Photos by Ken Settle

If there’s one band on the planet that’s made it cool for musicians to be … well, uncool, it’s Rush. Because let’s face it—the intelligent, chops-heavy prog rock that Geddy Lee (vocals/bass/keyboards), Alex Lifeson (guitars), and Neil Peart (drums/lyrics) have become synonymous with over the last 30-plus years will never completely escape the stigma of being considered overwrought, stodgy, and even nerdy.

But with 1980’s “The Spirit of Radio”—a tune that the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame ranked as one of the top 500 most genre-defining—the dudes raked in fame and glory with brainy, multisyllabic bashing of the very industry and medium that made their careers possible, and they did it over a backdrop of swirling pull-off licks, distorted bass, and tour de force drumming that was somehow still catchy. Their encore? The next year they pilloried modern society at large with “Tom Sawyer”—a chops-laden, darkly futuristic anthem that even hardcore deriders of prog can’t help but dig.

Today, Rush is arguably the longest running, most original, and most influential progressive rock band ever. Their influence can be heard in major bands ranging from Pantera to Smashing Pumpkins, Primus, Death Cab for Cutie, the Mars Volta, Coheed and Cambria, and countless others. And yet, through innumerable musical fads they’ve remained staunchly committed to big ideas, grand arrangements, and stellar, instantly identifiable musicianship—rich, unorthodox chording, odd-meter riffing, and ethereal solos from Lifeson, and a finger-busting mix of Jack Bruce’s beef, Jaco Pastorius’ finesse, and a funk master’s groove from Lee. But they’ve also been flexible and open-minded enough to not come across as stagnant and stubborn. In the process, they’ve managed to get more radio play than just about any of their peers, scoring bona fide hits with songs like “Fly by Night,” “Closer to the Heart,” “Freewill,” “Limelight,” and the aforementioned classics. But even when their collective open-mindedness led to sonic evolutions that didn’t sit well with some longtime fans—specifically, the synth-heavy output from 1982–1989 that seemed to push Lifeson into a more atmospheric and textural approach—the band has remained unapologetically forward-looking.

With the release of this year’s Clockwork Angels, the Canadian legends prove they haven’t changed their devil-may-care attitude one bit. A steampunk concept album that finds the band bringing subtle keyboard and piano elements back into the mix, Clockwork is chock-full of classic Rush hallmarks—from Lifeson’s gloriously echoing, “Limelight”- like solo in “The Anarchist” to Lee’s jaw-droppingly nimble-fingered breakdown in “Caravan” and the newfound fire in Peart’s drum work. But there are also fresh elements that make it perhaps the band’s most listenable outing in years. Lee’s singing, particularly on the beautifully simple “The Garden,” exhibits more control and nuance than on any other Rush record, and several songs are augmented with lush string arrangements.

We spoke to Lee and Lifeson at the tail end of the seven-week rehearsals for their current world tour about everything from the writing and recording of Clockwork to the secrets of their longevity and their extreme gear nerdery—from Lee’s Orange amps and ’72 Jazz-bass fetish to Lifeson’s recent addiction to Marshall Silver Jubilee amps.

Was there anything unusual about how

you recorded Clockwork Angels?

Lee: Only in the sense that, listening back

to [2007’s] Snakes and Arrows, I saw a record

that we probably had more overdubs than we

needed. I think that comes from underestimating

the fullness of the sound of the three

of us playing. So, having the benefit of touring

quite a bit from the time we made that

record, and to play some of the new material

that we’d written on tour, we learned a lot

about ourselves. I think the live experience

has informed our writing over the last few

years. This album is a direct result of that.

You’re not talking about overdubs of things

like solos, though. You’re talking about layers—

numbers of overlapping parts.

Lee: Yeah, layers. We just had this tendency

to hear music in a dense way, and I think

that even though we streamlined the way

we were writing, we were choking some of

the parts—some of the interesting stuff was

being obscured by too many parts. So when

we approached this record, that was very

much in the back of our minds. If we were

going to have an overdub, we better have a

damn good reason.

That said, Alex, you’ve really perfected the

art of layering guitars with different timbres

and tonalities. How much of that do

you hear when you’re writing tunes, and

how much of it comes to you as you’re into

the track up to your elbows in the studio?

Lifeson: A lot of it does come to me

beforehand. I hear a lot of things—and

then, once I start exploring, I hear a lot of

other things [laughs]. But that’s the real fun

for me. I can sit and do that sort of thing

for hours and hours and hours. I’m always

looking for something that nobody’s ever

heard or trying to take a sound and modify

it in a way that’s fresh and different.

Some of the new songs—like the title

track—have a really live, spontaneous feel.

Did you track any parts together this time?

Lifeson: Sometimes, but not very often.

Typically, Ged and I will work in [Apple] Logic

with a drum machine or samples, and then

we’ll give that to Neil and he’ll work on his

drum arrangements, and then we’ll develop it

from there. But with this record, we gave him

the music and there ended up being a lot of

changes in the lyrics as we went along. When it

came to actually recording, Nick [Raskulinecz,

co-producer] wanted to record off the floor

from the first day forward—which was really

unusual and a big surprise for Neil, but he

embraced it and ended up loving it. His playing

is just a lot wilder and less thought out. It’s

more reactive to music that, in a lot of ways,

he’s hearing for the first time. Nick really prodded

him to take different approaches—so it

was really quite a palette. Consequently, when

he’d get drum tracks done at the end of the day,

we’d import them back into Logic, and then

redo our parts to what he’d done, and we’d

bounce back and forth like that a couple of

times … sometimes four or five versions. And

then, once those drum parts were established,

we’d go in and redo all our parts.

