Deafheaven is one of those bands that defies categorization. Part shoegaze, part black metal, part sonic annihilation, their music is a mix of ear-bleeding chaos, balls-to-the-wall riffage, poignant sensitivity, and quiet. A strange cross between Slayer, My Bloody Valentine, and the Smiths, Deafheaven makes these disparate influences sound obvious and natural.

The mad scientist, founding guitarist, and principle songwriter behind Deafheaven is Kerry McCoy. Hailing from Modesto, California, McCoy started playing guitar when he was 11. “My dad got a guitar when I was in fifth grade,” he says. “He had a really shitty beginner guitar, and then he got a new one and gave me his old one.” McCoy upgraded to a Squier Strat in seventh grade, and as he got older he got more serious about music, playing in bands and eventually discovering one of his formative influences, the Dead Kennedys. “I literally was such a nerd about it that I saved up my lunch money for two months to buy seven Dead Kennedys shirts—so I could wear one every single day of the week.”

According to McCoy, the Gilman scene—the Berkeley, California, punk movement that spawned bands like Green Day, Operation Ivy, and Rancid—spilled over into Modesto in the early 2000s, when he was a teenager. “Modesto is close to the Bay Area,” he explains, “and because of that there were a lot of people from the East Bay or South Bay that wound up moving to Modesto. That whole AFI-, Nerve Agents-type of punk and hardcore that I came up in was there. Early on, that whole scene influenced my sense of melody and songwriting.”

Given Deafheaven’s mélange of styles, it goes without saying that McCoy was into other music as well, including heavy metal. That’s what led to his friendship with George Clarke, Deafheaven’s future lead singer. “I complimented George on his Slayer shirt,” McCoy says. “That’s actually what helped us become friends.”

After a few fits and starts, the pair launched Deafheaven in 2010. They released their first album, Roads to Judah, in 2011, but hit the big time in 2013 with the release of Sunbather. The album was a critical triumph and an endless topic of conversation: Fans, critics, trolls, and others argued the virtues—or lack thereof—of Deafheaven’s incorrigible mash-up of incongruous genres and styles. But easy to categorize or not, the band toured, grew their fan base, and became a force to be reckoned with. They also settled into their current lineup of McCoy and Clarke plus guitarist Shiv Mehra, bassist Stephen Clark, and drummer Daniel Tracy. Their new album, New Bermuda, finds the band growing, healthy, and working together. “This record was possible because there were four other heads in the room helping,” McCoy says.

PG sat down with McCoy to talk about pedals, crafting killer tones, his idiosyncratic songwriting style, and how pop-rock outfit Goo Goo Dolls has been—at the very least—subliminally influential.

How did you get into metal?

I was 14, and right before I met George, my friend who was the drummer in the band I played in gave me a CD of Slayer’s Reign in Blood. I never had an older brother or anybody to show me metal. All the metal I knew about was bands like Slipknot and Korn. I hated all that stuff and I hated the kids at school that wore their shirts. But then my friend burned me that Slayer CD and I thought, “Whoa, this is killer. This is not stupid sounding. This is sick and tight—and it’s dark.”

When you started playing guitar, did you get into pedals and effects right away?

Not seriously until this band. I never really had anything. I was in a couple post-rock bands when I was in high school—nothing that ever did anything—and I was really broke for a long time. The bands that I played in before this were grind-type gnarly stuff. When George and I started this band, we wrote the songs on an acoustic guitar and then borrowed equipment at the studio to put our demo together. Nick [Bassett] from [Bay Area shoegaze outfit] Whirr was in our band in the early stages, and he showed me a few things. But that’s why A) I am not a huge gear guy and B) I am not a big pedal guy. I manage to know enough about them now to not be an idiot, but I’ve always put a bigger emphasis on songwriting than on gear.

That’s interesting, because pedals are such an integral part of your sound.

Well yeah, they totally are—though 90 percent of that is delay and reverb. When it’s not, it’s essentially chorus, phaser, or a wah. It’s not anything breaking the bank.

