Photo by Steven Park

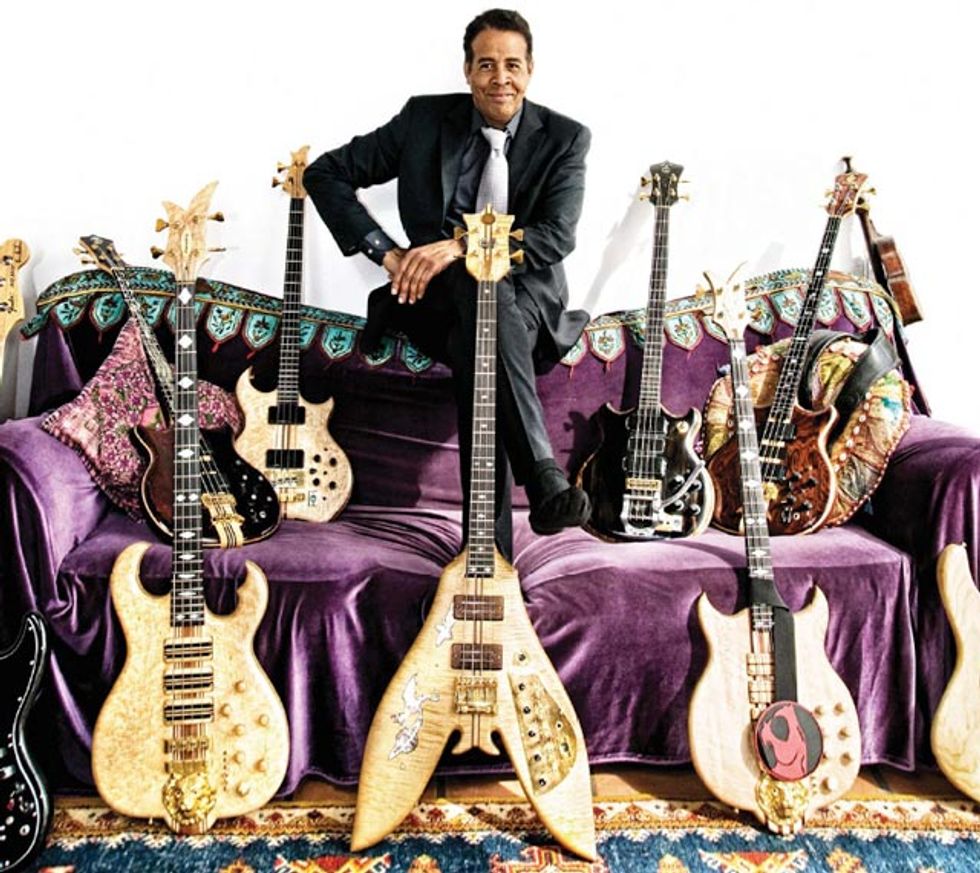

For those in the know, the name Stanley Clarke brings many things to mind—beautiful Alembic basses … funky slap solos … a big Afro ... and, most likely, Return to Forever. Founded by legendary keyboardist Chick Corea in 1972, Return to Forever—along with John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra and Joe Zawinul and Wayne Shorter’s Weather Report—was hugely instrumental (no pun intended) in establishing the jazz-fusion genre. Though RTF has included such noted players as session drummer Steve Gadd and guitarists Al Di Meola, Earl Klugh, Bill Connors, and Frank Gambale (who currently plays with the band), Clarke is the only member other than Corea who’s been there from the get-go. Through this and other vehicles, Clarke became one of a handful of 1970s bassists who brought electric bass to the forefront and gave it a solo voice of its own.

In addition to RTF work, Clarke’s prodigious musical accomplishments over the years include collaborations with the likes of Jeff Beck, Ron Wood, Larry Carlton, Jean Luc Ponty, Stewart Copeland, and fellow bass gods Marcus Miller and Victor Wooten. He also has a formidable track record in film scoring with credits including such feature films as Boyz N the Hood and Like Mike 2, television series like Lincoln Heights and Soul Food, made-for-TV movies such as Murder She Wrote and The Red Sneakers, and even Michael Jackson’s video for “Remember the Time.”

