grandma said it didn't work, and that's all anyone knew. Now it belonged to me and I immediately plugged it in and turned it on. It stood silent for a few minutes and then gradually a hum emerged from the large 13" electromagnetic speaker. Just a low insistent hum. No other sound, and no determined adults around to bail me out. Still, I was fascinated with that beast and I got permission to take it back home with me when my folks came to pick me up.

Within a couple of years, I was learning about electronics, reading library books, and making regular weekend bus trips to First Avenue—skid row—in downtown Seattle to visit a funky little surplus electronics store called Standard Radio. The place was dingy, with row after row of bins full of familiar and unfamiliar bits of mostly obsolete electronic parts and tangled cloth-covered wire that smelled of burnt varnish and decomposing wax. After a number of visits, the owner, a self-proclaimed “First Avenue Philosopher" gradually warmed up to the precocious kid with endless questions.

Over time, things my Standard Radio sage taught me began to mesh with the stuff I'd been reading at the library. On one of these visits, I took the plunge and bought a power supply I'd become fascinated with. It had a large power transformer, a big Coke-bottle-shaped rectifier tube, a couple of cylindrical metal capacitors, and a thing that I later learned was called a choke. I had purchased a voltmeter that I built from a kit, so I had a real piece of test equipment and just as the label on my new gadget said, this power supply was reading 450 volts! My folks never had a clue what I was up to. It all seemed harmless and only elicited the occasional “be careful" from Mom. Interestingly, the parts in that power supply closely resembled some of the parts in my prized Philco radio, and I began to realize I might actually have a shot at getting it to work.

From what I learned messing with that power supply, I replaced the filter cap and brought the Philco back to life. And the funny thing is, now that I knew a bit about what was going on in there, it started to lose its mystical hold on me. I guess I felt I'd conquered it. And then right about that time, something else happened: the Beatles. In an instant, my whole world changed.

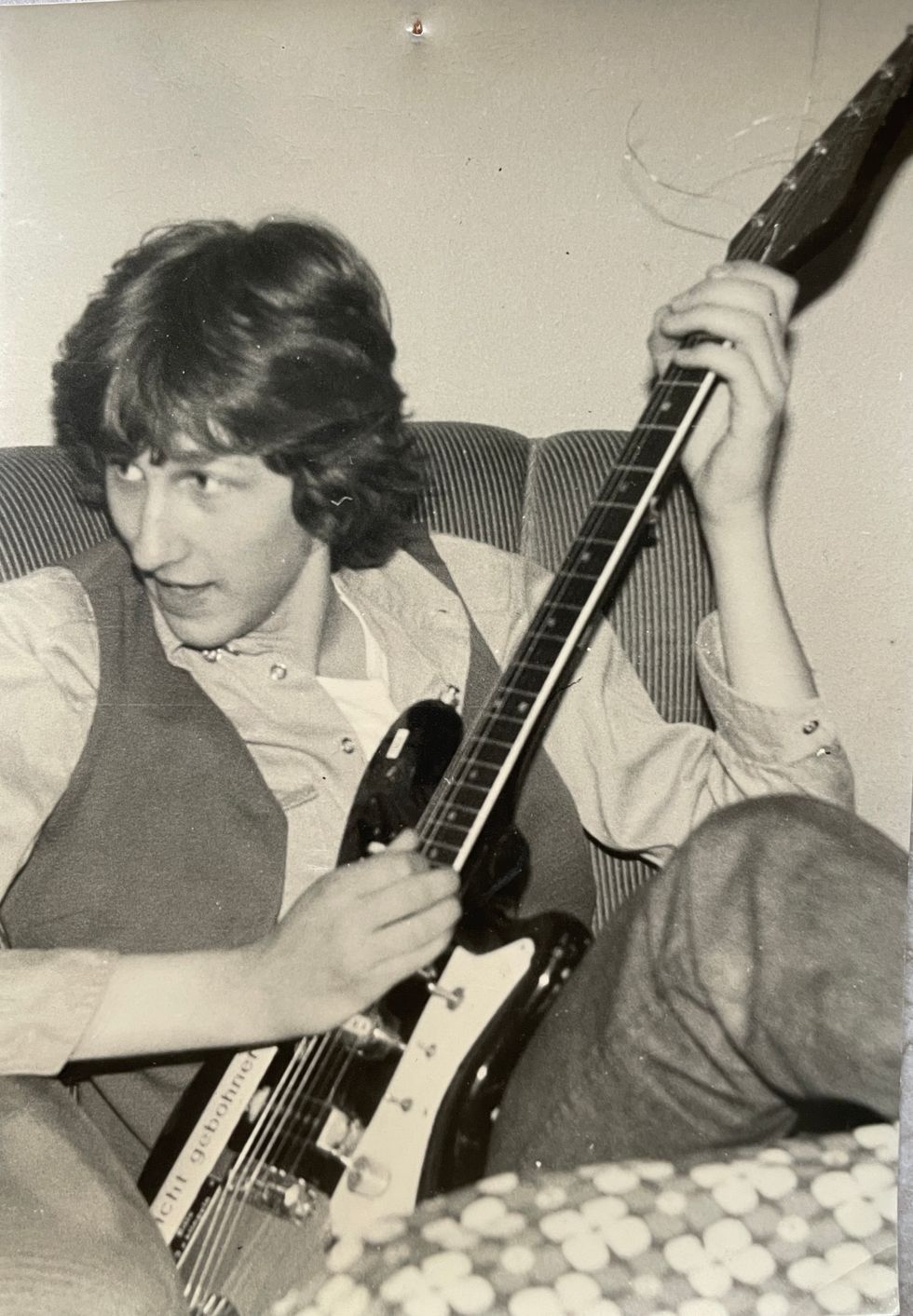

I'd always been musically inclined, and music was omnipresent around our house, but this was something altogether new and exciting. It just obliterated everything else. My older brother and I started a band. We played local dances and people our age came over to play, and the neighbors were getting pissed off. From then on, I knew what I was going to do with my life.

