“This all comes full circle.” Dwight Yoakam was on a storyteller’s roll too good to interrupt, and he knew it. But he also hadn’t forgotten that he was answering a question about the high-energy sound of his new album. For 10 minutes, he riffed on Buck Owens, the evolution of country rock, and why he chose to self-produce after years of collaborating with legendary guitarist/producer Pete Anderson. Yet in the end, Yoakam brought it home, closing the circle by explaining what all of this had to do with his current touring and recording band, and how they brought sonic power to his new album, Second Hand Heart.

Actually, “full circle” is a good way to describe Yoakam, circa 2015. Long before the term “Americana” was in the musical lexicon, he was blending rootsy sounds that resonated with the traditionalists in cowboy boots while it won over a healthy chunk of rockers (or maybe it was the other way around). Nearly 30 years ago, the honky-tonk energy of his debut album Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc. brought lean muscle to a country music scene that was pudgy around the middle.

Now, after more than a decade on indie labels and major-label subsidiaries, he’s back on Reprise. Yet in some ways, Yoakam falls as far outside the Nashville mainstream as he did back in the 1980s. In contrast to the Auto-Tuned, arena-rock sound that’s been ruling the country charts, Second Hand Heart sounds pure, direct, and unvarnished. The songs, written mostly by Yoakam, are built on a classic country-rock foundation of twangy guitars, first-position chord progressions, and, of course, Yoakam’s hillbilly-tinged vocals. But they’re also full of enough little surprises to keep you guessing—and enough rocking riffs to make you want to grab an axe and play along.

at lead runs.”

On the phone from Los Angeles, Yoakam had the easygoing enthusiasm of the guy sitting on the next barstool, sometimes making his points by singing them. It’s obvious that even after nine platinum albums, two Grammys, and countless other career milestones, the man from Pikeville, Kentucky, remains an ardent student of American roots music.

If I didn’t know better before hearing Second Hand Heart, I would have thought, that’s a good band album. How did you get that sound?

You’re hearing a sense of abandon. Starting with [2005’s] Blame the Vain, I’ve used my live band for recording. And I kind of “cast”—for lack of a better term—the musicians that suit what I’m trying to do. I worked for many, many years, successfully and with great pride, with Pete Anderson. Then I decided to make a change. I’d left Warner Bros., I was kind of doing an indie thing. Pete and I did one indie album [2003’s Population Me] and a few years went by before I began to do the next one [Blame the Vain] for New West. I was performing at that point with [lead guitarist] Keith Gattis. We did a little acoustic duo run together, back in early 2003. And that bled into the following year and then I said, “You know, I’ve got to go out and do dates that were booked this summer, and I need a band.”

It’s not common for solo country artists to use the same players on tour and in the studio.

That’s the thing that was distinctive about Buck Owens’ music when he exploded onto the scene. He took his live honky-tonk band into the studio. His touring band was his recording band. So that’s why those records sound like that. And that’s what I did on the first two albums.

Dwight Yoakam credits Beck with inspiring him to play more electric guitar in the studio.

Your guitar playing is an important part of that sound.

Believe me, I know my limitations. You’re not going to see me out there sliding across the stage on my knees, flailing away at lead runs. I’m not a soloist, but I’m okay at my rhythm and riff thing.

What inspired you to play more electric?

Beck [Hansen] and I collaborated on “A Heart Like Mine,” the first track I recorded for 3 Pears [2012]. We were kicking around a couple of ideas in his home studio. I said, “I’ve got this thing, let’s put it down.” I played an electric rhythm track that I thought was a scratch—a guide for somebody like Keith Gattis. But Beck said, “We’re going to do another track of that guitar. Look, you and I could each call five guys to come in and play this note-for-note, but Dwight, it wouldn’t be that.”

I knew what he meant: It was the intent. We ended up building the track out of my parts, and there’s just a certain recklessness to it, because I’m an acoustic guitar player—basically a bluegrass player.

