Drop a needle on a dusty old jazz or blues 78 from the ’40s, and you’ll get an inkling of how it feels to hear C.W. Stoneking for the first time. Fever visions of sweaty juke joints, late-night rent parties, and uptown nightclubs packed with lindy hoppers rise up from the black shellac grooves like heat from a Mississippi highway, invoking all the promises of mystery, romance, redemption, and revenge that have drawn blues players to the guitar for more than a century.

But this particular singer-songwriter isn’t just duplicating the sound and style of a bygone era. A small-town native of Australia’s remote Northern Territory, Stoneking grew up in a household that encouraged musical curiosity. His father’s record collection was an eclectic mix that ranged from early blues to classic ’50s gospel, inspiring the youngster to pick up a guitar, teach himself some songs, leave high school, and start busking on the streets of Sydney. Along the way, in open rebellion against the ubiquity of late-’80s pop all around him, he’d so idealized and internalized the very idea of the Blues that he stumbled onto a signature all his own.

“I was hanging with different people, and some older guys who were musicians,” Stoneking recalls in his laid-back Aussie drawl. “I gradually got deeper and deeper into blues, and it pretty much became what I was into all the time. Then there were aspects of it that I hunted down, and they led me into other types of music—things that had some parallels, like old calypso out of Trinidad, and a lot of old gospel records, too.”

He tried out the electric guitar and taught himself the banjo, but when he bought his 1931 National Duolian resonator, he had the sound—and the volume—he’d been seeking. He was barely 30 when he recorded 2005’s King Hokum, which, in songs like “Handyman Blues” and “She’s a Bread Baker,” captured the stark, haunted, and howling spirit that first drew him to the music of Charley Patton, Son House, Skip James, and so many other heroes. Three years later, he came out with Jungle Blues—a concept album that merged elements of hoodoo, vaudeville, old-time radio dramas, sea shanties, New Orleans-style ragtime, and even Appalachian bluegrass, all with a sizzling-hot horn section to top it off.

Onstage, Stoneking cuts an eccentric profile, to say the least. Clad head-to-toe in immaculate white cotton, with black-accented bowtie and greased-back hair, he resembles a young Richard Widmark right off the set of a Hollywood noir. Blues purists might be tempted to write him off as an imitator or a huckster, until it becomes apparent that this music is an integral part of who he is. And he means it, right down to his white buck shoes and his hand tattoos (on his right hand, the names of his sons, Atticus and Ishmael). Sure, there are hints of Tom Waits and even Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and Cab Calloway in some of Stoneking’s sound and theatrics, but he’s an outright original whose time is firmly rooted in the here and now.

