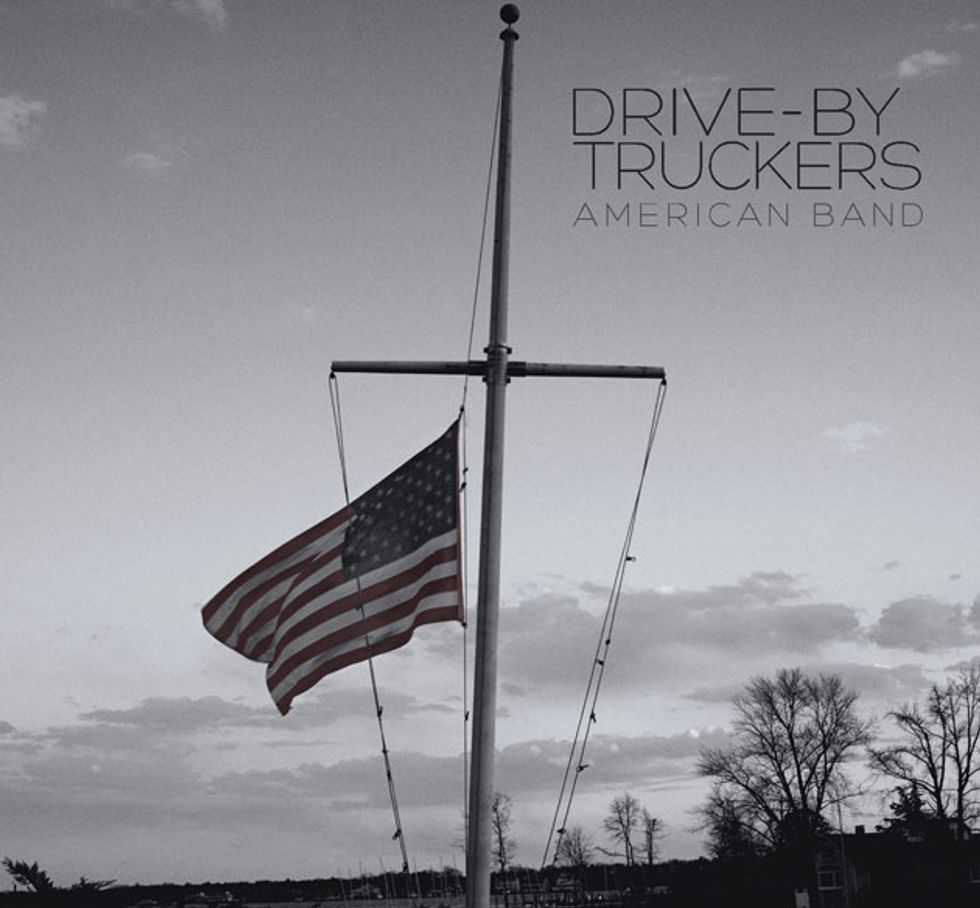

You could think of American Band, the new release from Drive-By Truckers, as a compelling collection of passionate, guitar-centric Southern roots-rock by one of the genre’s leading torchbearers, which it certainly is, but it’s also something much deeper than that. Taken in its entirety, American Band could be seen as a barometer of how much—or perhaps more to the point, how little—our nation has progressed since DBT’s cofounders Patterson Hood and Mike Cooley dug deep into the culture wars and the politics of race 15 years ago on Southern Rock Opera, the band’s ambitious and critically acclaimed third studio album.

Southern Rock Opera focused on the complexities and contradictions of what it means to be a Southerner, filtered through a fictionalized account of the Lynyrd Skynyrd story. And while the new album tackles elements of Southern identity—most notably “Ever South,” in which Hood reflects on the ways his Dixie roots have followed him across the nation to his new home in Portland, Oregon, and “Surrender Under Protest,” Cooley’s takedown of folks who still haven’t given up the cause of the Confederacy—American Band, as the title suggests, is in large part an examination of the entire nation’s identity.

