Amid the San Francisco Bay Area’s dense fog, the Golden Gate Bridge stands as a de facto lighthouse, guiding those navigating the land and sea. In many ways, blues guitarist Joe Louis Walker embodies the essence of this Californian landmark. For over half a century in his professional musical career, Walker has been a beacon of inspiration, a potent conduit—sometimes navigating over choppy waters, but always bridging traditional blues with waves of soul, rock, and gospel.

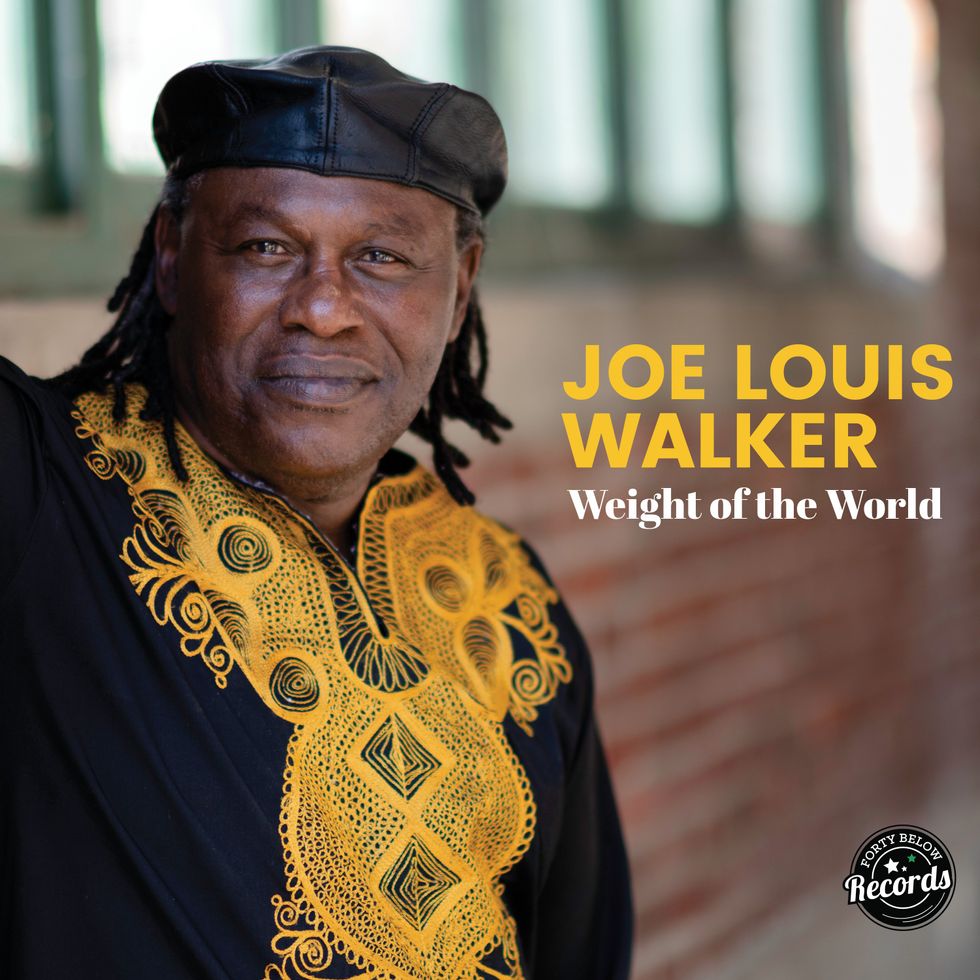

Walker’s latest album, Weight of the World, is utterly vibrant. On “Hello, it’s the Blues,” he inquires, “What’s the blues?” Over the phone, Walker takes a poetic slant in answering the question. “One of the perfect phrases for me is what Shakespeare called the human condition,” he says. “If you have the human condition, you can be on top of the world material-wise and have the worst personal life in the world. What’s the blues? It’s just your good friend.”