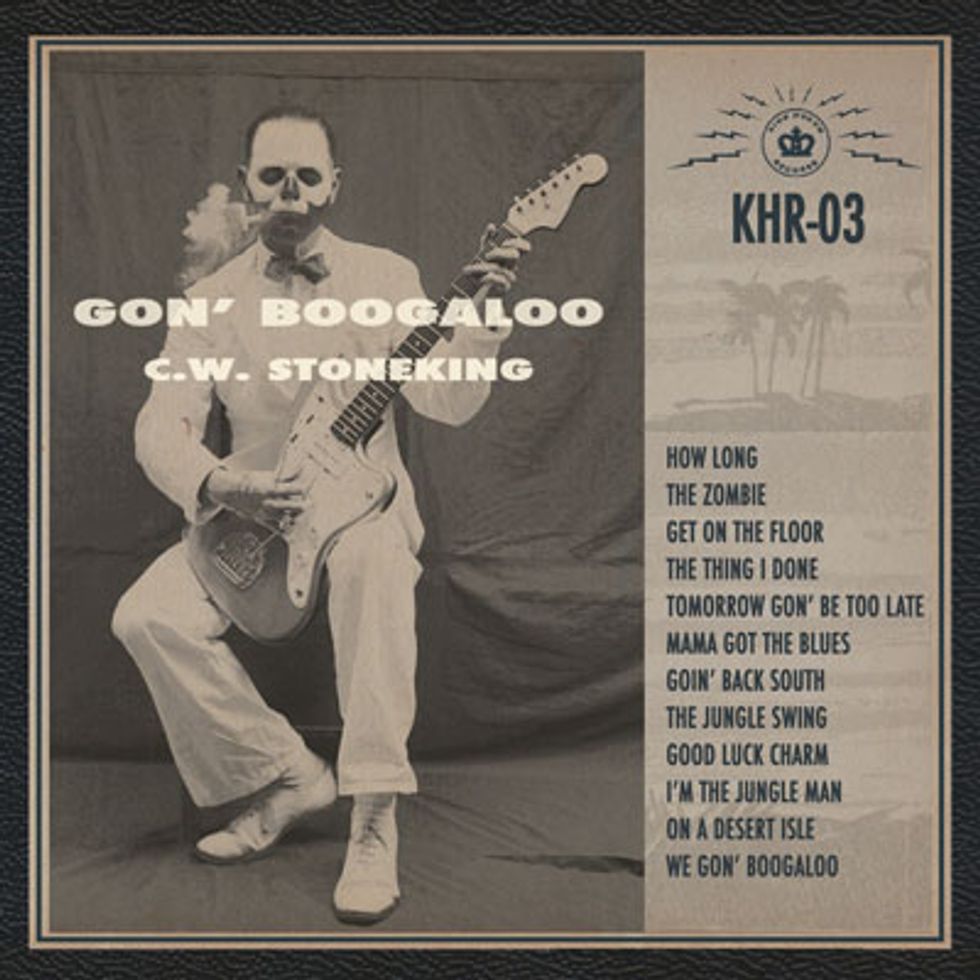

His fifth and latest album, Gon’ Boogaloo, released in 2014 in Australia and just recently in the U.S., deepens the narrative. Shortly after he recorded Jungle Blues, Stoneking decided to revamp his sound yet again—this time by plugging in. He found what he needed in the Fender American Vintage reissue of the ’65 Jazzmaster, but it took some adjustments to make it work. Stoneking had barely touched an electric guitar for more than 20 years.

“One of the hallmarks of Nationals is they have barely any sustain,” he explains. “They’re all attack and no sustain, which is what I’ve found to be challenging going through the electric, where it has much more presence. So everywhere I looked, people were telling me how Jazzmasters have no sustain, and I thought, ‘Maybe this is the guitar for me.’ They also do well with heavy-gauge strings—more to keep the vibrato system in check, so it doesn’t get too sloppy. On my National, I play .016s or so, but I don’t go quite so heavy on the electric because I do want to bend the strings. And that’s when I started to fiddle around with it.”

First, he had the guitar retrofitted with true-to-’50s-vintage pickups by Don Mare in Long Beach, California. Then he started familiarizing himself with the whammy setup, which helped him begin to simulate some of the horn parts he’d arranged for Jungle Blues. In the midst of that, he discovered a new sound that was very close to a Hawaiian slack-key guitar.

“The vibrato system actually became a big part of my playing,” he says. “Lots of stuff I make with the horns will have a slightly slurred front end on the notes. So I found it gave everything a slight bit of slurring on the front, and that seemed to take the character a little closer to what it was like being played by a horn section.”

Plugging into an old Harmony 306A combo that’s prone to overheating, as well as a custom 16-watt combo built from the guts of an antique Bell & Howell film projector, Stoneking recorded Gon’ Boogaloo in two days with a full band: bassist Andrew Scott, drummer Jacob Kinniburgh, and backing singers Vika Bull, Linda Bull, Maddy Kelly, and Memphis Kelly. Amazingly, they tracked everything live to a 2-track Ampex tape machine using only two microphones in the room—just about as lo-fi as you can possibly get in this age of laptop symphonies. The decision wasn’t entirely by choice [see “Paleo Recording: Capturing Gon’ Boogaloo’s Primitive Vibe” sidebar], but Stoneking and his bandmates made the most of the situation by trying different takes from different positions in the room—essentially using mic bleed and the room sound to their advantage.

“Some of the guys were more nervous about it than I was,” he laughs. “But I thought we could do it, and I think we pulled it off. Doing it on the fly like that, there’s always gonna be some shortcomings. If we would have had a bit more time, we probably could have ironed out some things, but I was happy enough with it, and recording was quite enjoyable.”

