In the mid 1960s, the Byrds were one of a handful of bands that defined the era. Built around tight vocal harmonies and Roger McGuinn's jangly Rickenbacker 12-string, their chart-topping music incorporated elements of folk, early rock, country, and psych. But by 1968 the original lineup had disbanded and version two—featuring multi-instrumentalist and vocalist Gram Parsons—was also ending. By mid-year, McGuinn was the only remaining original member. But he had an ace up his sleeve: In July of that year, he reunited with founding bassist Chris Hillman and they recruited guitarist Clarence White into the band.

White wasn't just another guitarist. As a session musician, he had already played on three Byrds' releases. He was also a bluegrass wunderkind. Though he was only 24 years old, by 1968 he had almost a decade's worth of recording and touring experience, and his early recordings with the Kentucky Colonels had redefined the role of bluegrass guitar.

When he joined the Byrds, White was a relative newcomer to electric guitar, but he would soon innovate a way of playing that instrument. He and his bandmate Gene Parsons (no relation to Gram) invented the StringBender (often called a B-Bender), which let him execute pedal-steel-like bends without taking his hands off the neck.

White's originality and mastery of the instrument put him in the unique position of revolutionizing not one, but two distinct styles of guitar playing. Whole schools, encompassing acoustic flatpickers such as Tony Rice to steel-inspired Tele players like Brad Paisley and Marty Stuart, trace straight back to White. And yet White, despite his stature, remained an understated team player.

“His concern was to make the artist sound good," says Gene Parsons. “He was a minimalist, just putting in what was really necessary. He used to say to me, 'What you don't play is as important as what you do play.' Some of the things he originated, you'll hear guitar players emulate today. The turnarounds, phrasing, and off-time things he used to do have inspired guitar players for the last 50 years."

White, in spite of his resume and extensive discography, was just getting started when he was killed by a drunk driver in 1973. But his legacy lives on. We spoke with his older brother Roland White (whose incredible book, The Essential Clarence White: Bluegrass Guitar Leads, explains the intricacies of his brother's bluegrass playing), Clarence's close associates Parsons and Herb Pedersen, and even some of his musical heirs, like Brad Paisley, to tell White's story.

Going to California

Clarence White was born on June 7, 1944, in Lewiston, Maine. His family was French-Canadian (their last name was originally LeBlanc) and music was an important part of their lives. His father, Eric, was a multi-instrumentalist, as were his father's siblings who lived nearby. Clarence's mother often played their massive collection of country and popular records around the house, and his older brothers and sister sang, harmonized, and played instruments. Between the radio, singing, and practicing instruments, music was ever-present.

White began playing guitar when he was 5, although his father gave him a ukulele to play until he was big enough to handle the larger instrument. By the time the family relocated to Burbank, California, in 1954, the White siblings—Roland on mandolin, Eric junior on banjo, and Clarence on guitar—had the beginnings of a band and, judging by what happened next, they were already somewhat accomplished.

Soon after moving to California, the family band—first calling themselves the Country Kids and then the Country Boys, before finally recording as the Kentucky Colonels—began winning talent contests and performing on local radio and television. They shared stages with established greats like Joe and Rose Lee Maphis, Lefty Frizzell, and many others, and eventually landed a spot performing on the nationally televised The Andy Griffith Show.

“When the show broadcast a few weeks later, we started getting calls from our cousins in Maine," recalls Roland White. “They said, 'We saw you on The Andy Griffith Show, how did you get that job?' I thought it was just a local show. We didn't know it was nationwide."

In 1959, the Country Boys started playing at the Ash Grove in Los Angeles. Their lineup at that point was Roland and Clarence on mandolin and guitar, Eric on bass, plus Billy Ray Latham on banjo, and LeRoy Mack on Dobro. The club was the local center of the then-booming folk revival. It was their first time playing through a proper PA, with onstage monitors, which was the kick Clarence needed to step up as a soloist. “It made it a heck of a lot easier," Roland says about being able to hear themselves play. The club was also their introduction to a more sophisticated, college-educated audience, and connected them to other like-minded musicians their age.

“I met Clarence in Los Angeles in about 1963," says multi-instrumentalist Herb Pedersen. “My band, the Pine Valley Boys—a bluegrass group from Berkeley—came down to play at the Troubadour, which at that time had an open mic on Monday nights. It featured artists like the Kentucky Colonels, David Crosby, and Roger McGuinn as single artists, Chris Hillman was in the Golden State Boys at the time, and that was right around the time I met Clarence. It was just astounding to meet these guys."