When you compose with effects, they often cause you to play differently. But you usually compose on acoustic, then add effects later.

Early on that is what I did most of the time. It is so much more important to have a song that, when you play it on acoustic, still holds its merit as opposed to if you take away the effects, it is not really doing anything. If you have a song that’s good, it’ll be good on anything. If you have a song that is completely dependent on a certain delay bouncing a certain way, to me that’s kind of a crutch.

At the same time though, I am not an idiot when it comes to effects. I know how to do the Kevin Shields reverse-reverb thing on the blue Electro-Harmonix Memory Man and that is totally an effect that—when I use it—completely changes the sound of the guitar. But for the most part, effects are just there to enhance what’s already written.

You have a DigiTech JamMan on your pedalboard—do you do live looping during your shows?

No, I don’t. I got the idea from Mike [Sullivan] from Russian Circles. Mike has a bunch of really subtle sounds—just ambient noises—already on his JamMan that he runs everything through. While the guitar is fading out, he hits that JamMan and plays a sample of his guitar making some crazy noise or a synth doing something weird. It seamlessly flows in and out. I do the diet, little-kid version of that: I’ve programmed the interludes that were on our last record—19 or so little loops of various piano or noises or guitar or synth or spoken-word stuff or whatever—into the JamMan, and I run that through the PA. When the band is fading out I hit that and it gives us something to play while we’re tuning up, drinking beer, wiping ourselves off, and preparing for the next 12-minute thing.

Your songs don’t follow the typical verse-chorus-verse formula—they are much more symphonic.

A lot of that—even when I break that rule—comes from when I was younger and we were starting the band. I was trying to write stuff and not repeat riffs—and if I did repeat a riff, I would repeat it and then take it in a different direction. I was taking elements from each genre that I liked and applying them to my own whim. I would like this part from black metal, but I didn’t like it enough to repeat it 24 times—like, five minutes of this droning riff going on and on. We are the ADD black metal band. We play a riff four times and then throw it away. I like the buildups and a lot of the drama in post rock. I like how it takes you through these movements.

My big focus is on two things: hooks and transitions. A hook is not like your typical pop hook. A hook is anything that is syncopated, memorable, rhythmic, melodic—whatever your definition of melodic is—a part that you’ve written that you can’t get out of your head because it is so cool sounding. That is my emphasis. I want each part to be memorable. You know when it’s right, you know when a part is good: You get that feeling where it hits you in the gut and you’re, like, “Whoa. Where did that come from?” I told myself I would never let any riff pass by that didn’t do that to me. By doing that I made myself my hardest critic and inadvertently turned myself into a bit of a mess—a bit of a neurotic asshole who it’s hard to be in the band with sometimes. But in doing that I’ve tried to keep the quality of the riffs as high as possible. The other thing is transitions. For example, if you’re going to change keys, find a way to get to that next key. For me, a lot of times it’s days and days of grasping in the dark for that one note.

My songwriting pretty much comes from that: Not wanting to bore anybody. Wanting each riff to be as memorable and cool as the last—or even better. Wanting to make sure that each transition, regardless of what part or genre we’re going into, is going to be seamless. I think the result of that—at least what me and George get from it—is that a lot of the times we’ll write these songs, we’ll listen to them when they’re done, and we’ll get to the end of the song and be like, “God, I forget how it started. It is almost in a completely different place.” That’s a cool thing to me.