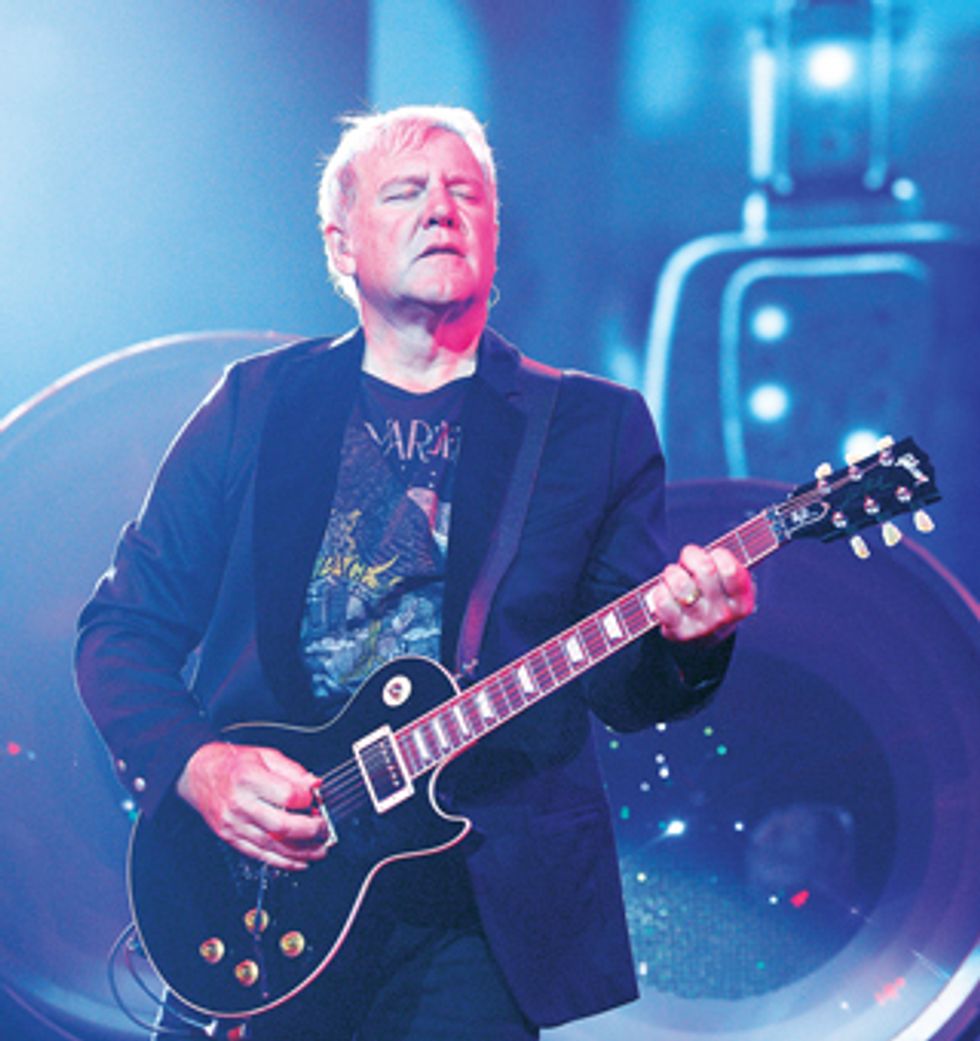

Alex Lifeson basks in the echoing glory of his favorite new signature Les Paul at a September 18 show in Auburn Hills, Michigan. “I gravitated to [it] for probably 60 percent of the record,” he says.

This is the way we’ve worked for a long time—we seldom work off the floor. For us, it’s much more efficient and pleasurable to work in this manner where we have our own space in the studio, we can focus on what we’re doing, and you’re not doing take after take after take because somebody slipped up somewhere and you have to go back and start over again. We’ve tried doing it live, and it’s kind of fun—and I understand the merit in it—but for the complexity of our music and the focus that’s required, it’s much more efficient to work this way. We’re all there—everybody’s in the studio at the same time, and everybody’s a cheerleader—but the actual performances work better this way. Once you’re used to is, it’s just as satisfying as playing live, but it’s easier because you’re not struggling to hear yourself and all those things that just defeat the purpose of why you’d do it live anyway. If you’re going to do it off the floor, you better do the take perfectly right from the start.

Did that new MO about minimizing

overdubs affect Alex’s parts primarily,

or did it also affect bass lines?

Lee: If you’re limiting the amount of keyboards

you’re going to use—which seemed

to be a mandate early on [laughs]—then it

falls down to the guitar player to fill out

the sound. I thought we could get away

without that, and Alex agreed a hundred

percent. By the same token, he had strong

feelings about my layering: For a few

records there, I was really layering my voice

with multipart harmonies all the time, and

he wanted to see a more direct approach

with my vocals this time—less harmony, or

at least just very specifically used harmony.