White recorded his first album, The New Sound of Bluegrass America, with his band, renamed the Kentucky Colonels, in 1962, when he was just 18. In addition to White, the album features Latham on banjo, Mack on Dobro, and Roger Bush on bass—Roland had been drafted, stationed in Germany, and missed those first sessions—and Merle Travis, Johnny Bond, and Ralph and Carter Stanley all had a role in its production, while Joe Maphis wrote the liner notes. Featuring cross-picking and other advanced techniques, White's lead style had evolved from his first days at the Ash Grove, and the album represented a new stream in bluegrass music with guitar as a prominent lead instrument.

An early White family band photo of the Country Boys, taken in the 1950s. The lineup included siblings JoAnne White on bass, Roland White on mandolin, Eric White on banjo, and Clarence White on guitar. Photo courtesy of White Family

“Doc Watson was one of the first lead guitar players on acoustic guitar," Pedersen says. “He played fiddle tunes on the guitar and that was pretty amazing. But Doc's style was pretty rigid: It was pretty much note-for-note, and it didn't swing all that much. He just played the fiddle tune like you'd hear it on a fiddle. But with Clarence, he would incorporate different little push beats and that kind of thing. He was a very sly guitar player. He would sneak things over on you and you had to pay attention."

After Roland's discharge from the army, the band did a number of East Coast tours, which included shows in New York, Boston, and a feature at the Newport Folk Festival, and recorded a second album, Appalachian Swing!, in 1964. White's guitars at this time were a duo of Martins: a D-18 and his iconic D-28 Herringbone (now owned by Tony Rice), although the guitars suffered their share of abuse. In addition to manhandling his instruments (He filled one guitar with sand and shot the D-28 with a BB gun.), he ran over both guitars one evening after a gig in Massachusetts, doing significant damage to the D-18. The guitars were repaired at Herb David Guitar Studio in Ann Arbor, Michigan, which White claimed improved the sound of the D-18.

White was a discerning musician, but a utilitarian gearhead. Consider the humble beginnings of his D-28. “We found that in McCabe's Guitar Shop in Santa Monica," Roland White says. “We would go to pawnshops once a month in L.A., and we went by McCabe's and there was this guitar in the corner. The fingerboard just had tape around it, but it was taped to the neck. We asked, 'What do you want for that as it is?' The guy went back and talked to his boss and I think he said either $25 or $35, so we bought the guitar. It was Clarence, my brother Eric, Billy Ray, and myself, and we scraped up money and gave it to him. We took it home and my dad said, 'I can't fix that.' So we took it to this guy in L.A., Milt Owen. He said, 'I can put the neck back on there.' But he looked it over, and the top had been sanded thin. He said, 'You'll never be able to use heavy Martin strings on there. You're going to have to use light-gauge strings, because the top will bulge. You won't be able to play it very well.' He put the guitar neck and fingerboard back on there, strung it up, and I think we paid him $15 to do it. We picked it up a week later, brought it home, and Clarence played it a bit. But he said, 'I can't play it with these strings. I'm going to put on some heavy-gauge strings.' Sure enough, the top bulged up at the bridge. The only way he could play it would be in open G or put a capo on to play the G chord like an A, and then after that it would get real sharp."

