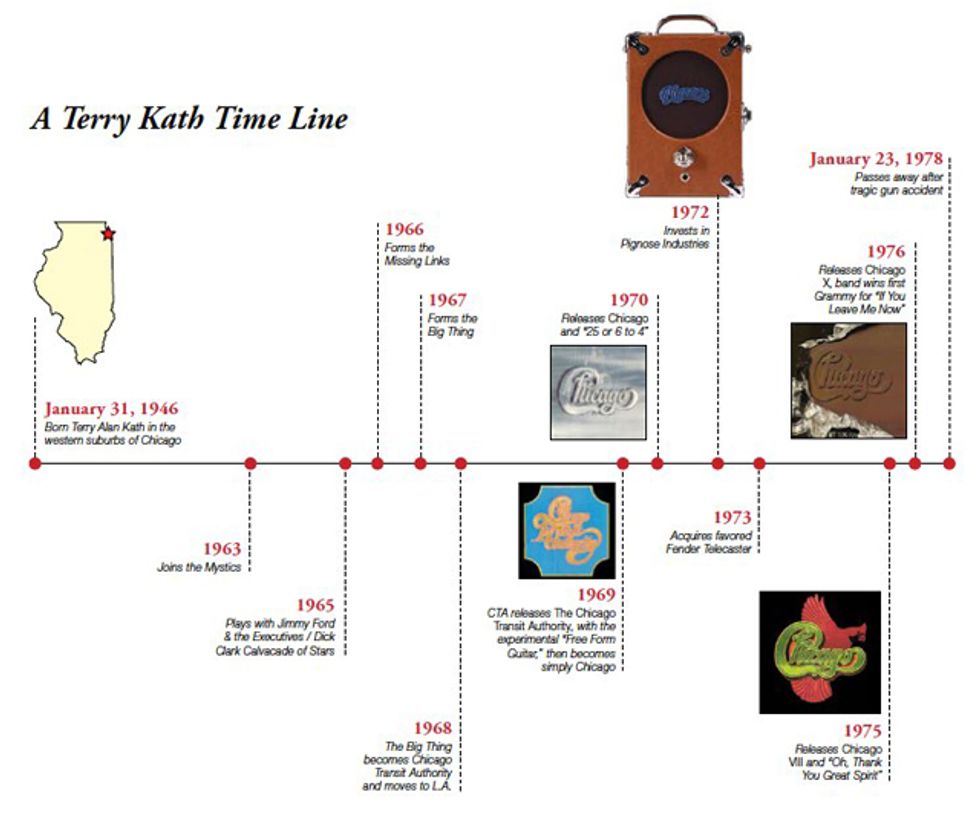

Born: January 31, 1946

Died: January 23, 1978

Best Known For: A founding member of Chicago—one of the first rock bands to incorporate a horn section—Kath helped forge a path for this band that included eight platinum albums in as many years. In addition to penning many of the group’s songs, his inventive solos purportedly impressed Jimi Hendrix enough for him to tell Chicago’s saxophonist Walt Parazaider, “I think your guitarist is better than me.”

In 1968, the Chicago Transit Authority found themselves playing a show at the renowned L.A. club the Whisky a Go Go. The gig itself was unremarkable, just another in a long series of dates they’d been playing since changing their name from the Big Thing. It was what happened after the show that made this evening memorable for the group—and especially for their guitarist. According to the band’s saxophonist Walter Parazaider, after the show, “This guy came up very quietly and tapped me on the shoulder. He says, ‘Hi, I’m Jimi Hendrix. I’ve been watching you guys and I think your guitarist is better than me.”

The guitarist Hendrix was referring to was Terry Kath, and whether or not the above story is true or apocryphal is immaterial: The fact that one could hear Kath and then judge the story plausible matters as much as its authenticity. And among those who either witnessed his prowess firsthand or came to know it after his untimely demise at the age of 31, it is virtually unanimous that Kath is one of the most criminally underrated guitarists to have ever set finger to fretboard. Give a listen to what many consider to be Chicago’s signature song, “25 or 6 to 4,” one is instantly transfixed by the punch of the chromatically descending opening riff, the funky fills, the slippery licks, and the tones that range from wooly fuzz to searing, wah-inflected colors.

Kath dedicated his life to making music, but as the years wore on the grind of longer tours and greater expectations took a toll. He became increasingly unhappy and on January 23, 1978, he put what he thought was an unloaded gun to his head and pulled the trigger, ending his life. Though he is gone, his incredible talent certainly isn’t forgotten.

