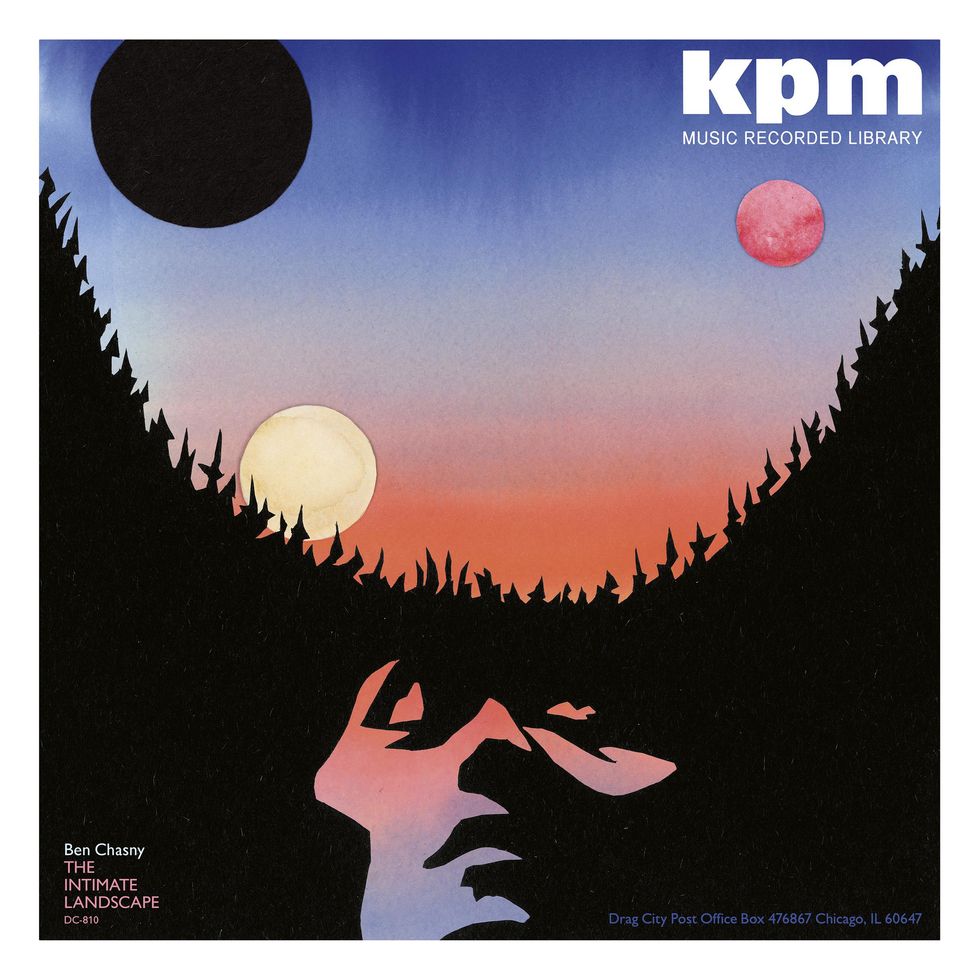

Ben Chasny has spent his musical life firmly rooted in the undergound. If you’re an avant aficionado, you might be familiar with his project Six Organs of Admittance. Or his band 200 Years. Maybe Rangda, New Bums, Badgerlore, or even Comets on Fire?

You get the point. Chasny is prolific. Over the past couple decades, he’s proven to be an unwavering devotee of the musical fringe. He’s a noise-rock experimenter, and his acoustic work is revered by the heaviest of metal communities. He’s even created a vastly complex system for composition and improvisation that you can learn about in his 2015 PG interview.

But Chasny is changing his M.O. with The Intimate Landscape. The first album to be released under his own name, it’s a collection of beautiful, melodic, and accessible acoustic fingerstyle songs. And they were all recorded in hopes that marketing agencies would buy them. Seriously.

Ben Chasny "Second Moon" (Official Song Visualizer)

How does a psychedelic noise warrior who grew up on the Melvins and built a career in dissonance end up here? According to Chasny, it goes back to one of his early, understated guitar heroes. “I actually played bass in punk bands. I never wanted to play acoustic, but when I heard the first few chords on [Nick Drake’s] Five Leaves Left, it blew my mind. It wasn’t the lyrics. It was the sound of his playing. He’s doing syncopated stuff between his thumb and his fingers that I’ve never heard anybody do. He’s someone with his own thing. You know immediately when it’s him. That’s when I wanted to play acoustic guitar. That’s what changed everything.”

