“They’re sort of floating around out there, and we don’t even know where they’re coming from or how far they are or what’s going on.” Bill Frisell is talking about melodies and stars, but what he’s saying illustrates a lot about his sound. From the tones he conjures out of his guitar to his improvisational vocabulary, Frisell draws from ideas that seem to be floating around in the musical cosmos. At any moment, he can sound equally referential to early rock ’n’ roll, classic country, jazz of all eras, and the cutting edge of experimentalism, but he always sounds completely personal and instantly identifiable.

Frisell thrives on fitting his sound into unique musical situations, which can range from playing alongside jazz saxophonist Charles Lloyd to the Grateful Dead’s Phil Lesh to doom-metal lords Earth. Variety seems to dictate many of the guitarist’s artistic choices, and his discography is full of a wide range of highly focused projects, from his early avant-garde-quartet releases on ECM Records to country and bluegrass-tinged projects like Nashville and The Willies to his world-music album The Intercontinentals or his recent take on classic motion picture themes, When You Wish Upon a Star.

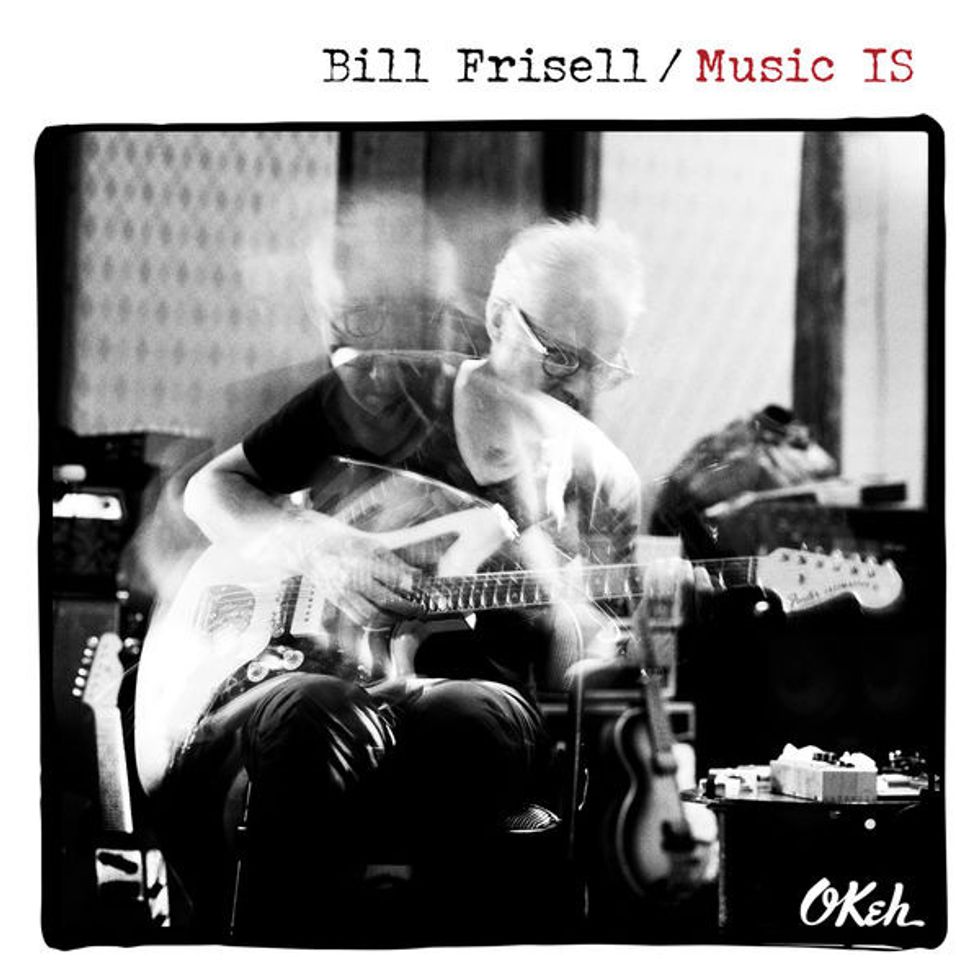

For his newest release, Music IS, Frisell has chosen to make a return to solo guitar. He’s explored solo music throughout his recording career, starting with the four solo pieces on his debut album, 1983’s In Line. He returned to the idea on 2000’s Ghost Town, which featured layers of guitars and bass ruminating on dark Americana themes, and then took a much different approach on 2013’s Silent Comedy, freely improvising in the studio.