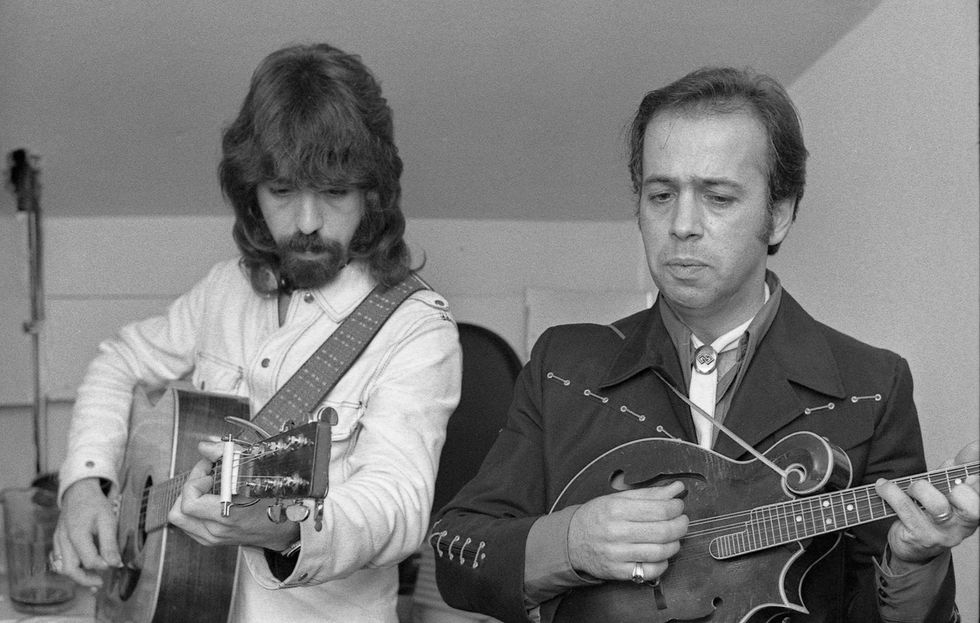

Clarence White (left) and his brother, Roland White (right), played in bands together for decades; first in the Country Boys and then the Kentucky Colonels. This photo was taken at L.A.'s Ash Grove club in 1972. Photo by Frank Chino

Electric Bends

As the '60s wore on, the folk revival took a backseat to rock 'n' roll, and the Kentucky Colonels went on hiatus. Roland moved to Tennessee and worked with Bill Monroe and then Lester Flatt, and Clarence—at the suggestion of Telecaster legend James Burton—started playing sessions. It was at that time he met his future bandmate and collaborator, multi-instrumentalist and tinkerer Gene Parsons.

“The way we met was through a guy named Darrell Cotton," Parsons says. “I was in a band with him, along with Gib Guilbeau and Wayne Moore, and he had a recording studio in Hollywood. He had booked a session, and said, 'You've got to meet this young guitar player, Clarence White—boy is he hot stuff.' I hadn't associated the name with some of the stuff I'd heard with the Kentucky Colonels, and besides, this person he was talking about was an electric guitar player. Anyway, the session went off really well, we hit it off with Clarence, and he joined our band right away—which ended up becoming Nashville West. It was so early in his electric career that he was still using a capo on the electric guitar."

White, along with Parsons, Guilbeau, and a few others, did sessions for noted producer Gary Paxton—first in Hollywood, and then near Bakersfield, playing on country-flavored tracks by such artists as the Gosdin Brothers, Jack Reeves, Bruce Oakes, and many more. That's when White, in collaboration with Parsons, modded his Telecaster with a mechanical string bender affixed to the strap. The device, which he ultimately connected to the B string, allowed him to bend the pitch up a whole-step—similar to pushing a string behind the nut, which many players do on a Tele—but without having to take his hands off the fretboard, and those bends became integral to his voice on electric.

“Clarence was the leader of that California hippie-rock bender movement," country star Brad Paisley says about White's influence at that time. “He played that bender and it became such a cool, honky-tonk, California country sound. He made the Tele sound twangy and unique."

Nashville West—White, Parsons, Guilbeau, and Moore—took their name from a club they played, and were an important part of the Southern California country scene. In addition to recording their own music, they did numerous sessions—as a group and as individuals—and it was through his session work that White met Byrds members Gene Clark and Chris Hillman, played on early demos for what was to become the Flying Burrito Brothers (with Gram Parsons), and eventually found his way into the Byrds.

“Clarence had played on records like Younger Than Yesterday and The Notorious Byrd Brothers," Parsons says about White's work with the Byrds as a session player before joining the band. “He also did Sweetheart of the Rodeo with them. They wanted to duplicate some of the steel stuff that Lloyd Green and JayDee Maness did on that record, and in particular on the tune 'You Ain't Goin' Nowhere.' Clarence was able to do that with his string bender. They also knew he would be a great addition to the band, and they hired him. The drummer was Chris Hillman's cousin, Kevin Kelley, at that point. I guess they weren't satisfied with him, although I thought he did a wonderful job, and Clarence was basically the guy that got me in. He said, 'You need to use my drummer Gene.' I did an audition and I was in."

On both acoustic and electric, White used a hybrid-picking style that combined a flatpick with his middle and ring fingers. But in his electric playing, he broke from the traditional bluegrass approach of position-style playing based on open chords.

“Electric guitar and acoustic guitar are two different animals," says Pedersen. “On electric guitar, Clarence could really branch out. He used the whole neck, could go up and down on it, and did pull-string things. But he would still use a straight pick and a two-fingers style. He incorporated that from his acoustic playing."

White was with the Byrds from 1968 through 1973, appeared on five albums as a band member, and, except for Roger McGuinn, had a longer tenure in the band than anyone else. His only electric guitar throughout this period was his StringBender-equipped Telecaster, although his amplifiers varied. In the studio, he usually used a Fender Vibrolux, but onstage—depending on the size of the venue—he used different amps including a modded Dual Showman, a modded Twin, and a Super Reverb. He also used a Leslie cabinet miked in stereo.