Drake’s influence helped shape Chasny’s debut recording, 1998's Six Organs of Admittance, an album he initially tried to keep on the down-low. “At the time, I was getting very into ’70s cult stuff, like Comus and the Incredible String Band,” he explains. “I wanted to create that illusion of an anonymous acid-folk cult band, so I released it myself. And for the first couple of Six Organs releases, I didn’t put my name on them. Nothing’s really a mystery now, but back then you could do a mystery LP and there were distributors that would distribute it. Then it would be written about in ’zines and no one really knew who it was.”

After a few releases, Chasny settled on the Six Organs moniker. It became the banner under which he cultivated new styles of haunting experimental music using dark harmonies and drones as well as atmospheric synth and vocal sounds. As he fearlessly shaped his rock and punk background into a captivating form, his acoustic playing, specifically, found an audience among the biggest names in stoner, doom, and black metal. Improbably, he was soon sharing bills, tours, and festivals with artists such as Om (with whom he released a split 7"), Wino from the Obsessed, and Neurosis.

“It’s funny, because everyone wants me to play acoustic guitar,” he says. “The heavier dudes seem to prefer it. It’s like, ‘No, no. We’ll do the heavy stuff, kid. You play the acoustic guitar or something.’”

“My favorite guitar players are the ones who are, as they say, in the service of the song: guys like Richard Thompson or Lindsey Buckingham.”

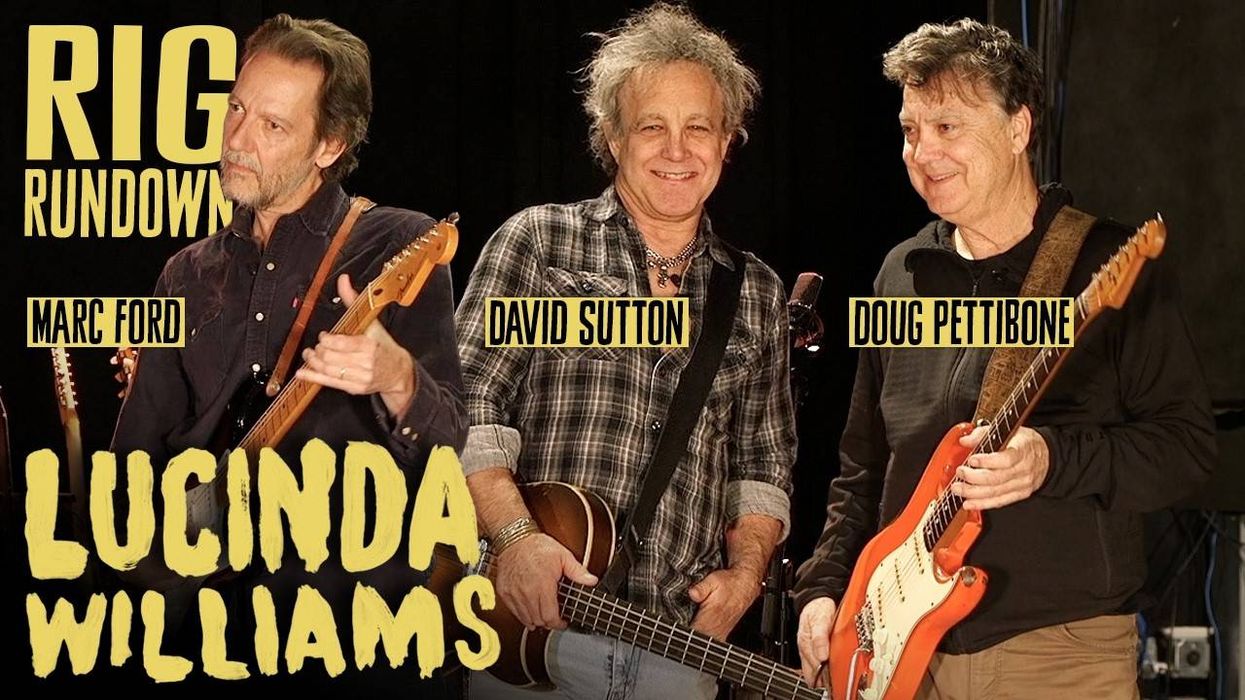

Even within such an unpredictable career, Chasny’s latest veers like a left turn into outer space. The Intimate Landscape was initiated when KPM Music—a production music business with a large catalog that specializes in commercial placements—reached out with an invitation to create a set of library music. The only catch, he says, was that, like the metal guys, KPM wanted his acoustic side.

