Last year, after four decades of touring and recording, prog-rock giants Rush came to a halt following Neil Peart’s retirement from drumming. While the trio remain close friends, and bassist and frontman Geddy Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson haven’t ruled out the prospect of further collaboration, each of Rush’s members are currently living life as a solo act.

Lee is a voracious collector of everything from wines to baseball ephemera, and over the past decade has increasingly turned that interest toward vintage bass guitars. The virtuoso says he initially set out with the modest intention of chasing down nice examples of the instruments wielded by his musical heroes: a ’62 Fender Jazz bass like John Paul Jones used in Led Zeppelin, a Gibson EB-3 like Jack Bruce’s in Cream, and so on. However, Lee is afflicted with the curse of the completest, and his curiosity grew with the purchase of each old instrument. Questions about the evolution of particular models and the spaces they occupied in the relatively short history of the electric bass led Lee deeper down the rabbit hole.

Eventually, Lee, who had previously only purchased basses as tools to create music, amassed a collection of over 250 vintage examples. Next came the idea to document his incredible collection and passion for the instrument in a book. Thus, Geddy Lee’s Big Beautiful Book of Bass was published in December 2018.The volume features world-class photos and notes about the basses in Lee’s collection, interviews with some of the celebrated players that shaped his musical world—including John Paul Jones and the Rolling Stones’ Bill Wyman, and showcases Lee’s transition from collector to archeologist of the bass.

Premier Guitar spoke with Lee over the phone as he relaxed at home in Toronto with his beloved Norwich Terriers. The conversation covered Lee’s passion for collecting and his new book, some of the rare instruments he’s now the custodian of, the challenges of Rush’s music, and what the future may hold for him as a player.

The collection of basses you’ve put together is pretty astounding.

It was no small task, and it was sort of a crash course for me. Considering that I’ve been playing for over 42 years, I probably should’ve known half of this stuff, but collecting vintage wasn’t really my thing. The whole vintage thing came to me over the last, maybe, 10 years. Prior to that, I was only looking at my instruments as tools to get me the sounds and playability that I needed to have onstage and in the studio.

When I was a kid, I collected stamps, and then when I got turned on to music, I had a big vinyl collection and I was pretty fanatical about that. Over the years, I got into first edition books, baseball stuff, and then there’s the wine“issue,” but the bass collecting and this book really felt like the first time that I was paying something back to the instrument that’s given me my entire life. It was a project that not only edified me in terms of what the world of instruments was like between 1950 and 1980, but it also was kind of a full circle for me as the first good instrument I ever bought was a 1968 Fender.

Was there a particular bass that catalyzed your transition from player to collector?

Yeah. The first instrument I bought as a collector was a ’53 Fender P bass, and I wanted that because it’s my birth year. Collectors seem to look for stuff from their birth year as a kind of ego thing. I guess everyone wants to celebrate their own entry into the world, right? So that’s where it started for me and that was a very important piece because, in researching that piece, I learned how early 1953 really was for the electric bass, having only been invented as a commercially available thing in ’51. That bass really got me thinking about that period, and, as a collector, it’s access to a window into history that really gets me motivated. Through that, I started learning about Leo [Fender] and I started being very interested in the changes that happened in the first 10 years of the P bass, because from ’51 to ’61 that instrument went through a lot of changes as Leo tweaked and looked for the ideal version of the Precision bass. Those early iterations and the modifications he made are interesting not only in learning about that instrument, but also learning about what made Leo Fender tick. Suffice to say Leo’s a fairly interesting character in the history of vintage instruments. That was one aspect that really got me turned on, and then I started casting my gaze to other instruments.

TIDBIT: For Geddy Lee’s Big Beautiful Bass Book, he interviewed bassists like Bill Wyman and John Paul Jones who could talk with authority about buying basses during certain periods.

