The guitar-and-drums power duo is so common today that it’s easy to forget just how groundbreaking it seemed when the White Stripes steamrolled their way into the public consciousness in the late 1990s. Though not as widely known, Local H had been working as a two-piece since 1993, and, with the new millennium, the Black Keys emerged on the scene. Soon bands like Two Gallants, Japandroids, Wye Oak, No Age, Giant Drag, and many more were offering diverse manifestations of the duo format.

But in 1983, more than a decade-and-a-half before the Stripes released their eponymous 1999 debut, a young guitarist named Dexter Romweber and his childhood pal, drummer Chris “Crow” Smith, started bashing out a punky, adrenaline-fueled take on old-school rockabilly and blues in a North Carolina garage. Thus, the Flat Duo Jets were born. Though they had a bass player for a couple of years, for the great majority of their 16-year existence, the Flat Duo Jets were, as the name implied, a duo.

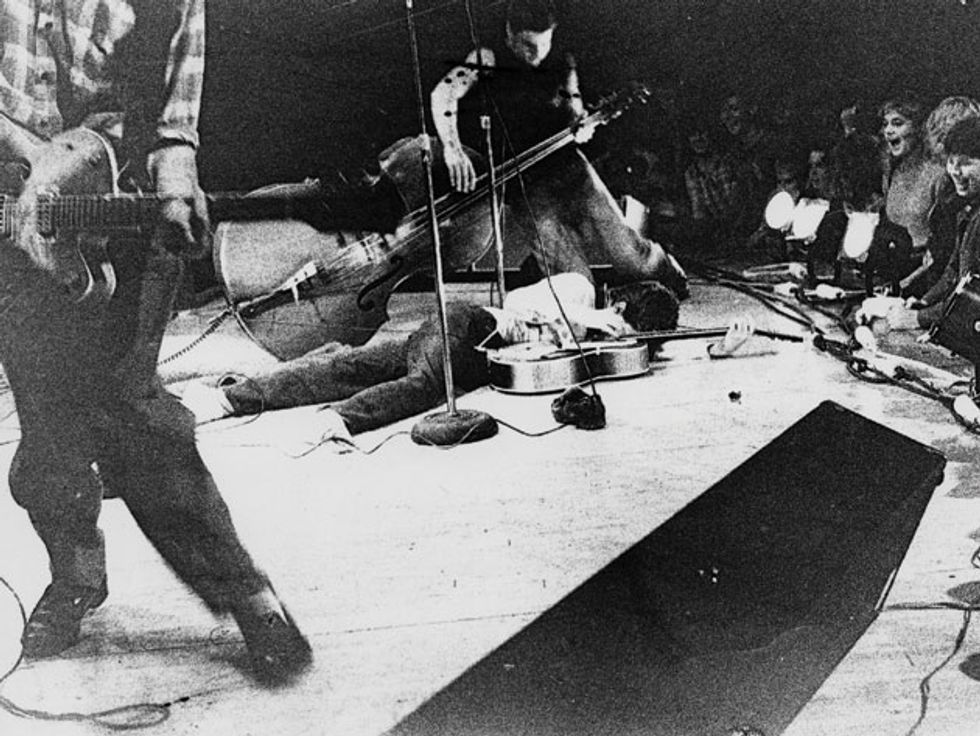

The Jets received quite a bit of critical acclaim and developed a fairly rabid cult following, and their incendiary live performances became the stuff of legend. But they never enjoyed widespread recognition or great record sales, and the toll of life on the road and inner-band turmoil led to the band’s demise in 1999.

Tony Gayton’s gripping 2006 documentary Two Headed Cow features quite a bit of footage from the band’s early years and heyday, not to mention some exceptionally moving scenes of post-Jets Romweber candidly discussing his struggles with alcohol, drugs, and mental health issues. The film also features heartfelt testimonials from artists who were influenced by Romweber—among them Neko Case, Exene Cervenka, Cat Power, Mojo Nixon, and Jack White, who selected Romweber (and his sister Sara on drums, performing together as the Dex Romweber Duo) to play the very first show at Third Man Records’ Blue Room in Nashville in 2010. Third Man has also released a couple of Romweber recordings.