“I had visions of doing a soundtrack, some weird, horror, Blade Runner record. But they said, ‘No, no. We want acoustic guitar,’ which was a little disappointing. But I said, ‘Okay. I can do that.’”

Wary of simply knocking out a handful of jingles, Chasny decided to create an artistic album—which would also be released by the Drag City label—that suits commercial use. “When I hear music that could be used for a fishing show or something, I don’t think that it’s an artist putting everything into it,” he explains. “One of my ideas was to try to record nice music, not production music. Even though that’s what it would be used for.”

Deep into a career in underground music, not only did Ben Chasny accept an invitation to create a set of fingerstyle-guitar library tunes for commercial placement, but he’s made it his first album under his own name.

Conceptually, this runs counter to what Chasny has done across his Six Organs discography. “I’ll do acoustic that’s often smeared with dissonance, or noise, or something,” he explains. “This was my chance to not do that. But I had to fight against my instinct to subvert the melodies. It’s a challenge to make music that is a little more pretty. I want to start doing music under my name that will be a little more on this side of things. And I’m hoping to steer Six Organs into more of the experimental side. It’ll be easier for people to know, ‘This one’s going to be a little more mellow, and this one’s going to be a little tougher to listen to.’”

If words like “pretty” make it sound like Chasny has sold out, don’t worry. He was free to pursue his own vision. “I didn’t know what to expect, but I didn’t know I was going to have so much freedom,” he says. “I gave them a little sample and said, ‘This is what it would sound like.’ They said, ‘That’s great. Make a record like that.’ And it was cool because I was working for somebody else, in a way. I knew exactly what I needed to do instead of sitting around wondering.”

“I had to fight against my instinct to subvert those melodies. It’s a challenge to make music that was a little more pretty.”

The result is focused and warmly listenable. Every piece on The Intimate Landscape puts Chasny’s guitar melodies front and center, while his touch and tone fill out his sonic vision. On “Cross-Winged Formation,” the intimate sound pulls you in. It’s as if you can hear the guitarist’s fingerprints on the strings. And just when you’re lulled into the moment, the song’s chorus expands with a low-string melody and open-string ornamentation.

Then there’s “Water Dragon,” a minor-key dirge that blends classical picking technique with an ominous vocal backing. It’s the one song that bridges the gap between his past and present work. “‘Water Dragon’ is a little nod to Six Organs,” he admits. “It has that more modal playing and the vocal drone. I did want to have a little window to something that ties it to previous records.”

Ben Chasny's Gear

Chasny still plugs in but says his acoustic playing has developed a reputation among metal audiences and commercial music houses alike. “Everyone wants me to play acoustic guitar,” he says!

Photo by Tim Bugbee

Guitars

- Alvarez Yairi Bob Weir model

- Martin 00C-16DBGTE (with LR Baggs Anthem pickup system)

Strings

- D’Addario .010 sets

While mainly a new direction, this album doesn’t sound like someone stretching for something new. It sounds more like an artist drawing on familiar influences to paint a new picture. But Chasny did mine one influence that, until now, he’s kept close to the chest.

“There’s this one record that I absolutely love that I never hear any acoustic players talk about, and that’s A Shout Toward Noon by Leo Kottke,” he reveals. “I love that nobody talks about that record, and I’ve never talked about it. I always try to keep it a secret because that’s the one that always inspires me for melody. The melodies on that record floor me.”

In addition to Kottke’s influence, we hear Chasny’s consistent fingerpicking technique and how he pushes and pulls time to suit the moment. And we know how much work it takes to get there. “I practiced a lot when I was younger,” Chasny says. “It was serious. I had very part-time jobs, and I practiced guitar for a long time. I’d try to learn as much as I could. I don’t really practice acoustic guitar. So, the actual technique stuff maybe comes from playing electric guitar. That gets ported to the acoustic a little bit, like some fretboard, left-hand stuff.”