A Mystic

Terry Alan Kath was born on January 31,

1946, to Ray and Evelyn Kath in the western

suburbs of Chicago. Terry was enamored

with music at a young age and with

the encouragement of his parents he quickly

learned how to play drums, accordion,

piano, and banjo. His childhood friend and future bandmate Brian Higgins was quick

to observe in an interview with Chicago-area

music chronicler Tim Wood that,

“From the eighth grade on, Terry knew he

was going to be a professional musician.”

Like many youths from that era, it was only a matter of time until he discovered the guitar. Kath’s first rig consisted of a basic guitar and amp made by Kay, and he spent hours practicing on it in the comfort of his basement. Only once did he attempt to get professional lessons, but it didn’t go as well as he hoped, as he recalled in a 1971 interview with Guitar Player: “He just kept wanting me to play good lead stuff, but then all I wanted to do was play those rock and roll chords.”

Over time, Kath’s playing chops developed and he linked up with a group of his high-school buddies to form a band called the Mystics. Kath soon became the focal point for those who came to see the Mystics play, and he became the de facto leader of the group. The band tooled around Chicago’s many dance halls, clubs, and Veterans of Foreign Wars halls, playing one or two shows a week, and quickly built a dedicated following. Kath had a deep love of jazz, which inspired him to spurn the solidbody Gibson and Fender guitars popular amongst players of the day, Instead, he elected to play a Gretsch Tennessean. “He did a lot of work on that guitar. No one but him could play it without it buzzing,” recalled Mystics rhythm guitarist Brian Higgins.

After a few years in the Mystics, Kath left the group and joined up with Jimmy Ford & the Executives, where he was asked to switch to bass. The Executives were one of the most talked-about groups in Chicago and served as a road band for Dick Clark’s Cavalcade of Stars—which featured such noted artists as Little Richard, Chuck Berry, and the Yardbirds. Kath proved to be a valuable member, and as future Chicago drummer and Executives band member Danny Seraphine wrote in his memoirs, “He was the closest thing to a leader in the band in terms of the direction of the music.”

Kath’s time with Ford and the Executives was as hectic as it was brief. Along with Danny Seraphine and Walter Parazaider, Kath was shown the door when the group decided to join up with an R&B horn outfit and take the music in a new direction. It didn’t take long for Kath and his exiled bandmates to find a new group, and in short order they found themselves playing in a cover band called the Missing Links. The band was led by Parazaider’s childhood friend Chuck Madden, whose father was known locally for being a big-time booking agent. Owing to that boon, Kath soon found himself earning more money per week than ever before—a whopping $500.

The Missing Links tore up Chicago’s club scene and regularly drew large crowds eager to hear hits of the day performed live and in person. But the grind of regularly playing other artists’ songs over and over, night after night, began to wear on Kath. As audiences began to dwindle and as the band members’ talent grew, the Missing Links decided to call it a day. Out of the ashes, Seraphine began forming ideas for a new outfit and invited Kath and Parazaider to join him in what he envisioned to be a Chicago-area supergroup. Invitations also went out to trombonist James Pankow, trumpeter Lee Loughnane, and singer/keyboardist Robert Lamm. Soon they were on the road touring under the name the Big Thing.

The Big Thing in L.A.

Shortly after forming, the six men

began to convene on a regular basis in

Parazaider’s basement to work out song

arrangements and collaborate on material.

As Pankow recalled on Chicago’s

website, “We figured that the only people

with horn sections that were really making

any noise were the soul acts so we

kind of became a soul band doing James

Brown and Wilson Pickett stuff.” The

Big Thing made its live debut at a club

just outside of Chicago called the GiGi-a-Go-Go in March 1967 and soon began

playing regular dates around the city and

as far away as South Dakota. Kath was

playing an off-brand Register guitar that

he purchased for $80 after a succession of

previous instruments had been stolen at

various gigs over the years.