“It had a blanket over the top of it, a mic on one side, and another mic 180 degrees on the other side," Parsons says. “It was panned far right and left, so you'd get the chorus effect in the house. It had two speeds—the fast vibrato and the chorus, which was a slow revolution. He mostly used the slow chorus."

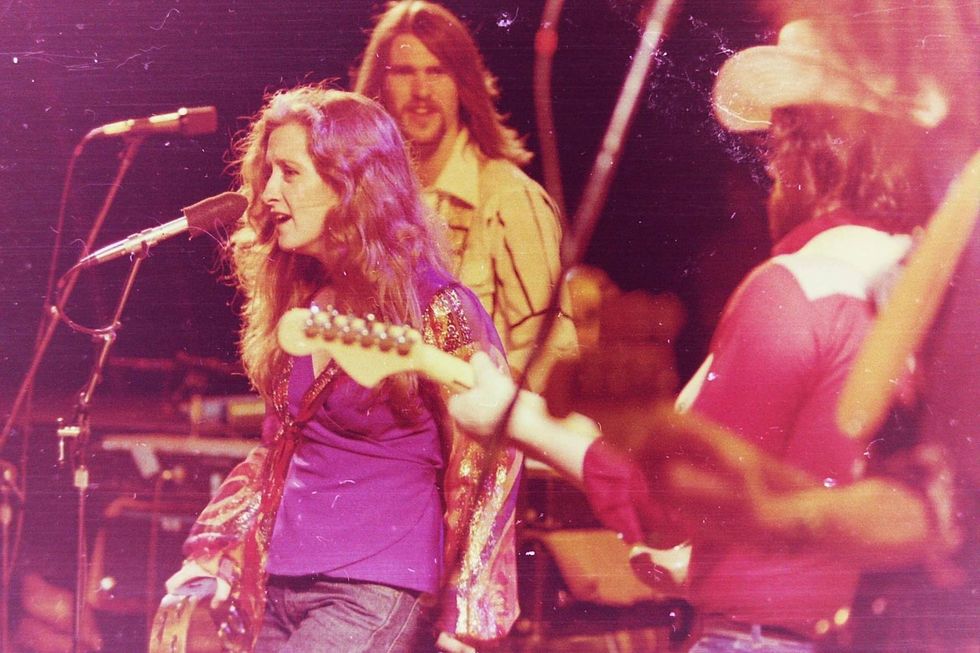

The Byrds circa 1970, from left to right: Roger McGuinn, Skip Battin, Clarence White, and Gene Parsons. Photo by Joost Evers

White's tenure with the Byrds was during a time when the band was transitioning from having to be very loud onstage to relying on the PA. The band's soundman was the legendary engineer Stuart “Dinky" Dawson, who set them up with a WEM PA system, which was one of the earliest modern PAs. That meant, at least in theory, that the stage amps could be a lot quieter. “But I don't think the guitar players ever got over having big amps onstage," Parson says. “It was loud."

White didn't use many effects, although he did have an out-of-phase switch for when both pickups were activated on his Tele. He also had a custom distortion unit, built for him by pedal-steel guitarist and amp tech Orville “Red" Rhodes. Despite the many different—what today would be vintage—tube amps he used, he relied on the pedal for fuzz A good example is “Lover of the Bayou" off the 1970 release Untitled. According to Parsons, that pedal was stolen at a show, and they had trouble finding another that sounded similar.

White used his acoustic guitar with the band as well, and although he took a laid-back approach with the engineers, he had an intuitive sense when it came to miking his instrument.

“Having done so many acoustic shows with an acoustic guitar, he knew the sweet spot," Parsons says. “He would gravitate to that spot and hold the guitar so it was in the position in relation to the mic that sounded the best."

Through his work with the Byrds, as well as his continuing session work, acoustic shows, and reunions with Roland, White's reputation and influence began making a mark. Aspiring guitarists came to shows to stand in the front row and gawk, and established players stopped by to check him out, and to meet him.

“We were playing at the Whiskey a Go Go, and a finely dressed man in a mohair suit, with a feather in his cap, came to the dressing room door," Parsons remembers. “The road manager said, 'There's a gentleman here to see you Clarence.' The guy walked in and said, 'I am an admirer of yours. I used to come down to the Ash Grove and hear the Kentucky Colonels play. I really love the way you play guitar.' Clarence said, 'Well thank you very much, and what was your name?' And he said 'Jimi Hendrix.' Clarence said, 'I'll be darned. I like the way you play, too. You're the whoo-whoo guy,'" Parsons says, chuckling at Clarence's description of Hendrix's wah-wah work.

