Photo courtesy of Shore Fire Media |

But while Di Meola was a terrifyingly dexterous electric guitarist, he was also a remarkable acoustic shredder, as he proved in the early 1980s trio he led with co-guitarists John McLaughlin and Paco de Luc’a—a group whose fiery sound was captured on the 1981 recording Friday Night in San Francisco.

With his string of 1980s solo albums— including 1980’s Splendido Hotel and 1982’s Electric Rendezvous—Di Meola continued to explore a synthesis of rock and jazz with Latin and non-Western idioms. His extreme playing earned him reverence from guitarists of all stripes—although some detractors also said his virtuosity unsuccessfully masked a lack of musical content and expressiveness.

Undeterred, Di Meola soldiered on in the early 1990s with a new group, World Sinfonia, whose main benchmark was the work of the Argentinean composer and bandone—n player Astor Piazzolla—inventor of the modern tango. His work during that decade, including on 1994’s Orange and Blue and 1998’s The Infinite Desire, focused less on blazing lines and more on composition, a trend that would continue into the 2000s.

For his latest offering, Pursuit of Radical Rhapsody, Di Meola worked with World Sinfonia to create a largely acoustic album of tunes that draw inspiration from tricky Latin rhythms and global sojourns. Largely absent are the guitarist’s over-the-top solo flights of decades past. Instead, the focus is on the ensemble, kaleidoscopic changes in instrumentation and texture, and rhythmic and harmonic invention. The result is a depth of musicality that should confound Di Meola’s earlier critics.

In the 1990s, you stepped away from the electric guitar for a while. Why?

For one thing, the appeal for the extreme volume that I started off with in the ’70s had waned over the years. I got sick of carrying around a ton of heavy equipment—it was such a physical and financial drain. Things had been so much easier with the acoustic trio I played in with John McLaughlin and Paco de Luc’a. So I was thinking about that group, and something else happened: I was developing as a writer and found that I could express myself better and make more meaningful music on the acoustic—and audiences really responded to that.

In what ways do you express yourself better on the acoustic?

My ideas don’t get lost in a wall of distortion and pyrotechnics, and I tend to write music that’s both subtler and more rhythmically adventurous on the acoustic. But in the last few years, I’ve been reintroducing the electric a little bit at a time, often mixed in with my acoustic sound by way of a processor like the Roland VG-88. After all, the electric sound is such a big part of my history, so I couldn’t just turn my back on it completely. It’s good to be back.

Having had that break from the electric, do you find that you now approach the instrument differently?

To answer that, I have to look back to my early days playing fusion in the ’70s. My electric solos were so often based on the static harmony—a single chord, like E minor or A minor, for a long period of time—that was so popular then. There wasn’t much I could do on that one chord except build up to the sort of highly technical, velocity-laden type of climax that audiences ate up. It was certainly exciting at the time, but I’ve come to appreciate a lot more harmonic movement in music, as well as strong balance—a good combination of space and lyricism, with speed and technique thrown in there at the appropriate moments. How I play the electric guitar has as much to do with my focusing on the acoustic guitar—where every little nuance is important—as it does simply evolving as a musician. I can now say more with an interesting progression or a syncopated rhythm than with a barrage of notes at high volume.

The electric playing on Pursuit of Radical Rhapsody is characterized by restraint and gracefulness, as well as by awesome tone. How did you get such great sounds?

I played my PRS—the signature model Prism, which is a double-cutaway solidbody with two humbuckers and a very warm sound. But the secret weapon was a Dumble amp I borrowed in the studio. I discovered that the beauty of a Dumble is in the smoothness of its sustain, and I could see right away why they’re so coveted and expensive. Most other amps might sound smooth in the booth when you’re recording, but on the other side of the glass, in the control room, you’ll hear all these jagged edges on the sustain. That Dumble was like cream, like butter—a small amp with such a great sound.

