I landed the gig as bandleader for this year's CMT Music Awards. Last year, I did a show with the producer, Tom Forrest, a brilliant, fun guy who's produced a ton of amazing music-based television, including the Crossroads series for CMT. Our show went well, and he was kind enough to hire me for this gig. In addition to the live performances, my gig also includes pre-recording music for the introduction packages, those rocking tracks beneath a voice-over saying something like: “The nominations for this year's best eighties rock- sounding song featuring a pedal steel and fiddle are..."

For the last two weeks, I've been chained to my home studio, elbow-deep in Pro Tools LE, armed with three electrics, a dobro, an acoustic, a mandolin, a bass, an E9 pedal steel, an X50 keyboard, a tube amp, a Shure KSM44 and a SM57 mic, an old drum machine, a few harmonicas and a handful of looping and sound-generating programs like EZ Drummer. I've had to build a considerable arsenal of sounds over the years, because I've stumbled into so many of these kinds of jobs, placing a couple hundred songs in television and film over the past seven years. What's the magic ingredient that makes songs work in television you ask? I am willing to give you, loyal reader, the keys to the kingdom. Four little words, my friends: Big Dumb Guitar Riffs.

Perhaps it's all part of the decline of Western civilization, but complicated melodies don't seem to work today. You can literally play your way out of a gig if you go too cerebral. Go online and listen to television themes from the past like, Family Feud, The Price is Right or Wheel of Fortune. They have real melodies you can sing, usually played by horns. Now compare today's competition, shows like Idol. Modern television music doesn't use songs, but riffs. Maybe our brains have atrophied to the point that we can't process anything complicated, or maybe the shift in music stems from the hypnotic effect of big dumb riffs. The listeners don't have to think to process the information. Instead, they absorb it unthinkingly into their central nervous system, which reacts by sending more oxygen to their muscles, pumping out some endorphins and generally getting the audience pumped to watch some mindless programming. The vast majority of modern television tracks strive to do one of two things: 1) make the audience feel tension; 2) make the audience feel excited and happy.

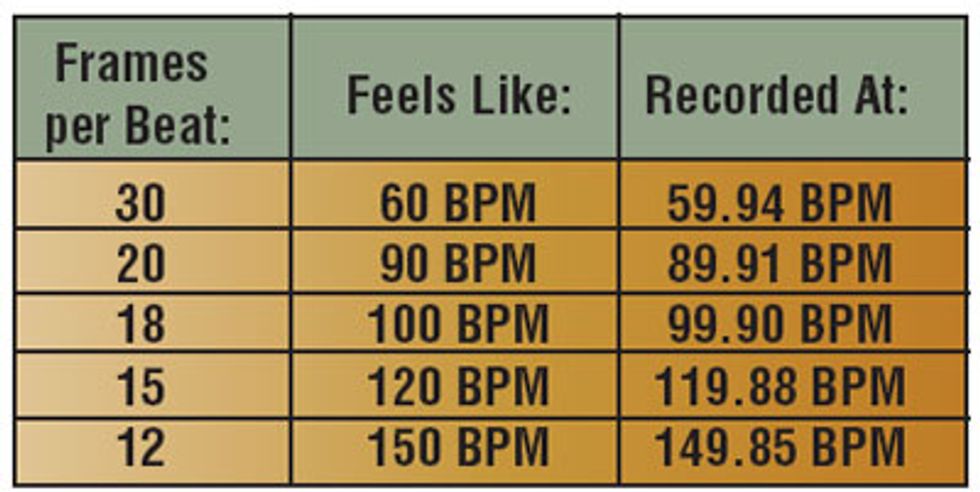

Partial list of “Magic Tempos" compiled by Chris Meyer, 1998. |

Tension is easy to create. Usually it's just a low, pulsating key patch with layers of tones sonically interlinked. I try to spice these up by adding some rocking riffs peppered about, and maybe a few seemingly arbitrary drum fills, like Clapton did on the old Lethal Weapon soundtrack. Sometimes playing open chords on a baritone guitar with tremolo makes for a track replete with dread and fear.

Excited and happy tracks require a bit more inspiration. The best are all balls, no brain. Acts like AC/DC, John Fogerty, or even The Ramones and Jet are masters of infectious, knuckle-draggin' riffs that hit everyone on a primitive level—no complicated rhythm patterns, never a string of 16th notes when a single quarter note will do.

One reason that simple, big riffs work so well in television is the way shots are cut. Watch the pace of any show and notice how the music changes as they switch cameras. In the best of all possible worlds, the shots change on the beat. A more obvious driving beat makes these cuts flow.

If you really want to get anal when prerecording for television, keep in mind that sound waves vibrate at a faster rate than frames happen in video or film. In layman's terms, our BPMs (beats per minute) do not line up with their FPBs (frames per beat). For example, say we want to record a rocking little ditty at 120 BPM. Our beats will land in front of the video frame changes; however, if we accommodate for this frame drop by recording at 119.88 BPM, the changes will line up perfectly. I was hipped to this by David Bennett from CMT Graphics. I could give you a somewhat complicated mathematical equation for calculating the frame drop-BPM conundrum, but we will all be better served if I just list a few common tempo examples that I found in an article entitled “Magic Tempos" by Chris Meyer (read the entire article at provideocoalition. com/index.php/cmg_keyframes/story/ magic_tempos/).

It's not as complicated as it seems. Pro Tools allows you to set tempos in smaller increments than you will ever need. Some looping programs have options that accommodate for frame drop.

Even though the last two paragraphs sounded like tech talk at a Star Trek convention, my point remains simple: catchy, easy, hypnotic riffs work best for film. It's not rocket surgery.

John Bohlinger is a Nashville guitar slinger who has recorded and toured with over 30 major label artists. His songs and playing can be heard in several major motion pictures, major label releases and literally hundreds of television drops. For more info visit johnbohlinger.com.