Whether through concerted study or a more osmotic process (or somewhere in between), we’ve all spent untold hours learning the melodic, rhythmic, and tonal nuances of our favorite players. Often, probably without even realizing it.

Ambitious players may try to diversify their own approaches by deconstructing music where guitar isn’t central, and surely attentive but less-structured organic learners are influenced by other instruments, too. But whether you’re a regimented student or a principled passivist, there’s a lot to be said for taking cues from the most expressive instrument of all: the human voice. And the better the singers, the better your lessons—though they will be decidedly difficult to translate to our instrument. But perhaps that makes the endeavor even more worth undertaking.

One of my favorite vocalists of all time is Paul “H.R.” Hudson of the legendary D.C. hardcore outfit Bad Brains, which began as a fusion quartet in 1977, but after hearing the Sex Pistols morphed into a prog-punk band prone to fits of soul, reggae, and dub. What was so mind-blowing about H.R. during his prime singing years in the ’80s was his ability to go from a warm, smooth croon to sensual moans and groans, hushed Rasta adulations, rabid barks, soaring wails, rapid-fire jungle rants, and microtonal filigrees—all with a singular style that was notable both for how natural it sounded and for how even its very affected qualities felt 100 percent genuine.

And because of that uncommon range, it may be that translating inspiration from his work to guitar is an even bigger pie-in-the-sky undertaking than I first imagined: It may be that a large portion of its lessons can only be applied to guitar by striving to adopt the attitudes and outlook that bore the music out of him, by attempting to remove inhibitions and respond to musical opportunities in the heat of the moment with no filters. Nevertheless, I will do my best.

One premier quality shining through H.R.’s best work—from the sunny, loose pining on “Stay Close to Me” (off The Omega Sessions) to “Return to Heaven” (I Against I)—is his surety of self. He never shrank from letting his quirks hang out. Other singers might’ve worried, “What will everyone think of how I sound totally laidback and casual in the opening chorus, but come across like a half-crazy/half-stoned zealot in the verse?” But H.R. didn’t give a flying you-know-what. In fact, he’d turn around and ratchet it up to full-on crazy for a split second just to keep you on your toes—all the while never sounding like he was showing off or being weird for weird’s sake.

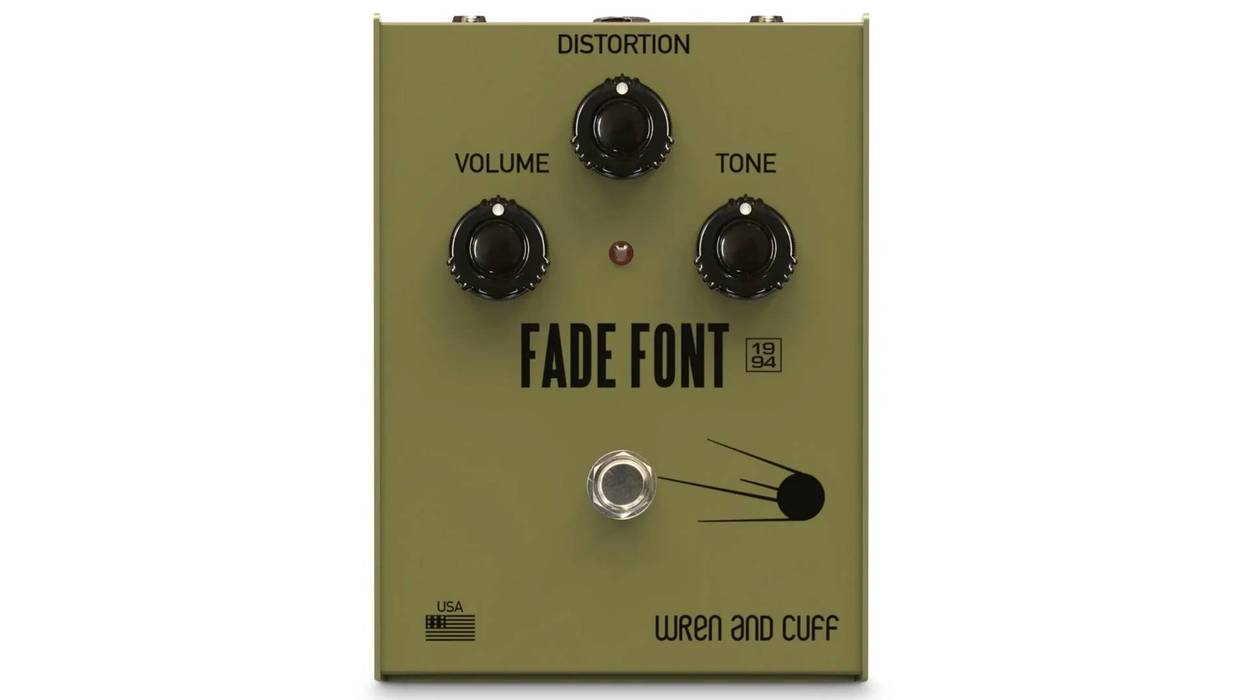

How might one translate this to guitar? For starters, maybe don’t be afraid to let your guitar’s natural extraneous noises ring out. Like H.R. languishing over a seductive intake of breath, exult in the sound of your fingers slowly, gently gliding up the strings. Or maybe use trem-bar resonance or creaking vibrato springs instead of bemoaning them. Avail yourself of both unusual physical techniques and outboard-effect recipes. And don’t just think in terms of notes and chords. Maybe use the percussive capacity of unfretted and/or palm-dampened rhythms, as well as monotonous patterns—think of them as the subconscious, uhhs, umms, and hmms in a hip-hop line or an erotic lyric.

Also, within any given tune, sprinkle in the occasional extreme contrast, be it in pitch, attack (for tactile effect), volume, note duration, speed, phrasing feel (playful vs. melancholy, furious vs. anguished, sedate vs. jubilant), or even in terms of virtuosic vs. raw and sloppy. H.R. demonstrated many of these approaches with aplomb on tracks like “At the Movies” (off Rock for Light), “Supertouch/Shitfit” (Bad Brains), and “Sheba” (Quickness).

The key with all of this, though, is to vigilantly guard against any tactic becoming formulaic or habitual (e.g., based on a favorite lick pattern). This is about ignoring boring norms that’ve become so pervasive in music.

The human voice is the most expressive and most difficult to master because every ounce of it—the willpower and the machinery of sound—comes from within, controlled via a mysterious network of muscles and neurons more complicated than any device on earth. There’s no way a few pieces of wood, metal, and string can match the nuance, but you can get closer by starting to see, and then remove, barriers of society and self that we hardly realize are there. And that challenge is both mental and technical—yet it’s one I’m certain we’ll find fascinating, fun, and richly rewarding to rise to.