The Melvins are not a joke. Don’t be fooled by frontman/guitarist Roger “Buzz” Osborne’s graying Sideshow Bob hairdo. Don’t dismiss the quirkiness of originals with titles like “Sky Pup” and “Rat Faced Granny,” or their haunting cover of Paul McCartney’s “Let Me Roll It” from last year’s Freak Puke, or the new Melvin-ized version of the traditional tune “You’re in the Army Now” off their brand-new album, Tres Cabrones. But if you do happen to laugh at the 30-year doom-grunge vets, just know they’re laughing, too.

“Sure, we want to be funny, but those songs are still very meticulously done when we’re recording them,” says Osborne. “It works because it’s good—it’s not just some joke. It has a melody, it’s well crafted, and they’re catchy as hell.” Therein lies the success of the Melvins—they’ve got the ying of Sabbath-style, oozing-tar riffs mixed with the yang of melodiously delivered, tongue-in-cheek lyrics and wonky song titles.

While they’ve never been known to dwell in the past, for Tres Cabrones—their 19th studio album—the Melvins opted to reconnect with original drummer Mike Dillard. “I’ve known Mike since probably 8th or 9th grade—we were partners in crime well before music,” says Osborne. “Now he’s an all-American guy with a union job, a wife, and kids, so I was just happy to get Mike on a real Melvins album. He’s a great guy, a solid drummer, and I’m happy that he can tell his kids when they’re old enough that their dad was a rock drummer.”

With Dillard sitting in on drums, longtime drummer Dale Crover moved to bass, and the change effected something of a nostalgic trip back to the group’s more simplistic hardcore origins. “It was fun because we played to our strengths with this lineup and we ended up making an album that sounds like a throwback to our early material,” says Osborne.

Osborne says the approach resulted in simpler, more digestible songs that sound like they’ve been excavated from the band’s late-’80s or early-’90s canon. To break up some of the heaviness, they also got their funny bones working on traditional covers of “Tie My Pecker to a Tree” and “99 Beers.”

“We worked as hard on “Tie My Pecker to a Tree” and “99 Beers” as we did anything on Tres Cabrones, but we were laughing our asses off while doing it—we had to redo takes because you could hear us in the background,” he says. “I think music has made us nuts.”

We recently spoke to Osborne about the making of Tres Cabrones, as well as all the crap he takes for his vibrato technique and why he opts for mainstream stompboxes. And don’t miss our interview with Crover (page 3) about relinquishing the drum chair and taking on bass duties for the new album.

Mike Dillard hasn’t been in the band since the early ’80s. What led to him joining you for Tres Cabrones?

A few years back we put out some original demos on [former Dead Kennedys frontman] Jello Biafra’s label, Alternative Tentacles. He had a 50th birthday party in San Francisco and he asked if the Melvins would play. Dale mentioned that we should have the original lineup—or close to it—play the show, since the demos they released were from that iteration of the group.

How did you parlay that performance into an album?

Well, before the gig we got Mike down from Washington and we recorded some of our rehearsals—and we sounded really good. We talked out loud how cool it would be to record new songs to perform as this de facto original lineup. All of us were onboard immediately. Obviously, Mike’s a very busy guy with a limited amount of vacation time, so it required some planning to make sure every time he would come down here to record we had material and ideas to work through.

Aside from flying Mike down for recording, how were these sessions different from previous Melvins sessions?

What you have to understand is that we do a lot of bulk recording. During our last recording cycle, on one day we’d do vocals for a [alternative band lineup] Melvins Lite song, bass parts for our Everybody Loves Sausages cover album, guitar overdubs for Tres Cabrones, and a solo for a song on Freak Puke.