“One of my ideas was to try to record nice music, not production music. Even though that’s what it would be used for."

His electric playing had an influence on Chasny’s choice of acoustic instrument, which for about a decade or so was his trusty, highly playable Alvarez Yairi Bob Weir model. “I love it because of the neck,” he says. “It’s easy to go from electric to acoustic because it’s really fast, like a shredder neck or something. I fell in love with that before the tone. I used to have some ‘real tone’ friends that would give me shit about it. But I really liked that guitar a lot.”

Unfortunately, the decade did a number on that guitar, and it started showing its age, so Chasny has moved onto a Martin 00C-16DBGTE that he says is “not that much different than the Alvarez.” That guitar had a rough start, developing cracks after one tour, but it’s now become his go-to acoustic. Paired with a set of dead, bronze guitar strings, it’s the sound of The Intimate Landscape. “It was only that Martin on this record. I think I changed the preamp plug-in for a song. The rest of it was one preamp emulation and that guitar.”

Much of The Intimate Landscape’s charm is in the immediacy of Chasny’s simple, DIY production and arrangements. From “The Many Faces of Stone” to “On the Way To the Coast,” it’s as if you’re sitting in front of the guitar’s soundhole. Though KPM offered to send him to a professional studio, he chose to keep things as straightforward as possible. “I did it by myself, at home, with my gear. And it’s all mono,” he points out. “The stereo is from the reverb, but I didn’t do any stereo recordings. I start getting freaked out about phase cancellation. Then I start wondering, ‘Can I even hear phase cancellation? What am I doing? Maybe I need to go to a studio?’”

TIDBIT: KPM Music offered to send Chasny into a professional studio, but he opted to record at home and kept his variables simple, using just one mic and one guitar.

Resisting the urge, Chasny pushed himself to get the most from a single, affordable microphone in an untreated room. “It was recorded with this really cheap mic called a CM3,” he says. “It’s a little pencil condenser made by Line Audio. It was one of those things where you go on the forums and look for ‘the best mic for acoustic guitar’ and everyone’s arguing. Five pages later, I found out about it.

“I angle it down a little bit, and it’s pretty close. I like close-miking at home because my rooms are not treated very well. Which is another reason why I don’t do any ambient mics.” Once it hits his DAW, he continues to keep it simple. “I do EQ, but I don’t do compression with fingerstyle. I leave that to the mastering person if they want. I just smack some reverb on it.”

Chasny prefers to stay rhythmically unencumbered when recording solo playing. “None of this record was done with a metronome. It’s all free time,” he says. “I think it might set it apart from other production music a bit.” This allows Chasny to manipulate the feel of each section on the fly. A case in point is “Second Moon.” Listen as he pushes and pulls the time, matching the emotional flow of each song.

“When I heard the first few chords on [Nick Drake’s] Five Leaves Left, it blew my mind."

This level of control only comes through practice and commitment to craft and genre. Yet Chasny avoids labelling himself a fingerstyle guitarist. He’s more inspired by players who put the music before the playing. “I’ve got a few tricks and I probably could learn some more,” he says. “But my favorite guitar players are the ones who are, as they say, in the service of the song: guys like Richard Thompson or Lindsey Buckingham.”

If it sounds like Chasny has abandoned his electric side, fear not. While he already has plans to record another acoustic set for KPM, he’s also conjuring a cranked-up vision for the next Six Organs album. “It’s definitely going to be electric, and I’ve got some ideas about it.”

Explaining Ben Chasny as an artist isn’t going to get easier any time soon. His music is all over the place, and he purposefully avoids classification. But there is a common thread that ties his entire career together. Look too hard and you might miss it, but it’s always there.

“This sounds cheesy as fuck, but I really love guitar,” Chasny says. “I remember when I was young, playing one note. It was so exciting. It was so fucking good. I still have that every once in a while. Maybe that’s why the varied stuff. I love absolute noise guitar, but I also like Paul Gilbert! I don’t know why I love guitar so much. I ask myself that all that time. I don’t know what it is, but I love guitar.”

Six Organs of Admittance - Shelter From the Ash

Get a feel for Chasny’s dark and droney fingerstyle sound in this intimate living room performance of the title track from the 2007 Six Organs of Admittance album, Shelter from the Ash.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)