Did that change in how you approached

the vocals affect how you approached the

bass parts?

Lee: Not really. The bass kind of goes where it

needs to to make the song vibrant—what the role

of the bass is changes from song to song. In some

moments in the song, “The Anarchist,” for example,

that bass melody holds that chorus together.

So that was driving the chorus, and when I wrote

the vocal melody it really had more to do with

how those lyrics needed to be expressed, and I

found to my dismay [laughs] when I came to

rehearse them, that they were very difficult to

do at the same time. I feared that bass line, and

I made sure I went into rehearsal extra early

this year. I’m a big believer in the 10,000-hour

series—I put a lot of hours into that!

In the past, I wrote bass patterns that were connected to the vocals in a way that allowed me to do it live without killing myself or tying my brain into a pretzel, but this time I kind of let that go because I just felt it was better for the music to go where it needed to, and worry about the best possible vocal melody for the song afterwards. So that’s how it came together—as two separate players: Me, as a bass player on this album, was a separate guy than me as a singer.

Was that bass part in “The Anarchist”

difficult because of the physicality of the

fingering or because of the conflicting

harmonies and rhythms?

Lee: It’s the syncopation—or the lack of

syncopation. Rhythmically, the way the

bass drives and the way the vocal sits on it

are really quite different.

In the intro to “Clockwork Angels,”

it sounds like the synth intro to “The

Camera Eye” [from Moving Pictures] is

playing backward in the background.

There’s also an ascending, flanged unison

riff near the beginning of “The Anarchist”

that sounds like a nod to “Red Barchetta.”

Are these intentional nods to the past, or

is it just a coincidence due to the fact that

it’s coming from the same guys?

Lee: No, there are some not-so-subtle nods

to the past, like, in “Headlong Flight”—which is a very obvious “Bastille Day”

redux—but what you’re describing I think

is just coincidence.

John “Skully” McIntosh, bass tech for Geddy Lee for the past three years, was on hand to take care of both the basses and guitars during the Clockwork Angels sessions. Here he details Lee’s main gear for the new album and tour.

All That Jazz

Lee’s No. 1 bass is a black ‘72 Fender Jazz bass

“that has been seen time and time again, onstage

and in photos, and to which all other bass guitars

are compared,” McIntosh says. “This instrument

carries most of the weight during the show.”

The pickups are original, though the bridge pickup was rewound to virtually original specs by Tom Brantley at Mojo Tone in North Carolina in 2010. That same year, it was outfi tted with its third neck—a maple Fender Custom Shop version with a 9" radius, white binding, and aged pearl block inlays. According to McIntosh, it has “a little more mass than the typical Geddy Lee-style neck,” and like all of Lee’s basses, the back of the neck has a rubbed oil fi nish. It’s set up very straight, with extremely low string height and fast action. The medium-weight alder body features an aged pearl pickguard custom-engraved by James Hogg with the alchemical symbol for amalgamation. Says McIntosh, “All the touring basses have scratch plates engraved and paint-fi lled by James with various alchemical symbols.” Like all of Lee’s Jazz basses, No. 1 has a Badass II bridge.

Lee’s No. 2 bass is a sunburst ‘72 Fender Jazz with a neck made by Mike Bump at the Fender Custom Shop in 2011. It’s used as his main backup and for “Seven Cities of Gold” and “Wish Them Well” off the new album. Like No. 1, it has a 9"-radius maple fretboard, but the binding and block inlays are black. Its pickups were made by Brantley at Mojo Tone and are based on No. 1’s.

When performing “Bravado” (from Roll the Bones), Lee plays a black ’74 Jazz with a neck just like that on his No. 1. “It has the original pickups,” McIntosh says mysteriously, “but with a little voodoo inside to get just a little something more out of them.” All three ’70s basses have the original tuners and string trees.

Lee’s “elegant” candy apple red Fender Custom Shop Jazz bass has an ash body with a maple cap. It has a slightly narrower neck than his ’70s basses, but still has a 9"-radius maple fretboard. “This bass has been around for a while and has Custom Shop pickups in a ’60s-style spacing,” McIntosh explains. Lee uses it for “2112,” as well as “Halo Effect,” “The Wreckers,” and “The Garden” from Clockwork. His backup for the red Jazz is a sunburst Fender Geddy Lee signature bass.

For “The Pass” (from 1989’s Presto), Lee plays a D-tuned black Jazz bass assembled from parts—including a Mike Bump-built Custom Shop neck and pickups by Tom Brantley. McIntosh says Lee also recently received a new Custom Shop surf green Jazz bass built by Jason Smith that will be used on four songs.

All of Lee’s basses, regardless of tuning, are strung with Rotosound Swing Bass RS66LD (.045–105) sets, and they’re outfitted with Levy’s Leathers straps and Jim Dunlop Straploks.

A Clockwork Orange ... and Sansamp, Palmer, and Avalon

McIntosh says Lee’s Clockwork tour amplification

rig is unlikely to change much from the

previous tour. “However, you can never count

out the possibility of a change or addition of a

piece of gear. The bass rig is an ongoing evolution

that will never cease.”