Music IS feels like a culmination of those previous efforts. While many of the pieces feature carefully layered guitar parts, there is an openness to Frisell's playing and choice of tone that feels live and spontaneous. Despite referring to solo playing as an “ongoing challenge,” Frisell sounds at home on the album’s 15 tracks—some of which are new compositions and many of which are new versions of tunes that he’s recorded in other formats on previous albums. “It was like seeing it as if someone else had written it, so I was almost learning it for the first time all over again, or seeing things that I never knew were there,” he told Premier Guitar during our phone interview, explaining why the tunes on his new album sound as fresh as ever.

Music IS is warm and welcoming, much like the man himself, and Frisell has plenty of stories to share. We discussed his ideas about playing solo, why it was time for another solo guitar outing, the cool things about getting older, finding guitars with a story, and more.

This is your third all-solo album and they are all such different recordings. What was your path to making these albums and why was it time for a new one?

Playing by myself has forever been this ongoing challenge. Even my first album on ECM [1983's In Line] started as a solo record, but then I wasn’t quite ready for it and Arild Andersen ended up playing bass on some of it. From when I first picked up a guitar, what I loved about it was the way I interacted with people. That was what my social life was: getting together with people and playing. I’m talking about the early ’60s. I know there’s the whole singer-songwriter, one-guy troubadour thing, but I was never that. For me it was always about being in a band. Seeing the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show or, even before that, the Ventures and all that stuff, it was a bunch of guys getting together with their guitars and hanging out. Not just the guitar, but music in general is about this community and being together and having a conversation.

So, way, way back, it was always in my mind that I wanted to be able to play by myself. At first I was so scared to do it. I felt like, I’ve gotta try to do this. In the early ’80s, I remember the very first time I tried to do a solo gig. It was in this tiny little loft place in Boston and there had to be five people there: my wife and my friend and a couple other stragglers. I was just so terrified to sit there and try to play alone. It was like torture or something. I swore I would never do it again. But it was just this challenge. I felt like, I’m supposed to be a musician. I ought to be able to sit there and play something. So, I tried again a year later and it was still hard, but I got through it a little bit better and I kept trying to do it and finally something broke through. Now I’m at a point where my confidence is up to where I can at least get through it without having a nervous breakdown. There’s also an aspect to it that’s really great. The kind of freedom you have playing alone is amazing, too. Whatever the mood or whatever you’re thinking about, you can just go off in whatever direction you want.

TIDBIT: To prep for recording Music IS, Bill Frisell played an off-the-cuff, six-night solo stint at the Stone in Manhattan. “I just brought in a pile of music and every night I’d try to play stuff that either I hadn’t played for a long time or stuff that was brand new,” he says.

It’s also my nature. I flunked speech class in school. Just to be alone and standing up in front of people and making statements … even if I know what I’m talking about, I’ve never been comfortable with that. Playing alone, it’s a similar thing, where you play an idea and it goes out there and what are you going to do next? If nothing comes back at you, it’s like there’s this space that you have to get comfortable with, and it’s just you generating all the information. It’s been this long, ongoing process of me getting more and more comfortable.

There’s been a kind of narrative through your solo work.

It’s interesting to have these markers along the way, like from the first ECM record, and then there was Ghost Town. Silent Comedy. [For Music IS] there was absolutely no thought. I didn’t prepare. I didn’t do anything. I just walked in there and “bam,” in a couple hours the whole thing was done and that was a whole other way of thinking about it. It was completely improvised. I realize I’ve made some progress in my comfort level. I played some tunes that I’d written many years ago, but I hadn’t played them in a really, really long time, so it was far out to look at my own music. There are certain parts of getting older that are cool—where you can see that you actually have learned something.

