The kindest Deadheads are empathetic to those who don’t immediately grasp the Grateful Dead’s art and appeal. The band’s music, after all, was loose, searching, inventive, improvisational, and, on occasion, utterly lacking form as most Western music audiences would understand it. That’s partly because, unlike some contemporaries that were uniformly inspired by the British invasion and folk rock, the Grateful Dead arose from a much more divergent set of influences. But no member of the ramshackle Haight-Ashbury dance combo was an odder fit than bassist Phil Lesh, who passed away October 25, 2024 at age 84.

Where guitarists Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir, organist Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, and drummer Bill Kreutzmann’s influences overlapped to various degrees via bluegrass, folk, blues, and soul, Lesh was reared as a classical musician and gravitated to minimalism, modern composition, and avant jazz before falling under the spell of the Warlocks (as the Dead were then known) and their raw fusion of Stones-style garage blues and twisted folk. Lesh’s almost paradoxical distance from a typical mid-’60s set of influences, and visceral response to the immediacy of those musical forms, made him a vital bonding agent that held the Dead’s disparate musical threads together. And in another very-Grateful Dead bit of yin-yang duality, the unconventional approach to electric bass he developed from a jazz and classical vocabulary were a platform from which the Dead could elevate their rootsiest leanings to stratospheric heights. In the documentary Long Strange Trip, discussing survival strategies the Grateful Dead used to perform while chemically altered at Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests in 1965 and 1966, Lesh said simply, “You have to listen.” Both his ear and irreverent disregard for convention served the Dead well as they evolved from the Kings of Golden Gate Park into a mass cultural phenomenon.

Lesh was born on March 15, 1940 in Berkeley, California—fortuitously, in a time and place that positioned him for a future as avant-garde composer or psychedelic rock pioneer. Between this twist of geographical good fortune and his copious talent, it was not improbable he would become both. Lesh’s exposure to classical radio as a child sparked early enthusiasm for Brahms and Bach, which led him to violin and a spot in the Berkeley Young People’s Symphony. At Berkeley High School, he switched to trumpet and began to ingest the leading-edge jazz erupting from America’s bohemian centers in the late ’50s and early ’60s.