With a wealth of talent and tight arrangements, the Big Thing drew notice from all corners almost as soon as they hit the stage. People couldn’t take their eyes off the group’s enigmatic lead guitarist, whose innovative—some might have even said “crazed”—playing style demanded attention. Pankow described Kath’s wild ways in the liner notes to Chicago Box. “We were working clubs in Chicago, and Terry was banging his guitar against amplifiers and making it talk.” Record producer Jimmy Guercio, a longtime friend of Parazaider, went to check out the Big Thing for himself at a gig in Niles, Michigan, and came away so impressed that he came calling in March of 1968. As Pankow recalled on Chicago’s website, “He told us to prepare for a move to L.A., to keep working on our original material, and he would call us when he was ready for us.” When the call came, the band was only too eager to make the move. Shortly before their departure, looking to beef up their sound, they invited local musician Peter Cetera to handle bass duties. One more change was in order, as well. Guercio didn’t care for the band’s name and took it upon himself to change it from the Big Thing to the Chicago Transit Authority, after the bus line he used to ride to school.

Upon arrival in L.A., Kath and company played almost every night at various clubs around the city, including the famed Whisky a Go Go on the Sunset Strip. In this setting, Kath rubbed shoulders with some of the biggest musicians of the day: Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Carlos Santana, and Frank Zappa, to name a few. As the band’s success grew, Kath decided it was time to trade up and jettisoned his beat-up Register in favor of a white Fender Stratocaster with a rosewood fretboard. In the previously mentioned 1971 interview, Kath remarked of the guitar, “The Stratocaster has the best vibrato, but I have trouble bending the strings without slipping off … my hands are pretty strong, I guess from playing bass all those years.” Despite those strong hands, Kath still preferred fairly light strings—but with a twist. For his high E, he typically used the high A string from a set of tenor guitar strings. For the rest, he used a stock Fender set, using its high E as his B string and then progressing on through the pack from thinnest to thickest. The inclusion of the tenor string meant there was always an extra, so the Fender pack’s 5th string was actually Kath’s low E, and he ended up tossing aside the 6th string.