Produced by Eric Corne, who has also recorded Glen Campbell and Lucinda Williams, Weight of the World displays a rich mix of musical styles, guided by Walker’s powerful vocal and guitar work, and replete with horns, strings, organ, and harmonica. The album breathes with the soul of a veteran player that has spent decades learning how to capture the spirit of blues, but in a way that substitutes its traditional voice of wicked tragedy with that of funk, gospel, and celebration. “You Got Me Whipped” swings with a smooth-as-silk guitar tone, while the lively “Waking Up the Dead” parades down Bourbon Street. “You can’t lose with that second line drumbeat,” Walker says. For “Hello, it’s the Blues,” he brings in a nylon-string acoustic. “You don’t hear nylon-string acoustic in the blues,” he remarks. “I’m playing classical scales. You hear the 12-bar, but when it goes to the B section, it changes. I like guitar players who can do that. God rest his soul—Jeff Beck did that all the time. He could go one way with a song and then really take it another. It’s an emotional song. I’ve got to bring emotion.”

Joe Louis Walker - The Weight of the World

For Walker, that emotion has been cultivated from the time he was born in 1949, on Christmas Day, to musical parents. His father was from Mississippi, and his mother, Arkansas, but the family settled in the eclectic Bay Area. As a young boy, his father’s Delta blues collection captured his attention, as did his mother's affinity for B.B. King. Walker first explored the violin before settling on the guitar when he was 9 years old.

San Francisco’s Fillmore District provided a hotbed of culture for the young Walker. Between guitar lessons, he played music with his cousins, but he also studied the masters of blues, from King and T-Bone Walker to Otis Redding and Meade Lux Lewis.

“You can be on top of the world material-wise and have the worst personal life in the world. What’s the blues? It’s just your good friend.”

By the time he was 14, Walker was a union-card-carrying working musician, finding early work writing jingles for Sly Stone’s radio program in San Francisco. The original Fillmore Auditorium was an essential part of his development. “When I was 14 years old, I took my grandma to see Little Richard at the Fillmore, when he got religion for a little while,” Walker remembers. “After that, the Fillmore Auditorium was like our community playhouse. It was only a half block from our school, and we had our battle of the bands there and played all kinds of music. Then, I was in a family band with my older cousins, and played all over.”

Walker admits the lifestyle he walked into isn’t for the faint of heart. “It’s something you have to have a constitution for,” he says. “I've spent years, years, in dark rooms, nightclubs, playing. It was normal for me to sleep until 12 in the afternoon [laughs], and then get up and go play.” By the time he was 16, he had moved out of his parents house to play professionally. His fate was sealed.

On Weight of the World, Walker showcases his veteran skills at blending blues, rock, soul, funk, and gospel.

Walker was an ambitious teen. He built street cred working in house bands along the Fillmore District and the wider Bay Area. Back then, he gigged at Eli’s Mile High Club in Oakland where he shared the stage with Stone, and both John Lee and Earl Hooker. Of all his stomping grounds, Walker recalls the legendary club the Matrix with particular fondness.

“I backed up a lot of older blues players, traditional guys,” he says. “I was partial to Mississippi Fred McDowell. He took a minute out with me when I was 16 and let me play with him at the Matrix. He was a country gentleman, and he told me some things about people in general. ‘Surround yourself with good people,’ and things of that nature. When I didn’t do everything he said, it seemed like it came true.”

“It’s something you have to have a constitution for. I’ve spent years, years, in dark rooms, nightclubs, playing.”

But then, San Francisco’s explosive Summer of Love in 1967 changed the city’s music scene forever. Walker remembers: “The young guys and older musicians could play seven nights a week, up and down Fillmore all the way to Haight. You could play jazz, blues, whatever you wanted—before Bill Graham and the hippies came to our neighborhood. For us young guys who had been there all the time, we’d see the Temptations. We would see Ike and Tina Turner when they never even thought about rolling on a river. It was exciting, and then it flipped on its head. Guys who had been playing the Fillmore all the time now couldn’t get a gig there.”

In 1968, Walker began a friendship that would follow him for the rest of his life. He met Michael Bloomfield of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band by chance at a bookstore the day after witnessing Bloomfield’s jaw-dropping set at the Fillmore. Bloomfield, says Walker, was one of the hottest young upstarts in Chicago blues music, thanks in part to going to “the well” to learn to play, consulting the greats. After Bloomfield quit the Butterfield Blues Band and Walker started his own band, the two became roommates. “He was a taskmaster,” says Walker. “He’d come in and give me a critique after shows. One time, he goes, ‘Man, it’s a good thing you can sing because you ain’t playing shit.’ And I wasn’t. I was just a young guy trying to copy all the different guitar styles that I heard. It was just mumbo jumbo. But that’s your growing pains.”