Ever since I started using my ’72 Fender Jazz bass as my main stage instrument in the early ’90s, I’ve been obsessed with finding a backup for it that matched it tonally. I had a really hard time finding one that sounded the same, and have always wondered why certain instruments have a particular tone and why it’s so difficult to find others that sound the same. That lead me on my Jazz bass hunt, and I had heard so many things about the pre-CBS era of Fender, I really wanted to understand what had happened from 1960 and 1972 to make my main Jazz bass what it is, and how many changes had that model gone through during those years. Was it the same thing the P bass had gone through in its first 10 years, with these really dramatic changes to the design? And it was those questions that really led me down the rabbit hole.

I love how wholly you’ve thrown yourself into the archeology of bass—especially when it comes to mavericks like Leo Fender.

These are products of humans, right? So when a bass hits my hands, I want to know the context. Who made it? Why did they make it? Where did it come from? Where did the idea for it come from? What stage of development in the guitarmaker’s mind was this instrument? Does it represent the ultimate product for him, or was it something that he made along the way to getting there? Those are burning questions for me, and they happen no matter what kind of man-made object I turn my gaze on … whether it’s wine or watches or whatever! All of these things are just entry points, but it’s about learning more about the world and celebrating the incredible achievements of human beings!

Was the book something you had in mind as you got deeper into collecting, or just a by-product of it?

The book was a by-product, and I didn’t intend to collect so many basses when I started. I originally set out to collect maybe a dozen basses that represented the models played by the guys that taught me everything through my listenings—my heroes. So I was after a Gibson EB-3 that represented Jack Bruce, a Hofner 500-1 Violin Bass that represented Paul McCartney, a ’62 Fender Jazz bass like John Paul Jones used on the early Led Zeppelin records. Those were what I set out to put together in a modest collection just to be able to have some fun with them, but when I get into collecting, I turn into sort of a completist. I get a few of these things and then get curious and have to answer the questions, like what was different on the model from the year before, and then the year after, and so it goes.

What I discovered over the course of building this collection is that there are stories connected to these instruments, and bits of minutia that maybe everyone doesn’t know. And there are people that I came into contact with through collecting that were fascinating to talk to and had rich stories to share. Those were the reasons I finally thought maybe I should put these things down in some sort of compendium so the stories are preserved and the joy of collecting is shared with other like-minded people.

When Lee began collecting basses, he set out to acquire about a dozen examples of those instruments preferred by his idols, with this Hofner 500-1, for example, representing Beatles-era Paul McCartney. Photo by Richard Sibbald

There are some pitfalls to avoid in collecting vintage guitars and basses. Especially now, as people have gotten really good at mimicking the details of old parts and replicating the way vintage finishes age—even studied under blacklight. How did you go about educating yourself as a buyer? Did you get burned along the way?

Yeah. I don’t think you’re an honest collector if you don’t experience a couple of burns in your excitement! In the old days, when you became a collector of anything, you had to travel to the guitar shows and the fairs, or stumble upon guys that were trying to sell their instruments in newspaper ads and such, and you really had to know at least a little bit of what you were talking about because you had to experience them in person. Now we live in a world that’s opened up in its entirety to sellers with the internet, so how do you know an instrument in Malaysia or somewhere is the real deal? A ton of communication has to ensue, a ton of photographic evidence has to be exchanged, but at the end of the day you have to have enough knowledge—or at least access to enough knowledge—to verify that what you’re after is the real thing.

So yeah, I’ve bought a couple of instruments that didn’t pass muster once we opened them up and got them under the blacklight, and I’ve bought some that fooled a lot of experts along the way.

Does an instrument’s story ever outweigh how original it is, when it comes to your enjoyment of it as a collector?

I have a 1963 Strat that required an unbelievable amount of detective work and is an example of something like that. It has a matching headstock, which is very rare, and the factory numbers and etchings under the pickguard are all there, but it turned out not to be so straightforward and the guitar is a whole story unto itself. That is really fun to discern for me, and the seriousness of that all comes down to what the sale price is at the end and if you’re buying something that someone is trying to deceive you into thinking is all original when in reality it’s original-ish. That said, another thing I avoided in the book is talking about the cost or value of these things. I really try to seperate that side from the simple celebration of these instruments.