Post-Byrds

White left the Byrds in 1973, and he was busy. He played in the bluegrass supergroup Muleskinner—with David Grisman, Peter Rowan, Richard Greene, Bill Keith, John Kahn, and John Guerin, played on many sessions, and toured Europe with the New Kentucky Colonels, which featured his brothers Roland and Eric, plus either Pedersen or Alan Munde on banjo. He signed a deal with Warner Brothers, began work on a solo album, and did a short East Coast tour with an all-star lineup that included Gram Parsons, Emmylou Harris, Gene Parsons, the Country Gazette, Sneaky Pete Kleinow, and others.

But early on July 15, 1973, White was playing a gig in Palmdale, California, with Roland, when tragedy struck. He was loading his gear into his car after the show when a drunk driver hit him head on. He died at the scene, just over a month after turning 29.

“When I got fired from the Byrds, I went to Warner Brothers, got a contract, and came out with a solo album, which of course, Clarence was on," Gene Parsons says. “Clarence, Emmylou Harris, Gram, and the Country Gazette—which Clarence was playing on—also went with Warner Brothers. We all had the same manager, and we were going to do a European tour promoting all of our albums coming out at close to the same time, so we did a pilot tour back East to just cement how we were going to present ourselves in Europe. But not long after that, Clarence got killed by a drunk driver, and, soon after, Gram did himself in, in the Mojave Desert, right where I was raised. In fact, my dad called and said, 'I am so glad to hear your voice son. They got your picture on the front page of the local paper saying that you killed yourself out here in the desert'—because my name is Parsons, too. So that took the wind out of the tour to Europe idea, and we all moped along. I didn't play any music after that for a while, because it just broke my heart. I tried to fulfill what Warner wanted me to do to promote my record, but I'm afraid I let them down. I asked them to drop me, which they did."

White had started young, was an in-demand player, and despite his early death left behind an extensive discography. His influence was massive and not only helped change the role of the acoustic guitar in bluegrass, but because of his work with the StringBender, defined the sound of modern country guitar. And a big part of that may have been due to how easy he was to work with.

“It was always good working with him," Pedersen says. “He was a solid guy. He was a band guy. He never—for lack of a better term—took his solos and tried to stick them up your ass, and he had a wonderful way, a subtle way, of playing."

“Clarence never played anything the same way twice," Parsons says. “When we'd do 'Eight Miles High,' which we did every night on the road, every night was different. There were some parallels and some similarities, but it was always a different trip. His timing and his drive were just impeccable. Man, he'd come out of the chute burning—he would do these odd-timing things—I think he would get out of his comfort zone, go out into the cosmos, and we'd wonder if he was going to get back in time. He always did, but it was like a story he was telling that was different every night."