Lee’s signal goes through a Shure UHF-R system that’s switched via a Kitty Hawk MIDI Looper to an Axess Electronics splitter. “From there, the signal goes out in parallel to a SansAmp RPM preamp, a Palmer PDI- 05 speaker simulator, an Avalon U5 DI, and an Orange AD200 MK3 amplifier—which, in turn, drives another Palmer PDI-05. A Rivera RockCrusher power attenuator provides a load for the Orange. These four lines then run direct to the P.A.” Lee and McIntosh prefer running the Orange with new-oldstock GE 6550 power tubes. “They have a little less warmth than the [JSC Svetlana] ‘winged Cs,’” McIntosh explains, “but they have more clarity and sparkle in the high end, which works better with the high-gain distortion setting we run the amp with.”

For the Clockwork Angels sessions, an Orange 4x10 cabinet was mic’d in place of the second Palmer and RockCrusher used on the road, but McIntosh says that, on the current tour, Lee isn’t using speaker cabinets in his bass rig. Further, the band isn’t using any monitors onstage other than the subs that augment the Logitech Ultimate Ears in-ear monitors they all wear.

“On tour, this arrangement is supplemented by Brad Madix at F.O.H. [front of house mixing] and Brent Carpenter on monitors,” says McIntosh, “who each add a fifth channel of tweed-Bassman-flavored amp modeling through the console." McIntosh also says that, other than subtle changes dialed in by Madix or Carpenter, Lee’s bass-rig settings do not change from song to song.

How do you choose when and what to

reference in those nods to your back

catalog—is it just spur-of-the-moment

studio cheekiness?

Lee: Yeah, it’s a bit of cheek. But, also—like

with “Headlong Flight”—it was kind of an

accident: Alex and I were jamming, and we

go, “Oh, [expletive]—did we just rewrite

“Bastille Day”? [Laughs.] Because we had

assembled that into a complete instrumental

song at that point, and at first we were

happy to let it be kind of a cheeky nod to

the past. So the song was finished, but then

I got lyrics from Neil and realized that, at

this part of the story, [the protagonist of the

album’s storyline] is looking back over his

life and thinking back over his life—thinking

about things that he regrets, things he

doesn’t regret—and the main line is “I wish

that I could live it all again.” So, it seemed

oddly appropriate that we were reminding

ourselves of where we’d been, too.

Alex, how did you get that choppy

effect on the guitar at the beginning of

“Clockwork Angels”?

Lifeson: That’s from one of the plug-ins I

use. It was doing this funny thing where,

when you’d go through the song and then

stop and go back to the beginning and

hit play, that effect would happen. It’s not

recorded as part of the file, but it’s like an

artifact or a regeneration of the plug-in that

would always happen unless you went to the

end of the song and ended it. We kind of got

off on it, and Nick loved it, so he said, “Let’s

start the song with that thing!” I used an

atmospheric Guitar Rig plug-in for the “As if

to fly … ” section just before the bridges, too.

Which guitars did you use on that song?

Lifeson: I used my ’76 ES-355 for all the verses—I love playing that guitar, and it sounds

really, really good. It’s such a ballsy, woodsy

sound. I used that quite a bit on the whole

album. I used my Gibson J-150 for the slide at

the end of the solo. I used a ’59 Tele reissue for

most of the clean stuff on the album, like the

cleaner bridge parts of that song, and then

the Les Paul on the “As if to fly” parts.

The openings of “Carnies” and “Wish Them

Well” have some of the most ferocious guitar

tones on the album—the latter has a bit of

a snarling, Angus Young vibe to it.

Lifeson: We were going for that big, open

rock vibe with “Wish Them Well.” That song

went through three complete rewrites. We

just weren’t happy with it as we went along,

but finally it came together and had the kind

of vibe that we wanted at that point in the

record. I think I used my ’59 Les Paul for

that. It was really a lot of fun to record that,

because there are those big, open rock chords,

and Neil’s drumming is just so straight ahead.

On “Carnies,” it’s riffy at the beginning, which I quite enjoy, and then there’s the choruses. And there, again, I used a Guitar Rig plug-in on one of the guitars, and it sounded a bit like a carousel.

Was it a rotary-speaker plug-in?

Lifeson: It’s in their special-effects listing,

and it’s called “Soundtrack” or something

like that. It has so much junk on it—it has

sort of a rotary sound, and it fades in and

out, and it’s manipulated in so many ways.

I was drawn to it because it had the sound

of a merry-go-round …

So it sort of mimicked the chaos and

craziness of a carnival …

Lifeson: Yeah, yeah, exactly.

The intro to “BU2B2” has a bit of a

spaghetti-Western vibe with the acoustic

and the slow, tremolo’d electric—that’s a

new feel for a Rush album.

Lifeson: Oh, yeah that—I forgot about that!

[Laughs.] That was fun to do. We were in

L.A. mixing the record, and we wanted to

insert this little bit of a lyric or a presence

that Neil wanted to have in there, and we

thought, “How can we add to it without

taking away, and make it something different—but not another song?” So we recorded

that in my hotel room, Geddy and I. We

stuck the mic outside and recorded the

morning traffic and sounds of Los Angeles

from our hotel room, and then I did the

acoustic tracks and threw a vocal track on it.

The tremolo-picked chords in the verses

of “The Wreckers” are also sort of a

new feel for you guys—there’s a hint of

romantic, traditional Italian or French

music. What inspired that?