Over time, however, the electronics bug reappeared, and I'd saved up enough money to buy a hi-fi amp kit. It started with a stereo preamp. I needed to save up for the power amp, and I was building speaker enclosures for my dream stereo system in wood shop at school. About that time, my brother got a Fender Concert amp for his birthday. It was big. And loud. It looked professional. And it was off limits.I was still the kid bro who took things apart and this amp wasn't going to be anyone's guinea pig.

Curious thing about that Concert: It had two big tubes in it with 6L6 printed on them, and they looked a lot like two of the tubes in the Philco, which had a pair of tubes labeled 6V6. By then I had learned that the first number designated the tube's filament voltage, and a trip to the library confirmed that the 6V6 was a lower-powered cousin of the 6L6. I was convinced the Philco housed a super power-amp stage behind that Clark Kent exterior, and I was determined to find out.

The Concert amp had the newer “miniature" preamp tubes in it, but I had learned that they were mostly modernized versions of those big Philco tubes, so I went about trying to determine which one was the preamp stage for the power amp. I didn't know what a phase inverter was yet, but I knew you needed the little tubes to boost the signal up enough to push the big ones. And I knew what a grid was. I also learned that touching some of the circuit parts gave you one hell of a shock, while others just made the amp give off a buzzing sound—a clue that noise was being amplified. For those of you wondering if I was ever going to get around to the point of this column, well, here's your first clue.

Without the benefit of a schematic diagram, which I had recently learned how to read (I was 12 at about this time), I had divined the input tube on the Philco power amp. Not only that, but its grid was conveniently located on top of the bottle. The number on the tube was 6K5. I know this because I still have that radio, and it still has the RCA plug I installed on it to use as an external input jack.

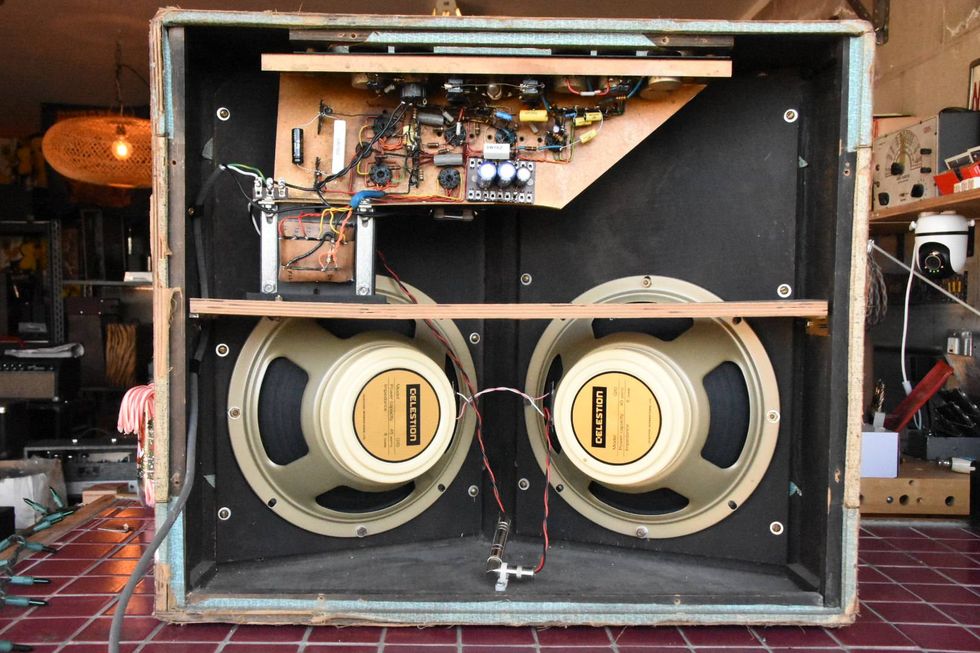

What happened next was as life changing as the first British Invasion. I plugged my stereo preamp into the Philco power amp, put an album on the turntable, and out came a loud, distorted, one-channel rendition of whatever that album was. What changed my life was not listening to the record, but the realization that I was just a short hop away from turning this contraption into a bona fide guitar amp. And that I did (Photo 1).

Fate had made our basement a rehearsal room and there were plenty of football practice sessions to keep my brother occupied after school. This afforded me the time to spirit his guitar up to my room and plug into the auxiliary input of my preamp. I flicked on the power switch, turned the volume all the way up, and there it was: a fearsome howling noise that was at once horrendous and beautiful. That feedback, crackling, and heinous speaker overload opened the door to a whole new universe for a musically inclined electronics nerd to explore.

About that time Jimi Hendrix had burst onto the scene, and the sound of that first album put the noise emanating from my Philco amp into sharp perspective. Later, Chicago Transit Authority was released, and the liner notes described the Bogen preamp-driven rig Terry Kath used to create the screaming sonic fury that was “Free Form Guitar." I couldn't believe the coincidence of these events, given the trajectory of my recent discoveries.

Something was pulling on me, and I was all in….

Welcome to my new column, Signal to Noise. My name is Steven Fryette. I took you on this long, convoluted introduction to illustrate, as best I can, where I came from, how I got here, and maybe attempt to explain why I can't imagine following a different path than the one I'm on today. This is where I live and where I belong. I hope you'll enjoy seeing this column unfold as much as I enjoy exploring the phenomenon of turning a small signal from the strings under your fingers into the glorious wall of harmonics that make up the beautiful noise of our lives.