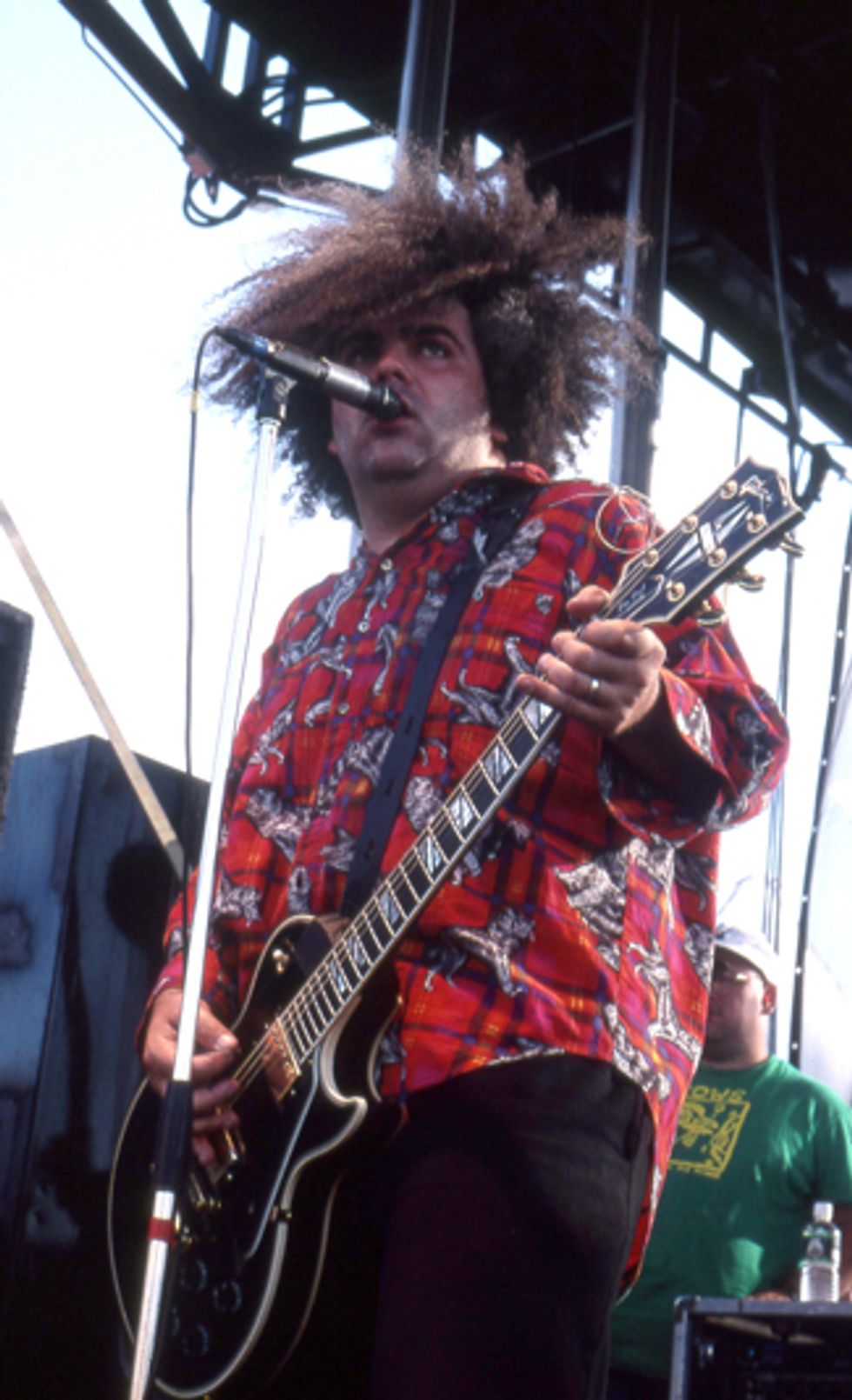

Melvins' frontman/guitarist Roger "Buzz" Osbourne "ham-fisting" his Les Paul Custom during the band's set on the second stage at Ozzfest in 1998 at the Blockbuster Center in Camden, New Jersey. Photo by Frank White

Isn’t it kind of mind-boggling to work

that way?