The allure is learning, and there is so much to learn in this and the other things I get into collecting. This obsession with things that represent the ingenuity of man is endless and endlessly edifying.

I know you’ve also got some pretty remarkable guitars, including a ’59 Les Paul Standard.

I do! When Joe Bonamassa was in town a few weeks ago, he came over for dinner and we had a gathering of the Toronto guitar geeks at my house and had a great time. Joe brought it to his soundcheck the next day and gave it his thumbs up! I like guitars, too, but I don’t play them. I can play guitar and I use it from time to time as a writing tool, but I’m a bass player and sometimes I feel like having these amazing guitars is a bit of a waste in my hands, and they should be with players like Joe. But I do have a mad passion for certain guitars. I always said Alex, my partner in crime for all these years, sounds best with a 335 or a Les Paul in his hands. His white 355 is such a killer, great-sounding instrument!

Is there anything you’re still hunting?

A real pre-CBS surf green Fender Jazz or P bass. I’m still looking for a ’68 Fender Telecaster bass in the blue floral print. It’s remarkable how hard those are to find. The paisleys are out there and I have a couple of those, and I even have the blue floral Tele guitar, but I haven’t found the bass yet. I’m looking for a super early Rickenbacker 4001 from the early ’60s. I have three Ric 4000s from the early ’60s, and I have a ’64 4001, but I’m really looking for one of the first ones.

The interviews in the book are great and include some your heroes, like John Paul Jones. What was it like putting that part of the book together?

It was very difficult to have so few interviews. I could’ve easily talked to 30 guys, but there’s only so many pages and there’s only so much time. I really wanted to talk to players that represented the period I’m specifically talking about in the book, like Bill Wyman and John Paul Jones. These are guys that can talk about actually buying basses during that period.

John Paul is such a fantastic character and wonderful storyteller and generous man. We spoke about his early days and what he loved about the bass, and especially his ’62. And Bill Wyman in many respects invented the electric fretless bass by making it himself, and he’s a character that’s played so many different instruments—so he could speak to the reality of so many different instruments. I wanted to speak with people that connected with the book on a level beyond just being great players. It was really about the combination of being a profound player and having that collector’s mindset, or having the experience of having been a witness to the golden age and being able to describe it.

Among the rare basses in his armada are several Fender Telecaster models. He has a few paisley-finish examples but is still on the hunt for one in a blue floral print. Photo by Richard Sibbald

Jeff Tweedy is a collector that I really appreciate, as he just buys things he loves or finds weird, and he’s got just a marvelous collection. I had a really great time interviewing him for the book and spending some time with him and his gang at the Loft in Chicago. He’s really a fun collector, and I love guys that have a big heart, and he has the same attitude with keyboards and pedals and drums, and the Loft is just a super-cool place to hang out.

Do you have any thoughts on the way bass playing has changed since you started?

You just have to look on Instagram and you’ll see a million young players—female and male—that have astounding dexerty. A lot of them are playing 5- and 6-string instruments. There’s this whole proliferation of players going beyond the 4th string, and there’s a whole new school that’s going to take it to a very interesting place. A lot of them stylistically aren’t exactly my cup of tea, but I really appreciate the way they’re playing and the fact that there’s such a movement of female bass players, especially. I saw Jeff Beck this summer and Rhonda Smith is such a monster player, and I love seeing that shift in the culture to more women being represented.