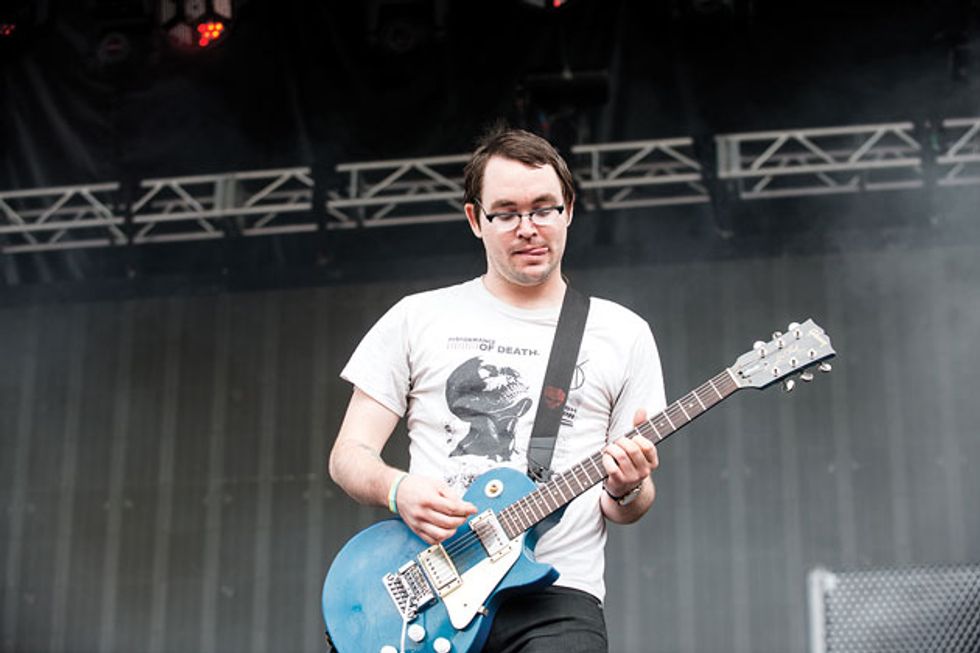

“It’s some weird fluke from the early ’80s when everybody was starting to buy Jacksons. I guess Gibson wanted to try to compete with the dive-bomb market,” says Deafheaven’s Kerry McCoy of his old Les Paul. The guitar is completely stock except for the removal of its locking nut. Photo by Lindsey Best

Do you keep a library of riffs that you can go back to and cull from?

I did at one point. That was before Sunbather, but that album pretty much exhausted all of those. That was part of what was so stressful about New Bermuda. We had been on tour for a year and a half—which was how long it took to write Sunbather—and then we got back and had four months to write the follow up. I hadn’t had time to sit down and fill that bucket back up with riffs. There were little somethings—ideas we had worked on on the road—but it is very hard to do that when you’re on the road. I was scraping the very bottom of that riff bucket I have in my brain, so a lot of New Bermuda was jamming in a very stressful environment and coming up with stuff. The problem with doing that is that you instantly question yourself, “Is this actually good or am I just stressed and wanting to finish writing the song?” But I am definitely happy with the final product.

Let’s talk a little more about transitions. The new album has a lot of contrasts: You’ll follow something bombastic and massive with something really beautiful. Jimmy Page has been quoted as saying he put the mellower songs on the Zeppelin albums because they made the heavy songs sound even heavier. Is that your thinking too?

I agree with that wholeheartedly. Some of the heaviest riffs in the world were written by Metallica in standard tuning. Deep tuning does not make you heavy. What makes you heavy are dynamics and tone and syncopation. A lot of these guys start at drop B, throw a Boss HM-2 [Heavy Metal distortion] on there, and then their big thing is slowing down the tempo, and then slowing down the tempo some more, and then a big drop out—and then another slowdown. If you start at 10, you have nowhere to go from there. If you have nowhere to go, 10 eventually becomes one. To me, the stuff on the new record that is heavy wouldn’t be heavy if it wasn’t followed up or preceded by some 4AD[-style] spacey slowcore stuff. [Ed. note: U.K. label 4AD is the home of indie bands such as the National, Bon Iver, and Deerhunter.]