Once you get the ball rolling, it’s easier to do more extra material than break everything down and start over again in a few weeks or months. I feel that creativity welcomes inspiration. We shouldn’t limit ourselves to working on Tres Cabrones. Like, if a song doesn’t fit in that format, we’re going to forget it. To me, that’s a counterintuitive mindset—follow the ideas and you’ll find a spot for them if they’re good.

Do you view recording and live shows differently?

I believe they’re completely different but equally important. I really enjoy and feel special when I go to a show and see a band that has prepared and practiced their set list the same as when they record an album. It should feel and be apparent to the audience that our show is rehearsed … because it is [laughs].

Every minute on a record and every minute onstage is valuable. If you don’t hook the listener at a show or on an album by the first song, you’re screwed—you have to remember that with track listings and set lists.

Let’s switch topics and talk gear a bit. You used to play a Les Paul with the neck pickup torn out. Was that so you could perform kill-switch-style stops and starts more easily?

I actually ruined the bridge pickup, probably doing something dumb or reckless. I didn’t have any extra money, so I took out the neck pickup and put it in the bridge. I still have that ’69 Les Paul Custom—a Fretless Wonder—and it’s all setup and rebuilt, so I still do play it on recordings all the time.

What other guitars do you use in the studio?

I’ll use anything when I’m recording. Most recently I used a Fender Mustang, a PRS, my Electrical Guitar Company models that are either Plexiglas or aluminum ... whatever is lying around in the studio. There’s no way that anyone can tell which guitar I’m using at whatever point in any song, because one song might have two to five different guitars on it [laughs].

Gear

Guitars

Electrical Guitar Company Custom DC models with Gibson 498T humbuckers

Amps & Cabs

Sunn Beta Lead heads (two)

Carver PM 1.5 Power Amps (two)

Effects

Boss ODB-3 Bass Overdrive

MXR Blue Box Distortion

MXR Dyna Comp

Boss DD-5 Digital Delay

Boss TU-2 Tuner

Strings and Picks

Clayton Acetal Rounded Triangular .63 mm picks

Dunlop Tortex Triangle .60 mm or .73 mm picks

Light Top/Heavy Bottom Strings (various brands) .010–.052

Stylophone

Can you hear the difference?

Vaguely, but I don’t worry about that too much. I’m most concerned with the finished product. Guitars are tools for the artist—that’s it.

I love when people come up to me and say “Your guitar sound was better on Stoner Witch, when you used a Les Paul.” I’m just, like, “What album do you think I only used a Les Paul on? Plus, I used a Fender Mustang reissue on that, dumbass!” [Laughs.]

The band has a dynamic range of sounds and volume levels. How do you manage such big, fast changes in a live environment?

I use my volume controls. I essentially have three volume/distortion levels: Full is with the volume on 10 in the bridge position, middle is with the selector in the middle position and the neck volume rolled off to five, and then the quietest is the neck position with volume at five. I change my tone and volume throughout a set by switching the pickup settings, because almost everything is on, all the time, on full. That’s why I always play a Les Paul-style guitar—or at least one with a similar control setup.

Recently, you’ve been using Electrical Guitar Company Plexiglas and aluminum models a lot live. What do you like about them?

I love the necks, because with it being aluminum, you don’t have to have a tapered neck since it’s so much stronger and stable than wood. It allows me to have a really small neck profile—the thickness is the same at the nut as it is at the neck joint—because I have baby hands [laughs]. I can play faster and more effectively with a thinner aluminum neck than I could ever dream of playing with a wooden neck.

Back to Bass-ics

Melvins' longtime drummer Dale Crover held down the low end on Tres Cabrones, the band's 19th album. Here, he's rumbling with Buzz's Electrical Guitar Company custom V-style bass.

Melvins’ Drummer Dale Crover Picks up the 4-String for Tres Cabrones

What was it like to see someone else play drums in the spot you’ve held for nearly three decades?

Mike is great. It was a joy to relinquish my seat and get him on our 19th record … we made him wait [laughs]. His snare beats in parts of the album were a trip to watch him record—it’ll be fun trying to figure that out for live shows in the future.