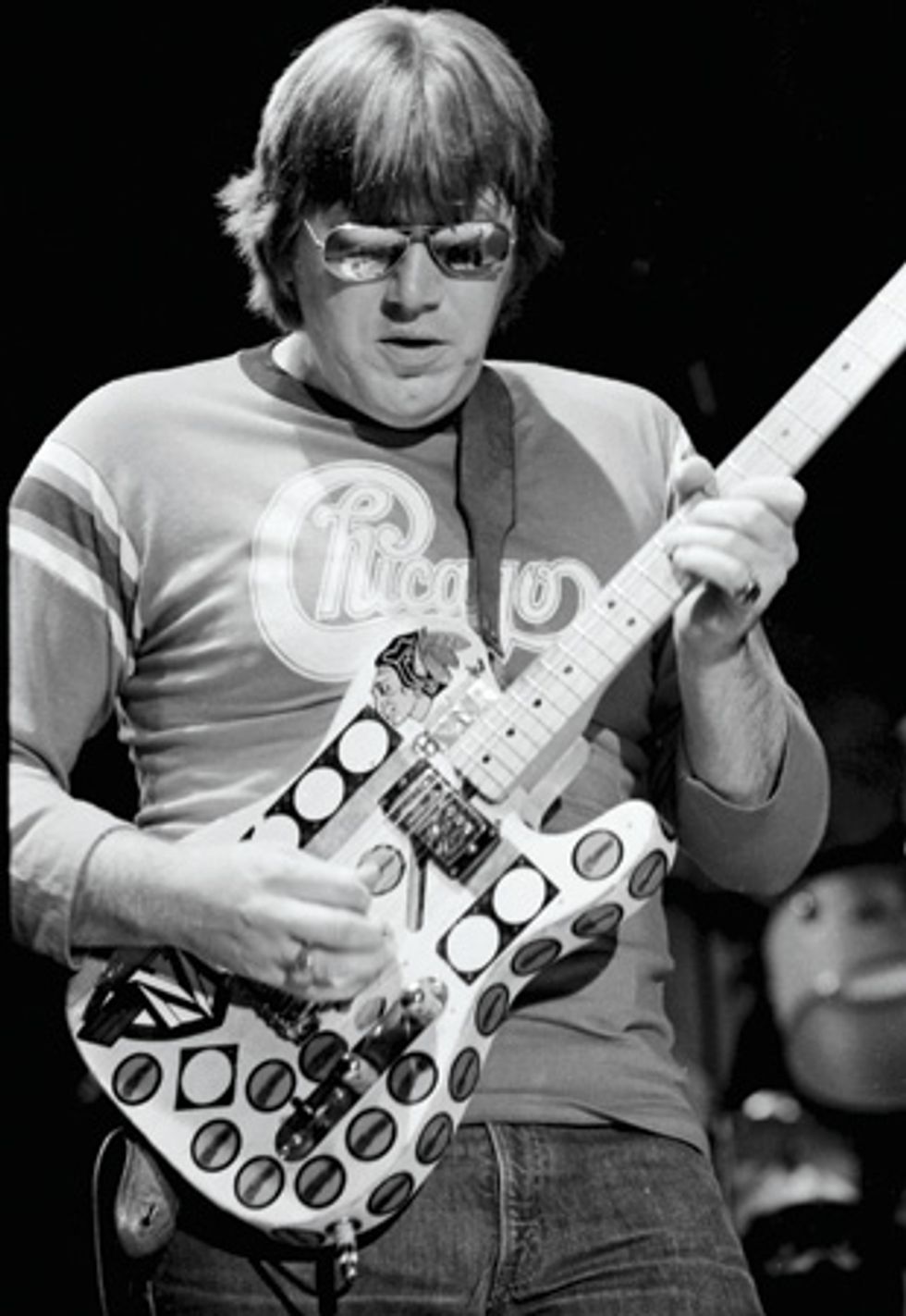

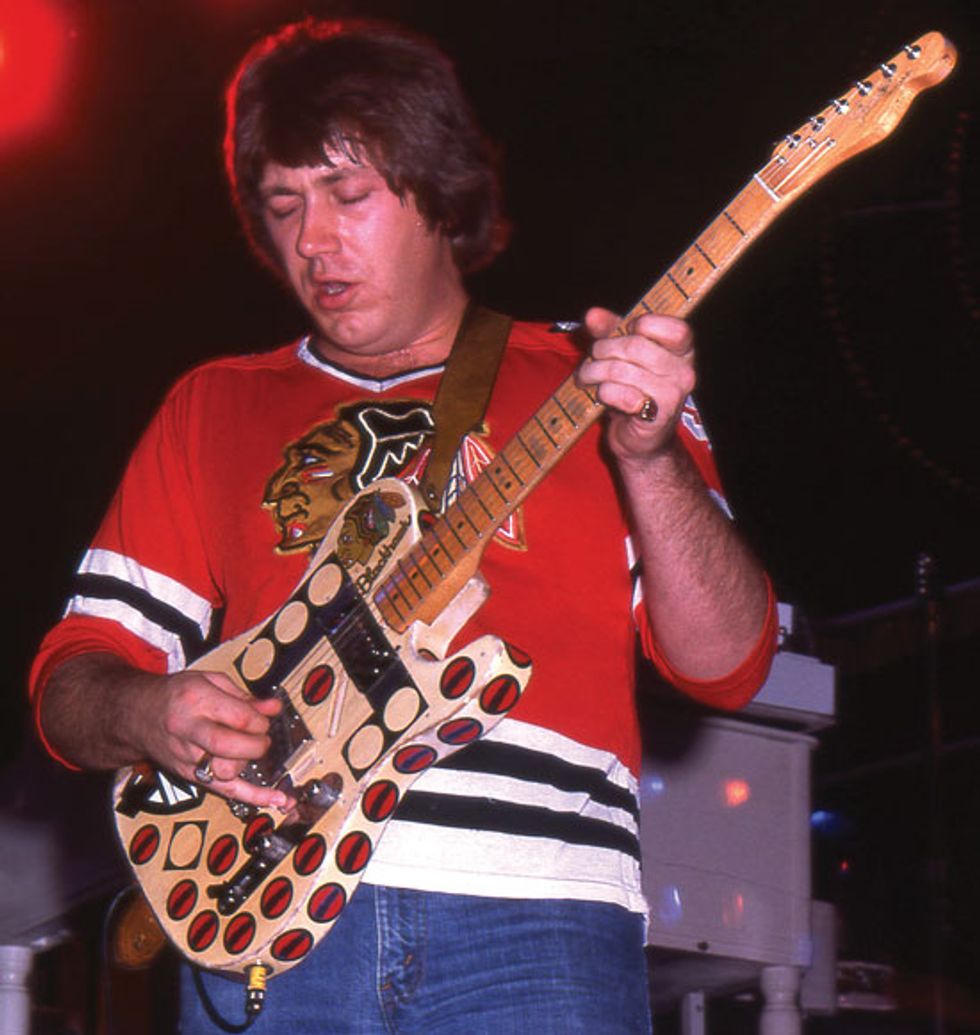

Terry Kath playing his custom Tele with Chicago in the summer of 1975.