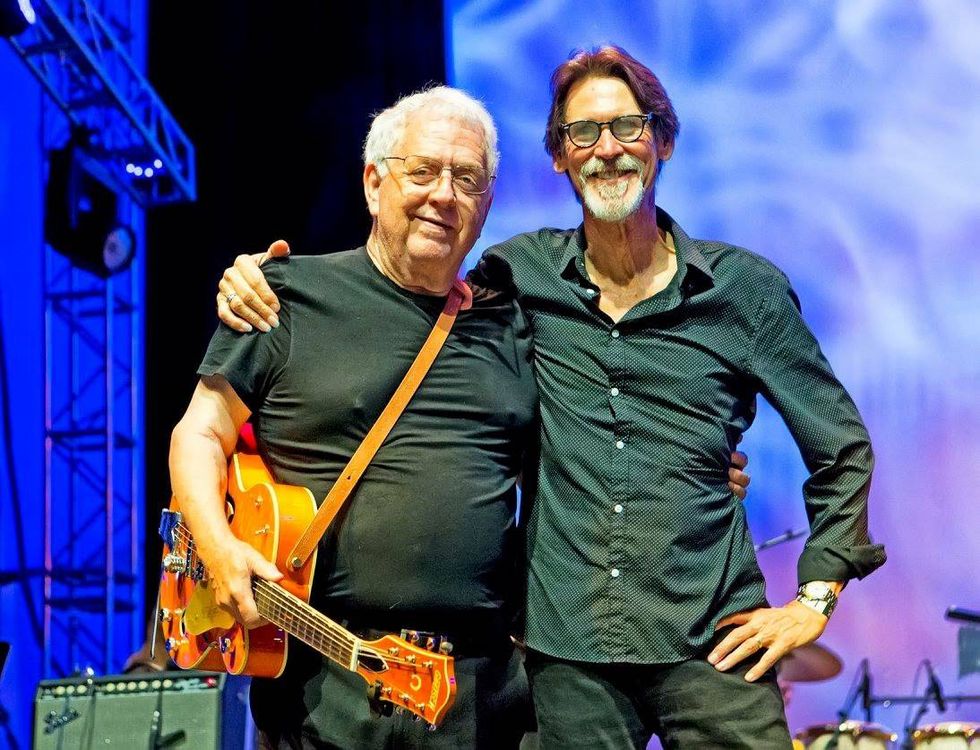

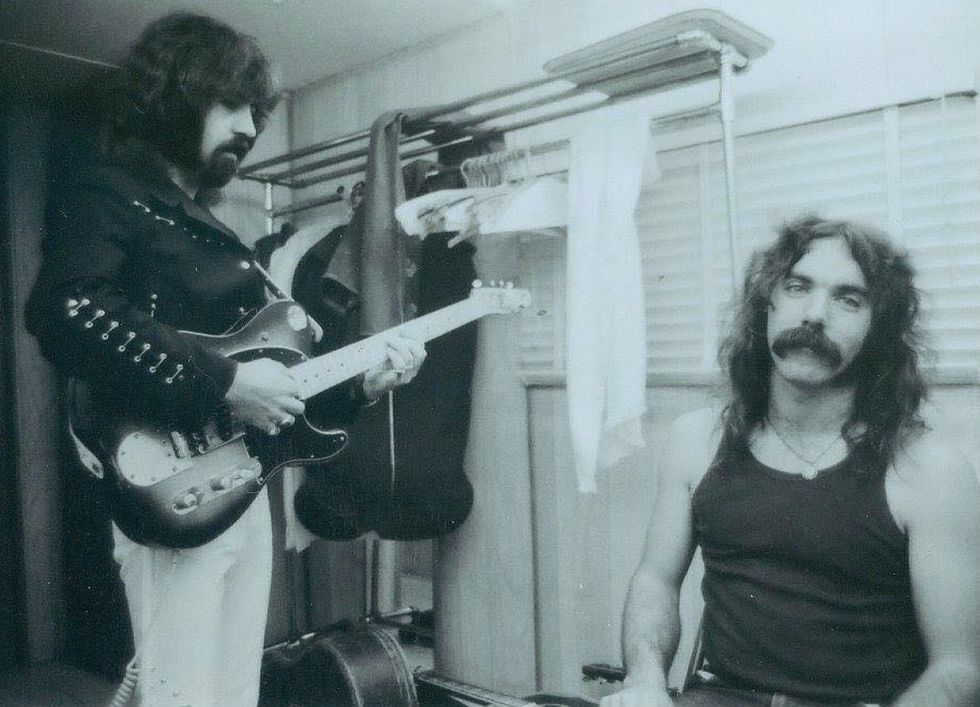

Longtime friends Clarence White (left) and Gene Parsons (right) played in the Byrds and Nashville West together. Parsons built the first version of the StringBender for White's Telecaster and installed it in 1968. Photo courtesy of Gene Parsons

Gene Parsons on Building Clarence White's StringBender

Two instruments associated with Clarence White took on a life of their own after his passing. One was his battered Martin D-28 Herringbone, now owned—and often played—by Tony Rice. The other was his 1954 two-tone sunburst Telecaster that he and Gene Parsons modded with the first StringBender—ultimately attached to the B string. The instrument was White's only electric guitar, and he used it throughout his career. Today it's owned by country legend Marty Stuart.“I've picked up Marty's somewhere along the way," Brad Paisley says about his encounter with the instrument. “It's heavy. It's a double-bodied guitar—that was before they had it all figured out—it's like two Teles for the price of one."

Below, Gene Parsons tells us the history behind the StringBender, some of the challenges they faced developing it, the reason White preferred an extra-thick instrument, and White's ease in learning to manipulate the device.

What was Clarence's reaction when you first cut up his guitar?