From the spooky dancehall jump cuts of “The Zombie” and “Get on the Floor” to the loping tiki-style strains of “On a Desert Isle” and the Carib-calypso groove on “The Thing I Done,” Gon’ Boogaloo switches gears with a mesmerizing, hypnagogic effect. And against the backdrop of Stoneking’s fascination with New Orleans voodoo tradition (on the album’s cover shot, his face is painted to resemble a sorcerer’s skull), each song comes across as exotic, mysterious and oddly psychedelic, no matter how familiar and earthbound its bluesy foundation might be.

“It’s funny, because the first time I rode through Mississippi, it didn’t look anything like the mental image I had,” Stoneking says, ruminating over the strange mosaic that inspires his music. “It looked like a cut-down jungle—this weird, hallucinated oil painting of greens. It was very fertile, and not anything like the arid, twisted, ancient landscape I thought it was, which I came to realize was completely Australian. So in some ways, I feel like I just took that sound and understood it through an Australian filter.”

One of the biggest changes for you on Gon’ Boogaloo was the switch from National resonator to Jazzmaster. Can you talk a little bit more about that transition?

Yeah, [2008’s] Jungle Blues was all National and tenor banjo. It was difficult, because I hadn’t really played the electric guitar since I was about 18, except for maybe about six months when I was, like, 21 and I played in a little local group in the country. And even after all that time, I had no desire to go back to anything like what I played before, so it was a steep learning curve all the way around. I wasn’t in any practice shape whatsoever for improvising as an instrumentalist or using moving chord voices or single-string stuff—not at all. And then just with the tonal difference of the electric guitar, I sounded very bad for probably a good year-and-a-half. I was very sloppy.

OccasionallyI’d hear a friend’s band, and I’d think maybe I should really stick with acoustic. The National just sounds good without doing anything, whereas the electric seemed like a lot of work to make it sound good. There’s a hundred bad sounds and a couple of good ones—for me, anyway. But by the same token, it was a lot of fun and very rewarding, because I was starting to really feel I’d been missing it a bit. I was working with horn players, and I would write a lot of the horn parts—and they were great improvisers as well—and here I was clunking along in the background. And I thought, “Well, you have ideas for music, so when you make it up, just find a way that you can play it, too, and then you’re speaking your own language.” I’m still pretty sloppy, but I’m getting there [laughs].

Clad head-to-toe in immaculate white and greased-back hair, Stoneking resembles a young Richard Widmark right off the set of a Hollywood noir—or a Good Humor man from The Twilight Zone.

Are there particular electric guitar players who influenced you, especially after you got back to it?

Well, when I first heard the Minton’s [Playhouse] recording of Charlie Christian playing “Swing to Bop,” I just thought it was really good. I liked the dissonance in there, but it’s still strongly rooted in blues. I didn’t really have any musical understanding of how he was achieving it, but I guess I looked into some things—like some of his diminished sounds. Then I tried to find out where you can put a diminished tonality in a song. I’d have a dominant seventh chord, and I’d start to make very basic substitutions. I did that a little with the banjo on Jungle Blues. But you know, it’s a very small handful of tricks. Basically, I’m trying to get to a very cheap rendition of what I heard on that song that was giving me a thrill [laughs].

Gospel groups were an inspiration, too, like the Sensational Nightingales, the Harmonizing Four, or the Soul Stirrers—people like that. Those were the main influences. And then again, because I was used to having horns, small bits of my songs are inspired by what I think a horn section might sound like. “Get on the Floor” has some of that in the bass and guitar, and also in some of the background singing.

C.W. Stoneking’s Gear

Guitars

Fender American Vintage ’65 Jazzmaster

1931 National Duolian Resonator

Gibson ES-330

Gretsch G6128T Duo Jet

Amps

Harmony 306A

Custom 16-watt Bell & Howell film projector amp

Lil Dawg ChocoPrince

Effects

Paul Cochrane Tim

Way Huge Aqua-Puss

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

Thomastik-Infeld Jazz Swing flatwounds (.013–.053)

Thomastik-Infeld George Benson flatwounds (.014–.055)

John Pearse Resophonic Pure Nickel Wounds (.016–.059) for G tuning

Dunlop Ultex Jazz III XL picks

Roy’s Own Nickel-Silver fingerpicks

How about your songwriting process—was it any different for this album?