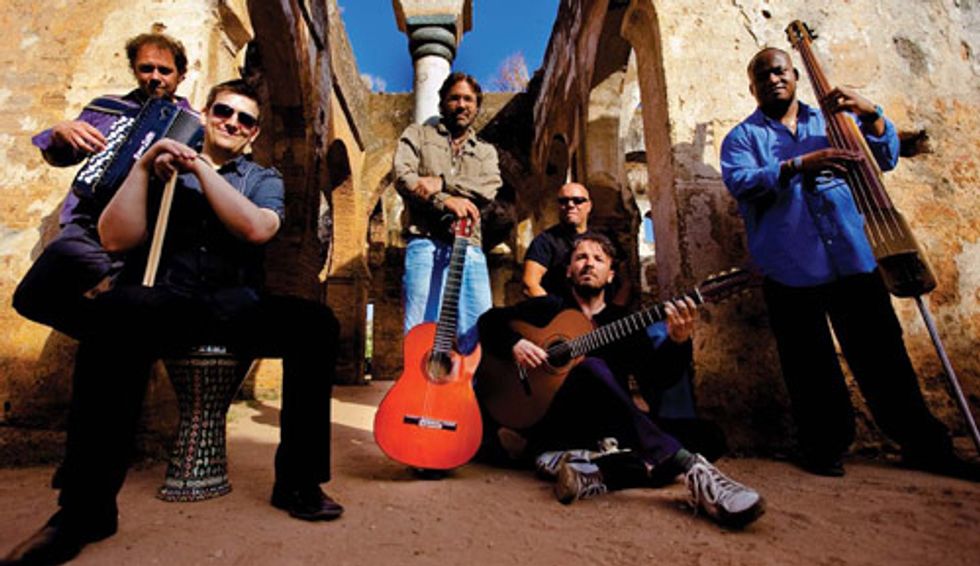

Di Meola (center) and World Sinfonia—(left to right) Faust Beccalossi, Peter Kaszas,

Peo Alfonso, Gumbi Ortiz, and Victor Miranda. Photo courtesy of Shore Fire Media

Is there any Roland VG-88 on the record?

Yes. I used a little bit of that on acoustic parts here and there, as well as a GR-1 guitar synthesizer, which has been discontinued but is, in my opinion, the best one Roland has made. On “Destination Gonzalo,” for instance, I played my signature model Ovation and combined the basic acoustic-electric sound with a fretless bass setting on the GR-1 to get this really awesome effect.

Although the guitar really does shine, the album seems to be more about the ensemble than your own playing.

I paid extremely close attention to how all the instruments blended together. In the past, I’ve used the combination of acoustic guitar and piano or synth, but I’ve come to find that keyboards can be a little overbearing when played with a nylon-string. The instruments’ timbres can be too close together, because both have strings. There’s a lot of accordion on the record, courtesy of the great Fausto Beccalossi, and that instrument works really well with the guitar— especially when adding counterpoint. With their completely different sounds, accordion and guitar are so beautiful together, very European and romantic. And the accordion adds a depth and meaning to the sound that you just can’t get from an electronic keyboard.

In addition to your usual World Sinfonia co-conspirators, you had some pretty distinguished guests on the record—jazz bass legend Charlie Haden, Cuban pianist Gonzalo Rubalcaba, and others.

Right—it was great! Charlie’s a super-legendary and super-friendly guy. He was amazingly easy to work with, and he brought an unusual gut-string upright bass for the session, which had a really beautiful sound—especially for ballads. It worked really well on “Over the Rainbow,” which has this nostalgic feel. Working with Gonzalo was also great. What can I say—he’s a super god on the piano! It was such an honor to have him, Charlie, and also [jazz drummer] Peter Erskine on the record. They were all so supportive and happy to be part of the session. Their enthusiasm was infectious and brought out the best in all of us.

You also worked with a second guitarist, Kevin Seddiki. Did you find this freeing?

Yes, it allowed me to take on both soloing and accompaniment roles, both on the album and in concert. But more important, I really like the sound of two guitars at once—it’s sort of the nucleus of many of my pieces, and it’s what I first hear in my head when I’m composing. Working with two guitars can be a little tricky, though, because to the listener they can be indistinguishable from one another. This is easy enough to address in the studio, just by panning one instrument right and the other left, but I’ve also found that it helps keep the sounds separate to use a nylon-string and a steel-string, which have such nicely contrasting sounds.

Speaking of composing, what was your writing process like for this album?

It wasn’t so unusual. I sat down in my home on the beach in Miami and wrote all the parts. I’d normally start with the arpeggios that form the structure of a piece, followed by the melody and a bass line, all with lots of counterpoint. That’s the beginning skeleton of any written piece of mine. From there, you can do anything.

Did you actually write out the parts, or did you record them and play them for the other musicians to learn by ear?

I did things the old-fashioned way: I wrote out all of the individual melodic and harmonic parts—everything but the percussion— painstakingly by hand. Then I took the charts to rehearsal and had my drummer, Peter Kaszas, and percussionist, Gumbi Ortiz, work everything out. My only compositional input and my general rule of thumb is that a percussionist and drummer shouldn’t play the same things. Each should have independent parts that create a massively syncopated whole.