Considering that Clarke’s stellar career as a bassist has centered on the electric, the last thing you might associate with him is the upright bass. But all of that changed when he and longtime RTF drummer Lenny White reunited with Corea for this year’s Forever. In fact, after 2010’s Stanley Clarke Band album won a Grammy for Best Contemporary Jazz Album, Clarke—now 60 years old— asserted that he might not be recording and performing on electric bass again for quite a while.

“I told Lenny that the worst thing in the world is for a guy over 60 years old to be playing electric bass. I get this picture of an old, fat guy holding an electric bass, and I said, ‘It won’t be me.’”

While the thought of Clarke behind an upright bass may be new for those used to seeing him groove on an Alembic, it’s nothing new for him. He began his musical career at the age of 19, backing jazz greats Horace Silver, Art Blakey, Dexter Gordon, Joe Henderson, and Stan Getz in New York jazz clubs. “I didn’t formally study the electric bass like the kids do today,” Clarke says, “but the acoustic bass is something I studied—I was planning on joining an orchestra.”

When you listen to Clarke’s recent acoustic bass excursions on Forever, his years of developing a unique electric bass style clearly come through. “I’ve always viewed them as two completely different instruments, but the music I play on the electric bass and the music I play on the acoustic bass have a kind of cross-pollination,” he says. “Personally, I think [playing both] makes you a better player on both instruments.”

Forever comes with two discs. The first is a best-of collection that includes tunes from the 2009 RTF Unplugged tour, jazz standards like “On Green Dolphin Street” and “Waltz for Debby,” RTF classics such as “Señor Mouse” and “No Mystery,” and originals by Clarke and Corea. The group’s founder plays acoustic piano on all these songs, while Clarke is mostly on upright. The second disc features studio tracks from rehearsals for a one-off Hollywood Bowl concert that kicked off their world tour. It includes Corea, Clarke, and White, as well as Jean Luc Ponty on violin, singer Chaka Khan, and original RTF guitarist Bill Connors. On this disc, the acoustic tunes are mixed with electric-driven tracks in the more traditional RTF vein, with Corea getting behind his synths and Clarke bringing out his trusty Alembics.

Rather than taking the trio back on the road, though, Clarke, Corea, and White decided to support the US launch of Forever with a new Return to Forever touring band that includes Ponty and Australian sweep-picking master Gambale, who has recorded and performed with Corea several times over the years.

We spoke with Clarke recently about the double album, his collaboration with Miller and Wooten, his to-die-for gear, and his philosophies on music as a vocation.

Although the first Forever disc features acoustic-jazz instrumentation, you can definitely hear jazz-fusion thinking within the straight-ahead stuff.

Yeah. It’s very difficult to have a partition between genres. I think that’s true in all music today. You really have to put your mind into it, like “Okay, it’s straight-ahead and I’m going to do it in the style from 1960 to 1965 Miles Davis.” It’s difficult. I think those days are over. One of the things I love about young players right now is that it’s all there. You even hear hip-hop influences in their stuff. It’s cool.

Stanley Clarke plays his Lemur Music-made upright through a Ampeg SVT-2PRO head and an Ampeg

cab at De Oosterpoort in Groningen, Netherlands, on November 13, 2009. Photo by Klaas Guchelaar

One of the guests on Forever is Chaka Khan. A lot of people think of her as a funk singer because of her groundbreaking work with Rufus in the ’70s, but on this album she sounds like a seasoned jazz singer—she does some sweet scat singing.

Chaka has always been a big, big, big jazz fan. She’s a serious musician, and whenever we call her to sing, she loves to do it. But you have to remember that in the ’70s, she and Rufus had hits and managers that were kind of controlling. That’s all they wanted you to see. The perception of an artist from an audience’s point of view is completely different from what the guys and girls are really like. I know country artists that, if you go to their house, they’ve got Miles Davis and Coltrane on.

Bill Connors also makes a return appearance.