Lifeson: We struggled to get something to

feel right in those verses. I was playing arpeggios

and block chords, and everything sounded

clumsy and nothing was working. After a

few hours of experimenting, I just turned the

volume down a little bit and we got a shimmery

sound, and I just did this fast strumming.

It seemed to fit the mood really, really

well. It didn’t get in the way of anything, and

it provided a nice foundation for Geddy and

Neil—and the lyric, especially.

Let’s talk gear for a bit. Geddy, you have a

history of being pretty adventurous with

bass choices—from the Rickenbacker

doubleneck you used on “Xanadu” to

your Steinberger and Wal basses in the

’80s. Even though you’ve been relying

on Fender Jazz basses for the last several

years, have any new, off-the-beaten-path

instruments caught your eye recently?

Lee: I’m pretty hardcore Fender right now. I’ve

had a few instruments given to me that I’ve

played with. I’ve got a beautifully made Spector

bass that I’ve played around with and quite

like, but it doesn’t sound like how I want to

sound right now. Aside from that, not really—I’ve just been getting deep into Fender land.

Do you ever break out those old basses—the Rick, the Steinberger, or the Wals?

Lee: I do. For this album I pulled a lot of

things out to see what they would sound like.

In fact, we got very heavily into the differences

between Fenders themselves—because I have

a lot of different kinds of Jazzes. Skully—John

McIntosh, my tech—has been working with

Fender to put together different kinds of pickups.

At one point, before we started recording,

we actually had five different vintage Jazz

basses, and we were A/B’ing them with the

exact same riffs, just to get into the nuances

of how different they sounded. And they

do sound quite different—even though, to

the layman, it might be quite esoteric—but

we quite noticed all the differences and

used them appropriately on this album.

I used about four different Fenders while

making this record.

What can you tell us about those four?

Lee: My No. 1 Jazz bass is from ’72, and

I used that on the majority of the songs. I

have another ’72 that I found recently in a

shop in Toronto. We cleaned that up and

Skully put a different set of pickups in it,

and it has a bit more of a raw sound—a

little less deep and a bit more alive—and

I used that on “Seven Cities of Gold” and

“Wish Them Well.” I really like it—I’m

playing it live, as well. It doesn’t quite have

the punch in the bottom end that my No. 1

has, but it’s got a nice midrange growl to it.

I also have a red Fender Custom Shop Jazz bass that I use that, for some reason, just has a deeper tone and a little less spiky top end—or more elegant top end. I guess “elegant” is a weird word to use in a rock band, but anyway … [laughs] I use that for some of the softer things, like “The Wreckers” and “The Garden.” And then I also have a ’74 Jazz bass that I found, and it has a really interesting sound. It’s deep, kind of like my original ’72, but it doesn’t quite have all the same attributes. I’m using all of those live, as well [see sidebar for a complete list of Lee’s gear].

Is your No. 1 1972 bass stock?

Lee: Pretty much. We’ve tweaked the

pickups over the years—only when they

kind of break—but I try to keep it as true

as possible to the original instrument.

Is it just a coincidence that your two

favorite basses are ’72s, or have you

pinpointed something about Jazzes

from that year that you really like?

Lee: Well, I’ve had such a hard time replicating

the sound I get out of my [first]

’72 that I’ve been looking for another

bass from that period to see if they

match. So I found this other ’72, which

happens to be a sunburst. They use different

wood, usually, when it’s a sunburst

than when it’s a painted body—obviously

for the grain. But these two are only a

few hundred numbers away from each other,

in terms of their serial numbers, so it’s very

odd to me that they don’t sound exactly the

same, and the only thing I can put it down

to is the wood and the aging of the wood.

Alex, how long have you had the Tele

you used for the clean parts on the new

album—and is it all stock?

Lifeson: I’ve had that one for about 20

years, and it’s got a Badass bridge, and the

neck has been sanded down to bare wood. I

think the pickups are stock, though.

Did you find yourself gravitating to one or

two specific guitars for the whole album,

or was it all over the map?

Lifeson: It’s funny—I got one of my All

Axcess [Les Paul] models that they’d done in

black, and it was one of those guitars where

you go, “Holy shit—this thing sounds amazing!”

I like the way they all sound—I’m very

happy with them and we worked really hard

to make a really good guitar—but this thing

just sounded so good through every amp I

had in the studio. I gravitated to that guitar

for probably 60 percent of the record.