The jump from a regional to national focus makes sense. As we have been reminded over and over again in recent years, the South has no monopoly on racism, the fetishization of guns, or religious hypocrisy. And while some artists prefer to keep their political leanings close to their vests for fear of alienating potential fans, that’s never been the case with Drive-By Truckers, a decidedly left-leaning band raised on right-leaning soil. In fact, American Band is the Truckers’ boldest political statement yet, and could be seen as a rallying cry, released just a few weeks before one of the most contentious presidential elections in the nation’s history. Hood and Cooley recently discussed the new album with Premier Guitar by phone from their respective homes in Portland and Athens, Georgia.

A primary theme of American Band is gun violence, usually with racial implications. Four of the album’s 11 tracks deal with guns. “What It Means” addresses the rash of killings of young unarmed black males by police through the lens of the Michael Brown shooting in Ferguson, Missouri. Over a hypnotic two-chord vamp, Hood ponders the limits of civil rights progress, and sums up the situation with two simple lines:

I mean, Barack Obama won and you can choose where to eat

But you don’t see too many white kids lying bleeding in the street.

“I think that if the only people saying things like ‘Black lives matter’ are black people,” Hood says, “there’s not going to be as much progress made as when everyone starts saying things like that, and talking about the problem. Talking about it is not always pleasant—we all have that uncle at Thanksgiving who says terrible things. And I think that’s where we are right now: I think our country is in the midst of a really uncomfortable Thanksgiving dinner. It’s been coming for a long time.”

Cooley’s song “Ramon Casiano” is about Harlon Carter, who, when he was 17, shot and killed the titular 15-year-old Mexican boy. Carter was convicted of murder, but the conviction was later overturned on appeal, and 47 years later he became executive vice president of the NRA. (Carter was a key player in the Cincinnati Revolt of 1977, a dramatic coup in which gun-rights radicals took control of the NRA, transforming the organization from what was a relatively bipartisan group focused on hunting and marksmanship into the fiercely right-wing political lobbying group it is today.) Carter has been dead for 25 years now, but his checkered legacy is as relevant as ever.

“Growing up in rural, working-class Alabama,” Cooley says, “it’s a culture of people who like their guns. But it had never been a political thing before. It was in the early ’80s that I distinctly remember thinking, where did all this ‘they’re coming for your guns’ business come from all of a sudden? ‘The government is buying all the ammunition so we can’t have any, so you better go stock up!’

Mike Cooley with his Cooleycaster, luthier Scott Baxendale’s take on a vintage Tele. Photo by Tim Bugbee — Tinnitus Photography

“Carter was convicted [of killing Casiano], but he never served any time, and no one knows specifically why. More than likely it was small-town Texas in the 1930s. A white boy killed a Mexican and nobody gave a shit.”

Two more of Hood’s songs also focus on gun violence: “Guns of Umpqua” and “Darkened Flags on the Cusp of Dawn.” The first is about the October 2015 mass shooting at Umpqua Community College, near Roseburg, Oregon, which left an assistant professor and eight students dead. Though mass shootings are, sadly, fairly commonplace these days, the Umpqua shooting had particular resonance for Hood, who had passed through the town where the college is just a few months before, as he and his family were on their way to their new Portland home.

Hood was sitting on his front porch having coffee when he learned of the shooting. “It was one of those gorgeous fall days, blue skies,” he says. “What makes someone wake up on a morning that’s so nice, and go out and ruin a lot of people’s lives, and make an entire community, and country, mourn and grieve? One of the guys shot had been a veteran—he had been in one of the Mideast wars. My God.”

Hood wrote “Darkened Flags on the Cusp of Dawn” in response to the Charleston church shooting last year that left nine African-Americans dead at the hands of 21-year-old white supremacist Dylann Roof.

“It all ties in with what we named the record, American Band, and [the image of a flag at half-mast on] the album cover, because it seems like more and more, when I see a flag, it’s flying at half-mast,” Hood says. “That’s just where we seem to be right now.

“And yet in South Carolina,” he continues, “where this horrendous thing happened, the fucking Stars and Bars were flying at the top of the pole.”

