On the Melvins’ new record, Tarantula Heart, the first track alone is longer than most hardcore punk records. “Pain Equals Funny” builds, collapses, and rebuilds over nearly 20 minutes. It’s grungy and bizarre and confrontational, swerving across prog-metal, industrial, noise, and grease-smeared stoner rock. Buzz Osborne’s trademark foghorn voice, sounding out from between his mad-scientist hair and high-priest robes, blasts in and out of the track with contextless proclamations and anecdotes, his behemoth guitar thrashing across an ocean of distortion. Steven Shane McDonald’s bass drones, flooding the room; Dale Crover’s drums, often doubled and bolstered by Ministry drummer Roy Mayorga’s, are punishing, bare-knuckled and relentless. Feedback interrupts in squeals, then in squalls, until it’s all you can hear—then, it’s instruments that disrupt the feedback, rather than the other way around. The track stews and clangs and hulks along without any indication of where it’s heading next. It’s the sound of chaos distilled and reined in, just barely. It sounds a bit like life.

Melvins "Working The Ditch"

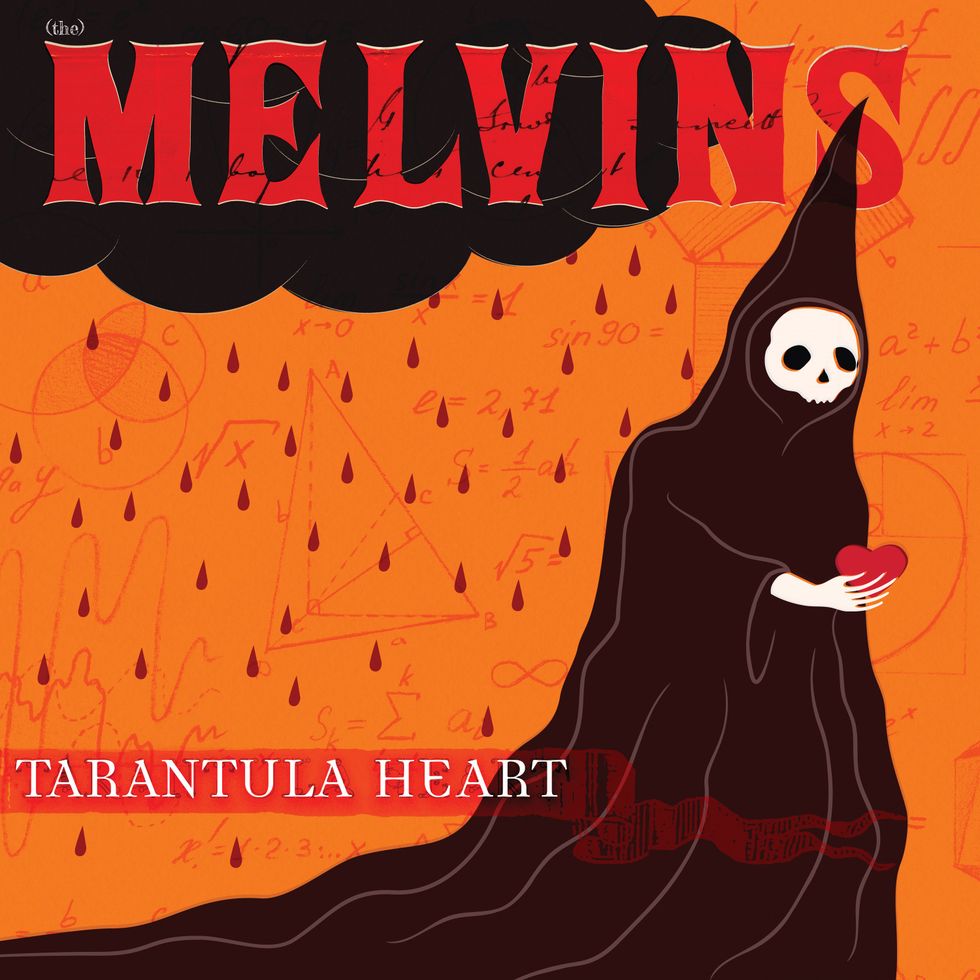

Tarantula Heart is the veteran avant sludge-metal band’s 27th full-length record since their debut LP in 1987, and their 18th with label Ipecac Recordings. They obviously practice a sort of creation that is at odds with the traditional contemporary studio and band business model. Some people might just call it flat-out weird. It’s not uncommon for bands to go three to five years without new material and milk each album cycle for a couple more. So, why produce and release so much music if you don’t have to? Maybe the more interesting question to answer is: If you care about making music, why wouldn’t you?