Photo by Frank White

Though Terry Kath was about as versatile as they come, his style was mainly rooted in the jazz he was weaned on. Trying to stand out in a 7- or 8-piece band is certainly a tall order for any guitarist, but Kath was able to consistently create unique and ferocious parts that always managed to attract notice amidst a complex and varied arrangement. One of the key examples of this is the horn-heavy “25 or 6 to 4,” on which Kath’s absolutely locked-in rhythm parts are both interesting and varied without distracting from the song’s main riff. When it comes time for Kath to own the spotlight, he lets loose with a solo that pulls out all the stops, wailing on the wah pedal with all the mastery of his personal hero, Jimi Hendrix.

In fact, Hendrix was the inspiration for two other Kath standouts—“Free Form Guitar,” off Chicago Transit Authority, as well as “Oh, Thank You Great Spirit” from Chicago VIII. The former was an homage to the guitarist’s playing on Are You Experienced, and the latter was a stunning tribute to his dear, departed friend. In both cases, Kath evokes Hendrix without seeming like just another clone. “Free Form Guitar” is almost startling in its manic nature, with dive-bombs that seem to reach the lowest levels of sanity or hell … or maybe both. On the flip side, “Oh, Thank You Great Spirit” finds Kath using wah to create a soundscape that’s simply breathtaking in its serenity. From there, he layers guitar track upon guitar track to create a complex piece with intricate rhythms, searing leads, and soft acoustics.

As Chicago Transit Authority drew bigger and bigger crowds, Guercio was able to land them a coveted recording contract with CBS Records. So it was that Kath and his bandmates set off to New York City to record their debut album. In preparation for the sessions, he bought a Gibson SG that is featured prominently throughout the album. He also acquired a 60-watt Knight amplifier, as well as a Fender Dual Showman that he used extensively over the next few years both live and in the studio. The group’s self-titled double album quickly became a smash hit, selling well over a million copies less than a year after its release in April 1969.

—Chicago saxophonist Walter Parazaider

One of the most stirring tracks from Chicago Transit Authority was titled “Free Form Guitar” and featured Kath alone playing essentially experimental music reminiscent of Hendrix’s performance of “The Star Spangled Banner” at Woodstock just a few months later. The piece was recorded in one take, without the use of any pedals, and was improvised on the spot. Kath also penned the song “Introduction,” which was fittingly placed as the first track on the album and featured the guitarist taking over lead-vocal duties. It seems everyone in the band was given a moment to shine on the track, and when Kath’s turn comes he lets loose with a breathtakingly understated yet forceful solo.

What’s in a Name?

After the band’s recorded debut,

Chicago Transit Authority was forced

by the threat of legal action to change

their name once again. Kath and his

cohorts opted to just cut it short, and

thus Chicago was born. Riding high

on the LP’s success, they hit the road

for a relentless touring schedule of

200 to 300 shows a year, a pace that

didn’t abate for Kath’s entire tenure in

the group. With his newfound success,

Kath began acquiring more guitars,

including a 1969 Gibson Les Paul

Professional with a pair of unconventional

low-impedance pickups that

required a special impedance-matching

transformer for use with a standard

high-impedance-input amplifier. This

guitar became one of his favorite standbys

in the years to come.

A year after recording their first album, Chicago hit the studio to record Chicago—aka Chicago II—which was a monster success and reached No. 4 on the U.S. charts. The biggest hit off the album, the previously mentioned “25 or 6 to 4,” was written by keyboardist Lamm and is easily one the group’s most recognized pieces. After the sophomore release, Chicago went on a tear nearly unprecedented in the history of commercial music, releasing eight studio albums and one live recording over the subsequent eight years—all of which achieved platinum status. Other opportunities followed, and in late 1972 Kath and Chicago’s manager, Guercio, were approached by amplifier maker Richard Edlund to see if they’d be interested in financing his start-up company. The two men were intrigued by Edlund and his little amplifiers, and thus started Pignose Industries, which debuted their first “legendary” Pignose amplifier at the 1973 NAMM show. Kath naturally became Pignose’s first endorsee and appeared in an ad for the company, decked out in gangster attire with the slogan, “What Pignose offers, you can’t refuse,” appearing below his picture.