You’ve been revisiting your own tunes throughout your career—re-arranging and re-recording songs that were on earlier albums using different groups. How did you determine which songs you would revisit this time?

I wasn’t conscious of it. The preparation was that, prior to the recording, I played six nights at the Stone. [Editor’s note: John Zorn’s venue in Manhattan.] I was trying to keep myself in this state of not being sure what I was gonna do. I didn’t play stuff that I knew was gonna work when I went into the Stone. I just brought in a pile of music and every night I’d try to play stuff that either I hadn’t played for a long time or stuff that was brand new. And when I went to the studio, I did the same thing. I didn’t wanna have it all mapped out beforehand.

I don’t remember even what we started with or what caused the decision to make the first choice, but that determined what was gonna happen next—even the guitar. I wanted to stay in that kind of spontaneous, in-the-moment state for the whole recording. However, I would decide to orchestrate a particular piece, or whether it was just naked guitar or a bunch of guitar or some loops or whatever. That all just happened right as I was doing it and then we mixed it as I was doing it, too. So, each piece was finished before I went on to the next one.

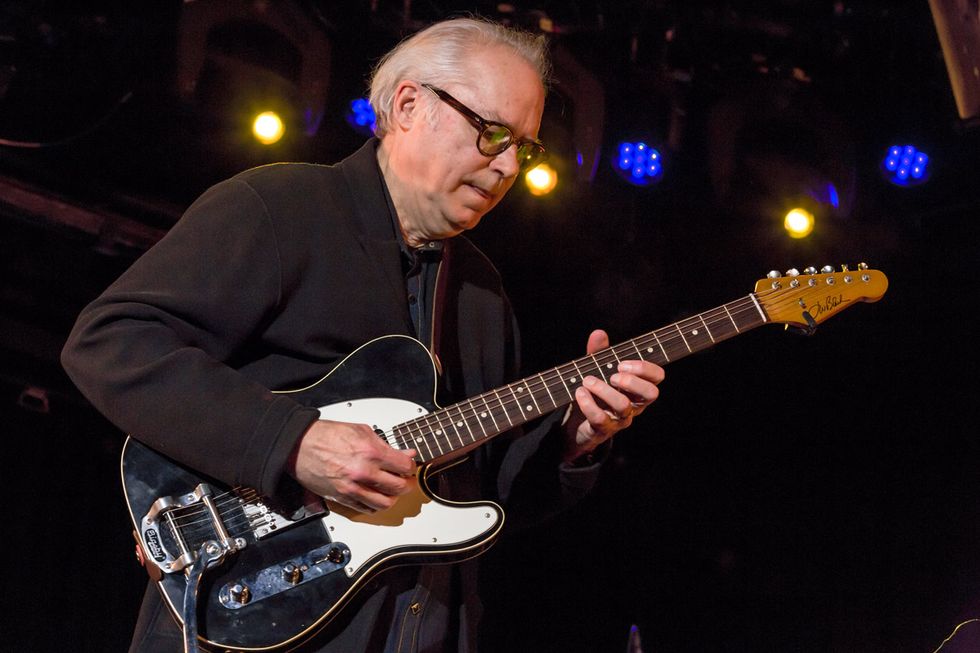

When Bill Frisell travels, he typically rolls with a single T-style instrument. Here he’s playing one of his J.W. Black guitars at New York City’s Le Poisson Rouge on March 10, 2017. Photo by Scott Friedlander

So, it was the same approach to playing a live set of music?

Yeah, because now, when I play a solo gig, I don’t think about it at all, really. Sometimes I have no idea even seconds before I start playing, I’ll just play a note and hopefully that’ll lead me to a song or something and it just starts going from there. This was definitely more controlled than that, but it’s basically the same attitude.

