Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Intermediate

Lesson Overview:

• Learn how to connect modal fingerings with pentatonic fingerings.

• Approach modes as pentatonic scales with two added notes.

• Alternate between pentatonic and modal thinking.

Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson's notation.

Studying modes can be a confusing, challenging task. Often you may end up with impractical scale fingerings or positions that are not conducive to actually making music. If you’re already familiar with the ever useful and powerful root-position pentatonic fingering, then you most likely know how to use it to improvise and make up melodies. In this lesson, we’ll explore each mode in a familiar way and discover how to use preexisting knowledge to crack its mysteries.

There are many ways to analyze modes, but here’s a definition I like to use: A mode is a variation of a major or minor scale with some altered degrees, and these alterations generate different moods, colors, and vibes. I think of the modes as their own scales and tonalities.

The modes of the major scale can be broken down and simplified into concepts that are already familiar. They translate into a formula—or a string of degrees—as you can see below:

Ionian/major 1–2–3–4–5–6–7

Dorian 1–2–b3–4–5–6–b7

Phrygian 1–b2–b3–4–5–b6–b7

Lydian 1–2–3–#4–5–6–7

Mixolydian 1–2–3–4–5–6–b7

Aeolian/natural minor 1–2–b3–4–5–b6–b7

Locrian 1–b2–b3–4–b5–b6–b7

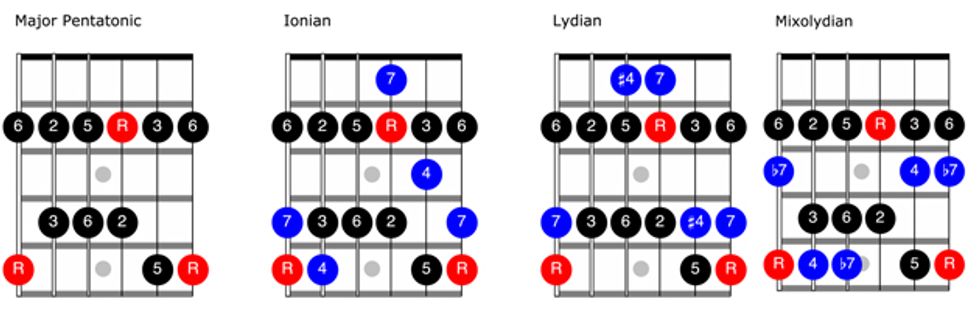

You’ll notice that all the major modes (the ones that contain a 3) have the degrees 1–2–3–5–6 in common, in other words, they all contain a major pentatonic scale. Similarly, except for Locrian (which we’ll address later), all the minor modes (with a b3) have the degrees 1–b3–4–5–b7 in common, and this spells a minor pentatonic scale.

This leads to a conclusion: We can think of a mode as being a five-note pentatonic scale with two added degrees. The Dorian mode is a minor pentatonic with an added 2 and 6, the Lydian mode is a major pentatonic with an added #4 and 7, and so on.

In the guitar microcosm, nothing is more universal than the major and minor pentatonic scales. The classic shape is lick-ready and its easiness on the fingers grants us quick access to a library of blues and rock phrases. It seems like a fairly manageable extra step to inject an additional two notes into the root position fingering. I feel it opens up more opportunities for creating traditional rock licks and finding bend-friendly positions than the three-note-per-string fingerings that are often associated with studying modes.

In the first diagram below, how we start with the basic major pentatonic fingering and then move to Ionian, Lydian, and Mixolydian. The root notes are shown in red and the added notes (not in the pentatonic scale) are in blue. These patterns are not key-specific, so don’t be afraid to move them around to different keys.

The next series of diagrams cover the minor side of the spectrum. Again, we begin with the tried-and-true minor pentatonic and then move on to Dorian, Phrygian, and Aeolian.

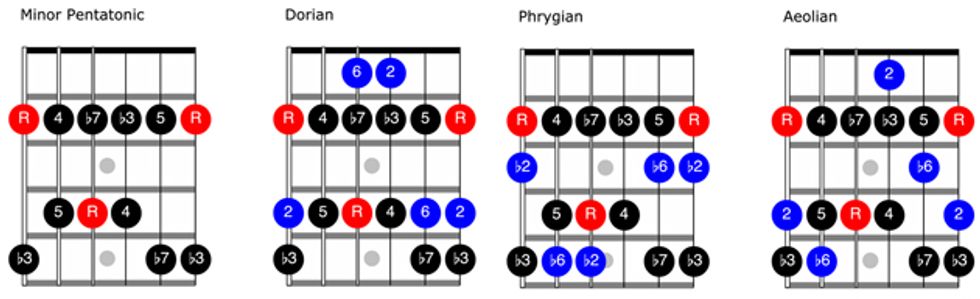

Next, here are some licks based on all those shapes, with a simple root chord underlying to imply context. Instead of following a strict scalar approach, I tend to think of those modal licks as going back and forth between a bluesy, pentatonic inspired portion and a full mode portion with more notes. This usually results in a more soulful, blues-based sound rather than a scale exercise or a finger pattern.