At the end of the last RTF tour, the band and Al Di Meola decided to go separate ways. We were wondering what we should do for the guitar scene, and Chick came up with the idea to call Billy. I didn’t even know if he was still playing. We called him up and he says, “Yeah, I’m still playing.” So he came in and we messed around. He rehearsed a bit with us and took some music home. He came back again and hung out. And so he played with us at the Hollywood Bowl. The thing I like about Billy is that he’s always a warm player—he’s a melodic player. And he still has that.

You’ve been playing with Lenny White since you were teenagers. How would you describe the way you interact musically?

We’re both predictable to each other. That can be a good thing, but it can also be a bad thing. So we have to work on trying to surprise each other and amp the game up. We’ve been together 40 years now. You know, you have this musical mind and two or three people can be the owners of that mind. And that’s a great thing. But what makes it even better is when you challenge it—when you go against that mind. Everyone will start smiling, and it’ll throw everybody back into playing games— it’s great. My logic tells me that maybe it would be boring because we’re both predictable— I know what he’s going to do and he knows what I’m going to do—but I’m pretty sure what we’re doing sounds great.

Clarke thumbs a ride with a triple-pickup Alembic Signature Standard. Photo courtesy of Concord Music Group

Your 2008 album, Thunder, with Marcus Miller and Victor Wooten is quite a contrast to what you’re doing now. What was it like playing with those remarkable bassists?

You know, I’ve been playing with other bassists for a long, long time—back to New York in the early ’70s with bass choirs. I think it’s very important to play with other bass players, because it forces you to really bring your musicality up. You can’t just go in and survive with technique. When I played with Victor and Marcus, we were lucky in that we had a natural orchestration. Marcus loves to play low all the time. Victor likes to play in the middle, high … well, he’s kind of all over the bass. I was playing tenor bass and piccolo bass. I was the guy laying out the harmony or comping. If there was a melody, I would either play it or support the melody harmonically.

But it was a challenge trying to come up with music that works for three basses. I don’t think many people know this, but some promoters actually didn’t want to have us play, because they thought we would blow up their PA or that it wouldn’t sound musical—that it would be just a bunch of rumbles and that we were just taking advantage of our names. Obviously, that wasn’t the case. It was a really fun experience for me, because it forced me and Marcus and Victor to really play different. The only time we played like ourselves was when we played individual solos. Marcus did that along with a bass clarinet thing. I chose to play an acoustic bass solo, which was great, because I was in front of a lot of kids who were there because of Victor and had probably never even seen an acoustic bass. We plan to get back together again maybe at the end of next year. I told those guys that I don’t know if I’ll even be playing electric bass by then … we’ll see.

Let’s talk about gear. What electric basses are you playing?

I still play an Alembic bass. They just made a brand-new one for me. It’s absolutely the best Alembic bass I ever heard in my life. I’ve been with those guys a long time. I like playing their basses. I would never dare say that it’s the best bass in the world—I don’t believe in that kind of thinking— but this bass is good for me because I’m used to it. It’s got a good sound.

Tell us about your electric-bass amp rig.

I’ve been playing stereo bass for a long time, so I have a bi-amped system. My cabinet configuration is either two 15s on the bottom or 18s on the bottom. And I have 10s, or sometimes eight-inch speakers, to deal with the treble. Now this is something I got from Chris Squire: I split off the treble into another set of speakers—usually small guitar amps, just to give it a little edge on the stage.

Because it’s a stereo rig, not only do I have all the EQ possibilities on the bass and the amp, but I also have the ability to use phasing between the low pickup and the high pickup. Essentially, it’s like I’m running two basses at the same time. There are a lot of possibilities. And I’m using a TC Electronic G-System. I had to find something really clean because the Alembic bass isn’t naturally warm.

Clarke tracking his 2009 Jazz in the Garden album with pianist Hiromi

Uehara and drummer Lenny White. Photo courtesy of Concord Music Group

You used to play SWR amps, but now you’re endorsing Ampeg.