I usually have my guitar in my hands when I’m doing things. I tend to get little pieces of melody and, for some reason, when it comes to the vocal line, it’s as if I’m talking in tongues in some weird way. I’ll be forming shapes of sounds with my mouth. I’m sort of just muttering, but the shapes that I form tend to have some musical correlation inherent in them. And often when I’m doing that, I have some sense of what it is I ought to be talking about. So it’s kind of frustrating, because I get these things, I can’t let go, and I’m painted into a corner. I have these half-formed words with particular vowels or consonants here or there, and I have some definition in mind, but then to put that all together—it’s weird. It’s a strange thing, but that happens a lot with me.

You mentioned “Get on the Floor,” which is such a great jam. How did that come together?

Well, I made up that chorus section and that verse, and I didn’t really have anywhere to go with it. I often have songs like that—where I have one piece, and I don’t know how to get in or out of it, or how to expand on it. I carried that around for a long time. I can’t really remember how I came up with it, but there were various little pieces of inspiration. I remember hearing Billie Holiday with Count Basie’s band doing that song “Swing, Brother, Swing”—it has this great intro where the band just explodes into the song. How “Get on the Floor” opens is a rough nod to that feeling.

Then you have “The Thing I Done,” which has a bit of an old rocksteady, reggae feel to it.

Sometimes it sounds like an old Jamaican thing to me, but, honestly, I’m really not acquainted with that music. I’ve been more into pre-’40s calypso out of Trinidad, but in the case of that song, it was much different when I was halfway through doing it. I change stuff around a lot, turn it every which way and see what else is in it, and one afternoon I just had my tape recorder rolling. I was adjusting the melody and singing it in a minor key, and then I started playing that upbeat rhythm and found a spark of electricity. Often it’s just fooling around that sometimes gives the impression that I’m more historically aware of these styles than I actually am, you know what I mean [laughs]?

How about “On a Desert Isle”? It has an implied Hawaiian slack-key sound.

That’s actually the opposite of what I’d started with, too. At first I was playing this lazy little upbeat thing, then I got rid of that and it just sounded sort of country for a long time. Then much in the way of my Jungle Blues album, I made the horn part and I started to hear little moving bits in between. This is when I was getting into using the vibrato on the guitar, and sweeping and swooshing. I started to piece together small bits of moving chords, and I just kept going. Somewhere along the line it started to feel like it could be reminiscent of a Hawaiian guitar. I wouldn’t begin to know the names of the chords, but it’s probably only got four chords in it. It’s just moving melodies, I guess, and trying to find small chord forms that carry that melody.

That comes through on “Tomorrow Gon’ Be Too Late.” Melodically, that seems like it might have come to you fully formed.

That one was much more a simple sort of thing—a little like Smiley Lewis or Fats Domino. It’s hard for me to remember now, but so many of them go through a lot of things. That was another one that, for some time, had a Caribbean flavor and then I flattened it out much more into a New Orleans R&B-sounding thing. Like I said, I fool around with them a lot before I arrive at what I decide to keep.

Can you talk about the overall aesthetic that you’ve developed on your past records, and specifically on Gon’ Boogaloo? There’s a spooky, almost Screamin’ Jay Hawkins thread that you’re following.

As far as the theme of the record, I suppose I got quite depressed with the state of the world. Sometimes you want to wallow in that, and I’m not effective in that role. It took me quite a few failed attempts to get myself straight on that understanding. Then I tried to make a party record, but carrying some of that weight. I suppose I was thinking about—I mean, you look back through history at the Christian Gnostics, when they were burning heretics, and they had this very dim view of the physical world, like they were trapped in a very imperfect creation or something. I guess there’s some of that in songs like “How Long” and “The Thing I Done.”