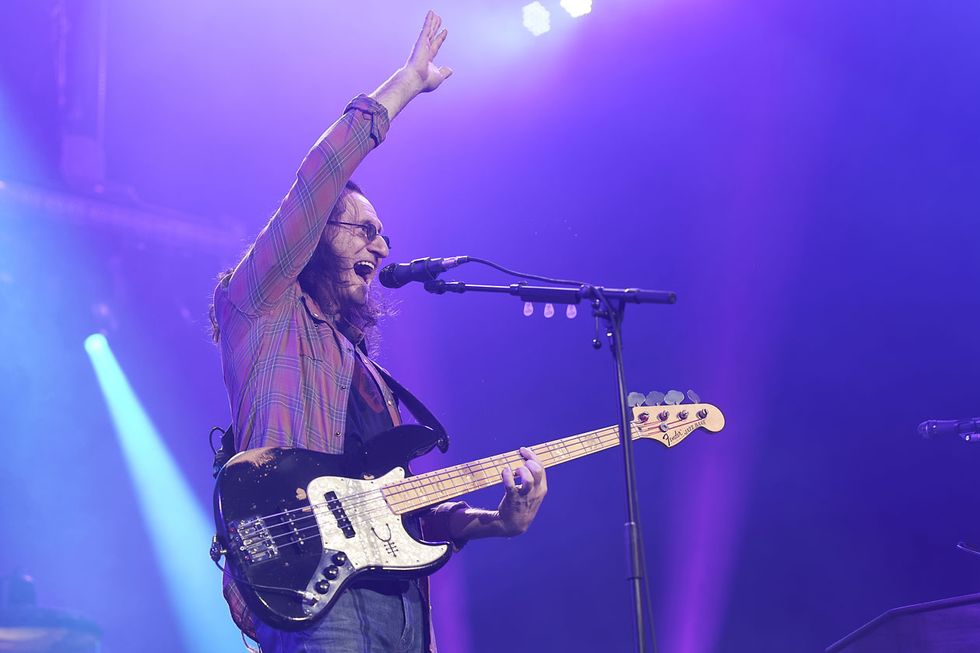

After decades of playing Rickenbackers, inspired by his hero Chris Squire, Lee adopted the Fender Jazz bass as his instrument of choice. Here, he wields one of his favorite J basses at the Palace in Auburn Hills, Michigan, on June 14, 2015. Photo by Ken Settle

You were called in to play in stay of your hero, the late Chris Squire, when Yes was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. What was that like?

Chris Squire was a hugely influential bass player in my life. He’s the reason I started playing Rickenbackers, and it was a combination of Chris Squire and John Entwistle, with a little bit of Jack Casady thrown in, that really led me down the sonic path I chose. So when I was asked to play with Yes, it was an incredible experience. I was blown away to be asked, and when I heard the lineup for the set included Rick Wakeman, Jon Anderson, Steve Howe, and Alan White—as close as you could get to the most profound version of Yes, in my world—it was such a huge thrill. It was also a real challenge, because we did “Roundabout,” which is one of the greatest bass songs ever written. I practiced the shit out of that song before I met up with the guys in New York, and it was just a real thrill.

It was also bittersweet, because Chris Squire passing so early in his life left a huge, gaping hole in my world. Between Chris, Jack Bruce, Greg Lake, and John Wetton all being gone, we’ve lost a lot of amazing bass players in the last 10 years. It’s really sad, and playing with Yes was a reminder that Chris wasn’t there to enjoy that moment himself. I felt like I just wanted to do right by him and honor him and really play the song properly. It was a great experience meeting the guys at the Hall of Fame induction, and they were very kind to me and very respectful, and just being onstage and looking over and getting nods from Steve Howe was a very cool moment in my life.

I’ve heard that Chris Squire was in the running to produce a Rush album at one point, but when he showed up to a gig at Wembley, he was seated next to Trevor Horn, who was also being considered, and things got awkward between the two of them. What’s the reality of that story?

That’s not exactly how it went, but they did both come to see us play on the same night! We were due to interview Trevor to potentially be a producer, but I think Chris had come to the gig just to check us out. The sad thing is there were a few producer/engineers in the building that day, and I never got to talk to Chris, despite him being so close. By the time we had looked around and finished chatting with everyone, he wasn’t there. I actually never got to meet him face-to-face.

Do you know what you’re interested in doing next?

I’m afraid I don’t really have a plan at this stage. I don’t know where I’m headed musically. My attitude is that I’ve been part of an amazing collaboration with two guys that I have so much respect for and for so many years, and we were very purposeful in our time together. The book has been a very cool way for me to transition out of that scenario, and now I feel like I’m in a position to truly clear the deck and hit the reset button, and see what I have to say musically. I need to give myself time to experiment with that and see what comes out that I feel strong enough to be a worthy thing to do next. I have no idea where that’s going to take me.

