Steve Marion might not be a particularly well-known figure amongst the mainstream of guitar music cognoscenti (yet, at least), but there’s a distinct possibility you’ve heard his playing before. Marion releases his own guitar-focused instrumental albums under the moniker Delicate Steve, but has worn a wide variety of hats over the years, working as a session guitarist, producer, and songwriter with a cavalcade of hip, adventurous, and downright legendary artists since initially gaining notoriety for his intriguing guitarwork within New York City’s ever-eclectic music scene.

Marion’s first two albums as Delicate Steve (2011’s Wondervisions and 2012’s Positive Force) were released on David Byrne’s wildly diverse Luaka Bop label, and those offerings earmarked the New Jersey-bred guitarist as a standout in a scene that really embraced musicians who reveled in abnormal styles or framed their work in off-kilter ways, but came from a technically proficient place. In many ways, Brooklyn’s music scene in the mid-aughts mirrored the freewheeling, intellectual, and anti-establishment spirit of Manhattan’s ’80s No Wave movement—which famously influenced Sonic Youth—but with a much less sonically combative attitude.

Watch the animated official video for “Till I Burn Up,” the title track from Delicate Steve’s latest album.

So, what exactly is it about Delicate Steve’s music and Steve Marion’s guitar playing that’s not only allowed him to build one of the most impressive and varied resumes of anyone working today, but also garner legitimately strong reviews—and remember, these are instrumental guitar records—from famously cutthroat outlets like Pitchfork? Steve Marion’s approach to the guitar shirks almost all of the clichés guitarists typically love about the instrument.

The latest Delicate Steve album, Till I Burn Up,is a perfect point of entry for those uninitiated to the cult of Steve. On his new LP, Marion has embraced what he describes as his “unhinged” side and found the confidence to allow Delicate Steve—formerly his sole creative outlet—to become a space for truly unfiltered self-expression. It’s undoubtedly a rock ’n’ roll album, but one that swings with the swagger of contemporary pop hits, the square-wave intrigue of classic prog, and the bubbly ambiance of ’70s African rarities. There are moody moments (“Ghost,” “We Ride on Black Wings”), but the record doesn’t take itself too seriously. Taking influence from albums that had flopped upon release, but would go on to become well-respected and influential (like Dr. John’s Gris-Gris and some of Iggy Pop’s weirdest work), Till I Burn Up seems like a raging party attended by each of Marion’s many musical personalities—none of which rely too much on classic guitar tropes, but remarkably never come off like they’re trying particularly hard to be futuristic.

Part of that trick is that for many years now, Marion’s key influence has been the work of soul singers rather than other guitarists, and he’s worked hard to posture his guitar as a kind of second voice. Additionally, while Marion is an extremely capable player, he avoids histrionic flash altogether, which lends his music an air of playfulness and means there’s never a moment on Till I Burn Up that sounds like it’s got something to prove.

Whether adopting the timbre of a synth or copping the vibe of a distorted and auto-tuned pop vocal, Marion’s guitar is always about conveying a vibe and a melody, and his slide guitar in particular—which is worlds away from anything one might describe as bluesy—has a distinctly human quality, but is very much its own thing, much like how George Harrison created his own inimitable vocabulary as a bottleneck player.