“Mama Got the Blues” isn’t inspired by that so much, but I can think of a hundred definitions that would suit various people around the world in different predicaments. And I guess the obvious one for the spooky thing is “The Zombie,” which is really just a weird juxtaposition between a campy sort of dance craze and the horror of pretty much … everything [laughs]. It’s just dressed up in this smiling skeleton wonky dance thing.

So it’s a weird party record, but weighted with dread?

It was a real undertaking to achieve that. I needed to be satisfied in doing something about it, but I didn’t want to be didactic. I needed a different way in, so that’s where I ended up. I guess the cover says something about that too in some way.

Well, I guess a lot of the music that I enjoy listening to, especially with a lot of Caribbean and African field recordings, has a very dry quality to it. It reminds me a lot of the music that I’d hear as a kid with old Aboriginal fellas, singing and clacking boomerangs together—this dry, clicking percussion that has a thread of that feeling. That stiches up a lot of the stuff that I’m into. It’s almost unconscious, where that took its root in me, from the experience of growing up in that place. So I think I found a sonic representation of the blues in that and, mistakenly I guess, I thought it was the same thing. And like I said, I didn’t really start to become aware of it until I drove through the [American] South for the first time. After that, suddenly it all started to piece together.

YouTube It

C.W. Stoneking demonstrates his gentle whammy-bar flourishes as he performs Gon’ Boogaloo’s “On a Desert Isle” solo at the Monk Club in Rome last year.

Factoid: Stoneking’s new album was recorded live and direct to a 1/4" tape machine using only two microphones.

Paleo Recording: Capturing Gon’ Boogaloo’s Primitive Vibe

With his band only available for two days to record the 12 songs on Gon’ Boogaloo, C.W. Stoneking already had his work cut out for him. So when he walked into Sound Recordings Studios (just outside Melbourne, where he now lives) and was told by engineer Alex Bennett that the 4-track machine they’d intended to use had broken down the day before, he feared the sessions might be jinxed.“First time I met him,” Stoneking chuckles, “he had an 8-track machine there that he’d already told me was a piece of junk, but we started plugging into it anyway. We were checking out mics, and I was having difficulty getting a guitar sound that I liked with a close mic on the cabinet. I kept moving it further away until it was so far across the room, I was like, ‘Well, how much bleed am I getting into my vocal mic?’”

Stoneking’s Jazzmaster actually sounded better bleeding into his old RCA 77-DX ribbon microphone—and, he discovered, so did Andrew Scott’s double bass. By then, they were down to just a couple of overhead mics on the drums when Bennett suggested they could switch the setup over to a more reliable Ampex 351 1/4"-tape 2-track machine.

“We did a pass of a song and it sounded a million times better,” Stoneking notes. “It was a pretty minimal song—one of the ballads—but I was like, ‘Okay, let’s just do it like this and we’ll figure it out as we go.’ So we pretty much built the band around the RCA, and I sang into another microphone. [Author’s note: The vocal mic was a vintage, Soviet-made tube condenser, much like those used by radio announcers.] We’d do a pass of each tune and have a listen back, and then just position everybody. The amps and the drum set stayed where they were, but for songs with acoustic bass, sometimes we’d have to reposition him or the singers to get the right mix.”

As primitive as it sounds, the setup turned out to be crucial to the overall atmosphere of Gon’ Boogaloo. The only way to “mix” was to do it on the fly, using mic position and the room itself: with the guitar, for example, sounding overdriven and upfront on “The Jungle Swing,” or with the background singers clear and present on “Good Luck Charm” and more submerged into the rhythm section on “Get on the Floor.” And then, of course, because overdubs weren’t an option, it meant going all-in and committing to each performance.

“I think the energy takes over,” Stoneking says, “but in terms of the old sound, I think it works because we kept it pure. For instance, the old tube condenser mic that I sang into would overdrive when I shouted into it, like some of Little Richard’s rock ’n’ roll records. I was like, ‘Yeah, let’s keep it. That sounds pretty good.’ And then I guess there’s the tape compression, but we didn’t add anything, really, to the sound. It was very pure—just performing straight to tape. Bam, that’s it!”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.