Also, the way we set up the room was so cool. I had a number of guitars and I had a few amps. We set it up so I could move quickly from one to another, or I could even grab an acoustic guitar while there was something happening with the electric guitar. That was really cool: to get that all straight at the beginning so that, whatever came into my mind, I could just go there without moving things around. Once we got it set up, it was like being in this amazing playground.

On Music IS, the songs “Pretty Stars” and “Made to Shine” are versions of “Pretty Flowers Were Made for Blooming” and “Pretty Stars Were Made to Shine” from Blues Dream,and they open and close this album. Each of those songs goes in a different direction, adding new material and new ideas to the original versions. When I first heard this, I thought maybe you used Blues Dream as an intentional theme, but now that I hear about your process, I’m curious how those songs became such an integral part of Music IS?

When we had all the pieces done, we just shuffled them all around and found an order, tried to make a story out of it or something. It seemed like a good way to start it, and then somehow because it started that way it seemed like a good way to end it, too.

just incredible to feel.”

There’s something I should say about that song. I don’t know if I would say it’s disturbing, but the thing about writing music is, the older I get, it gets weirder and weirder with my memory and where a melody is coming from. I sit there and I write all this stuff and I’m not sure where it’s coming from. It’s like; “It has to be something that I heard before? Am I remembering it? Or am I making it up?”

During that week at the Stone, I played that “Pretty Stars” thing. This guy, one night, said, “Oh yeah, I really like your version of ‘Jesse James.’” And I’m thinking, “What’re you talking about? Because I thought I had written the song. He said, “I have a version of Ry Cooder doing that song, ‘Jesse James’.” And I listened to it and I thought, “Oh my god, it’s the same melody that I thought I wrote.” Then I looked at it further and I realized it’s this old folk song. The Kingston Trio did it. I must have heard it when I was 5 years old or something, but when I wrote it down, what I wrote down was slightly different.

I already called the thing “Pretty Stars Were Made to Shine” long ago, and then I started thinking about stars. You know, we’re all looking up at these stars and everybody sees them. They’re up there for everybody. They come in and out, and one day you see some and another day you see others. It’s kind of like the way those melodies are. I guess I stole that or it was somewhere in my memory: this old traditional song that I wrote down, or some variation on it. You stick with it for a little while, and then it starts to sprout other branches. That’s what’s really far out! Because if you keep writing or you keep playing, these variations start happening and it keeps growing.

Guitars

J.W. Black T-style

Late-1950s Gretsch Anniversary

1940s Gibson J-45

1950s Gibson ES-125

1966 Fender Jazzmaster

Amps

Gibson Explorer

Carr Mercury

Effects

Ibanez Tube Screamer

Catalinbread Katzenkönig

Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler

ZVEX Ringtone

Strymon Flint

Lehle Little Dual

Strings and Picks

D’Addario Chromes strings (.011–.048)

D’Addario EXL115 strings (.011–.049)

Dunlop 412P .88 mm Tortex Sharp picks

There’s a video for an alternate take of your tune “Rambler,” where you’re playing a Gretsch. Did you use some different guitars on this album than you’ve used in the past?

Yeah, that was kind of a luxury this time, because many times, when I’m traveling, I’m just going around with one instrument. I have a bunch of guitars at home and I don’t get to play ’em so much when I’m on the road.

When I started to plan the record, I didn’t even realize I was gonna end up moving from Seattle to New York. When I moved away from Seattle, I had a rental car and I put a bunch of guitars in my car and I drove down to Portland and I left them at the studio there. So, when I went back in August to record, I had a bunch of stuff, which was so cool.

What guitars did you have with you?

I had this old ES-125 that I used a lot on this record. Just one P-90 pickup in it, from the ’50s. I also had a ’66 Jazzmaster that I recently got and used on a bunch of stuff. When I’m traveling, I’m basically carrying some kind of Telecaster with me, so I also had this J.W. Black T-type guitar. And I had this incredible Gibson J-45 from the 1940s. It’s one of those banner-year guitars. That was actually a gift. Just within the last couple years, I guess, I got that guitar and I was thrilled to record with that.

I know there’s an old Gibson you own that used to belong to your teacher, Dale Bruning. That’s not that guitar, right?