“It’s a really weird record,” says Osborne. “I wasn’t sure what Ipecac would think. We turned it in, and they were like, ‘This might be our favorite one you’ve ever done.’

“We’ve done almost 30 albums, depending on what you count as an album, and at this point, the idea of doing things like I’ve always done, it doesn’t really excite me too much. I’m always looking for something new, some new idea: see if we can do this, see if we can pull that off. There’s enough bands out there doing traditional music. People shouldn’t expect us to.”

McDonald—who’s been with the band since 2015 and is also a member of punk icons Redd Kross—puts it simply: “It was the Melvins yet again finding a different way to skin a cat.”

“We’ve done almost 30 albums, depending on what you count as an album, and at this point, the idea of doing things like I’ve always done, it doesn’t really excite me too much.” —Buzz Osborne

By the band’s count, Tarantula Heart is their 27th LP of original material in their long and storied career.

If Tarantula Heart sounds at times like listening to a group of musicians simply bashing out ginormous riffs and exploring how far they can push things in a jam space, well, that’s pretty spot-on. The record was created primarily over two days of jamming with both Crover and Mayorga on their own kits at Melvins’ rehearsal space in an industrial area in the San Fernando Valley, which they share with long-time producer Toshi Kasai. Melvins have a history of playing with two drummers at the same time. For nearly a decade starting in 2006, Crover and Coady Willis both thundered along behind the band. “It’s like you’re riding this gigantic beast,” says McDonald of playing with two drummers. “It’s like an earthquake.”

The jams were unstructured and random, but afterward, Osborne took the audio files home and combed them for ideas. He’d find five- to seven-minute sections that stuck out, then isolate the drums and write new riffs, solos, and melodies overtop of them. Good friend and WE Are the Asteroid guitarist Gary Chester swung by to help fill out the chaos, and Osborne and Kasai traded off roles as either string-strummer or pedal and amp knob-turner to create “white noise insanity.” “I know I’m onto something in the studio when you’re not playing the guitar but there’s so much amp noise that it sounds like a vacuum cleaner,” says Osborne. Later, he stitched the ideas together to create the Frankenstein monsters on Tarantula Heart. By the time Mayorga and Crover heard them, they were entirely different songs.

“It’s like you’re riding this gigantic beast. It’s like an earthquake.” —Steven Shane McDonald

That process would be off-putting for many musicians, but Melvins aren’t terribly serious in the studio, says Osborne. He dislikes the self-importance that the environment can promote in musicians. “I feel privileged to be in a situation where I can do this for my living,” he says. “I don’t lose that perspective on it but like, I want to have fun, and I’m really happy I’m here.”

Part of the method behind Osborne’s madness is that he believes musicians will perform more purely, more excitingly, if they don’t have to adhere to any framework. “If you let people own the songs in some way, you’ll get a better performance out of them,” says Osborne. That’s a philosophy he picked up from David Bowie. Osborne claims that when Bowie handed guitarist Adrian Belew a tape of songs to learn, he told him, “Play them like this or better.”

Most of the material on Tarantula Heart came from open-ended jams at the Melvins’ rehearsal studio, with Ministry drummer Roy Mayorga doubling Dale Crover’s thunder.

Photo by Tim Bugbee

And for Melvins, that ethos doesn’t end when the song is finished. Osborne believes that songs aren’t just allowed to change after they’re recorded, but that it’s necessary for them to do so. When Osborne was a kid, his favorite band was the Who, and when he heard their 1970 live record, Live at Leeds, he was thrilled by how different the songs sounded. Bowie’s adventurous live recordings, too, were instructive. “I learned that lesson really early on, even before I played guitar,” he says. “The live experience is something different. If you go by the record, we’re playing [our songs] all wrong. Things grow. I’m not married to any kind of conventional thing when it comes to how we play live or anything like that.

“The idea that we would want to translate perfectly and exactly how we do it on a record is completely absurd to me. I’ve heard bands say, ‘Well, how are we going to pull that off live?’ Don’t worry about it. Change it. Who cares?”