Kerry McCoy’s Gear

Guitars

Dunable Moonflower

1980s Gibson Les Paul

Amps

Peavey 6505 head (live)

Top Hat Emplexador (studio)

Orange Rockerverb 100 (studio)

Emperor 4x12 cab

Effects

Ernie Ball volume pedal

Electro-Harmonix Stereo Memory Man with Hazarai

EarthQuaker Devices Rainbow Machine

EarthQuaker Grand Orbiter

Dunlop Cry Baby wah

Electro-Harmonix Holy Grail Reverb

Boss RE-20 Space Echo

DigiTech JamMan

Strings, Picks & Accessories

D’Addario NYXL regular light strings (.010-.046)

Moderate to heavy picks

Boss TU-2 tuner

You have a few solos on the album, but not many.

Absolutely not. We tried to emphasize that side of ourselves as much as was tasteful. It’s so fun to do that stuff—I would never claim to be Kirk Hammett or anything—but sometimes you’ve just got to let your inner wah-wah out.

Do you feel the guitar’s role is more atmospheric—to create colors and textures?

On past releases it was definitely more atmospheric, more for that airy quality. But on this record I tried to ground it as much as possible—I tried to make it much more of a riff machine and way less of an ethereal, ton-of-reverb, ton-of-delay thing. I put chugging and power chords in there to get back to your classic Hetfield-style stuff—but my take on that, obviously.

The beginning of “Luna” is a good example of that.

Exactly.

How did you create those tones—is that your 6505?

No. We didn’t use Peaveys on this record, that’s what I use live. Each guitar track is tracked twice, so it is four guitars total. Me and Shiv alternated between a 50-watt Top Hat Emplexador—which is essentially just a modded JCM800 with a little bit more nuts on it—and then an Orange Rockerverb 100, I believe. It’s [producer] Jack Shirley’s other amp. I can’t remember exactly. Shiv and I are each playing a rhythm guitar [track] and a lead. And we’re alternating both of our parts on both of those amps.

No. I do really like the Goo Goo Dolls, though. They were a big influence on Sunbather. When we were writing that I was listening to Dizzy Up the Girl a bunch!

YouTube It

Deafheaven treats a huge festival crowd to a kaleidoscopic blend of crushing riffage, atmospheric post-rock melody, bouncing ska beats, black metal screaming, and more. At 2:57, Kerry McCoy starts coaxing anthemic lines from his Dunable Moonflower.

Deafheaven frontman George Clarke snarls into his mic as band cofounder McCoy barres his custom, Kahler-equipped Dunable Moonflower.

The Dunables of Deafheaven

Kerry McCoy’s main guitar at present is a custom Dunable Moonflower built by Sacha Dunable—who also plays guitar in L.A. prog-metal outfit Intronaut. “We did this tour with Intronaut,” McCoy explains, “and it was really long and none of us were having that much fun. We became buds, and they kept us sane.” Following the tour, Dunable built McCoy’s instrument, which features a walnut body with a wenge fretboard and maple binding. It has just one knob—volume—and a Kahler tremolo unit sans locking nut.

“I never really have a problem with it,” McCoy says of the locking-trem design that first became a popular alternative to the Floyd Rose in the 1980s. “I’m not Kerry King [of Slayer, also a Kahler user]—I’m not holding up the guitar by the Kahler! I’m just using it for the Kevin Shields [My Bloody Valentine] stuff. It’s never gone drastically out of tune.”

McCoy’s Moonflower took the place of a rare blue Les Paul he used to favor. “Whenever people who know about guitars see it they’re, like, ‘I’ve never seen a Les Paul that color—and I’ve never seen one with a Kahler!’” But neither of these unusual features was a modification. “It’s some weird fluke from the early ’80s when everybody was starting to buy Jacksons. I guess Gibson wanted to try to compete with the dive-bomb market.”

Deafheaven co-guitarist Shiv Mehra also plays a Dunable. It has a Jaguar-style walnut body, a mahogany neck like the one on Dunable Moonflower models, a Gibson Burstbucker 2 in the bridge position, and a Fender single-coil in the neck position. “Shiv said, ‘I want mine silver—and I want the pickguard to be clear,’” McCoy laughs. “I was like, ‘God, you just want a guitar that looks like you do a shit ton of blow!’ It’s awesome.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)