I'll tell you the story. We were doing a session and we got the basic track down. Clarence used to chime a string and pull it over the nut—a lot of people do that now on a Telecaster, raise it up a full tone—and he said, “Gee, I wish I had a third hand. I want to do this in the second and third position." I said, “I'll be your third hand. You get the position and I'll pull the string over the nut." We were fooling around there. We didn't use it because it was pretty crude, but we heard that sound. Clarence said, “You're a mechanic and a machinist—figure out a way to do that." I said, “No problem. We'll put a steel-guitar mechanism on there, some cables, and foot pedals on the floor." He said, “No, I want it to go in the guitar case. I don't want any stuff that I have to hook up to it. I want my hands to remain in their normal stance."

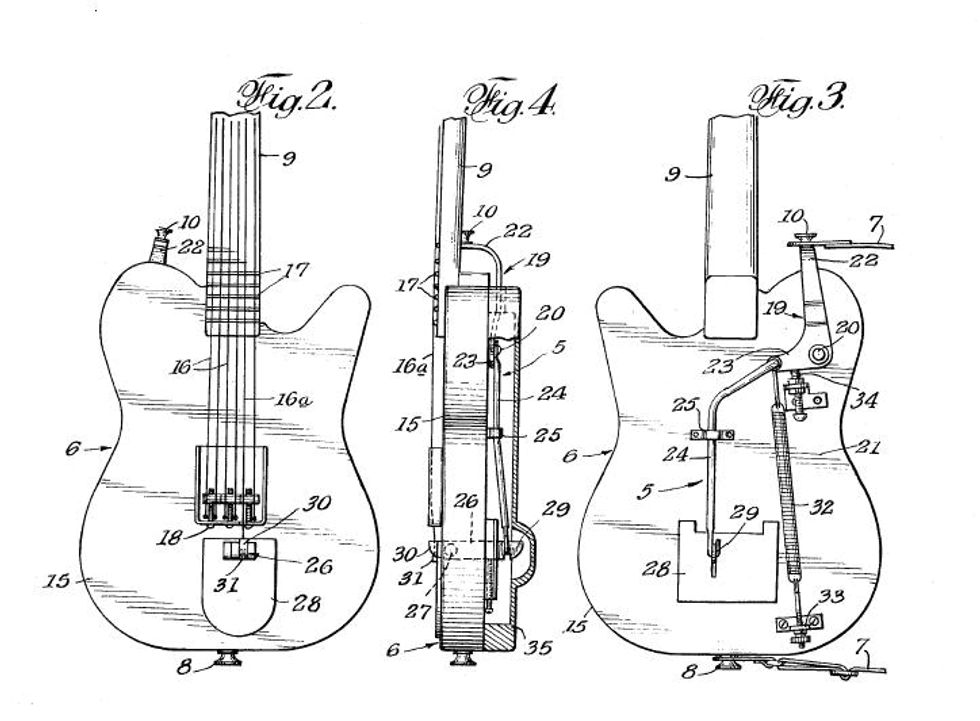

Original schematics from the official 1968 patent for the StringBender developed by Gene Parsons and Clarence White.

I thought about it for a while. There was a guy down in San Diego who did volume swells with the strap. He had a lever hooked up to a volume control, and it was spring-loaded. All he had to do was push down on the neck and he could make the volume swell, rather than use his little finger on the control knob. I thought, “Ah ha! That's what I'll do. I'll hook it up to the shoulder strap." I got some parts from Sneaky Pete [pedal-steel guitarist Peter Kleinow] and drew up some drawings. I showed them to Clarence, and he found another guitar to play. He handed me the guitar, and the first thing I had to do was cut about a 1 1/4" square out, clear through the guitar, behind the bridge. I did that, and the next morning I went over to Clarence's house, sat down at the breakfast table, and slid this piece—that 1 1/4" sunburst piece—across the table. He looked at it and said, “Oh God." I said, “We're past the point of no return now." But as it turned out, it was a successful operation. The patient survived. And Clarence invented a way to play that changed music.

Did it take him a while to get used to it?

No. He started doing it right away. I documented his playing before he had a string bender—it's on the record on Sierra Records, Nashville West—because I wanted to have that to refer to after I installed the string bender. Clarence was using the string bender almost too much when he was on his learning curve. He got all the licks together quickly. He was incorporating them and not using his other licks—which he had such a big repertoire of—and was relying on the string bender. I brought the tape of him playing without a string bender and played it for him. He went, “Okay, note to self, I got it." After that, he used all his old licks, and incorporated the string bender with them. He had his wonderful and unique style, and it developed rapidly.

Clarence White's original StringBender-equipped Telecaster, which is now owned by Marty Stuart. Note the metal plate, indicated by arrow, covering the slot where the 1 1/4" of sunburst body was removed to accommodate the bender. Photo by Frank Chino

Did he make suggestions or tweaks, or did you improve it during those first few years?