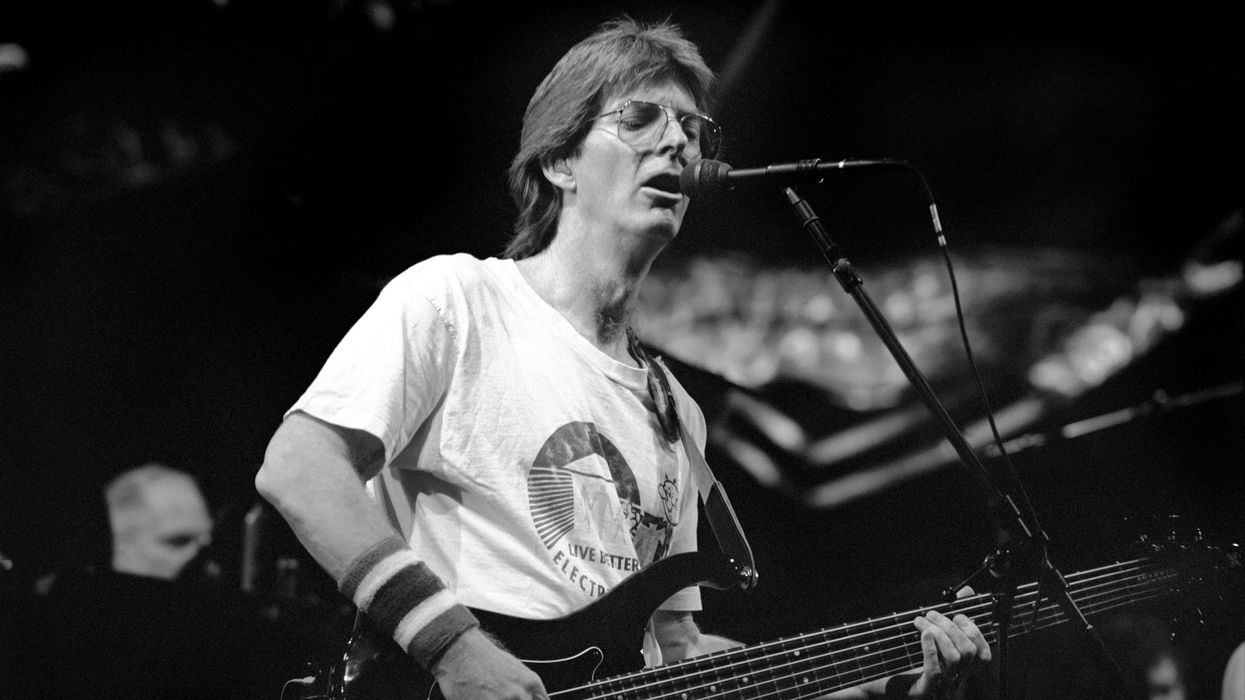

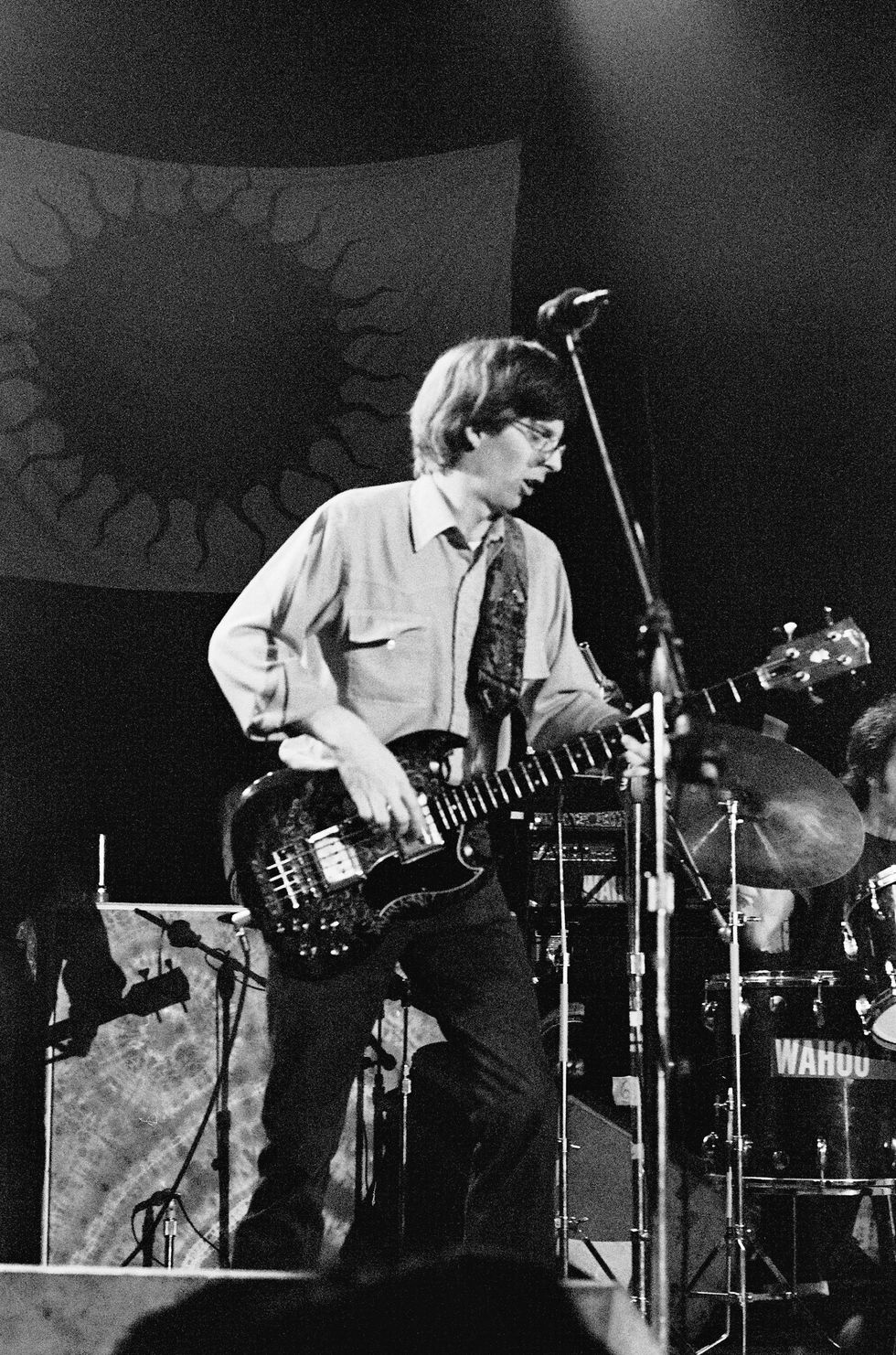

In 1971, a fresh-faced Lesh plays with the Dead at the Manhattan Center, using his red paisley Gibson EB-3. That year, the band released its live Grateful Dead album.

Photo by Peter Corrigan/Frank White Agency

For anyone fascinated by modern music at that time, the Bay Area was an Eden. In addition to being a focal point for newer, freer strains of jazz (and extended residencies that sustained those scenes), it also witnessed the birth of the San Francisco Tape Music Center, a ground zero for experimental electronic music that brought together synthesizer pioneer Don Buchla and modern composition giants Morton Subotnick, Pauline Oliveros, Terry Reilly, and Steve Reich—the latter of whom became a classmate with Lesh when he moved from the University of California, Berkeley, to Mills College in Oakland.

Lesh might have been drawn deeper into avant circles, were it not for the fact that the Bay Area was also a hotbed of bellicose and melodic teenage guitar rock and soul—and in its more southern bohemian enclaves around Stanford University and San Jose, a fast-mutating graft of folky older American traditions, blues, Rolling Stones, Beatles, Animals, Kinks, Byrds, and the Beats that was bearing strange fruit. Lesh wandered into this milieu, already home to Garcia, Weir, McKernan, and Kruetzman as the Warlocks, some time in 1965, after Garcia invited him to see the Warlocks in Menlo Park. Lesh was, by his own account, knocked out by the band’s scrappy potency and rawness and was asked by the ever-intuitive Garcia to join the band on bass in spite of (or precisely because of) Lesh’s relative unfamiliarity with rock idioms and his experimental leanings.

By the time the group became the Grateful Dead later the same year, it was evolving into a crack dance band well-suited for Bill Graham’s and Chet Helms’ ballroom scenes. Critically, the Dead proved equally well suited for another set of social experiments unfolding around the Bay’s hill and beach towns with the help of author and Merry Prankster Ken Kesey: the Acid Tests.