Our first lick (Fig. 1) demonstrates how to incorporate the Ionian sound with the major pentatonic fingering. The real magic in each one of these modes is where the half-steps occur. By bending in and out of those areas, you really get to the essence of the sound— check out the bends on beat one of the third measure and beat three of the fourth measure.

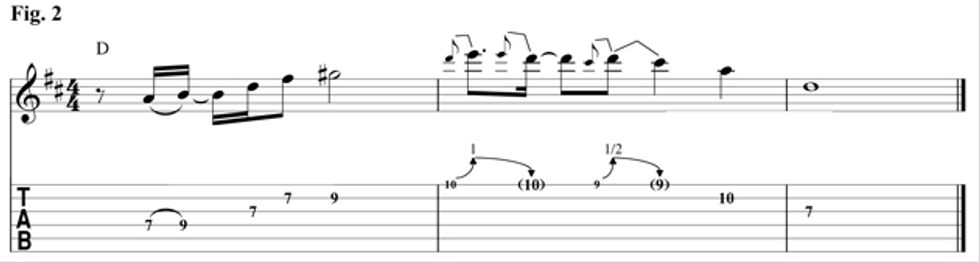

We move on to a D Lydian tonality in Fig. 2. By landing on the G# in the first measure, you can really emphasize the sound of the #4.

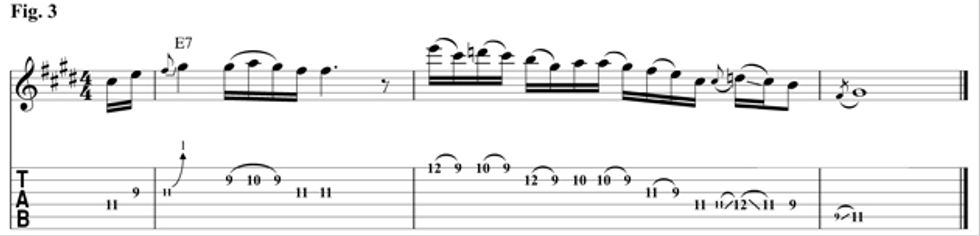

In Fig. 3 we move to the 9th position and work out of an E major pentatonic shape. By adding D natural and F#, we easily move to an E Mixolydian sound.

With Fig. 4, we add the 2 and 6 to the minor pentatonic fingering to create a Dorian sound. Again, we are exploiting the half-steps in the scale with the opening bend and the G-F# move going into beat 4 of the second measure.

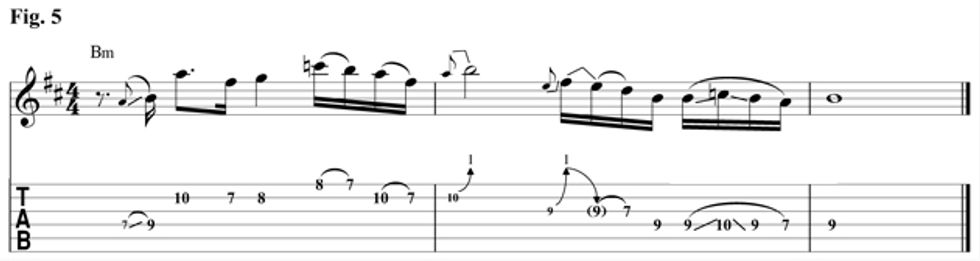

In Fig. 5 we shift to the exotic sounds of the Phrygian mode. Working out of the 7th position B minor pentatonic, we add a b2 (C) and b6 (G) to the scale.

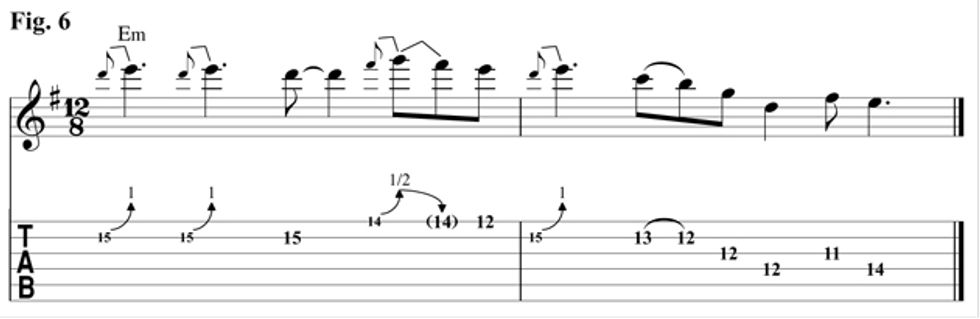

For the Aeolian example in Fig. 6, we change the time signature to 12/8. You can think of this either as 12 eighth-notes or a triplet feel in 4/4. The minor tonality is really expressed in the F#-G bend in the first measure, and the D natural on beat 3 in the second measure.