Despite his lack of mainstream success, Romweber soldiered on, working the rock-club circuit and making great recordings along the way. And if you watch Two Headed Cow, it will be clear why he hasn’t given up. Music was never a career choice for Romweber. It is, very simply, a calling, the essence of his being.

Although he may not have the megawatt energy and barely contained fury he did when fronting Flat Duo Jets, he is still making great music. Case in point: His latest album, Carrboro (Bloodshot Records), named for Romweber’s North Carolina hometown, next to Chapel Hill. It’s one of his strongest efforts—a terrific collection of original songs and covers that seems like a snapshot of his entire career, from primitive rockabilly to haunting instrumentals to vintage-sounding surf to gorgeous ballads.

The haunting and ethereal “I Had a Dream,” written by Findlay Brown, a British-born singer-songwriter now living in Brooklyn, opens Carrboro. Like much of the album, the track demonstrates just how much richer and more expressive Romweber’s voice has become over the years.

In fact, it’s Romweber's singing that may be the album’s greatest revelation. Longtime fans know he’s a great and unique guitarist, and he can belt out punkabilly with a taunting, sneering growl as well as anyone. But it’s the more restrained and sensitive performances that show just how far he’s come as a vocalist, perhaps none more than his riff on the Charlie Chaplin song “Smile,” complete with a wonderfully eerie rubato piano accompaniment. (Although he’s known primarily as a guitarist, Romweber is a hell of a pianist, too.) And speaking of eerie, the excellent “Where Do You Roam?” has a dark, trippy secret-agent vibe, and shares some of the same menacing quality that Nick Cave has used to great effect.

Fans of instrumental music will find plenty to love. One of the album’s highlights is “Nightide,” a sinister romp through foreboding minor-chord changes that would be perfect over the opening credits for some film noir or grindhouse feature. Romweber turns the jazz standard “My Funny Valentine” into a twisted Tarantino-esque surf number by playing the melody on organ with no accompanying chords (and just a few guitar flourishes), stripping the song of its familiar context. “Out of the Way” is a particularly haunting reverb-and-tremolo-drenched piece that also begs for soundtrack placement.

Premier Guitar spoke with Romweber recently about the new album, life on the road, and his rich musical influences and compositions. Warning: If you’re a guitarist hoping to find tips on the latest boutique guitar or amp to help you achieve sonic bliss, look elsewhere. Onstage, Romweber has been playing pretty much nothing but Silvertone 1448 guitars through a 1982 Randall RG-80 solid-state amp since his last years with Flat Duo Jets—although he did play a Stratocaster and Jazzmaster through a couple of Fender amps on the new album. It’s further evidence that sound is more in the fingers and heart than in your equipment.

And if you’re hoping to find encouragement to start your new power duo, Romweber’s thoughts on the two-piece format just may surprise you.

Who were some of your early guitar influences?

“Big” John Taylor, definitely. He was the guitarist for [rockabilly artist] Benny Joy. And Hank Garland.

Flat Duo Jets were an aggressive, in-your-face band. There’s some of that on Carrboro, but it seems there’s more reflection and maturity. How have your approach and attitude toward music changed as you’ve gotten older?

The Duo Jets were primarily a rock ’n’ roll band. It was the strangest thing. Over time, we rarely practiced. With my sister, Sara, I practiced a lot more than the Duo Jets did. But often there were songs I wanted to do that Crow, the old drummer of the Duo Jets, wasn’t really into. And I kind of feel like now that I’m on my own, I can do everything I want to do—that I always wanted to do. It’s more freedom.

The Jets more or less started the duo craze, well before the White Stripes or the Black Keys. Were there other duos that you knew of or emulated?

I’ve got to be honest with you, man. I don’t even like duos. I don’t like the format. We started completely by accident as a duo. We just went in my mom’s garage and started playing, and that’s how it started.