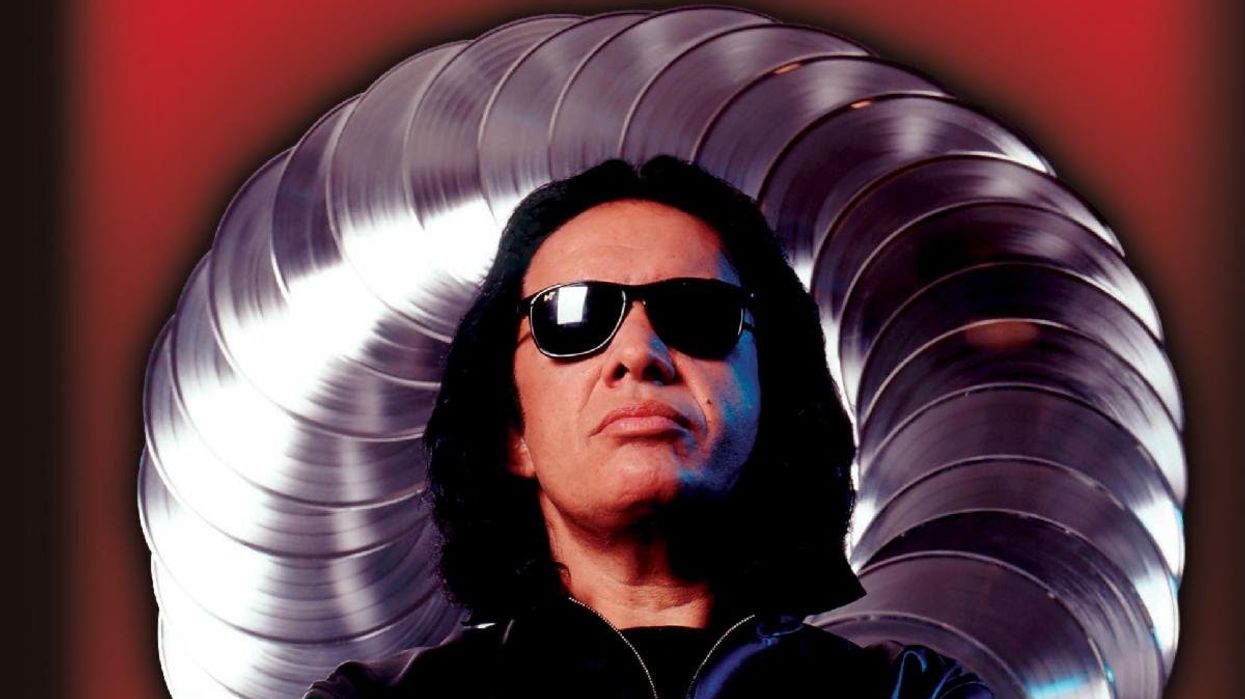

Phil Lesh holds down the bottom on a Modulus Graphite 6-string bass at Giants Stadium in June 1995. By the end of the summer, Jerry Garcia would be dead and the Grateful Dead would begin morphing into various spin offs.

Photo by Frank White/Frank White Agency

Though many fellow Bay Area bands explored psychedelic realms and evolved into more sophisticated players and songwriters at this time, few were touched by the magic convergence of artistic commitment and a lack of commercial ambition quite like the Dead. That made them perfect entertainment for the communal LSD experiences that were the Acid Tests. They could noodle around aimlessly for five minutes or play for five hours straight—chances were it would be all good for the dozens or hundreds of participants zooming deep into the night. That environment was also a perfect playground for Lesh to indulge his sense of musical discipline, lust for improvisational freedom, and his contempt for form and authority in equal measure. Such were the libertine latitudes afforded by the Acid Tests.

As the Dead jammed, played, and toured relentlessly through 1966, ’67, and ’68—for a time living together at 710 Ashbury Street—they cultivated a musical and band identity apart from their Fillmore and Avalon Ballroom contemporaries. They lacked the commercial potential of the Jefferson Airplane and Moby Grape (who nevertheless sabotaged that potential in their own special ways). They didn’t have Janis Joplin or Grace Slick star power, and their jams were hit and miss compared to the sometimes more fluid and lyrical extended arrangements of Quicksilver Messenger Service. But freedom from those constraints put them in their element, and Lesh in particular thrived there. Because he was less encumbered by rock ’n’ roll cliché, his technical and intuitive knowledge of the bass guitar fretboard and voice led to a melodic style that kept the Dead rooted and star-roving while putting him in league with Paul McCartney, the Byrds’ Chris Hillman, John Entwistle, Jack Bruce, and the Airplane’s Jack Cassidy.

But few of those players took that melodic sense as far afield as Lesh. And as long versions of “Viola Lee Blues” and “Morning Dew” stretched out and begat more complex extended pieces like “That’s It for the Other One” and the visionary “Dark Star,” Lesh stayed relentlessly engaged—providing melodic counterpoint to Garcia’s skyward-bound vines of filigree while maintaining intricate, swinging dialogue with Kreutzmann’s funky wanderlust.

“Lesh’s musicianship and drive helped the Dead forge their legendary status as a powerhouse improvisational unit and grew the band’s cult, which came to include a dedicated subsect, the Phil Zone.”

Listening to this conversation evolve via live recordings from the mid-’60s to the early ’70s can be exhilarating. Extra-long versions of “Dark Star” and “Playing in the Band,” from the Dead’s 1972 shows in particular, highlight Lesh’s unique chemistry with the band and his contribution of muscular propulsion, funky undercurrents, free-jazz energy, and impressionist elasticity. Lesh was also masterful in the studio, acting first as creative enabler, instigator, and agent of chaos on 1968’s Anthem of the Sun and 1969’s Aoxamoxoa—non-commercial, far-out, and experimental records that nonetheless primed FM radio audiences and curious record buyers for the Dead’s live voyages—and then as musical interlocutor when Garcia’s songwriting blossomed on Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty. Lesh started to contribute tunes, too. His masterful “Box of Rain,” a tender and melancholy folk-rock gem penned for his dying father, leads off American Beauty, the 1970 LP that defines the band for most casual listeners.