Walker says Bloomfield looked out for him in the early days. As time went on, Walker returned the favor. “Michael gave me guitars, a place to live, got me gigs and auditions,” says Walker. “I could never, ever in this world repay him. I did look out for him as far as driving him places because he wasn’t such a great driver, and [I was] keeping an eye out for him, getting the guitar for him. He had a ’59 Les Paul, and I’d put it in the back of the car because he had left it with no case or anything.”

Joe Louis Walker's Gear

Over 50 years, Walker has put out more than 30 records and guested on scores more. He played on B.B. King’s Grammy-winning 1994 record, Blues Summit.

Photo by Joseph Rosen

Guitars

- Zemaitis Pearl Front

- Zemaitis Metal Front “ZV”

- Zemaitis Greco BGW22

- Zemaitis acoustic with heart-shaped soundhole

- Spanish nylon-string guitar

Amps

- DV MARK Multiamp FG Frank Gambale Signature Guitar Head

- RedPlate Amp 2x12 with Dumble-style head and 2x10 cabinet

Effects

- Way Huge Smalls Aqua-Puss Analog Delay

- Dunlop MXR MC401 Boost

- Crybaby Q Mini 535Q Auto-Return Wah

- Dunlop Jimi Hendrix phaser

Strings, Picks, and Slides

- Dunlop (.010–.042)

- Dunlop medium picks

- Dunlop medium glass slides, metal slides, and brass slides for electric

Around the mid-1970s, Walker was evaluating his surroundings. When he took a break from music to take stock, he was shaken. “I saw that so many people, people that I had been fortunate enough to meet through Michael and Buddy Miles and others, were dying,” he says.

Sadly, in 1981, Bloomfield joined their ranks when the guitarist died from a drug overdose at age 37. Walker thoughtfully remembers his friend: “He was all about going from your heart to your head to your hands,” he says. “I switched my game totally, and if I hadn’t, I would be dead like a lot of those people. [Before he died,] Michael turned into a recluse. And a lot of other people, if they made it through the other side, they’re all now legends, but they went through some serious changes.”

After Bloomfield’s death, Walker turned to gospel music. He joined the Spiritual Corinthians Gospel Quartet, and connected with the material’s depth of feeling. “I tapped into that feeling when you’re singing,” says Walker. “It’s like when a blind person sings and plays. When you see Stevie Wonder or Ray Charles, they go to another place. You can physically see it. They’re creating an emotion that nothing can stop. I think when you have that kind of channeling, that’s what any artist wants to do—is just have it flow.”

By the mid ’80s, Walker was beginning to circle back to blues music. He had a particular moment of clarity while playing the gospel tent at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival in 1985. “I just said, ‘you know what? I’m a restless soul with music,’” he recalls. “Anybody listening to the 30-plus albums I’ve got, they’ll hear me doing all kinds of stuff. It was just a sign of things to come for me.”

“When you see Stevie Wonder or Ray Charles, they go to another place. You can physically see it. They're creating an emotion that nothing can stop.”

Back in San Francisco, he formed a new backing band called the Bosstalkers, and signed with HighTone Records. While young blues cats like Robert Cray and Stevie Ray Vaughan were hitting the mainstream, Walker was staking out his own territory, releasing his debut, Cold Is the Night, in 1986 to critical acclaim.

Two years later, Walker was on the road touring with his idol, B.B. King. King had some sage words for his junior. “[He] told me, ‘I know your friends Robert Cray and Stevie Ray and all the younger people are making it, and you quit playing blues and all that, and now you’re playing again, but you’re going to have a long career,’” says Walker. Aside from a working relationship, King and Walker became friends.