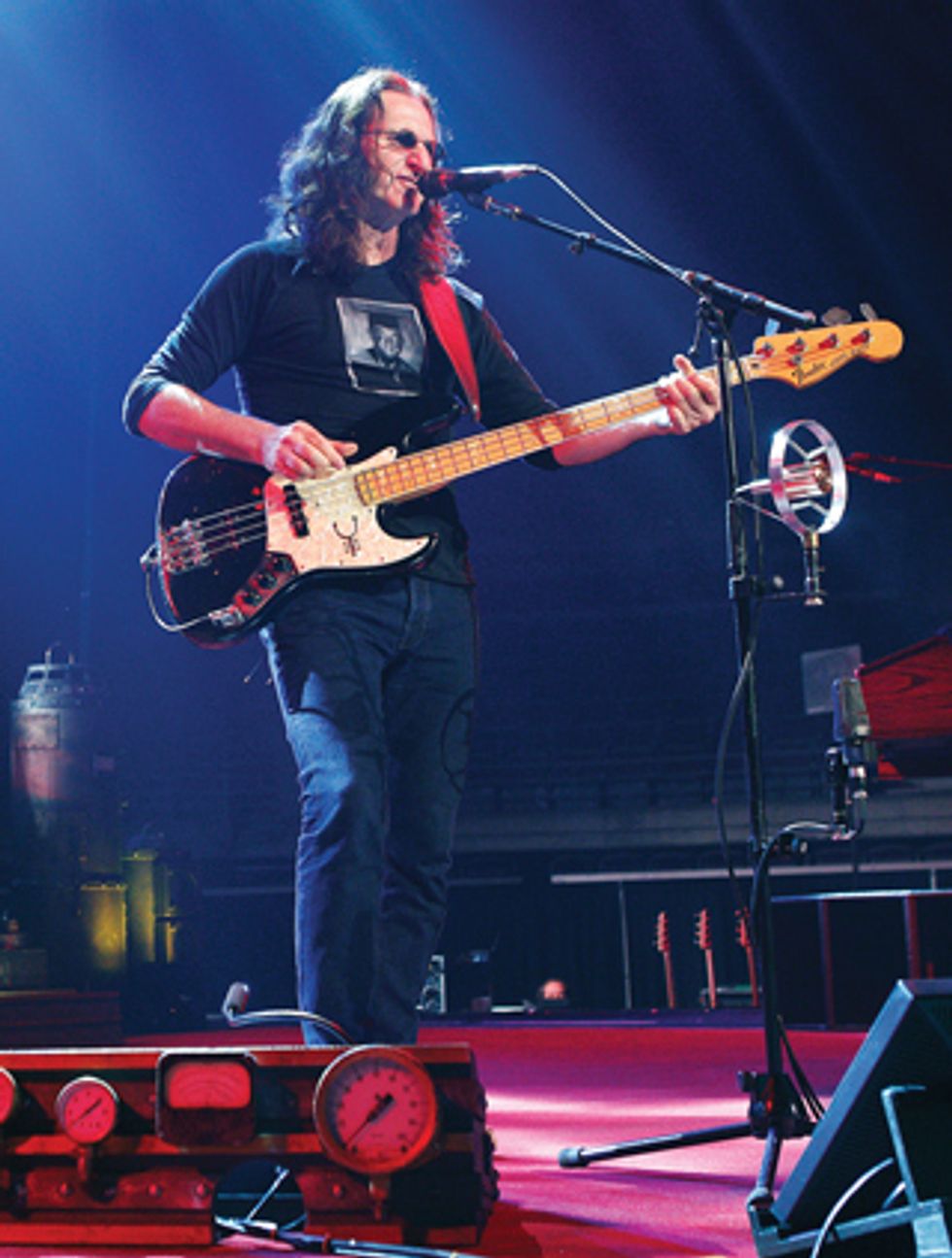

Geddy Lee plays his No. 1 ’72 Jazz bass while working a Korg MPK-130 MIDI Pedal Keyboard housed in a retro-sci-fi custom pedalboard case.

Does it have the same specs as your other

signature guitars?

Lifeson: It’s funny. After I played it for a bit,

I emailed Pat Foley at Gibson and I said, “Pat,

what’s up with this guitar? It sounds amazing!”

And he said that sometimes it’s just the

combination of the wood and the way it’s all

put together, but he also said they wanted to

do a small run of solid-color models. There

were requests for that, but sometimes you also

get an imperfection in the finish of one of the

translucent ones, so they do a solid color on

it to save the guitar. Something happens with

the solid colors—there’s more paint on it, and

maybe that has something to do with it, but

everything else is the same. Whatever it is, it

just has a nice growl to it. It translates really

well—you really get a sense of the pick against

the strings. It’s got that little grit to it.

So Alex, you mainly used the Tele, the

355, and the black Axcess Les Paul?

Lifeson: Yeah, but I probably used 20

guitars on the record [see sidebar for a complete list]. I used a

beautiful PRS electric 12-string—it sounds

fantastic and is so lovely to play. I had the

Ricky 12-string, which is exactly the opposite.

It’s a nasty, angry guitar that does not

want to stay in tune and bites my fingers—but it looks so cool! [Laughs.]

Let’s switch to amplification. Geddy, did

you use DI boxes and amps in the studio?

Lee: Yeah. I used a whole combination of

devices, and I bring them up on separate

inputs. I use a Palmer speaker simulator on

one input, a SansAmp RPM on another,

and the Orange amplifiers on the other.

Basically, I set it to “stun” in the room!

How does your touring rig differ from

what you used in the studio?

Lee: It’s pretty much the same. Brad Madix,

our front-of-house sound guy, has all those

separate rails, and he can mix and match

them according to the song.

Alex, you’ve been a pretty stalwart Hughes

& Kettner guy for a while now. Did you

use them again for this album?

Lifeson: No, I didn’t. I made a change this

year. I used a Marshall Silver Jubilee 2553.

It’s a 25-/50-watt amp from the ’80s. I also

used one of the new Mesa/Boogie Mark Five

heads—it’s got, like, nine amps in it. I loved

the way that sounded for all the clean stuff. I

also had a 50-watt Marshall, Marshall 2x12

combos that I got way back in the ’80s, a

Bogner, and other stuff.