At the same time Hood was writing the song, he was asked to write an op-ed for The New York Times Magazine. “Being known as this writer of Southern things, and Southern Rock Opera, I got asked to write about the flag,” he says. “I think the [pro-Confederate flag argument] got lost somewhere around the time when they were flying them at a Klan rally or a lynching. That made it synonymous with what the Nazis did to the swastika. It was something that predated the Nazis, but it will never, ever not be viewed through that lens again.”

The Charleston church shooting also served as fodder for one of Cooley’s songs, “Surrender Under Protest.” “The shooting brought back the whole Confederate flag business,” he says. “And the thing about that is, what the flag means to you doesn’t change what it is. And what’s being referred to [by Confederate flag supporters] as ‘political correctness’ is what my Southern, white, Christian, hard-working grandparents taught me was just common decency.”

Patterson Hood playing “Snakes,” his custom Baxendale archtop electric that was inspired by a vintage Silvertone 1446. Photo by Tim Bugbee — Tinnitus Photography

On “Kinky Hypocrite,” Cooley takes on culture-war profiteers. At the end of each verse, he sings a couplet that drives home the song’s message:

The greatest separators of fools from their money

Party harder than they like to admit.

Cooley says the song was inspired by former Alabama Supreme Court chief justice Roy Moore, who gained notoriety for refusing to remove a monument of the Ten Commandments he had commissioned from the grounds of the Alabama Judicial Building, as well as by various conservative firebrands who have wound up getting caught (in some cases literally) with their pants down.

“It’s always the guys who are the most anti-gay and vocal about it who get caught picking up dudes in bathrooms,” Cooley says.

On “Ever South,” Hood explores his native region on a personal level—particularly how his Southern roots have been magnified by his move to Portland. He sings:

So we aimed our sights westward like so many did before

Expanding our horizons to some distant shore

Where everyone takes notice of the drawl that leaves our mouth

So that no matter where we are we’re ever South.

“It’s funny, because I kind of swore I would never write that kind of song again,” Hood says. “Because after Southern Rock Opera, for years, people would refer to us as a Southern rock thing, and I kind of hate that. That’s not how I pictured it. I always thought of that as something that happened in a specific place and time, and we wrote an album about that place and time.”

Ultimately, the song is more about leaving the South than about the region itself. “I miss my friends and family, and they’re a long way away,” Hood says. “But I also really love where I’m at. And I love the effect it’s had on my own family and on my writing and on my day-to-day life. I think as a piece of writing, it’s one of the best songs I’ve ever written. I’m extremely proud of every line and how it all fits together.”

Things get even more personal on “Baggage,” a song about depression that Hood wrote the night Robin Williams died. “He’s someone who makes us laugh, and forget our troubles,” Hood says. “And of course, comedians are famously depressed, and that’s where so much of the comedy comes from. I’ve had my own bouts with depression. And our band’s pet cause has always been Nuçi’s Space, which is a suicide prevention nonprofit based out of Athens. They do amazing, really innovative things. We’ve done benefits for them every year of their existence, and will continue to.”

Hood was sitting outside a bar in Athens having drinks with friends when he heard the news about Williams, and immediately felt compelled to start writing a song. “I could just hear it on the radio in my head,” he says. “So I grabbed a sheet of paper and wrote the majority of it down then. And the next day I sat down with my guitar and actually finished it and put it all together. It seemed like a natural piece of the puzzle for this record, and the place where it needed to end.

“Even though the record has a lot of the political in it,” he continues, “it’s always about the personal. Because the political is personal. People say, ‘Shut up and sing! Don’t be talking politics. It’s dragging me down!’ But it’s all tied together. Before Obamacare, I had issues getting all of my family insured because of preexisting conditions. And so that’s a place where something political was very, very personal to me, and continues to be.”