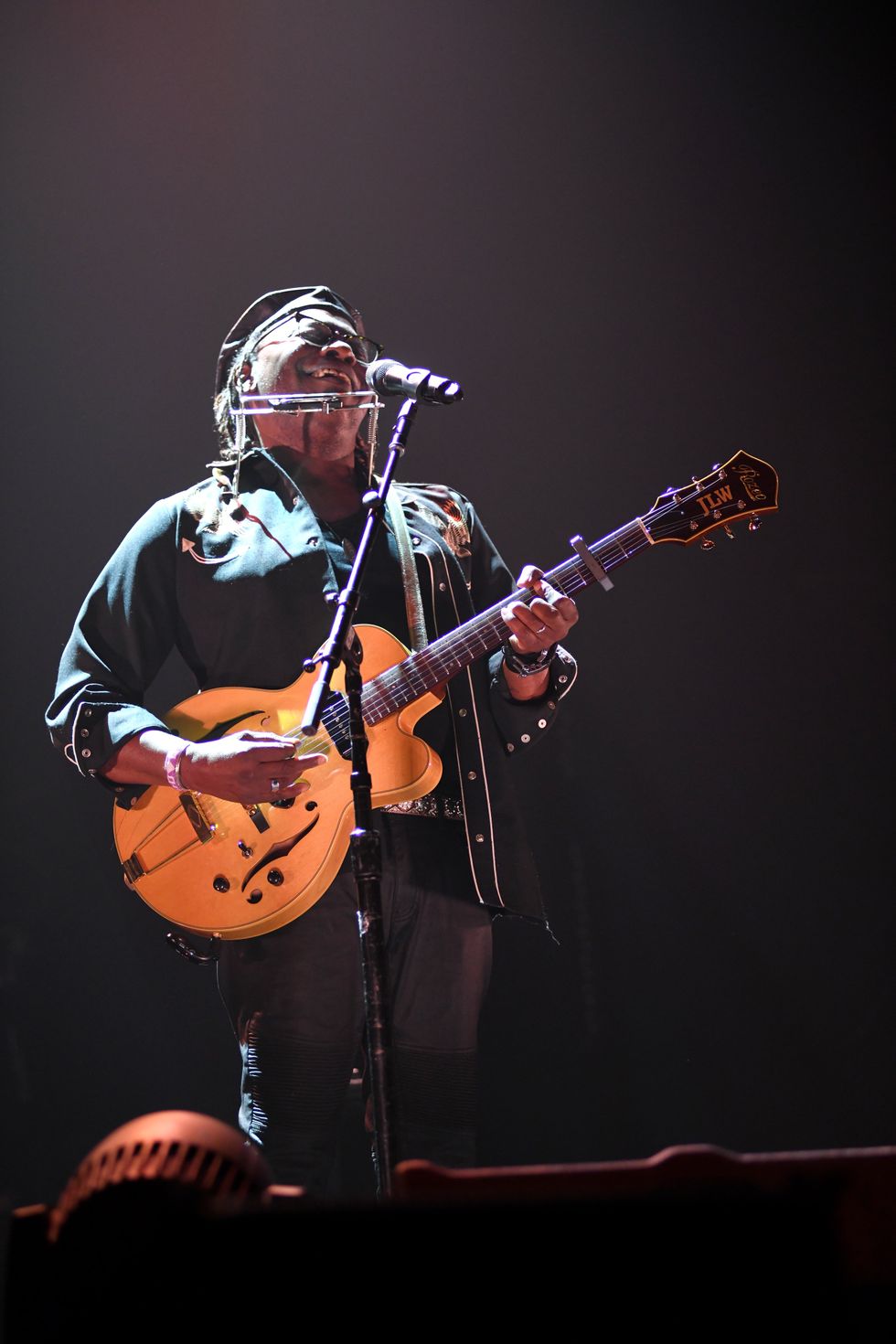

Here, Walker wields his pearl-front Zemaitis guitar, but lately his Zemaitis Flying V has been his go-to.

Photo by Mickey Deneher

Walker followed his HighTone debut with 1988’s The Gift, his second of seven records with the label. “I’ve been fortunate as an artist,” he says. “I’ve never had a record label say, ‘You can't do this, you can’t do that.’” Beginning in 1993, Walker released a string of records with Polydor/PolyGram, all of which deepened and demonstrated his smokin’ guitar skills. Another major milestone arrived that same year: Walker shared duet responsibilities with B.B. King on the legend’s Grammy Award-winning Blues Summit album.

Walker’s 1997 album Great Guitars, produced by Steve Cropper, boasted a top-class cast of guest stars, including Buddy Guy, Taj Mahal, Ike Turner, and Bonnie Raitt. Walker tapped Raitt for the song “Low Down Dirty Blues,” which features male and female characters in a vocal back-and-forth. But there was a hitch. “Bonnie said, ‘Look Joe, I can do anything, but the record company doesn’t want me to sing on anybody’s stuff,’” remembers Walker. Later, Raitt heard Walker singing both his part and hers, and Cropper quipped about Raitt’s absence. She stormed out of the room—and returned a second later. “She says, ‘Fuck the record company. Give me a microphone,’” Walker laughs. “That’s the redhead I love.” The result is sheer blues excellence.