I’ve used Hughes & Kettner gear for quite a few years, and I love their equipment. It’s excellent, and they’re great people to work with, but I felt that after so many years it was time for a change. I really wanted my guitar sound to be a little different this tour. So I started out with that setup—the Boogie and the Marshall, with a Hughes & Kettner Coreblade to augment some different effects. And then Skully found this company [Mojo Tone] that handwires amps in North Carolina, and they built me an amp called the Lerxst Omega—Lerxst is my nickname—and we based it on what I liked about that Marshall. It sounds fantastic. Really nice saturation, great warmth. I’m really, really happy with it. I think part of the reason I got tired of Hughes & Kettner is that we were running three channels in the one amp, and I was finding that when I was switching between the channels I was getting some noise—thumps—and after hearing the Marshall I thought the sound was a little bit thin, a little processed compared to a screaming, single-purpose amp. I understand that that’s a bit of a compromise, and it’s certainly no reflection on the Hughes & Kettner gear, but it was time for a change for me.

Did you use the Lerxst Omega in the

studio, or is it just for the tour?

Lifeson: No, that didn’t come out until

we were in our final stage of rehearsal.

I used the Marshall for the primary

rehearsals for six weeks, and then that

arrived and, sadly, the Marshall now

resides in a case somewhere [laughs].

So which amps are you taking on the road?

Lifeson: I’m taking the Lerxst and a

backup, a Mesa/Boogie Mark Five and a

backup, and a Coreblade with a backup.

I’m also using [Apple] MainStage, so I’m

accessing all the Guitar Rig plug-ins and

Universal Audio plug-ins—which, by the

way, are just awesome plug-ins.

One more gear question: Alex, you’ve

always been a purveyor of gorgeous

washes of delay. What’s your favorite

delay device right now?

Lifeson: Right now I’m using Fractal

Audio Axe-Fx IIs for just about all of the

outboard effects. I have two delay patches,

two other patches—one for reverb and one for

reverb/pitch [changing]. And for forever I’ve

been using the TC Electronic 1210 [Spatial

Expander + Stereo Chorus/Flanger], and I love

it. I’m using that for my phasing and flanging,

and using the Fractal for the chorus.

Guitars

Black Les Paul Axcess signature model, black Les Paul

Custom, goldtop Gibson Les Paul, 1976 Gibson ES-355, red

Gibson Custom Alex Lifeson Les Paul Axcess, sunburst Les

Paul Axcess signature model, ’59 Fender Telecaster reissue,

Martin 12-string acoustic (tuned to D–A–D–A–A–D for “The

Pedlar”), Larrivée acoustic (for slide on “The Pedlar”), Gibson

ES-345, Gibson J-150 acoustic, Gibson Les Paul Junior, 1958

Gibson Les Paul Standard, Gibson ES-175 (in Nashville tuning

for “Wish Them Well”), Taylor acoustic (in Nashville tuning

for “The Wreckers”), 1959 Gibson Les Paul Standard, Three Gibson Custom Alex Lifeson Les Paul Axcess signature

models, ’76 Gibson ES-355, one Gibson Les Paul

Custom, one Gibson ‘58 Les Paul reissue, one Gibson

‘59 Les Paul reissue with a Floyd Rose, one Gibson Les

Paul Custom with a Floyd Rose, one Fender Custom Shop

Telecaster

Effects

Electro-Harmonix Big Muff (for “The Anarchist” solo), MXR

Flanger, MXR analog delay, Boss Flanger, Electro-Harmonix

Memory Man, Boss Compressor Three Fractal Audio Axe-Fx IIs, TC Electronic 1210 Spatial

Expander + Stereo Chorus/Flanger, two Apple 2.6 GHz MacBook Pros running Apple MainStage UAD plug-ins and Native

Instruments Guitar Rig 5, two Universal Audio Apollo QUAD

audio interfaces, Jim Dunlop Cry Baby Rack Module wah

Amps

Marshall Silver Jubilee 2553 head, 50-watt Marshall reissue

1987X plexi head, tall vintage Marshall 4x12, Mesa/Boogie

Mark Five head, Marshall 1960X 4x12 reissue, Matchless

Clubman, Hughes & Kettner straight-front 4x12, Roland

JC-120, Marshall Club and Country combo (used to drive

a 4x12), Bogner Uberschall, 18-watt Marshall combo, Vox

open-back 4x12 cab, Two custom Lerxst Omega 50-/25-watt heads based on

Marshall 2553 and 2550 Silver Jubilee heads (built by Steve

Snyder at Mojo Tone), two Mesa/Boogie Mark Five heads,

two Hughes & Kettner Coreblade heads, three Palmer PDI-

03 speaker simulators

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

Dean Markley electric strings (.010–.046 and .010–.052

sets), Dean Markley acoustic strings (.012–.054 sets), Jim

Dunlop medium picks, George L’s cables, Dean Markley electric strings (.010–.046 and .010–.052 sets),

Jim Dunlop medium picks, George L’s cables, Levy’s Leathers

straps, Embrace guitar stands, three RJM Music IS-8

input selectors, four dual Audio-Technica AEW-R5200 wireless

units, two RJM Music Amp Gizmos, one Mesa/Boogie

High-Gain Amp Switcher, Behringer MultiGate Pro XR4400

Quad Expander/Gate, RJM Music Effect Gizmo, one Furman

AR-PRO AC line-voltage regulator

Okay, let’s talk bigger-picture stuff.