But there are many things wrong with that format, I find, whenever I’m in them. And also, I’m a great fan of bass and I’m a great fan of sax and I’m a great fan of keyboards. I’m not completely putting down the duo format, but with two people, sometimes one was more dominant than the other, and then the other one was more dominant. There always seemed to be an imbalance. And then there was a magic night when both fell together. With the Rolling Stones, with five people, it would level out the sound more. And with duos, I always found there was some complexity about maintaining a good balance, and it was always frustrating.

And there are nights where one member might not be feeling it, and it’s more noticeable than it might be in a large band?

It’s a lot more noticeable, and the other person may be totally feeling it. So I don’t stand behind duos or even recommend it. And even with my sister, Sara, it was because we weren’t making enough money to add anyone else. With the Duo Jets it was a bit similar. You don’t make a killing doing this.

So you have some dates coming up. What is your touring band?

Well, I’m actually touring in a duo [laughs]! But it’s only a week, like four dates. But after that, it’s totally a solo tour for three weeks. Just me and my guitar. I like playing that way.

Do you play electric solo?

It is electric. But it’s not real loud. It’s not a blaring rock ’n’ roll show. That’s another thing I like, is not having to play so loud. My brain can’t handle the onslaught of really loud music anymore. I used to, but at this age—I turned 50 in June—I’m sort of in my Jackie Gleason years here a little bit. And also, I like soft music, too. I’m not putting down bands that blare away, but I’m not into it right now.

Known for wild performances in earlier days, Romweber is performing mostly solo these days, with just his Silvertone 1448. On a few select dates on his Carrboro tour, he’s backed by rock group New Romans.

Some performers assume a persona or sing a certain song from a character’s point of view, but it seems like you relate and feel every song personally on this album, and in general. Is what people see on the stage the real you?

I think so. I did songs that meant something to me. I did an interview right before you called, and he was asking about “Smile,” and I was telling him I had this big breakup the last couple of years, and I would play that song because it would make me feel better after having lost her, that no matter what happens you should smile.

Your piano accompaniment on that is really beautiful.

I don’t want to get too, well, narcissistic—that word is thrown around so much today—but there were many years where I wanted to be a classical pianist. I consider myself a failed classical pianist. I never took it as far as I really wanted to. And now I’m done with that whole sort of dream. But I still learned enough that I can do some things.

Growing old has its ups and downs, but one thing that happens for some people, and it’s definitely true with you, is that a voice can get richer and more expressive. I think your singing on this album is just phenomenal. How do you feel about your voice?

It’s a million cigarettes later, but yeah, I think with all the touring, and all the ups and downs of the business, you gain a lot of experience. A couple months ago, a friend played me some really early recordings, and I turned to him and said, “It sounds too white [laughs].” And I really meant that! It sounded so naive, and so white. I hadn’t been through enough. I can agree with you, that the harder knocks you take, and the longer you survive, you have more to convey.

Dex Romweber’s Gear

Guitars

• 1964 Silvertone 1448

• Fender Stratocaster (album only)

• Fender Jazzmaster (album only)

Amps

• 1982 Randall RG-80

• Various Fenders (album only)

Strings and Picks

• Ernie Ball (.010–.046)

• D’Addario (.010–.046)

• Dunlop Orange Tortex .60 mm

Your vocal performance on the opening track, “I Had a Dream,” is stunning. I’d never heard of the songwriter, Findlay Brown. How did you come across that song and what made you want to lead the album with it?

My old roommate came home and said, “I heard this really trippy song.” And I think he bought the CD. I really, really liked the song. It wasn’t a massive hit for Findlay. But the song touched me, and that’s the reason I recorded it. I hope Findlay doesn’t mind.

I tried my best to find out what I could about Cecelia Batten, who wrote “Lonesome Train,” and there’s very little information online.

There is no information.

So how did you come across the song?

I found “Lonesome Train” in a second-hand store in Carrboro in the ’80s. And I learned the tune and always played it, but never recorded it. So it was my chance to cut “Lonesome Train,” and I’m glad I did.