The political and cultural critiques and personal reflections put forth on American Band are so impassioned that it might be possible to overlook the music, which would be a mistake. The opening track, “Ramon Casiano,” is a shining example of roots-rock guitar, and serves as a great case study of the Truckers’ ensemble aesthetic. Cooley kicks the song off with a grand, heavily overdriven rhythm guitar figure that propels the tale. Utility man Jay Gonzalez, who contributes both keyboards and guitar in the studio and onstage, plays a beautiful melodic guitar line after the first verse, than further develops that motif after the second verse. After the bridge, Hood takes his turn with a brief but melodic lead, with a hint more reverb. Then on the outro, Cooley rips out a few heroic, grinding riffs that feature some pedal-steel-inspired bends, albeit with a healthy dose of tube distortion.

Drive-By Truckers' Gear

Guitars and BassesFender Thinline Telecaster

Fender Jazzmaster

Fender Precision Bass

Gibson SG Special

Amps

Fender Deluxe Reverb

Goodsell Black Dog 50

Marshall 1974X Handwired 1x12 combo

Marshall 2061X Handwired Lead/Bass

Sommatone Roaring 40

Ampeg V-6B

Steve Ace of Clubs combo

National Valco 1212 Chicago 51 combo

Demeter Tube Direct DI

Effects

Boss SD-1 Super OverDrive

Lumpy’s Tone Shop 7 Series Lemon Drop Overdrive

Strymon El Capistan dTape Echo

Prescription Electronics RX Overdrive

Accessories

Fishman Matrix Pickup

In their conversations with Premier Guitar, both Hood and Cooley had a hard time recalling who played what on many of the tracks, though as a general rule, Hood’s parts feature more reverb—he plays through a reissue ’63 Fender Tube Reverb unit plugged in to his 1972 Deluxe Reverb amp—and Cooley’s parts are typically dry. But throw Gonzalez into the mix—sometimes he’s got reverb, sometimes he’s dry—and at times it’s anyone’s guess which guitarist is playing. And that’s only fitting, since the Truckers are a true guitar democracy.

Most of the music on American Band has the energy and immediacy of a group cranking it out in a club, with little in the way of studio gimmickry. “Probably 90 percent of everything we’ve recorded has been more or less live in the studio,” Hood says. “On this record, I think it’s almost 100 percent. There’s a couple of songs where I think we even used Cooley’s scratch vocal take. We might go in and redo the vocal or overdub a guitar track or two. We made this record in six days—that’s overdubs and everything—which I think is the fastest record we’ve made since Pizza Deliverance in ’99.”

Though DBT’s two- and sometimes three-guitar attack and region of origin—not to mention their album Southern Rock Opera—might lead them to get lumped into the Southern rock genre, it’s not really an accurate classification. Typically, Southern rock features extended (and often overindulgent) guitar solos, and those solos sometimes include repetitive licks that have been beaten into the ground.

There may be an abundance of electric guitar on American Band, but it is all in the service of the songs. Solos are typically concise and melodic. “Darkened Flags on the Cusp of Dawn” features a distinct, forceful opening riff that recalls vintage Crazy Horse. “Surrender Under Protest” starts off with a brief but triumphant melody that recurs through the song. The guitars on “Kinky Hypocrite” have the strut and swagger of Sticky Fingers-era Stones—in fact, it almost sounds like Keith Richards and Mick Taylor sat in on the session. Elsewhere—“Guns of Umpqua,” “What It Means,” “Once They Banned Imagined”—acoustic guitars figure prominently. (For a detailed, song-by-song account of the gear used on the album, see “A Truckload of Toys” sidebar.)

American Band is among the finest work yet from Drive-By Truckers, which is saying something for a band that’s been around for 20 years and has released 11 albums. Hood and Cooley are the only original members, and there have been several lineup changes over the years, not to mention a few bumps in the road dealing with inner-band drama. Jason Isbell was a Trucker for six years and three albums, from 2001 to 2007. But right now, DBT seems to be firing on all cylinders, and both Hood and Cooley feel their current lineup is the strongest yet.

“It’s great,” Cooley says. “The band is drama-free. Everybody, including myself, is really invested right now—more than I’ve ever felt.”