Pete Anderson used to call from the studio and say, “You’ve got to come in and play the acoustic.” I’d say, “Well, maybe.” On my records there’d sometimes be these fingerpicked parts that I wanted very beautifully articulated. Great studio guys would play this stuff. But for the most part, anything that was hillbilly or bluegrass, I had to play. Pete would just look at me and say, “You’re going to do it.”

Because your playing may have something the studio guys can’t capture.

I don’t fingerpick, I flatpick. When I play bluegrass, I use crosspicking, and I approach my songs the same way. It creates a different attack. I don’t have that kind of beautiful, elegant virtuoso rolling like Pete does with his fingerpicking, but Beck made me believe that maybe what I did was halfway worthwhile.

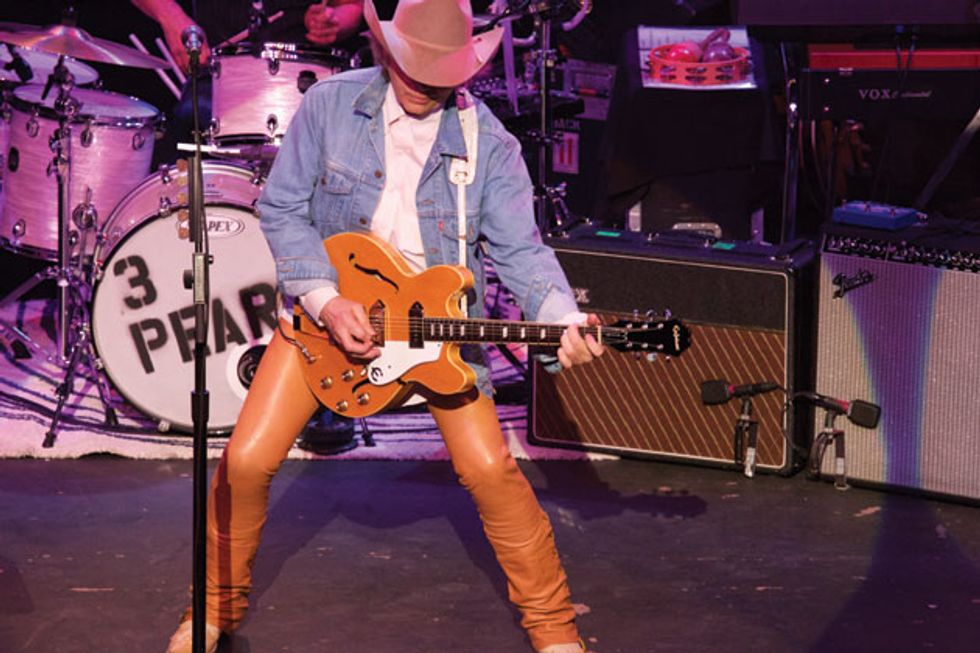

Yoakam’s go-to electric is the Epiphone Casino Elitist—the Japanese-made copy that is modeled after the original Casinos from the mid ’60s. Why? “Those P-90 pickups,” he says.

What was your go-to electric guitar on Second Hand Heart?

My Epiphone Casino. It’s an Elitist model—the Japanese-made copy that’s true to the original Casinos from the mid ’60s. I love that guitar, the sonic soul of it is all over this album, and was also all over 3 Pears. Those P-90 pickups—hey, you know, if it’s good enough for the Beatles on Revolver all the way through “Revolution,” I guess it’s good enough for me to trash around with. I use heavier strings on the electric. Years ago I started stringing up with jazz sets that include a wound G, but I’m still not in Stevie Ray Vaughan territory.

How did you approach tracking the guitars on this album?

I came back to [lead guitarist] Eugene Edwards, who’s played with me now since the release of 3 Pears. We went in as a unit and recorded as a band. I didn’t overdub the countermelody stuff—I let them play it. That’s what I think you’re hearing—and I’ve come full circle now on that first question!

Can you share a memorable moment from those sessions?