I like SWR a lot, but when we travel today we sometimes have to rent a backline—especially when I’m doing my own tour. Return to Forever is different. It’s a bigger scene, so we carry our own equipment. When I go into a city, for some reason the Ampeg stuff is always newer. I go into some towns in Europe, and I just can’t find the other stuff. So Ampeg is a better scene for me.

You played the more rocking “Señor Mouse” on electric. Did you think about playing it on upright?

I’ve surprised some people with my upright playing in rock formats. I finally found a pickup that works for me, an Underwood. I’ve tried them all. And I got a bass with a removable neck made for me by Lemur Music. They measured my boyhood bass—the bass I’ve used on all the records I’ve done—and made 14 of them. I kept seven of them. As an acoustic instrument, it sounds okay— it has a nice, sweet sound—but when I put the Underwood pickup on it, it’s a monster. I think the removable neck is the way to go for traveling, too.

What do you use to amplify your uprights?

Ampeg works better for acoustic bass, too. I can compete with the loudest players—I don’t care how loud they are. And this bass actually sounds pretty good with the bow, too. I also use a piece of equipment from a company called EBS—the MicroBass II. I think it’s the best unit you can use for acoustic bass. It has two separate EQs, and they’re really designed for bass. It’s a direct box, but it also has EQ.

Let’s wrap things up by talking about musical careers. What would you like to tell young bassists today?

Try to be as honest as you can. The more honest you are, the more you open yourself up for possibilities and opportunities. Sometimes you’re playing some music and you’re, like, stuck in one thing. If you look around, you’ll find that probably some of the things that are reinforcing that stuck feeling are other people telling you what you should do—whether it’s your wife, your brother, or your bandmate. It’s not a bad thing—it’s nice to be thought of—but I think it helps to really sit back and come up with nine or 10 other things that you’re not doing. If you try those nine or 10 things, you’ll be surprised at what you can get into.

Clarke has multitudes of Alembics, but this Signature Standard is noteworthy

because of its BIgsby tremolo. Photo courtesy of Concord Music Group

In my case, film scoring was completely an accident. I was on this jazz-special TV show, and the director said, “Man, I’ve got this show and I’ve got a couple of episodes coming up that I need some crazy music for. Can you do it?” And I said, “Yeah, sure.” But I didn’t know if I could do it. I knew I could compose, but….

Anyway, it turned out to be Pee-wee’s Playhouse! And you know what? I was nominated for an Emmy Award—and it was, like, by accident. I didn’t even know what an Emmy was. I’ve done 50 films, television movies, and television series … I don’t even know how many of those I’ve done. But it happened in a blink. If I had time, I’d write a book about the things that happen in your life at a blink—and the flip side, the things you decide not to do at a blink. So, to summarize what I just said for a young guy, don’t pass up nothin’. If you have the ability to try it out, try it out.

Stanley Clarke’s Gear Box

CLICK HERE to watch Stanley show us his gear in a Rig Rundown...

Basses

2008 Lemur Music custom upright with removable neck and Underwood pickup, Alembic Series I short-scale electric tenor bass (cocobolo top and back, padauk core, maple-and-padauk neck with ebony fretboard, maple accent laminates), Alembic electric (burled buckeye top and back, padauk core, maple-and-purpleheart neck, ebony fretboard with mother-of-pearl barn-swallow inlays), two custom 34" Spellbinder Siblings electrics designed and built by Thomas Lieber and Rick Turner, Fender Marcus Miller Jazz bass, Lowenherz Stanley Clarke signature model, Kenny Smith Flying Vee, and various Alembics

Amps

Ampeg SVT-2PRO head driving a Pro Neo PN-410HLF cab (for upright), Ampeg SVT-4PRO driving two Pro Neo PN-410HLF cabs and two 1x10 cabs (for electric)

Effects

Two Alembic F-1X tube preamps, TC Electronic GSystem, EBS OctaBass, EBS BassIQ, EBS MicroBass II preamp, EBS DynaVerb, EBS Stanley Clarke Signature wah, Rodenberg GAS 707B Boost

Strings

LaBella stainless electric strings custom wound by Richard Cocco, LaBella 7720S SOLO double-bass strings

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.