And Hood couldn’t agree more. “This is our fifth year now with this lineup, which is the longest we’ve ever gone without a single personnel change,” he says. “It’s my dream band—my favorite band I’ve ever had or even imagined having. We have a lot of fun, laugh a lot, play great together, and have a wonderful musical chemistry. They’re so supportive of the songs that I write, the songs that Cooley writes. It’s really pretty magical.”

A Truckload of Toys

Ace guitar tech DeWitt Burton breaks down the gear used to record DBT’s new album, American Band.You may not know the name DeWitt Burton, but there’s a good chance he’s had a hand in creating some of the music you’ve heard, both on record and onstage. Whether serving as a guitar tech, consulting on backline, or managing equipment and production, the Athens, Georgia, resident has worked with some of the biggest acts of the last three decades—including Son Volt, Elliott Smith, Bruce Springsteen, Sheryl Crow, Big Star, Lucinda Williams, the Police, Wilco, Widespread Panic, the Black Keys, and, most notably, R.E.M., for whom he’s been a full-time employee since 1999, caring for a warehouse full of the iconic quartet’s instruments and recording gear, and also assisting on the bandmembers’ various solo projects.

For the last couple of years, he has also been working with Drive-By Truckers, and he was tending to all of the guitars and amps—and with three guitarists, that’s a handful—during the recording of American Band. (Somehow, he also manages to find time to work with renowned Athens guitar maker Scott Baxendale, who has built or restored several of the Truckers’ main axes.)

Burton is a fastidious record-keeper in the studio, and he shared his copious notes regarding the guitars, basses, amps, picks, effects, and strings used to record the basic tracks for American Band. Burton says he can’t be 100 percent sure what was played on every song, and some overdubs are not included. Still, for guitar players and gear geeks of all stripes, it provides a fascinating chronicle of six days in the studio with the Truckers making one of the best albums of 2016. And it demonstrates the passion, knowledge, and attention to detail required to be a world-class guitar-tech. (On a related note, Patterson Hood informs us that for the most part, the Truckers’ guitars and basses are tuned down a whole-step from standard tuning to D–G–C–F–A–D.)

Now, in Burton’s own words, here’s the lowdown on American Band gear.

“Ever South”

Matt Patton played his Fender Precision bass. He strings all his basses with flatwound D’Addario Chromes, gauged .045-.100. When not plucking strings with his fingers, Matt uses a Dunlop 1.14 mm Tortex standard pick. All his bass parts went through a vintage Demeter Tube Direct DI into his trusty Ampeg V-6B solid-state amplifier. That thing is so versatile. He used the head to dial up some grind—which it does so well. The Ampeg drives an old Kustom ported 2x15 cabinet. I can’t remember what speakers that was loaded with.

Patterson is pretty much dialed into what he wants. You have to remember these guys have been at it a while. He knows what works for his attack, and when it comes to tone, he believes in “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” He played his “baby” on this track—a 1930s Gene Autry Melody Ranch acoustic guitar sold by Sears and Roebuck as part of their Supertone line. The original inside label read: “This instrument is guaranteed to be free from defects and flaws and to comprise the best materials and workmanship and tone that is possible for the price.” It has a solid spruce top and mahogany back and sides. It was made at the Chicago Harmony factory.

The guitar underwent Scott Baxendale’s Harmony conversion process that includes resetting the neck, replacing all the bracing with proprietary internal bracing (loosely based on a 1938 Martin), replacing the bridge and bridge plate, refretting, and replacing the tuners. Full disclosure: I work in Scott’s shop doing repairs when I am not on tour or preparing for one. This guitar was one of the finest examples of the conversion process to come out of the shop, in my opinion. It was strung with D’Addario’s new Nickel Bronze acoustic guitar strings, gauged .011–.052. Those strings are the shit! The guitar has a Fishman Matrix under-saddle transducer pickup. It ran through a reissue stand-alone Fender ’63 Reverb unit into “Fred”—Patterson’s longtime silverface Fender Deluxe Reverb. Patterson uses .65 mm gold Herco Nylon Flex 50 HE210P guitar picks. No pedals, just natural tube distortion. This setup is testament to good ol’ Yank ingenuity and craftsmanship, and is as American as a Chevrolet Impala.