You’ve played in Fecal Matter and guitar in Altamont. How was it recording bass instead of drums?

It was easier. When you play bass, there are a lot less things you have to worry about, like miking and noises leaking into mixes. Bass is pretty straightforward, so I felt like I was a part-time employee. I did end up doing some percussion overdubs, but Mike laid out the backbone of all the drum parts on Tres Cabrones. Plus, I always knew if I sucked too bad, I could just punch my way through a track [laughs].

What gear did you use to record your bass parts?

I used a Mosrite Ventures bass for a lot of the parts. [Nirvana’s] Krist Novoselic came down and jammed with us, and he left one of his Gibson Ripper basses so I used that for a couple songs. The Mosrite has more of a midrange tonal frequency where it can sound like a really heavy guitar, but Krist’s Ripper was a beast. That thing brings the low end like you wouldn’t believe.

For amps, I mainly used a Gallien-Krueger 400RB through a single 15", and for an added dimension I ran my basses through Buzz’s setup with the Sunn Beta Lead heads and cabinets that have 12" and 15" speakers in them. That filled out the G-K’s basic tone frequency with some beefiness. Bass and guitar should never really take a long time to get a good sound. If it does, you’re probably doing something wrong or worrying about the wrong thing—if it doesn’t sound good, keep turning it up!

Were there some things you learned about yourself as a bassist or rediscovered during the sessions?

I play guitar quite a bit at home and I play bass, but I got to remember what it feels like to come up with a fresh, usable, complementary bass line or part. It’s a rush or appreciation that only another musician or artist can comprehend. Plus, I enjoy playing bass because there are only four strings, so it’s easier to tune than a guitar and it’s a hell of a lot easier to set up than drums—three of the bass strings are spares anyways [laughs]. Also, it gave me a fresh perspective and understanding for the musical landscape and where bass fits.

We played some faster, punk-rock-style songs to keep things simple and fun for Mike and me—I can show anyone those bass lines because they’re pretty basic. I reconnected with focusing on the rhythm, staying in the pocket, and not messing up. I just tried to come up with bass lines that didn’t sound like Buzz’s parts and to not sound like a drummer was playing bass.

You speak as if you’re a beginner, but the bass lines on “American Cow” are as good as any in the Melvins catalog. They really intertwine nicely with what Buzz is doing on guitar.

I’m proud of that bass line, because it’s different than what Buzz is doing on guitar and it reminds me of the Laughing Hyenas bassist Kevin Strickland, who almost took over as the lead instrument in the band. It’s my best imitation as a bassist … where I don’t sound like a guitarist trying to play bass. But I think my favorite song on Cabrones is “City Dump,” because it’s rocking and the song is still stuck in my head.

What did you use on the album’s heaviest songs—like “Dogs and Cattle Prods” and “Psycho-Delic Haze”—to get the overdriven bass tones?

For any of the super-overdriven stuff, I used Buzz’s Boss ODB-3. That’s what’s nice about playing in a band with a guy with so much crossover gear like Buzz’s rig with the bass distortion pedal, the 15” speakers, and those heavy Sunn heads. All that distortion on those songs helps covers up my sloppiness.

In recent years, you and Buzz have incorporated drummer Coady Willis and bassist Jared Warren of Big Business for live shows. What’s it like playing with two drummers in an already loud band?

It’s bombastic. It’s brutal. It’s fun. We’d had the idea to do that for a long time, since we played in Fantômas/Melvins Big Band and I drummed alongside Dave Lombardo. I don’t think it would work in a quaint jazz quartet, but for our raucous stuff it fits pretty well.

It’s just like two guitarists in a band, right?

Totally. People seem to think it’s hard to do because it’s two guys keeping time and all we’re doing is completely doubling all the parts, but where it gets interesting and the full power is felt is when we’re both doing different beats and fills but still complementing each other and the song. It’s like Thin Lizzy—about 50 percent of the time we’re playing in sync and the rest of the time one of us is following the other or playing our own parts that fit together, depending on what the song calls for.