“I know I’m onto something in the studio when you’re not playing the guitar but there’s so much amp noise that it sounds like a vacuum cleaner.” —Buzz Osborne

Osborne’s unshakeable approach feels like a threat to a modern music industry that, under the boot of a ruthless market, balks at risk and favors a sure thing. And while the Melvins have built a successful, long-lasting career doing their thing, they’ve also watched their peers rocket past them into the mainstream. Crover played drums with Nirvana while they were recording the songs that turned into their debut LP, Bleach, and Osborne was friends with Kurt Cobain, introducing him and bassist Krist Novoselic to Dave Grohl. Like Nirvana, Melvins signed to a major—Atlantic Records—and seemed poised to join their grunge and punk pals atop the charts. But after four years and three records (plus one farther afield release, Prick, which the band released under the name ƧИIV⅃ƎM, allegedly to avoid breaking their contract with Atlantic) the label dropped the band.

The fact of their trajectory versus Soundgarden’s or Nirvana’s is more a curiosity to Osborne than anything else. “We were much weirder than those bands that commercialized it in a way that we never did or never could have,” he says. “You just carve out a spot with all that in mind. The funny thing about all that was that I was making a living playing music before those bands ever got big. It was already working on a smaller scale.”

Buzz Osborne's Gear

The Melvins came up in the same scene as grunge legends Nirvana and Soundgarden, bands that Osborne says were “smarter” in figuring out how to commercialize gnarly sounds.

Photo by Joshua Jennings

Guitars

- Electrical Guitar Company King Buzzo Standard

- Electrical Guitar Company King Buzzo Signature

- Electrical Guitar Company Wedge

- Gibson Firebird

- Gibson Flying V

- Gibson 50th Anniversary Pete Townshend SG

Amps

- Hilbish Design Preamplifier

- Tyrant Tone 2x15

- Tyrant Tone 2x12

Effects

- Hilbish Design Pessimiser

- Hilbish Design Compressimiser

- Hilbish Design Deathimizer

- Dunlop Cry Baby

- MXR Blue Box

Strings and Picks

- Ernie Ball Skinny Top Heavy Bottom

- Tortex Triangle Pick .50mm

Over their years on the road, Osborne has converted McDonald to his strategy of only carrying gear that can be replaced at a moment’s notice from any generic music store. It’s largely the result of brutal mishaps—McDonald guesses that around four of Osborne’s vintage Les Pauls have had their headstocks broken by various airport authorities and baggage handlers. Any TSA agent can open your guitar case upside down, McDonald notes, but he also appreciates the reality check of the approach. “If you get hooked on something that seems like it has that invisible secret mojo, then it’s hard when that object lets you down and you feel like you can’t replace it easily,” he says. Now, McDonald tours with an Epiphone Thunderbird 60s bass that he bought off of Amazon. “If worse came to worst and I needed another one of those on the road, I could have one shipped to the next Holiday Inn Express,” he says.

“I’ve heard bands say, ‘Well, how are we going to pull that off live?’ Don’t worry about it. Change it. Who cares?” —Buzz Osborne

Osborne will still bring new Electrical Guitar Company instruments on the road, probably because they’re virtually indestructible. Built in Irondale, Alabama, they borrow from (and in some cases replicate) the Travis Bean-style aluminum builds which have long been favored by offbeat noise-makers. Osborne counts a couple signature models with EGC—a fitting collaboration for one of guitar music’s freest spirits.

Osborne says people still approach him to praise what they believe to be a tone summoned by a Les Paul ripping through a Marshall, a combination that these days prompts Osborne to recoil: “God, wake me up later,” he groans. These days, he’s pretty sure of what he doesn’t want in his sound. But what he does want can be trickier. That can change from night to night, hour to hour.

“I’m one of the weirdos that likes brand new stuff,” says Osborne. “I don’t know. It’s fun to keep moving forward.”

Steven Shane McDonald's Gear

On the road, Osborne and McDonald stick to either new, easy-to-replace gear, or bomb-proof kit like the aluminum and plexiglass guitars from Electrical Guitar Company.

Photo by Chris Casella

Guitars

- Epiphone Thunderbird 60s bass

Amps

- Darkglass Electronics Microtubes X 900

- 8x10 cabinet

Effects

- Boss PH-3 Phase Shifter

- Electro-Harmonix Pitch Fork

- EarthQuaker Devices Hizumitas

Strings and Picks

- Ernie Ball Regular Slinky Bass (.050-.105)

- Tortex Sharp Pick .88mm

YouTube It

Melvins are just as weird and heavy as they were 40 years ago, as this 2023 live set at Germany’s Freak Valley Festival demonstrates.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)