For the overdub, Patterson used “Snakes,” his custom Baxendale 16" archtop electric. It has maple sides and back with a spruce top, maple neck, and ebony fretboard. Inspired by the Silvertone 1446 (commonly known as the Chris Isaak model), it’s not exactly hollow or semi-hollow, but has a sound post block that couples the back and top. This gives it its magic when playing with feedback. It has a 24.75" scale and has Seymour Duncan Antiquity pickups. He ran it through the identical Fender Reverb /Deluxe Reverb chain as above, but with different settings, of course. It was strung with D’Addario EXL115 Nickel Wound Mediums (.011–.049).

Mike Cooley also picked acoustic guitar on this basic track. He used his custom Baxendale Superlative model with an Engelmann spruce top, mahogany sides and back, mahogany neck, and ebony fretboard. The body shape resembles a Martin dreadnought with a single cutaway. However, it’s only 2.25" thick at the heel. According to Baxendale, “The thin body gives a more even response, especially across the low end, without sacrificing volume or headroom. As in all my acoustics, it has my proprietary scalloped and tuned bracing.”

The Superlative has a 25.5" scale, a Fishman Matrix pickup, and was strung with those D’Addario Nickel Bronze strings (.011–.052). We ran it through a Silvertone 1483 bass amp into an A Brown Soun 2x12 open-back cabinet loaded with alnico Tone Tubby Hempcone speakers to warm up the signal. No pedals, just natural tube distortion.

For the overdub, Mike used his mid-’80s Gibson Corvus—the model with one P-90 pickup in the bridge position. It had D’Addario EXL115 strings and ran through the same amp and cabinet setup with different settings. Mike uses gray .88 mm Dunlop 449R Nylon Standard picks.

“Darkened Flags on the Cusp of Dawn”

Patterson played his SG into his ’63 Fender Reverb unit and silverface Fender Deluxe Reverb rig. He also used a Boss SD-1 Super OverDrive pedal.

Mike played his custom Baxendale Cooleycaster, which is Scott’s take on a vintage Tele. As Scott explains, “I wanted to make a guitar that looked like a traditional design, but was uniquely different, too. The Cooleycaster has a basswood body with a curly maple top. Its curly maple neck has a 1.75" nut width and a deep V shape, and the fretboard markers are mother-of-pearl inlaid into ebony, which is then inlaid into the maple. The guitar has a Seymour Duncan Seth Lover in the neck position and Duncan Hot Rails at the bridge. I built it in 2006, I believe.” Mike ran straight into a Richard Goodsell Black Dog 50 connected to a ’80s Marshall 4x10 1965A cabinet.

When it comes to tone sleuthing, Jay Gonzalez is his own man. He played his 1968 Gibson SG Special outfitted with a Baxendale Vibrola mod that basically applies the Paul Bigsby design of a rocking bridge to a Gibson ABR-1 Tune-o-matic. It makes the Gibson Vibrola usable and requires no modification to the body. Jay’s signal ran through a Lumpy’s Tone Shop 7 Series Lemon Drop Overdrive into a Strymon El Capistan dTape Echo pedal, then out to an ancient National Valco 1212 Chicago 51 tube combo amp. His guitars also sport D’Addario EXL115 strings, and, like Patton, he uses a Dunlop 1.14 mm Tortex standard pick.

“Baggage”

Matt used the same bass rig on everything. However, on this song he swapped his P bass for a late-’50s or early-’60s Spiegel-era Kay single-cutaway semi-hollowbody bass with a single DeArmond Speed Bump pickup. Patterson played his early-21st century Gibson SG through his Reverb/Reverb rig. Mike played the Cooleycaster through an 18-watt Marshall 1974X Handwired 1x12 combo. No effects for anyone; only tube-amp generated harmonic distortion.