On “Liar,” I was showing the band the progression while we were getting mic sounds. I was in the iso room at Capitol Studio B singing, and the guys were out there live. I looked at [engineer] Marc DeSisto and said, “You know, you oughta record this anyway, just for kicks.” He hit record, and that’s the track. What you hear is the first time we played “Liar” as a band. I played electric rhythm guitar using that Casino through a Vox AC30. It’s Eugene out there with the “Dwight Trash” Casino that Epiphone made for me.

The Dwight Trash Casino? Please explain.

I loved my Casino so much I had them build another version. I said, “I’ve got an idea. I want to monkey around a little bit. The [Gibson Firebird] reverso headstock ... can you put that on the Casino? I’d like to see how that looks.”

So they made it for a couple of years. The headstock change altered the tone a little bit. I found that for my sound, the Elitist with the original headstock still had a little more of the brashness, the breakup. But this one was wildly great. I played it on 3 Pears, but then I gave it to Eugene to use as the lead guitar on this album. He used it on “In Another World”—pretty much everything. There are only a couple moments of Tele lead. I think Brian Whelan played Tele on the lead for “Man of Constant Sorrow.” Almost everything else is that Dwight Trash Casino doing the lead guitar part.

Dwight Yoakam's Gear

Guitars

2001 and 2004 blonde Epiphone Elitist Casinos with P-90s

1978 sunburst Fender Telecaster with three-piece ash body

Two 2011 Gibson J-200 True Vintage series acoustics

Amps

Vox AC30 with Blue Bulldog speakers

Fender Super Reverb reissue

Fender Deluxe Reverb reissues (modified by Robert Dixon)

Acoustic Amps

Fender SFX (used as a preamp)

Crown XLS 1500 power amp

Peavey speaker cabinet

Effects

Morley ABC Selector/Combiner (amp switcher)

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EJ21 Nickel Wound Jazz Light (.012–.052)

Martin Marquis 92/8 Phosphor Bronze (.013–.056)

Fender 351 medium picks (tortoise shell)

How did Chris Lord-Alge become co-producer?

He was going to mix the album and said, “I want to come by the studio and watch what you’re doing in there, see how you’re delivering this to me.” I’d cut the song “Believe”—another guitar part with the Casino—and I was going to have Brian play Telecaster, but Chris interrupted. He said, “You just did it. We like what you just did. Just play it on the Tele.” We ended up doing a second track like that. People think it’s a 12-string, but it’s actually two 6-string Telecasters. He took over the session, and that’s how he ended up co-producing.

You’ve always had strong riffs in your songs.

With the Beatles, it wasn’t just about the lyric and a melody, but their riffs. Whether it’s “Ticket to Ride,” “Day Tripper” [sings the guitar part]—hey, all the way to Neil Diamond writing “I’m a Believer” for the Monkees. These songs all have killer opening riffs.

The riff is like the musical spiritual guide. When I’m ripping on the riffs, it takes me to the emotional place of the song. I think it’s because I’m a singer. It’s also coming out of organized music in some fashion, marching in school band and listening to swing, which has a lot of riffs. I don’t read charts, but I was a drummer and there were always those kinds of parts in swing music.

A lot of the songs on Second Hand Heart include acoustic, electric, and baritone guitars. What inspired you to use that instrumentation?

To me, it’s about having an Appalachian foundation, hearing music in thirds, and hearing drones. And that comes from the Scottish, Welsh, and Irish music that, in America, evolved into commercial country music in the early 20th century ... the Carter family, the Everly Brothers. I’m talking about the border of Kentucky and Virginia, where I was born, Pikeville. It’s just there in the DNA. You hear it in the Beatles interpreting the Everly Brothers with “Love Me Do”—those droning thirds. Certain instruments just work with the baritone guitar. I can be the counterpoint to the melody in a droning fashion, while simultaneously being percussive.