When I mess around at home, I’m sort of all over the map. But that’s also usually how a Rush album starts. I don’t imagine that whatever I do next will be drastically different, but because I have more guitars now, I’m playing more guitar in the studio and getting ideas that way. Stylistically speaking, I never felt like I was missing anything in the context of Rush because anything goes in that group. When I jam, I jam all over the place, but whether or not I’m going to follow it any one specific direction in the future, I have no idea. I never had any musical frustrations in Rush. It was a totally fulfilling experience for me.

One of the hallmarks of Rush’s music is its technicality. Is there anything from the band’s catalog that you recall being particularly challenging?

There’s quite a few that were very much a pain in the ass to play! There are songs on Clockwork Angels that were very difficult. A song like “The Anarchist” doesn’t seem that complicated, but requires almost complete rhythmic independence between your voice and hands in order to play that bass part and sing that vocal part at once. A lot of the Hemispheres album was really hard to play live because my vocal parts were recorded in such a high key that it was really taxing—not my ideal key. Other songs, like “The Main Monkey Business” were really tough because every time you play that song, you play it sort of on a knife edge because there’s so many goofy changes. If you sleepwalk through that song, you’re going to be in big trouble. “One Little Victory” was also a really tough song to play. Not so much as a player, but as a band. Fitting into that song’s groove and coming out of the indulgent parts at the same time is tough. I like that about playing live, and I like being on that bit of a knife edge—the stuff that requires a panicked look between each other as we’re coming out of the harder passages. Songs like “Working Man” are fun to play, and there’s all kinds of improv going on but it’s a fairly straightforward song. The highly structured songs, like “Mission,” really keep you on your toes.

The instrumental stuff is always so precision-oriented that it really came down to being well-rehearsed, and Rush was a fanatical rehearsal band. Many people would consider Rush’s rehearsal schedule over-rehearsing, but we didn’t feel that way because we wanted to be able to relax into our parts, and in order to do that, you have to know those parts inside out.

Do you have a favorite recorded bass tone from Rush’s discography, and has that changed now that you’ve experienced so many world-class instruments?

That’s a really tough one. I think the bass sound on “Tom Sawyer” is pretty ideal, and “Red Barchetta” as well. There are so many records to go through, and I was always fucking around with my sound in one way or another. Every time I thought I was plateauing, I would change something about it … which can be good and bad. That’s one of the dangers of being a progressive musician: You move past something you maybe should stick around in a bit longer because you’re busy searching for that next thing, that improvement. So always, as a band, the three of us were looking to improve from the last piece of recorded work.

Among the many things I’ve learned through this process of collecting is an appreciation for instruments and sounds that don’t necessarily fit in my typical soundscape. I avoided those instruments for over 40 years, and on the last tour I brought some of them out with us. Gibson Thunderbirds, for example. I never wanted anything to do with a Gibson Thunderbird because I always felt like they were antithetical to my sound in Rush, but I found moments that I could play those instruments in the context of Rush and really make it work. That was really enlightening for me, and I hope to play around with more of those particular instruments.

How would you like Rush’s music to be seen and remembered by future generations?

Obviously Rush was, in many ways, an ongoing experiment, so there were moments where the experiment achieved a kind of synchronicity and there are some albums that end up being arrival points. Moving Pictures, Permanent Waves, and even Clockwork Angels to a large degree are those kinds of albums. Someone once said that every artist deserves to be judged by their best work, and I sort of agree with it and would ask that we’re remembered by our best work and really our spirit, and that we had a willingness to experiment publicly. When you experiment publicly, you have to be willing to fail publicly and I think that’s an important thing for young musicians to appreciate and understand, and I think it went hand-in-hand with the successes of our career.

Geddy Lee speaks with Tom Power, host of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s arts and culture show q, about his experiences hunting for, and playing, some of the instruments in his Big Beautiful Book of Bass.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)