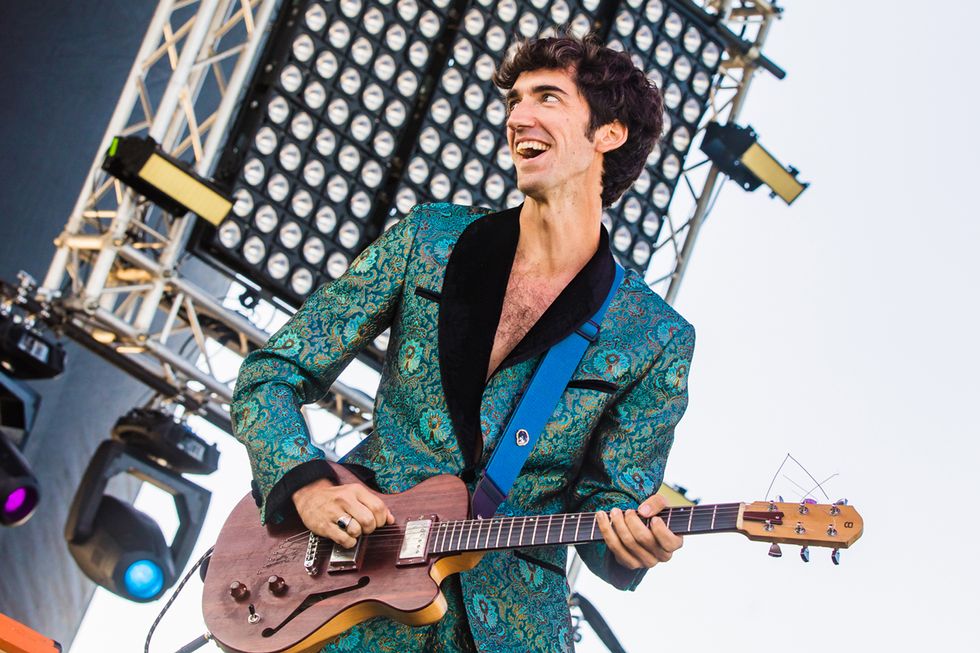

Premier Guitar spoke with Marion as he was knee deep in a tour to promote Till I Burn Up. The jovial anti-guitar hero from Jersey opened up about his new record, his background and philosophy as a player, his motivation when it comes to Delicate Steve, and even shared the tale of his recording session with Paul Simon.

As someone who has played on and produced many records by other artists, what’s your motivation when it comes to the instrumental guitar stuff, particularly on Till I Burn Up?

I feel happy with where I am in my career and I say “yes” to working on almost anything, if it seems even remotely interesting, because I like to work. Everything that’s happened for me so far has been through friends or friends-of-friends, so it doesn’t necessarily feel like I’m exactly in-demand so much. I feel content with that, but it doesn’t feel like my playing is the thing everyone needs on their track.

Until a couple of years ago, my whole identity as a musician was just a guy making instrumental guitar records. The only way I could export my creativity was into Delicate Steve, but having more outlets has made this a creative place where I can actually be a bit more unhinged. That’s a recent development, and the first three studio albums, when Delicate Steve was really my only outlet, the music was maybe a little less playful because of that.

On his new album, Till I Burn Up, Marion played just one guitar—a ’66 Gibson Melody Maker SG equipped with PAF humbuckers.

Till I Burn Up is a bit looser than your past albums and has a fuzzy layer around the edges in a fun way.

I was really paying attention to artists I like, like Iggy Pop or Dr. John—artists I was casually getting back into at the time. Dr. John’s debut album [Gris-Gris] was a critical and commercial failure when it came out, but it’s now on Rolling Stone’s 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list. It’s kind of funny how that works. Looking at that phenomenon, how weirder records are initially received versus how they’re remembered gave me some inspiration to be more free in my own music.

I’m one of the only “indie” artist making instrumental guitar records that’s even sort of on the radar, so it does take a lot of work to get people to pay attention to it. Until this last record, I was trying hard to produce something that was really accessible, but this is the first record where I’ve embraced feeling like my music doesn’t really fit in. There’s not a lot out there that excites me in a way I want to be a part of, so this record is where I finally said “fuck it” and decided to pave my own path.

I hear that come through in some of the more aggressive, synth-like fuzz tones you used on songs like “Freedom” and out-there moments like the kitschy space boogie of “Rubberneck.”

It’s so boring to see artists continually put out what they’re expected to put out and pander to this really tiny indie world—which I guess I’m a part of—and not push themselves creatively. I’m being really negative right now, but it just seems like everyone is trying to fit into whatever box they’re already in, whether they’re a punk-rock person or an indie or electronic musician.

I definitely want to push the box I’m supposed to be in. I like to play with elements of experimental music because it’s not really expected of me or of instrumental guitar records. Everyone thinks my guitars sound like synths, but I was thinking more along the lines of Kanye West’s vocals, where it’s a distorted and Auto-Tuned room mic, like on My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. My inspiration was trying to channel a reverent second take on that.

That’s unexpected, but you’ve done a session for a Kanye West record, right?

Kanye sampled one of my songs. I know a producer brought it in, Boogz Da Beast from Chicago, who is one of Kanye’s old friends and apparently a big Delicate Steve fan. There’s only a little snippet of the track out and while I haven’t heard the whole song yet, my old record label says it’s really cool and Kanye actually sings my guitar part. That’s something I’ll always be proud of! I think Kanye West is a creative genius and he’s a big influence on me, so knowing that he was inspired to turn something from my music into a song ... well, that’s just so cool to me.

As a guitarist, Marion is inspired more by singers than other 6-stringers. “Mostly soul singers like Nina Simone, Michael Jackson, Stevie Wonder, Sam Cooke, and Otis Redding,” he says. “When those singers hit one or two notes in interesting ways—where they put those notes rhythmically against everything else in the song—it’s so anti-guitar wankery to me and so much more compelling than a lot of what guitarists do.” Photo by Debi Del Grande

Your guitar influences are pretty hard to pinpoint from the music you make. Who do you look to for inspiration these days?

I grew up admiring many guitar players, but I became more fascinated with singers. That’s really where my Delicate Steve guitar style took shape. Mostly soul singers like Nina Simone, Michael Jackson, Stevie Wonder, Sam Cooke, and Otis Redding. Their vibratos, melodic sensibilities, and dynamics informed where I’m coming from. When those singers hit one or two notes in interesting ways—where they put those notes rhythmically against everything else in the song—it’s so anti-guitar-wankery to me and so much more compelling than a lot of what guitarists do.

It seems like many guitarists who do well are carbon copies of other guys from the past. I don’t think that originality is truly celebrated, especially in 2019. I can mimic Jimmy Page’s playing pretty easily because I grew up loving it, but I would never want to do that, because it’s already been done.

You’ve produced many albums for other musicians over the years. How has your experience as a producer, especially recently, changed your approach to Delicate Steve and guitar in general?

Producing and arranging has always been where I’ve come from. I don’t think that’s changed much recently, but I’m getting the opportunity to do that work more, and it’s something I’m really interested in. I like to approach my guitar playing more as a producer than an instrumentalist, and it has been really fun to work on records like the Amen Dunes album with Damon McMahon, who I really admire. We made that record at Electric Lady. Working in this studio that’s known for all of these incredible classic records, but using it to push those sounds forward is really what both Damon and I are all about. When we made Freedom, we were thinking about Tom Petty, someone who we respect and who inspires us, but that record doesn’t sound anything like his music.

Walk us through the songwriting process for a Delicate Steve song.

There’s no standard way, really. I try to keep inspired in the moment and follow that inspiration to the end. For instance, “Way Too Long” happened exactly as it’s laid out and unfolds on the record. I made that drum beat first, then came up with the chords, and then came up with the guitar part—the same way they enter the song.

The last song on the record, “Dream,” was a first-take pass of the chords. There’s a weird chord that accidentally slips from a major to a minor, but I left it in the song because it sounded really cool and I could never think of that—it just happened in the moment. The overall thing that’s present on every song is spontaneity, and that’s important to me. It’s all about getting out of your own head, whatever way that needs to happen, and you have to be okay with little mistakes when you’re trying to capture some magic in the moment.

Your music is very playful in a refreshing way. Instrumental guitar music can take itself very seriously.

On my first album, I had a revelation about playfulness or the idea that something is only serious when it’s in a minor key. Before that point, I was like this serious guy who wanted to make serious music that touches and changes the world. Everything was in a minor key and the heaviest sounding thing possible. Once I snapped out of that on my first album, it opened up the world to me and allowed me to have more fun and still take what I do seriously.

You play a lot of slide guitar in a unique style that sounds divorced from blues or country music. Where did that side of your playing develop?