No. At first, we didn't know whether we were going to pull the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, or 4th string. We figured it would probably be the 2nd string, because you can easily bend the 3rd string, and the 1st doesn't lend itself to as many combinations. But I put four pullers on there, just so we had some flexibility. We experimented with the first string for a while, with a little button under the elbow, under the forearm—but we discarded that. The design changed quickly because it was a heavy device. The steel guitar mechanism stuck out the back of the guitar, and I needed to put a cover over it. Clarence said, “I never got used to the thin body of a Telecaster. I'm so used to the D-18 I've been playing since I was a little kid. Why don't you put an extra body—like three-quarters width of a body—which is the same shape as the guitar body on the back, so that it would be about the same width as a D-18." That's what I did. Not everybody wanted that, of course. I didn't do any more string benders for a while. But then I had people approaching me, wanting to do it, and I came up with the current design—or at least the forerunner of the current design—which is the quieter, much more reliable, lighter design that we use today.

Does the strap only move if you actually push it? Will it activate if you're jumping around onstage?

Different people have different approaches. It's spring-loaded and it's adjustable. You can adjust the tension on it. If you don't want it to activate by itself if you're jumping around onstage, you go with a tighter spring tension. One of the times that I saw Marty Stuart, I was messing with the guitar, and it had almost no spring tension on it at all. I said, “Marty, we need to tighten up or replace this spring." He said, “Don't do that. I like the neck to just drop. I hold the neck up." It's all in what you get used to. But it can be adjusted so it takes some effort to activate it so that if you're doing calisthenics onstage, it doesn't activate by itself.

Clarence White Essential Listening

Right off the bat, Clarence White's playing is an education in the tasteful use of the StringBender. As an added bonus, the video is also illustrative of eclectic '60s dancing styles.White's ensemble playing and lead work are fantastic. This is also a great example of his vocal prowess, and his solo, at the 3:35 mark, is a demonstration of his masterful off-time playing. And yes, polyester rules.

This intimate gig from 1973 offers incredible closeups of White's acoustic playing and hands. Roland White's mandolin playing is equally impressive.

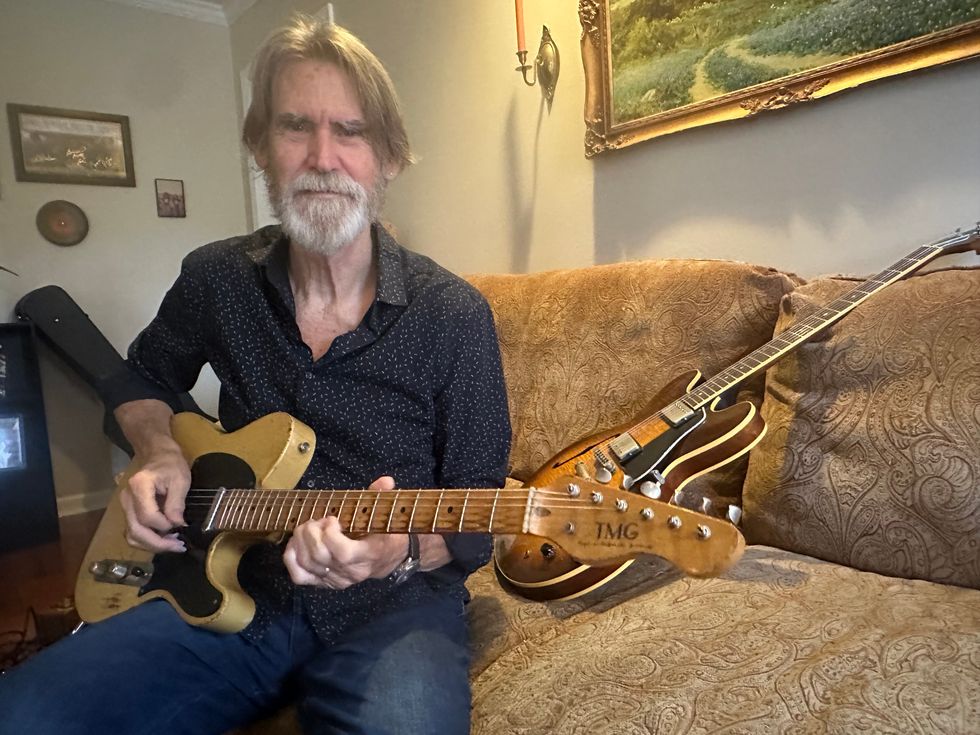

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski