Playing guitar is an exercise in discovery. The more you do it, presumably, the better you get, and the more you learn about the instrument’s possibilities coupled with your own potential to advance. People often travel repeatedly to the same places. Not out of lack of imagination, but as an extension of the discovery process. Once you’ve seen the Eiffel Tower or Grand Canyon, you can go back and discover a nice bistro on a side street you’d never noticed, or a trail that may have been hidden previously. With that in mind, here’s a question that deserves repeated exploration: How do preamps and power amps—and rack systems in general—differ in dynamic behavior from self-contained guitar amps? And why? This was a hot topic during the heyday of rack systems. Technology has come a long way since then, so it’s worth revisiting the subject.

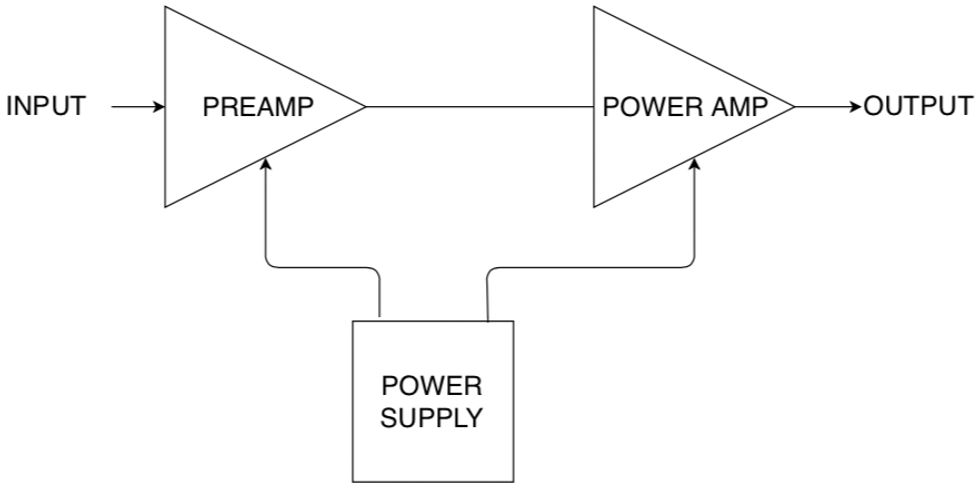

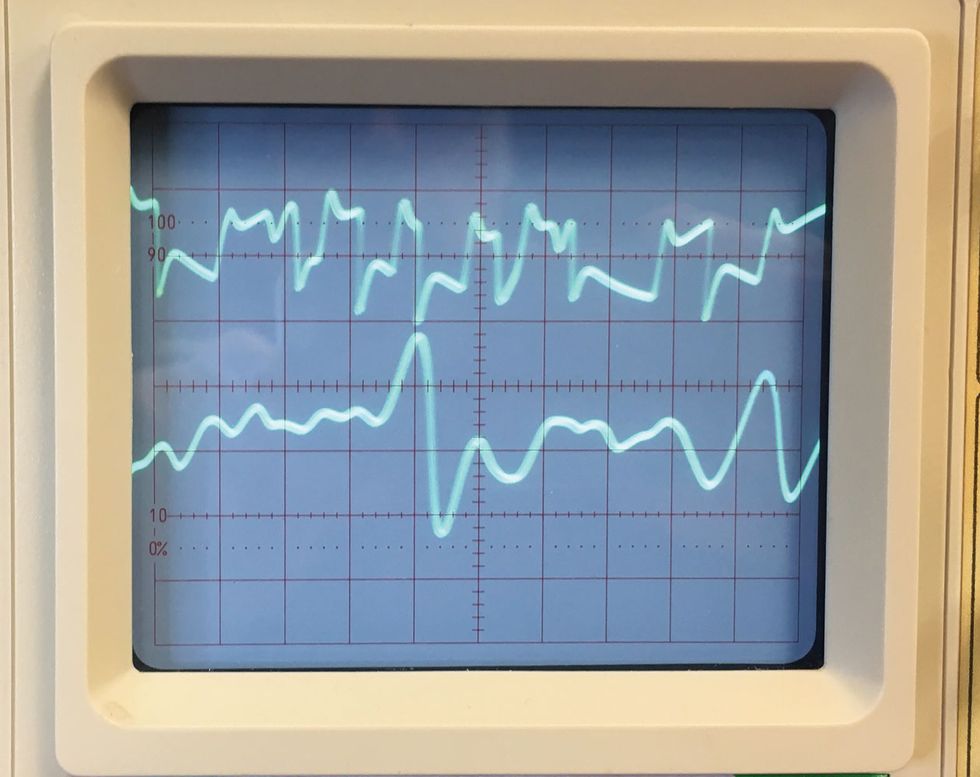

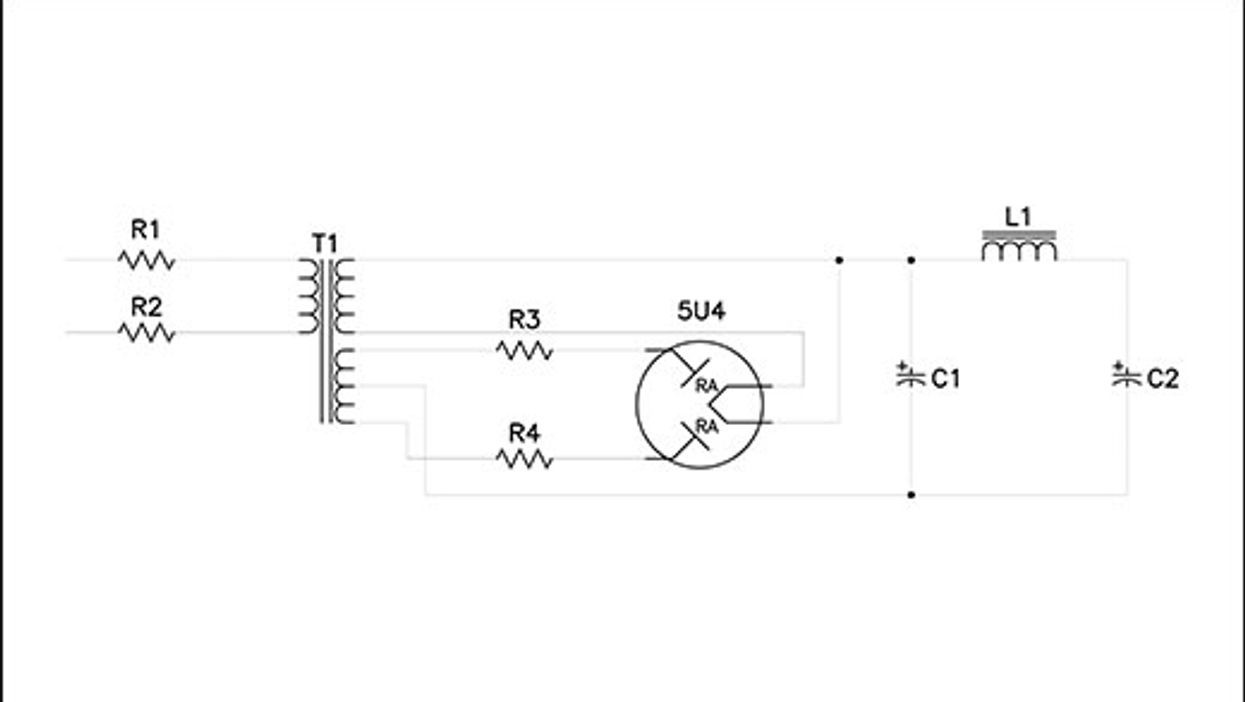

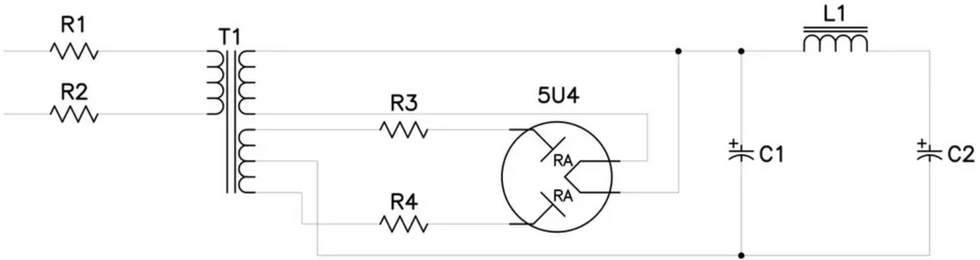

We’ve discussed the dynamic loop created by pick attack and playing volume, and how current demand from the power amp stage affects the preamp stage [“The Big Bang” and “The Sonic Legacy of Tube Amplification”]. To recap, a self-contained amplifier, consisting of a preamp stage and a power amp stage, gets its operating current from a common power supply (Fig. 1). When you play clean and at low volume, both the preamp and power amp benefit from a healthy reserve of available current. Once the volume goes up and pick attack intensifies, the power amp’s demand on the power supply increases exponentially, leaving whatever crumbs are left to the preamp. Now, to be fair, an amplifier’s power supply is normally designed to deliver sufficient juice to the preamp even under demanding conditions. But the truth is, a lot of what differentiates amplifier personality can be directly traced to the designer’s ideas about how much preamp voltage variability is acceptable or even desirable. This gives rise to terms ranging from “spongy” and “forgiving” to “dry” and “stiff,” and—sin of all sins—“unforgiving.”

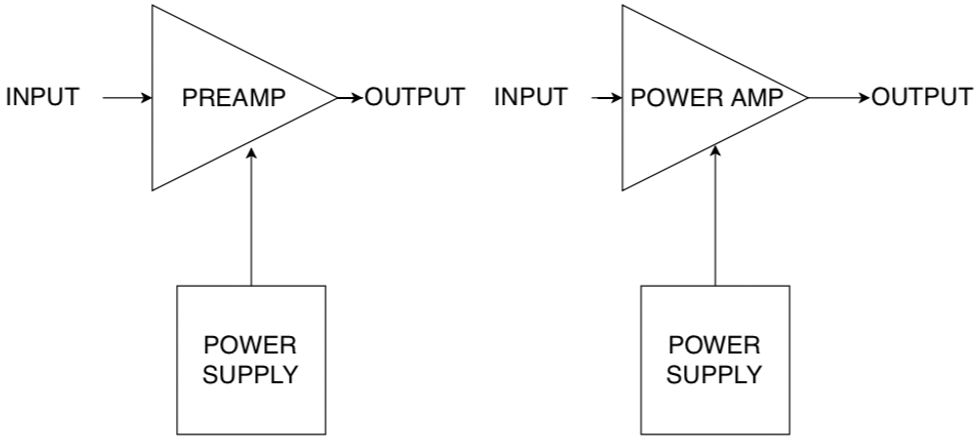

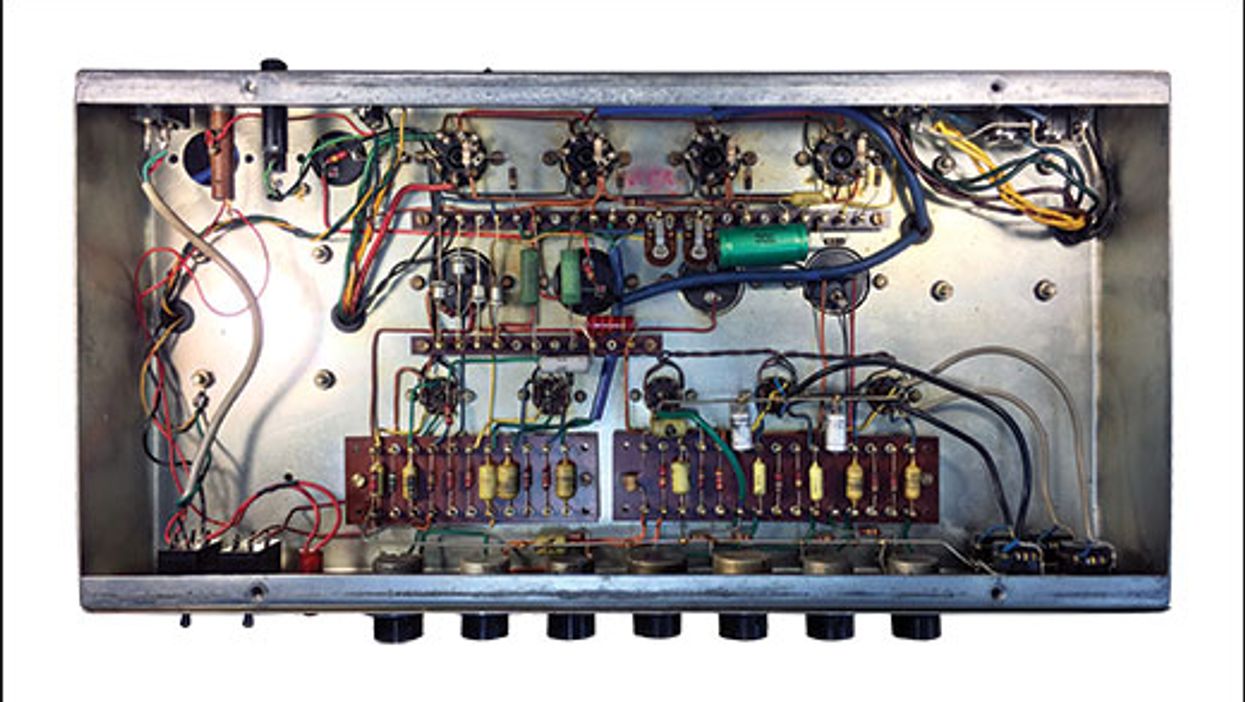

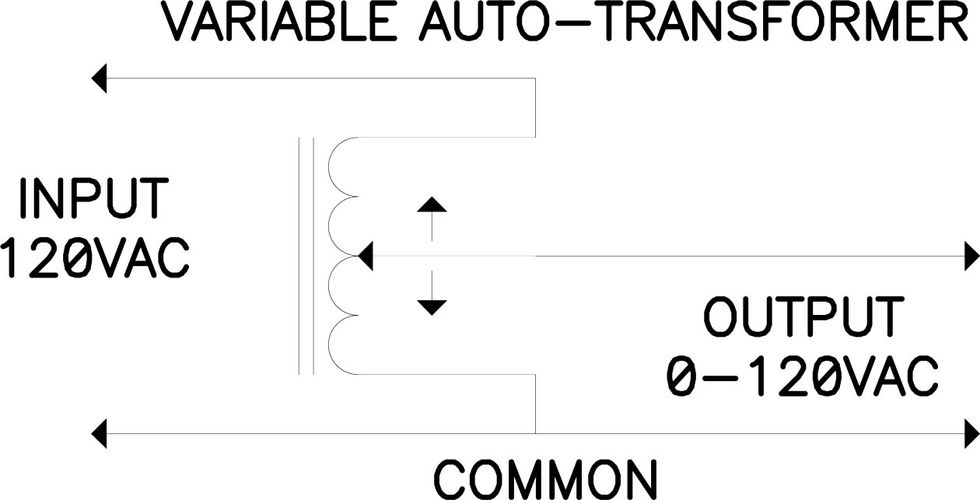

So, let’s look at the rackmount preamp and power amp. In a system made up of separate components, the defining feature is that they each have their own dedicated power supply (Fig. 2). Right off the bat, this precludes that beast of a power amp from hogging all the juice to the preamp. The first thing we discover in playing this rig is that the dynamic feel is noticeably stiffer and absent some familiar gooeyness and bloom. In early rack systems, getting a group of components to feel like playing a normal amp usually took a back seat to the benefits of extensive signal switching and processing. My personal feeling was, and still is, that a well-executed rack system demands a power amp with a good range of control over frequency response and dynamic feel. Most of the time power output is less important than the kind of tube character you like, especially in a stereo power amp. I bring up stereo because this is a feature of rack power amps that always gets overlooked.

In a stereo power amp, the power supply is usually common to both channels, and therefore has to be sufficient to provide full output for them. It rarely occurs to players that if you only use one 50-watt channel of a stereo 100-watt power amp, you still have a 100-watt energy reservoir on tap. Naturally, that’s going to feel extra stiff compared to a single power-amp stage of a 50-watt head. If you expect to arrive at reliable conclusions about different power amps in A/B comparison tests, it’s important to run both channels to really understand what you’re hearing.

Fig. 2

Some stereo power amps use a single 12AX7 for the input stage of both channels, while others have a separate tube for each channel. The reason this is important is not immediately obvious, but it certainly bears scrutiny. Crosstalk, or signal bleeding from channel A into channel B, often occurs in a power amp with non-isolated triodes, as opposed to isolated triodes. If you use a stereo FX processor to A/B test each design type with both channels operating, the amp with non-isolated triodes will sound practically mono due to signal bleed at the first preamp stage, while the amp with isolated triodes will deliver a markedly superior stereo image. If you compare these two design styles side by side, one channel at a time, you’d totally miss the significance of isolated triodes on the input stages.

Those two simple subjects—power supply capacity and crosstalk—play a major role in the difference between rack gear and self-contained amps. Here, a seemingly benign question offers an opportunity to understand nuances of amplifier design that are rarely discussed.