The reason I picked up a slide in the first place was Duane Allman, and that was a big influence initially. Then Derek Trucks was the bridge for me to start thinking about how the slide guitar can mimic singers, because here was a guitarist I liked who sounded like a soul singer. His slide style shaped my own process in general and the idea that I too could be influenced by singers. Those are the two big influences that guided me to pick up a slide.

Guitars

1966 Gibson Melody Maker SG with PAF humbuckers

Gibson Joe Bonamassa Flying V

Amps

1968 Fender Deluxe Reverb (previously owned by Robbie Robertson) modified to use the reverb send as an extra gain stage.

Effects

Vintage Ibanez SD-9 Sonic Distortion

ZVEX Fuzz Factory

Vintage green box Big Muff

Earthbound Audio Supercollider fuzz

Valeton Coral Mod multi-effects

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Super Slinky (.009-.042)

Either a U.S. quarter or Herco Flex 75 Heavy held upside-down for scrape effect

I love the fuzz tones you get on the new album—especially on “Freedom” or that very compressed fuzz on “Way Too Long.” How did you cop those sounds in the studio?

It’s all pretty much the same chain, which consists of the first three pedals the studio owner, D. James Goodwin, pulled off a shelf that held a sea of incredible wacky, crazy, rare vintage fuzzes, overdrives, and distortions. One was an Ibanez SD-9 Sonic Distortion, which looks like a Tube Screamer from the ’80s, but is more of a distortion than an overdrive and sounds kind of thin. After the SD-9, I ran into a Big Muff, and then into a ZVEX Fuzz Factory. We split the signal into one of Robbie Robertson’s personal Fender Deluxe Reverbs that was at the studio [The Isokon] in Woodstock, New York. We close-miked the amp and also used a room mic. We pulled a DI signal off of the last pedal, as well.

The sound of the whole record is pretty much various combinations of those three drive pedals captured through those two mics and a DI, and I didn’t really do any post-production tweaking or EQ on it. I also used an MXR Analog Delay and this $50 pedal called a Valeton Coral Mod that has like 20 different effects in it. I used that for some envelope filters and modulation.

The guitar I played on the whole record was sold to me by my friend, a guitarist named Ofir Ganon, who is the only guitar snob-gear guy whose opinion I care about at all. Ofir sold me a ’66 Gibson Melody Maker SG, which had PAFs in it. The whole album is that guitar.

Everything was running through this really cool 1972 MCI board. I’d tweak some levels going in for each song, and once I got a blend for those levels—without touching settings on pedals or mics—I’d record the tune. Andrew Maury, who mixed the record, would then take my blend and put it down to one channel and mess with it there a bit, if he needed to.

You’ve done some recording with Paul Simon. What was that experience like?

I don’t know quite how to describe the experience to someone that might see it through the lens of “Oh! It’s Paul Simon!” I really just tried to see him as this guy that really had it together and was able to work on music at a level that’s higher than anybody I normally work with. That’s what I thrive on and want to have happen all the time. I want to get as deep into a song, or a part, or my own head, as I did with Paul Simon.

I was in the control room with him and my amp was in the other room. I knew he wanted slide guitar on the song, which he told me was in the key of D. He played me the track once and then muted the vocal and pushed record. I started playing along and then realized he was actually singing the vocal into my ear, maybe a foot away from me! He was pitch-perfect.

The take finished and I didn’t think I’d done anything worth keeping, but we basically used 80 percent of my first take on the track because Paul’s genius is getting the complete subconscious out of somebody, and then also having the precision to edit it right. There was a part of me that was sad because I wanted to really get into it and I felt I hadn’t given the song anything yet, but when I heard it back, I was really blown away.

Most often, what limits us is our own mind and how we interpret things, so if you can find a way to escape that or have someone who’s able to guide you or get that out of you—in this case, it was Paul Simon—cool things happen. What Paul coaxed out of me was cooler than anything I would have come up with after 20 takes.

Watch Steve Marion rip through a set of Delicate Steve tunes live in Los Angeles.

Amen Dunes onstage in Brooklyn with Steve Marion on lead guitar.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)