“Muddy would tell me to slow down. ‘Slow it down, because slide is not like playing regular guitar.’”

Through the 2000s, Walker collaborated with dozens of musicians and consistently released albums, touring behind them and making regular pilgrimages to popular blues festivals around the world. His albums Hellfire and Hornet’s Nest, produced by Tom Hambridge, explored stinging blues-rock and busted more genres. Walker was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2013, and netted a Grammy nod for his 2015 record Everybody Wants a Piece.

But he’s never lost his taste for blues building blocks. Journey To The Heart Of The Blues was an all-acoustic offering, just Walker and a piano, released in 2018. “I like variety, and I like to push myself,” he says. Always in demand for others’ projects, Walker played on Dion DiMucci’s Blues With Friends in 2020, and contributed music to the PBS documentary Driving While Black.

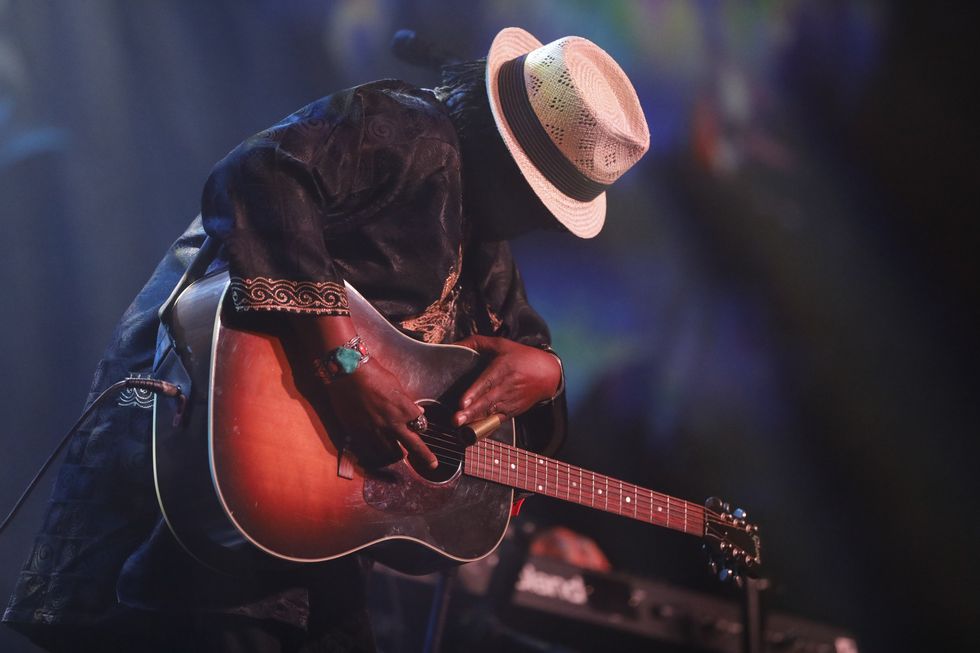

Joe Louis Walker came up playing the blues in San Francisco, but 1967’s Summer of Love shuffled the music out of the spotlight.

Photo by Frank White

Over a 50-year career, Walker has experienced soaring highs, but his most treasured are also the earliest: those times when he got to consult with his blues torchbearers, and play with the likes of Willie Dixon and Ronnie Wood. These teachers taught him lessons that he still holds dear. “I was fortunate to play with Fred McDowell, an old-school guy who played an acoustic by himself,” says Walker. “I played with Fred, and I lived with Bloomfield, who knew a lot about slide, and a lot about American music, period. He showed me some different tunings.”

A particular note from Muddy Waters sticks out in his mind, too. “Muddy would tell me to slow down. ‘Slow it down, because slide is not like playing regular guitar. You can just cancel the notes out if you play it too fast,’” recalls Walker. “Muddy was a master at slow blues. I mean, really slow. You can hear every word, every note, and every emotion that he wanted you to feel in a song.”

Ultimately, Walker wants to deliver emotionally fueled songs that take listeners to different places. “Some styles of music don’t modulate, switch keys, or use minor keys,” he says. “The keys are like colors. If you play a song in a certain key, it’s a color that draws a certain emotion. I like movement in music.”

YouTube It

With bends, slides, and warm yet hearty vocals, Walker performs this 2022 show at the Scranton Cultural Center with the same band featured on Weight of the World.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)