Kath made another guitar change that same year, finally settling on a Fender Telecaster that he used almost exclusively for the rest of his career. He asked his tech, Hank Steiger, to make a few modifications, including replacing the stock neck pickup with a Gibson humbucker and changing the bridge from a 3-saddle model to a 6-saddle version that would facilitate more precise intonation. In not-so-subtle support of his side business venture, Kath affixed a few Pignose stickers—25, to be exact—as well as a Chicago Blackhawks logo and a large sticker with the Maico motorcycle company’s logo.

A Tragic End

Despite Chicago’s enormous success

throughout the 1970s, Kath was quite

depressed. “He was an unhappy individual,”

Pankow remembered in the liner notes

of Chicago Box. “His relationship was not

going well. He was also certainly more

dependent on chemicals than he should

have been. He wasn’t addicted to anything,

but he was abusing drugs. We were all

doing drugs at that stage of the game. But if you’re incredibly unhappy and depressed

and doing the drugs on top of that, it compounds

the situation.”

On the night of January 23, 1978, in a tragic turn, Kath accidentally shot himself in the head while messing around with one of his handguns. The only witness to the incident was Chicago’s keyboard tech, Don Johnson, whose account of what happened was later summarized by Pankow. “Evidently, he had gone to the shooting range, and he came back to Donny’s apartment, and he was sitting at the kitchen table cleaning his guns. Donny remarked, ‘Hey, man, you’re really tired. Why don’t you just put the guns down and go to bed.’ Terry said, ‘Don’t worry about it,’ and he showed Donny the gun. He said, ‘Look, the clip’s not even in it,’ and he had the clip in one hand and the gun in the other. But evidently there was a bullet still in the chamber. He had taken the clip out of the gun, and the clip was empty. A gun can’t be fired without the clip in it. He put the clip back in, and he was waving the gun around his head. He said, ‘What do you think I’m gonna do? Blow my brains out?’ And just the pressure when he was waving the gun around the side of his head, the pressure of his finger on the trigger, released that round in the chamber. It went into the side of his head. He died instantly.”

The loss of Terry Alan Kath was felt across the world of music, but nowhere more than with his bandmates in Chicago. “Right about there was probably what I felt was the end of the group,” says Peter Cetera on Chicago’s website. “I think we were a bit scared about going our separate ways, and we decided to give it a go again.” The band decided to soldier on and auditioned somewhere around 50 guitarists to take Kath’s place before ultimately settling on Donnie Dacus. But without Kath’s guitar, the band was not the same. Many divide the long history of Chicago into pre-Kath and post-Kath, and it could be argued that the majority favor the earlier period.

Kath was an incredibly versatile guitarist. On one track he could play some of the wildest, most sonically expansive guitar you’ve ever heard, and on the next he could play the smoothest runs this side of Charlie Christian. He lives on in the music he created and continues to inspire those who listen to his records.

Like many new Kath fans, his daughter, Michelle Kath Sinclair—who was only 3 when he passed away—is on her own odyssey to find out more about her father. Her story is told in the yet-to-be-released documentary Searching for Terry: Discovering a Guitar Legend, and she lays out her reasons for creating the film in a message on the official Terry Kath website (terrykath.com). “I always felt that he never got the credit he deserved for his contribution to guitar. His approach to playing and writing music were unique to his own. I was always saddened by his untimely death, not only because I missed out on knowing him, but also because there was so much more that he had to offer the music world.”

Chicago’s keyboardist and lead vocalist Robert Lamm probably said it best in the liner notes for Chicago Box when he stated, “He was an original thinker. He was an inventor, in many ways. He invented the way he played his guitar. He was the kind of guy that could probably teach himself to play almost any instrument.” He added, “I don’t think there’s ever been a better rhythm player. And then, Terry’s leads are, for that day especially, world class stuff.”

Must-Watch Moments

Over the course of the decade he toured with Chicago before his

untimely death, founding guitarist Terry Kath saw the band reach great heights, including its first Grammy and 10 chart-topping

albums. This footage shows Kath and company at their most inspired.

On this 1970 live version of

the band’s most famous tune,

Kath absolutely wails on an

orange S-style guitar. The fantastically

unhinged solo begins at 2:30.

In this rare black-and-white

footage, Kath lays the wah licks

on heavy, using his signature

guitar “vocals” to accent the

lead vocals.

Kath sings lead vocals on the

first track of Chicago Transit

Authority, which he wrote.

Kath’s slick rhythm work

throughout this bluesy mid-tempo

tune is treated with a

phase shifter.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)