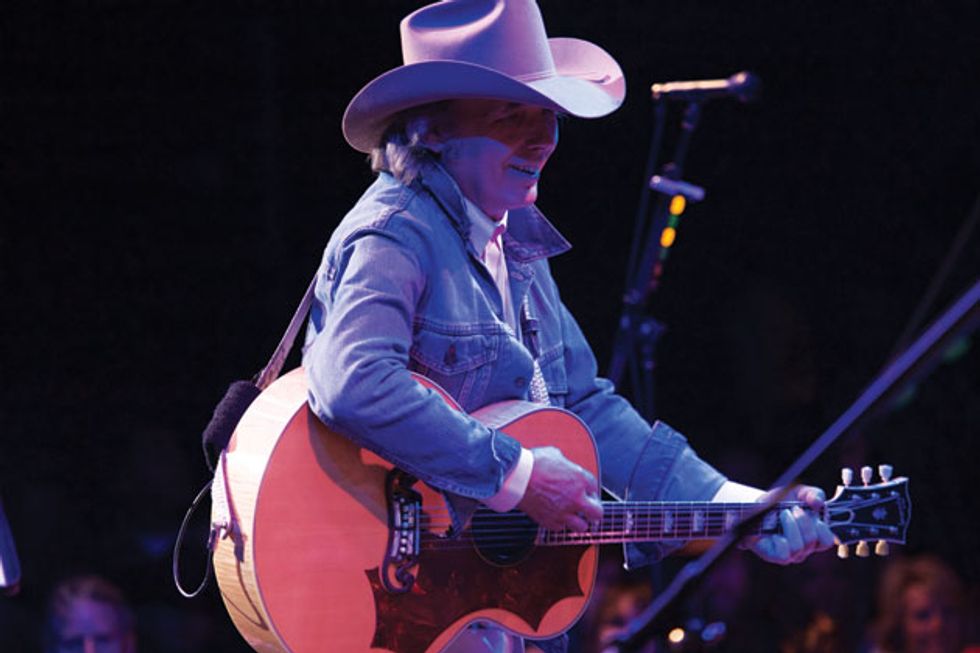

Yoakam on his playing style: “I don’t fingerpick, I flatpick. When I play bluegrass, I use crosspicking,

and I approach my songs the same way.”

Describe your songwriting process.

“In Another World” began as a little riff on my J-200 that I first captured with my iPhone and then re-recorded in the studio. I finished it as a track first and later developed it into a full-fledged song. It’s almost like being able to cowrite with myself.

Do you mean getting ideas down on tape or iPhone, and then coming back later to flesh them out?

That’s right. I began that process years ago when I was working on films in the late ’90s and knew I couldn’t set aside three months to just write songs. I was on a movie set, and I wouldn’t have time to finish a song. I found that if I captured the inspiration when it happened, I could pick it up months later with a different mindset—like it was another person contributing. It allowed me time to germinate ideas and gain objectivity through this germination.

I’d teach the band the idea I’d written and build the song out from there. And after hearing them play, I’d say, “Let’s do it differently, let me reshape that.” The album A Long Way Home had a lot of that on it.

Do you work out the arrangements ahead of time?

I’m very spontaneous. I don’t sit down and map it in any way, shape, or form. I kind of let the song lead me. I go, “let’s play this” and I’ll just start listening. If I have a bunch of guys who I’ve worked with enough onstage, who I trust to give me something that’s representative of what I’m hearing in my head, I’ll go with that.

YouTube It

In this live version of the title track from Second Hand Heart, Yoakam strums the Epiphone Casino he's paired with on the album's cover.

Most modern Nashville records sound highly produced. This record sounds polished, but also organic and live. How did you accomplish that?

Just by using tubes and knobs. To me, that’s where it really lives. It’s what I hear; it’s what I dig.

So no Auto-Tune or time correction?

To me, an effect like reverb or echo is intended to emulate something that occurs in nature when you sing in a glorious room or outside in an open area. Those systems that “correct everything” are not something of nature, so they affect the integrity of the music’s imperfections. The integrity of the imperfections—god, I want that.

I like the honesty of breath, of air, so I wouldn’t allow any compression. You can ask Chris. When we started mixing 3 Pears, I said, “You’re taking all my air away, man!” So when we started on Second Hand Heart, he just laughed and said, “More elbows and sharp, pointy edges, right?” And I told him, “Hell yeah, give me some hillbilly elbows and edges.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)