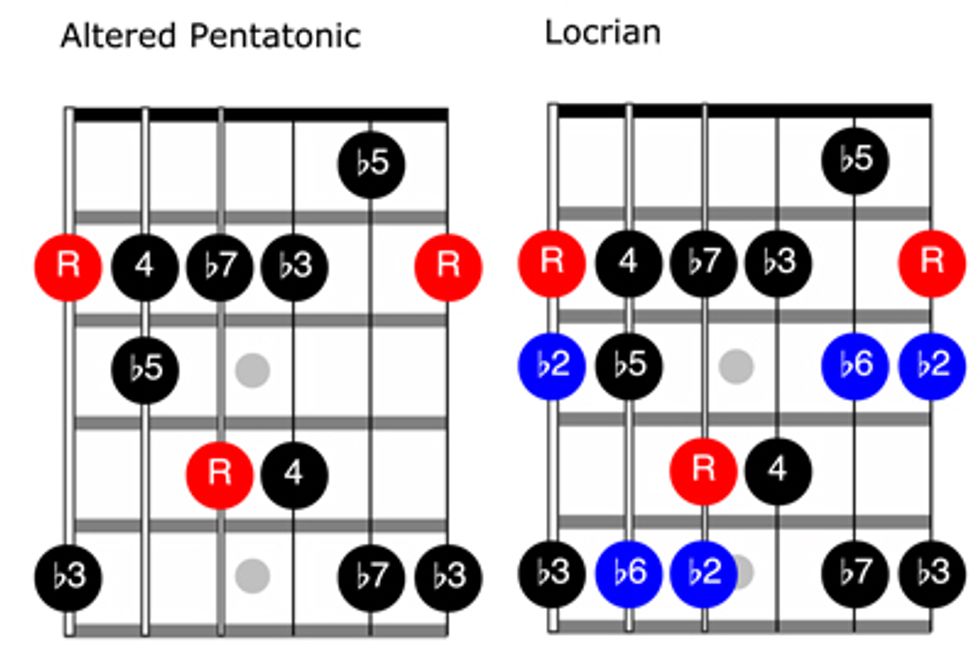

Next, I want to talk a bit about the Locrian mode. Its many altered degrees make it a very unstable tonality, therefore it is hard to truly convey the feeling and mood of Locrian and to establish it as a tonal center. It is often considered more of a “passing mode,” and its associated chords (diminished or m7b5) are also considered passing or transitional, resolving to a more stable and anchored tonality.

Locrian does not contain a proper pentatonic scale, although you’ll find something close if you lower the 5 of a minor pentatonic (1–b3–4–b5–b7), as shown in the diagrams below. This altered pentatonic scale has a mysterious and exotic flavor. When used in moderation, it makes a great alternative to the standard minor pentatonic in a blues context. Throw in a b2 and b6 to this altered minor pentatonic scale and everything adds up.

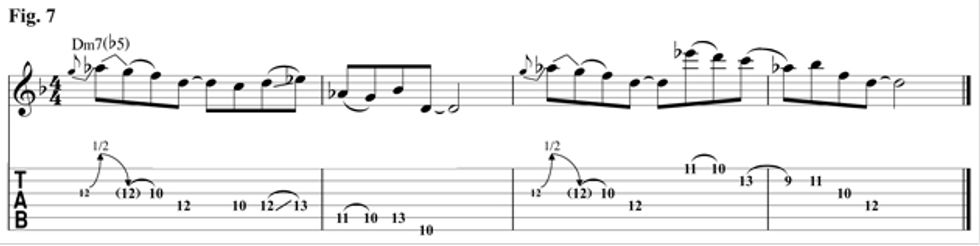

Finally, we work through the somewhat mysterious Locrian mode. The lick in Fig. 7 is an attempt to make it sound like a strong tonal center—or at least a twisted, bluesy phrase.

Sometimes it only takes a simple extension of a very familiar concept to turn something seemingly complex into something completely accessible. You don’t necessarily have to stray too far away from a blues/rock-based vocabulary to open up a melodically and harmonically richer palette. At the same time, your modal melodic choices don’t have to sound too scientific or overly calculated. There’s always a happy medium. You can lean more one way or the other, and your choices will display your taste and make your playing original.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)