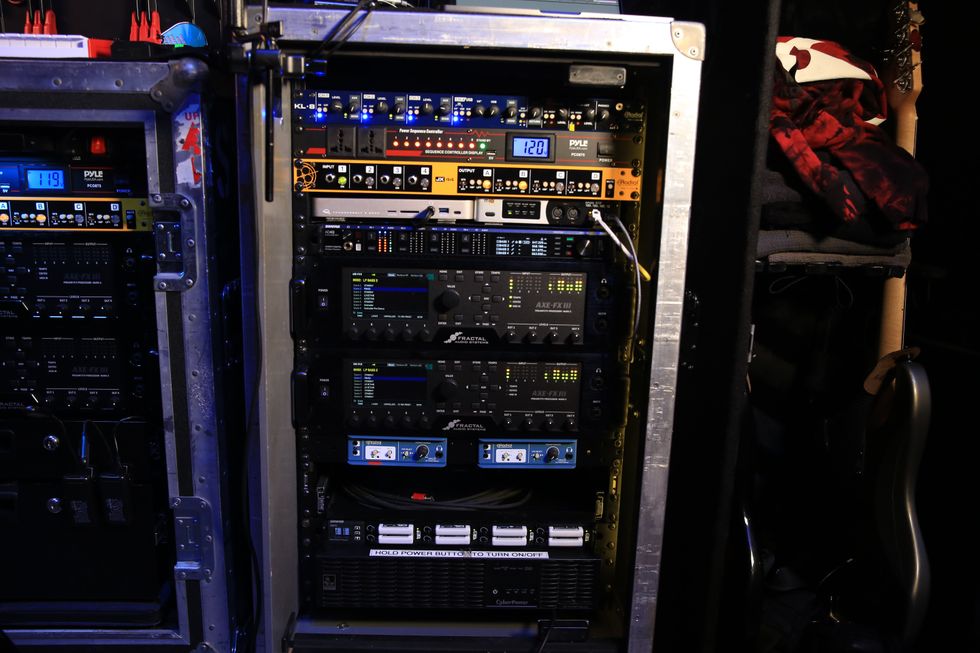

As the Grateful Dead evolved, ebbed, flowed, rested and returned between the mid-’70s and their unlikely commercial apex in the late-’80s and early ’90s, Lesh’s musicianship and drive helped the Dead forge their legendary status as a powerhouse improvisational unit and grew the band’s cult, which came to include a dedicated subsect, the Phil Zone—a section of showgoers that gathered stage right to swim in the bass frequencies from Lesh’s instrument. Lesh was among the band members that most savored the possibilities of the Wall Of Sound, a 604-speaker, high-power colossus of a sound system designed to envelop band and ever bigger crowds alike in an ultra-detailed tone picture which nearly broke the Dead’s crew before it was retired. He also explored enhancements of audio and instruments in collaborations with luthier and Alembic founder Rick Turner, yielding a much-modified version of Lesh’s Guild Starfire IV, known as Big Brown, and the more ambitious Mission Control bass, which was designed to function within the Wall of Sound—sending output from individual strings to dedicated speaker columns via an array of 11 knobs and 10 push buttons.

Lesh’s deep thought about music technology, ambitious approach to performance, and classical training sometimes lent themselves to perception as the Dead’s resident nerd and technician. Such perceptions, however, tend to discredit Lesh’s intense sensitivity to melody, feeling, soul, and song. David Crosby marveled at the way Lesh’s bass illuminated the intensely personal, pained, fragile, and beautiful songs on his solo masterpiece If Only I Could Remember My Name. And no less than Bob Dylan called Lesh “one of the most skilled bassists you’ll ever hear in subtlety and invention.” He was also a stubborn, laughing personification of how a passion for music breeds longevity, playing with a rotating cast of colleagues right up to a few months before his passing. Certainly, few rock bassists so deftly, freely, or joyously moved between fearless improvisation and selfless, sensitive support of so many great American tunes