Geddy, how would you describe Alex’s

evolution as a musician up to this point?

Lee: I think he’s underappreciated for the kind

of complexity he brings to his guitar playing.

Not only is he an amazing soloist—and always

has been—but he’s developed a very interesting

rhythmic and harmonic style of chord

creation. He’s constantly searching for ways of

bringing more musicality into the chord itself,

and he’s always experimenting with different

tunings. I think he’s evolved into a very interesting

and deep guitarist. Y’know, we grew up

in a period when it was all about the soloist—he loved Jimmy Page and Ritchie Blackmore

and all those guys—and of course he was very

influenced by that and became a great soloist.

But when you’re playing in a three-piece band,

you have to develop good chops to help fill

in the sound, be able to spread the chord out.

And that’s kind of pushed him to develop a

great sense of arpeggiation and developing the

technical side, where he’s got all these layers of

guitar sounds that he can draw upon to sound

like more than one guitarist while he’s playing.

Alex, same question for you about Geddy.

Lifeson: As a singer, he’s evolved in many

ways. He’s really become a singer. In the

early days—and, again, it was a different

time, a different physicality—he screamed

more, he hit those high notes. That was the

unique quality he had in the way he sang

and how he delivered lyrics. Now I’m more

drawn into the way he sings, particularly

on this record. There’s something that’s very

compelling in his singing—the nuances,

how he translates lyrics into vocal parts. It’s

really a skill, and I get to watch it all the

time. He works really, really hard on it.

As a bass player, he’s always been amazing [laughs]. He blows me away when I sit and watch him play. I wouldn’t know how to quantify his evolution and development, because I think he’s always been very busy, he’s always been all over the place—but at the same time, he knows when to pull it back and, y’know, sit down and let everything circle around him.

Final question: In a recent Rolling Stone

interview, Neil mused a bit about how

much longer he can pound the drums with

the sort of stamina that Rush requires. It

seems ridiculous to think there will be a

day anytime soon when he can’t crush most

drummers on the planet, but what do you

see for yourself whenever that day comes?

Lee: I didn’t see that interview, but I know

what he’s getting at: How much longer can

we go out there and play three-hour shows at

that peak level. And I can see it in him. Last

night, we were at the end of a very long day of

rehearsing—I don’t think we’ve ever worked

so hard prepping for a tour, we’ve really put

in a serious amount of hours—and I could

see he was tired. We were almost three hours

into the set, and we were deciding whether to

do one or two or three songs in the encore,

and there comes a point when you just have

to accept that you’re approaching 60 and that

maybe three hours of blistering rock is for

a younger man. That’s what he’s getting at.

So maybe it’s just inevitable that Rush tours

down the road—if all goes well and there are

Rush tours—aren’t three hours long [laughs].

Lifeson: That’s a very valid, prurient question. We’re thinking about this all the time. Every time we go to rehearsals, I think, “Wow, this has really been hard work this time. Why has it been so difficult?” And I know why it’s been difficult—it’s not the physicality so much as it is the mental work required to put Clockwork Angels together, plus all this other material we’re doing, plus working with a string section—two cellos and six violins—which, by the way, is absolutely awesome. But, y’know, it’s hard for him. We’ve been rehearsing for seven weeks, and I think we’ve had four, maybe five days off in that period—plus, he started rehearsing a month before we did. So he’s been playing constantly for months now. He’s going to be 60 next week, and it is a huge toll. I mean, he has an amazing stamina and he’s a very strong individual, but what he does is very, very difficult and very demanding. Hopefully, we’ll get through this tour with no problems—I’d like to think that we will, and that’s certainly our plan.

But eventually, one day, we’re not going to be able to do it anymore. That’s a reality, and I don’t think we should get too caught up in it. When it happens it happens, and that’s it. We’ve had a great run, we’ve left a great legacy that we’re proud of, and who knows what’ll come after that? I mean, I think my fingers will still work for a little while longer [laughs]. I like to do stuff at home, to work with other people and continue to be musical, but there are other things in life, too—especially when you’ve dedicated so much of your life to touring. There’s no doubt that we absolutely love what we do, and we know that we’re very, very fortunate to have been able to do this. But eventually it does come to an end. I don’t want to be 70 years old jumping around onstage. Maybe if we’re still making great music, sure. But I kind of doubt it by that point. Most 70-year-old rock musicians I see now are not really that enjoyable to watch.

Plus, even though Neil is 60, most

25-year-olds can’t play what he plays.

Lee: Well, yeah … [laughs].

Lifeson: I agree with you—and most don’t. Maybe he was being reflective. Y’know, he has a young daughter, and we all have given up a lot being on the road, away from our families. I have two grandsons who I adore and love being with as much as I can be, and I’m fortunate that they feel the same way—so it kills me to be away from them. And I know it kills him to be away form his daughter and miss those formative years, and it’s tough for her, as well. So these things kind of eat away at you. But, at the same time, you feel a responsibility to your art and your partners, and so you do it.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)