There are lots of international sounds on the album—and in your music in general. Can you pinpoint specific influences for that?

I feel so at home in the world of music. I was born in the United States but don’t sound at all like an American. My music is influenced by different Latin styles and rhythmic derivations. This goes back to when I was a teenager and would hang out in Latin clubs in New York City and soak in all the complex rhythms. About 25 years ago, I totally immersed myself in the world of tango and in the works of Astor Piazzolla—which sit really well on the guitar but have been played by very few guitarists. I took the music—which is not just intellectual and technical but so deep and heartfelt—and made it my own by adding extreme syncopation and all kinds of unexpected rhythms. This influence also worked into my own compositions—not in terms of any one element, but more the overall passionate sound of the music.

But I’m into so many other styles—a lot of classical, Middle Eastern music, and so on. And I tend to soak in sounds where I travel, not by reading transcriptions or books about the music but more in a subliminal way. It just takes over and ends up in my music. For example, not long ago I visited Morocco with the group, and you can hear that influence on the new two-part composition “Mawazine.”

Di Meola onstage with his Conde Hermano classical guitar. Photo by PhotoMafia

Talk a little about recording Pursuit of Radical Rhapsody, which sounds so naturally flowing. Was it done live?

Before we even went in the studio, the ensemble spent almost a year rehearsing the tunes on the road. Everyone developed a comfort level with the compositions and began to take more liberties with their own embellishments, which lent character to everything, along with a good feel and groove. In other words, the rehearsals were kind of part of the writing process. Another good thing is that rehearsing the songs so thoroughly for so long afforded me the chance to take away ideas or add them to a piece—to remove an unnecessary part that was weighing things down or to add a cool chord change. So by the time we got to the studio, everybody was very comfortable with the material and we were able to record the album mostly live.

We used overdubbing sparingly for the occasional extra drum part or guitar solo. That’s pretty much the opposite of the way things are normally done these days. Musicians go into the studio after a quick rehearsal to record, which means their compositions haven’t gotten the chance to live, breathe, and develop. Most people actually don’t even record with bands anymore— they just layer tracks one instrument at a time, and it definitely shows.

The record is filled with uncommonly complex chord progressions. Do you have any pointers for someone who’s just learning to play over changes?

First, arm yourself with a knowledge of theory, which will help you identify which scales apply to a given chord. Then make sure you’ve got those scales under your fingers. When you’re faced with a new progression, a good basic rule to make it all work is this: Use the appropriate scales and play things very slowly while you think about the smoothest way to get from one chord to the next. For example, one new track, “Siberiana,” has a bunch of chord changes. One of the sections starts off on an F#m chord and then moves to Am. So if you’re playing a C# over the F#m chord, you can move down a half-step to C to land smoothly on the Am and make the change.

You can also look for a common tone— one note that can be played over different chords. The note E will work on both an F#m and Am chords. That way you can focus on doing a lot of really cool things with rhythm and syncopation. That’s something that’s never really talked about—the importance of rhythmic improvisation.

What would you recommend to a player who’s struggling with rhythm?

You first have to connect physically to whatever it is you’re practicing. If you’re having problems, it’s best to start with something simple in 4/4. Before you even play a note or strum a chord, tap your foot in quarter-notes, making sure that the foot is very steady. Then, try adding the guitar playing, making absolutely sure the foot maintains a consistent beat. If the foot is doing what it should be, then you’ll be able to add the upper rhythms—the ones you play against the beat on the guitar. But if your foot sways even a hair, it’s all over. At that point, you’re going to have to take things down to a ridiculously slow tempo and tap along with a metronome until your foot gets its act together, because if it’s not doing what it should then you won’t be able to hold things together, rhythmically. In the end, rhythm is the most important thing—and it all comes from the foot.

Al Di Meola’s Gearbox

Guitars

Ovation Al Di Meola signature model, 1948 Martin D-18, Conde Hermanos nylon-string, PRS Al Di Meola Prism, Gibson Al Di Meola Les Paul, Gibson Al Di Meola hollowbody

Effects

Roland VG-88 Guitar System, Roland GR-1 Guitar Synthesizer

Amps

1979 50-watt Dumble Overdrive Special driving a Mesa/Boogie 2x12 cab with Celestion Vintage 30 speakers

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXL110 electric sets, D’Addario EJ16 steel-string acoustic sets, Savarez nylon-string acoustic sets, extraheavy D’Andrea picks

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)