You’ve recorded almost 20 albums with the Melvins. What were some of the highlights while working on this one?

I think just bringing Mike into the fold—and it being the first time we recorded officially together—was a blast. We always have fun working as a unit, but this time we did some really funny stuff. I had Mike rhythmically make spitting noises in parts of “Tie My Pecker to a Tree”—I filmed it, too—and having him do a Goofy-like laugh in time was hilarious. Those both were my ideas, and I made him do them like a little brother—I was cracking up and he kept messing up his takes [laughs].

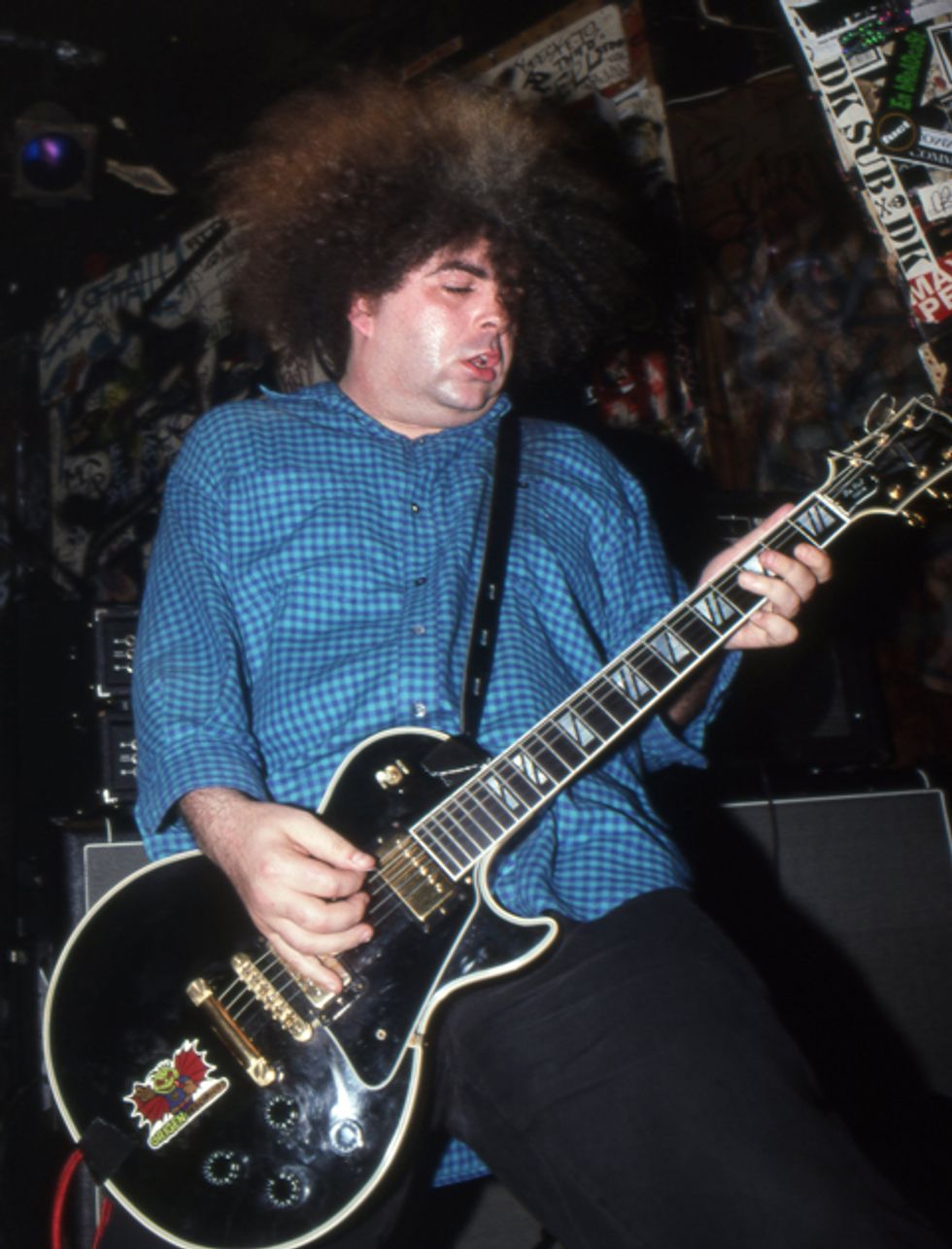

King Buzzo with his trusty black Les Paul Custom at a show in '97 at the infamous club CBGB while supporting the band's 9th album Honky, the band's first after three major releases on Atlantic. Photo by Frank White.

Have you noticed any tonal benefits of that unique construction?

The Plexiglas and aluminum guitars have a more robust low end and a clearer, fuller high range. It blows me away when people tell me that my sound is less impactful and huge onstage. It’s like, “Don’t you think I took the time and resources to A/B my rigs? Geesh!”

There are so many fuzzes on the market these days, some new designs and a lot that try to capture the magic of old, rare pedals. You’re a huge fuzz fan, but you stick with your trusty MXR Blue Box and Boss ODB-3.

I realized a long time ago that gear has to last, especially when you take it on the road. If I’m in Omaha on a Thursday night before a gig and my vintage fuzz box goes to shit, can I go to the Guitar Center and pick up a new rare Big Muff? Probably not. So that’s why I opt for gear that is dependable and obtainable in most markets—and yes, it does have to sound good, too. For live gigs, I’ve gotten used to playing through pedals that you can get anywhere. On top of that, you could have the sweetest boutique rig ever but if you play a shitty club in Albuquerque with bad acoustics and P.A., your platinum rig will sound like dog shit. If my Electrical guitars go to shit, I know I can play a Les Paul and I can get Boss and MXR effects anywhere and still play a superb gig. My philosophy is a poor carpenter blames his tools.

And yet you opt for boutique brands like Electrical Guitar Company and Emperor for guitars and cabinets?

