At an outdoor bluegrass jam in Indiana I saw a woman in her late eighties, a friend of my wife, playing an honest-to-God, prewar Martin D45. I asked her if I could play it, and I noticed that the side of the guitar had picked up a big chunk of grass and mud when she laid it down by her feet while eating fried chicken during a break in the music. George Gruhn might price this guitar around $150K today, which is about double the value of this woman’s house. She and her sister Esther bought new, matching Martins in the early forties, and they’ve been playing them ever since—these days mainly at their weekly nursing home gigs and bluegrassy, covered-dish get-togethers (to see this little old lady strumming the tar out of her Martin is a holy thing). Go to a bluegrass jam and you’ll find that this is not uncommon. It’s all old Martins and Gibsons. These salt-of-the-earth, working-class bluegrassers laid out serious, hard-earned cash for their instruments, buying the best they could afford. One might assume these instruments were relatively cheap at the time, but that’s not the case.

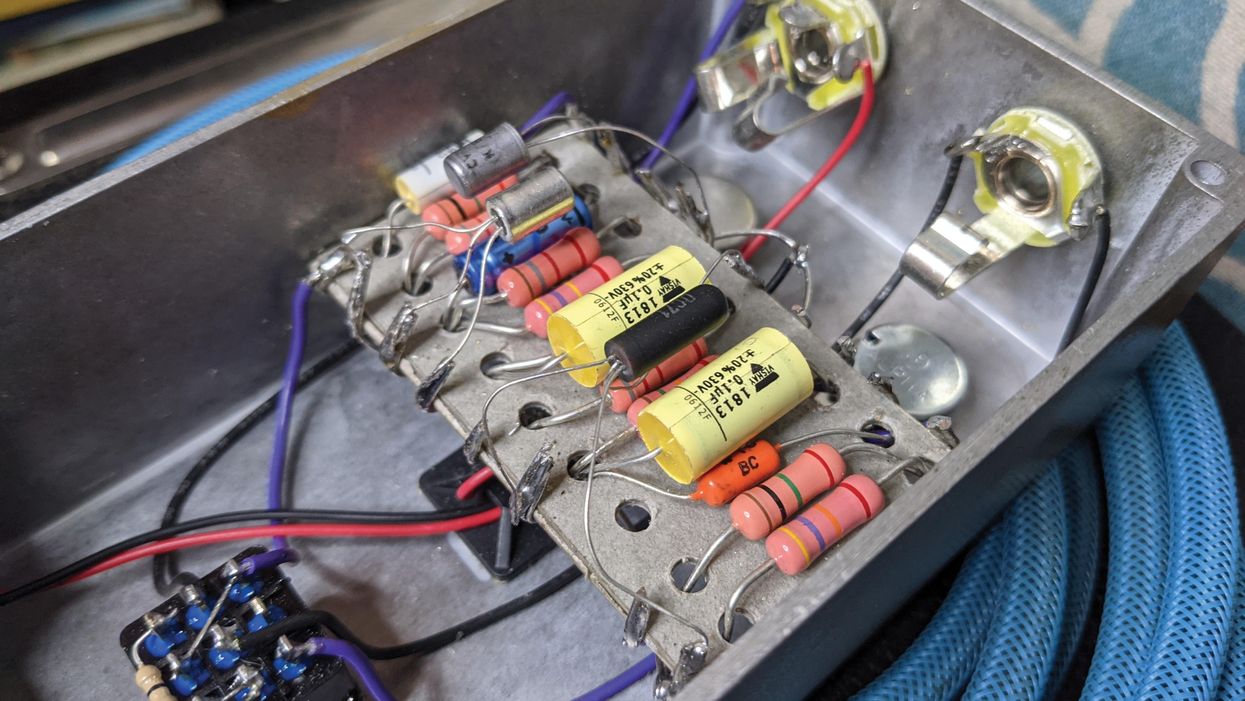

My friend Rick Gessner, a builder of brilliant tube amps, hipped me to a 1958 Gibson catalogue; it was a thought-provoking read. As I made my way through this catalogue, I began to yearn for a DeLorean with a flux capacitor. Here are a few mouth-watering examples: In 1958, Gibson’s 35W GA-70 amp cost $260, which translates to $1809 today. The Les Paul Standard gold top cost $247.50 (case $42); that’s $2054.33 today. The three-pickup Custom cost $375, which today would be $2661.04, or around 3K including case.

A comic/tragic side-note: Gibson’s triple neck non-pedal steel cost a whopping $895 in ‘58. Sadly, some poor steel-guitar geek who bought this instrument new could turn it for about a grand today, but he could have purchased two ‘58 LP standards and one custom for the same amount and cashed in for a cool million.

Much like today, money was tight in the ‘40s and ‘50s, but people wanted quality and they were willing to pay for it. Smart buyers ended up with instruments that appreciated, and wise companies turned a profit while building legendary brands. Asian companies manufactured guitars in the ‘50s and ‘60s, as well. Today, most of their old relics are worthless, while most of the work of their US peers has appreciated greatly—because the American companies strove to build the highest quality instruments with the finest materials, while others set a goal of high production at a low cost.

Gibson’s Epiphone plant in Asia has done well, making good guitars at affordable prices, but this foreign-shore outsourcing has unexpectedly bitten them in the ass. The foreign builders have gotten so good at making Les Pauls that they now produce nearly perfect knock-offs. My brother Mark owns a chain of pawnshops in Wyoming and Colorado, (City National Pawn—I’ve bought some great old gear out of there over the years). In his remote stores deep in the heartland, he’s seen a few Les Paul copies that I can’t tell from the originals. Luckily, he can, and he turns them away. Now there are thousands of authentic-looking, fake Gibsons flooding the market and falling apart on unsuspecting buyers who think they’ve found the deal of a lifetime.

My friend Winn Krozack, from PRS—a full-on genius who knows more about making guitars than anybody I know—purchased a cute, little, girly, import guitar for his adorable daughter. He test-drove the flowery thing and thought, Man, for an inexpensive guitar this is surprisingly good. And it was for a few months, until that cheap, green wood and shoddy parts disintegrated into unplayable crap.

American manufacturers’ salvation lies in creating timeless classics in a disposable world. Given the numbers in the 1958 Gibson catalogue, today’s boutique amps and serious guitars are (in a lot of cases) not much more expensive than those built in the USA when manufacturing was in its prime and we were the innovators. There are committed craftsman, like Valvetrain, Hahn, and Gadow, who toil in small shops to create new classics, much like Leo Fender and Orville Gibson did back in the day. In roughly 20 years, Paul Reed Smith and Bob Taylor went from two guys in their garages with a few hand tools making one great guitar at a time, to gigantic companies making thousands of great guitars at a time. Their success came from their commitment to creating timeless classics rather than quicker, cheaper, disposable shit.

American companies don’t need corporate welfare. Instead of competing in the race to the bottom—the race for the fastest, cheapest disposable crap—they need to love their product and watch their quality control. Then the whole world will cherish their instruments for centuries to come. This recession is no hype. Many companies struggle to make their numbers, and few of us can justify buying another guitar when we don’t know if we will be employed in a few months. I do have a few things on my wish list that I’ll buy when my income allows; they are made here and they will appreciate in time. More importantly, I’m going to enjoy the hell out of playing them.

John Bohlinger

John Bohlinger is a Nashville guitar slinger who has recorded and toured with over 30 major label artists. His songs and playing can be heard in several major motion pictures, major label releases and literally hundreds of television drops. For more info visit johnbohlinger.com.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)