I love the reverb-drenched electric guitar in the background of “Lonesome Train,” which makes it sound a little demented in a really cool way.

It’s a 1448 Silvertone, but I knew what tone to put on it for that one. I turned down all the treble. I think it was plugged into a Fender amp.

Are you still playing the same Silvertone you played in the early years?

No, it’s probably my 13th one or something [laughs].

The instrumental “Nightide,” which you wrote, sounds like it should be the soundtrack for True Detective or a David Lynch movie.

Yeah, I think of David Lynch a lot when I hear it. I hope it makes it to any of those things.

Have you had any luck with placement in film or TV?

Not much. A few things have come in, but not in 15 years. No one’s really called about anything.

What inspired you to do “Trouble of the World?”

I heard that on a commercial on TV for a Mahalia Jackson record. And I thought, “Wow, what a trippy song, man.” I was blown away by it. And then I found the original and took it from there. I know some other gospel artists cut it. The thing about that song is, it’s primarily a song about the black experience in America. But I’d had enough hard luck to identify with it.

Tell me about “Knock Knock (Who’s That Knockin’ on My Coffin Lid Door?),” which you recorded with Rick Miller of Southern Culture on the Skids. It feels like a throwback to the Flat Duo Jets days.

Someone asked me yesterday how I write songs. And it’s almost a psychic, meditative process. And that’s another song I heard completely in my mind, including the electric guitar line. It’s really simple. But I already heard it.

I mean, I’m not comparing myself to Nikola Tesla, but I know that when he invented something, he would see it in his mind before he did it. And that’s a lot of my process. It’s the same with “Where Do You Roam?,” “Midnight at Vic’s,” and even “Out of the Way.”

“Out of the Way” has a really dreamy, haunting quality.

This is something you can’t really escape when you’re making a record. And this is why a lot of my records sound really different. The vibe of your life is what’s going to be on tape. So when I cut “Out of the Way,” I was in a very strange mental place and there’s a lot of struggle, and there’s all these weird things going on that I have to deal with outside of music. And when I cut it, of course, all that vibe, where you’ve been, is right there on tape. You can’t escape where you’ve been and how you feel.

Do you ever listen to a song like that and think, “Well, that week may have sucked, but at least it inspired that song?”

Yeah. And also, you move on from that period, and you’re like, “Wow, I’m not even there anymore, and I only cut this song a year ago.” There are some of my records it took me 13 years to even like, because the times when they were recorded were so fucked up. But over time for me, I’m less judgmental and harsh on the stuff I’ve cut.

“Tell Me Why I Do,” which you wrote, reminds me of some of Jerry Lee Lewis’ country stuff.

It does, but it was really Ray Charles. I grew up on Ray, too. I’ve always loved Ray Charles. Each song has a little flavor of an artist I really admire. “Midnight at Vic’s” is supposed to be kind of an Eddie Cochran thing, which is kind of weird. You can’t be in this business without being influenced by all these artists. “Knock Knock” is almost a George Jones rockabilly thing, when he cut rockabilly.

The film Two Headed Cow is 10 years old already. After people like Jack White or Cat Power or Exene Cervenka were talking you up, did you notice any increase in your fan base?

I never really have. Very little. A month or so ago, I needed cash, so I called Jack’s record company. And I said, “Listen guys, can you send me some money?” And they did. That’s a real plus. Me and Sara cut a record with Jack, and they re-released some Duo Jets stuff. He put me and Sara in New York City in front of Wanda Jackson, at a really big concert. And he put us on the road with Wanda. But it’s rare that I meet people that come out because of him. I imagine they’re out there.

Do you find touring has gotten easier or harder with age?

It’s never gotten any easier [laughs].

YouTube It

The Dex Romweber Duo—Dex on guitar and his sister, Sara, on drums—powers through the classic “Brazil,” written by composer Ary Barroso. Dex steps up for a solo on his Silvertone 1448 at 1:15, kicking in with ringing single notes and culminating with chugging choked-and-released seventh chords before riffing to the finale.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)