“What It Means”

Patterson played his Melody Ranch through his Reverb/Reverb setup, and again Matt tackled this song with his Kay. Mike played his Thinline Telecaster through a Jack Brossart Prescription Electronics Vibe-Unit on the chorus setting. The amp was a 20-watt Marshall 2061X Handwired Lead/Bass head driving a ’80s Marshall 4x10 1965A cabinet.

“Where the Sun Don’t Shine”

Matt on his Kay bass again with Patterson playing his SG through his Reverb/Reverb rig. Mike played a late-’90s Gibson SG Special into that Marshall 2061X Handwired 4x10 half-stack.

“Surrender Under Protest”

Matt on P bass with Patterson on the Baxendale “Snakes” hollowbody electric through his standard setup. Mike played a late-’90s Japanese-made Fender Jazzmaster Classic Player. I really like those guitars. They have a deeper neck pocket than the American Vintage ’65 Jazzmaster Reissue. The pickups are totally different—darker and harsher than the American ones. It also has a Nashville Tune-o-matic-style bridge with the Baxendale Gibson Vibrola mod. (Though designed to improve the Gibson Vibrola, the mod also works for the Jazzmaster trem, but not as well as the Mastery Bridge.) He plugged this into his wall-shaking Sound City 50 Plus (with both channels bridged and cranked) and drove that ’80s Marshall 4x10 1965A cabinet nearly to extinction. It sounded heavenly.

“Ramon Casiano”

Matt used the P bass, Patterson played “Snakes” through his beloved Reverb/Reverb setup, and Mike plugged the Jazzmaster straight into the Marshall 1974X Handwired combo.

“Guns of Umpqua”

Matt played the Kay bass with Patterson on the Melody Ranch acoustic through his Reverb/Reverb rig. Mike ran the Cooleycaster into a Danelectro Reel Echo pedal (his Echoplex was too noisy for this track) and out to the Sound City 4x10 half-stack mentioned earlier.

“Filthy and Fried”

The basic track was cut live during soundcheck at the 40 Watt Club in Athens during the band’s 2016 Homecoming Weekend shows. Matt was on his P bass; Patterson played a goldtop 1969 Gibson Les Paul Deluxe (in standard tuning) through his pedalboard and into his bread-and-butter Reverb/Reverb setup. Mike played either the Jazzmaster or the Cooleycaster through his Sommatone Roaring 40 head and matching 2x12 open-back cabinet. I know he was using the Prescription Electronics RX Overdriver because I put it on his board that day. He used it all weekend.

“Kinky Hypocrite”

This was recorded in just a handful of takes late at night. Mike played his Cooleycaster through the Marshall 1974X combo. The band had finished tracking a different song several times and had retired to the control room to listen back. They were pleased with what they heard and I mistakenly thought it was the end of a long day of recording.

While I was out in a workshop off of the main room restoring a Univox Super-Fuzz pedal, I think a few adult beverages were consumed and some stories were told in the control room. All of a sudden, the band came roaring back into the studio, picked up whatever was sitting in front of the amps, and just went for it. The song was finished, complete with overdubs, in about two hours.

“Once They Banned Imagine”

Mike played his Baxendale Cooley Custom Acoustic, which is affectionately known as the CooleyBird due to the Wes Freed artwork on the top. [Editor’s note: Since painting the cover for 2001’s Southern Rock Opera, Freed has done virtually all the artwork for Drive-By Truckers.] I think Patterson was running his SG through the Reverb/Reverb rig with a Seymour Duncan Pickup Booster in the signal chain to add a little more sparkle to the parts he was playing lightly.

YouTube It

This studio performance of “Ramon Casiano”—one of the songs from American Band—offers a great example of how the Drive-By Truckers share lead guitar duties. At different points in the song, Jay Gonzalez, Patterson Hood, and Mike Cooley each take a solo.

The Truckers reveal their acoustic side in this three-song set recorded at NPR. Throughout this performance, Patterson Hood strums his 1930s Gene Autry Melody Ranch flattop while Mike Cooley picks his Baxendale CooleyBird, which sports artwork by Wes Freed.

Check out the Rig Rundown we filmed with DBT in 2015 where we detail all the gear used by Mike, Patterson, and Jay.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)