Oh, no, I didn’t have that on this recording. I still can’t even believe that happened—this guitar that I got from my teacher in Denver in the ’60s that was my main guitar. It’s an ES-175, but it was a custom that he ordered, I guess it was in 1967 or ’68, and then it was 1970 when I bought it from him. I probably spent more time with that one guitar than any guitar in my life. I ended up selling it and regretting it and then I could never find it. I sold it in Boston in 1978 and then it showed up in Seattle in 2015. I wish I knew the story of where it had been. How did it make it there? It was unbelievable.

Check out this Bill Frisell-inspired lesson.

This photo illustrates Bill Frisell’s daily ritual: wake up, have coffee, write music. “At this point, there are piles and piles and piles of single pages of staff paper filled with his graceful script,” reads the press release for his new album, Music IS. Photo by Monica Jane Frisell

What is that Gretsch?

I’ve had it for a long, long time. It’s an Anniversary from the late ’50s and it’s been through a lot. It was single-pickup when I got it and I added the second pickup and a Bigsby to it, and I changed the bridge. It’s been refretted. They had to reglue the fingerboard onto it and all that stuff. It’s been really fixed up.

There’s a guy, John Stewart, who deals in mostly archtop guitars, and there was a time when I had thought to sell this guitar. Then I changed my mind, but he had a picture of it on his website. Some guy called him and it turns out he was the original owner of this guitar. He was a professional guitar player in the ’50s and ’60s, in a country band. There’s a publicity picture of him with a cowboy hat and all that, playing this guitar. The reason he recognized it is because he had stickers all over it. They look like things that my grandmother would have put on her bread box or something—these little flower stickers that are all around where the knobs are. They’ve sort of melted into the lacquer of the guitar so you can’t take them off.

How about the amps and effects you used on this record?

At home, I’ve got this 1x10 Gibson amp. I think it says “Explorer” on it—just volume, tone, and tremolo. That’s one of my favorite amps. Tucker Martine at the studio [Editor’s note: Martine engineered the album at his Flora Recording & Playback in Portland.] ended up buying an amp just like it, so I had that and I used a Carr Mercury, which Tucker has at the studio and I like a lot. Then there was one other amp—it might have been a Princeton—that I sometimes used.

And then the effects: I always used the Line 6 pedal: the DL4. I used an Ibanez Tube Screamer and I used a Catalinbread Katzenkönig. It’s like a real intense kind of fuzz tone thing, and then I used a ZVEX Ringtone. Some of the oddball stuff came out of that. You can get almost a sort of sequencer-like thing. And then a Strymon Flint reverb and tremolo. I always have that around these days. One thing that’s been great: this Lehle—it’s a Little Dual—because I use two amps a lot and it’s made for switching between amps.

The track “Think About It” was recorded through a piano. Was that your idea?

Oh yeah. We just stuck the amp right in the back of the strings of a piano. I didn’t use any real reverb or anything. It’s just the pedal is being held down and the strings are ringing. I’m playing pretty loud into the strings of the piano. Later I found out that piano was owned by Richard Manuel from the Band, so it sort of took on this whole other vibe thing with thinking of all those songs he played or wrote on that.

You seem to attract instruments that are part of a cycle.

I love that. There really is something about when you play a guitar that someone else has put a lot of time into. Recently, I got to play one of Tal Farlow’s guitars. It was his main guitar. This was at Rudy’s Music in New York, and they had a few of Tal Farlow’s guitars. It was just incredible—like I could almost feel the pathways of where his fingers had been on that. Suddenly, I could play these chords that I’d never been able to play before. Because he had these really long fingers. I started playing the guitar and I was like, wow, my fingers are kind of ... I don’t know—a lot goes on with these instruments.

Melody shines brightly throughout this improvisation, which is clean and un-effected compared to the version of “Rambler” on the Music IS album. Frisell reworks the tune with every pass on his ’50s Gretsch Anniversary model, allowing the Filter’Tron pickups to work articulate magic.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.