Initially, Kevin [Burkett, Electrical Guitar Company founder] didn’t know who I was—he just knew I was into his guitars and he was happy to make me the exact guitar I wanted. It’s a joy to work with him, and I have a feeling people will look at his work in 30 or 40 years and realize his excellence in the same manner that Travis Bean guitars are revered today.

The Emperor guys helped us out before our Melvins Lite tour because bassist Trevor Dunn plays standup and it was a feedback nightmare. They specifically built us a bass cabinet designed for a standup bassist. And because they’re rad dudes, they built me a matching guitar cabinet—and cases—with a 12" and a 15" speaker. And for my standard Melvins rig, I use an additional Emperor 2x15 cabinet.

“Dogs and Cattle Prods” is like a song trilogy in one jam: The first part is punk, with funky parts that warble with your vocals, the second part is a sludge fest, and the finale is an acoustic voyage. How did that come about?

That’s my favorite song on the record.I realized very quickly that the two first parts went together beautifully, and we planned the whole thing out with that in mind. The last part I wrote later as an extension of the second part.For overdubs I usually just dick around with the guitar, trying various things until I find a part and sound that fits in. Sometimes I get that in a matter of minutes, and others it takes a few hours. You never know, but I like searching—that’s what’s so fun about playing guitar!

How did you get that moaning feedback in the background of “American Cow” and “Dr. Mule”?

What I did for that song—and most songs with that type of a guitar overdub—is, once the hard part and the bulk of the guitar tracks are laid down, I’ll go back, listen, and sit around fiddling with my Sunn Beta Lead solid-state amps and guitar to get the appropriate sound or feedback to musically complement the song.

I used to play through a 4x12 and a 2x15, but the last few records I’ve found that just using the 2x15 for overdubs sounds better. The 15" speakers give it a unique tone within the mix. Obviously, it has more low-end oomph, and to my ears, it got rid of the high-end whistling feedback made by my 4x12 cab. Using just the 2x15 cab live doesn’t give me enough bite, but the 4x12-and-2x15 combination is unbeatable.

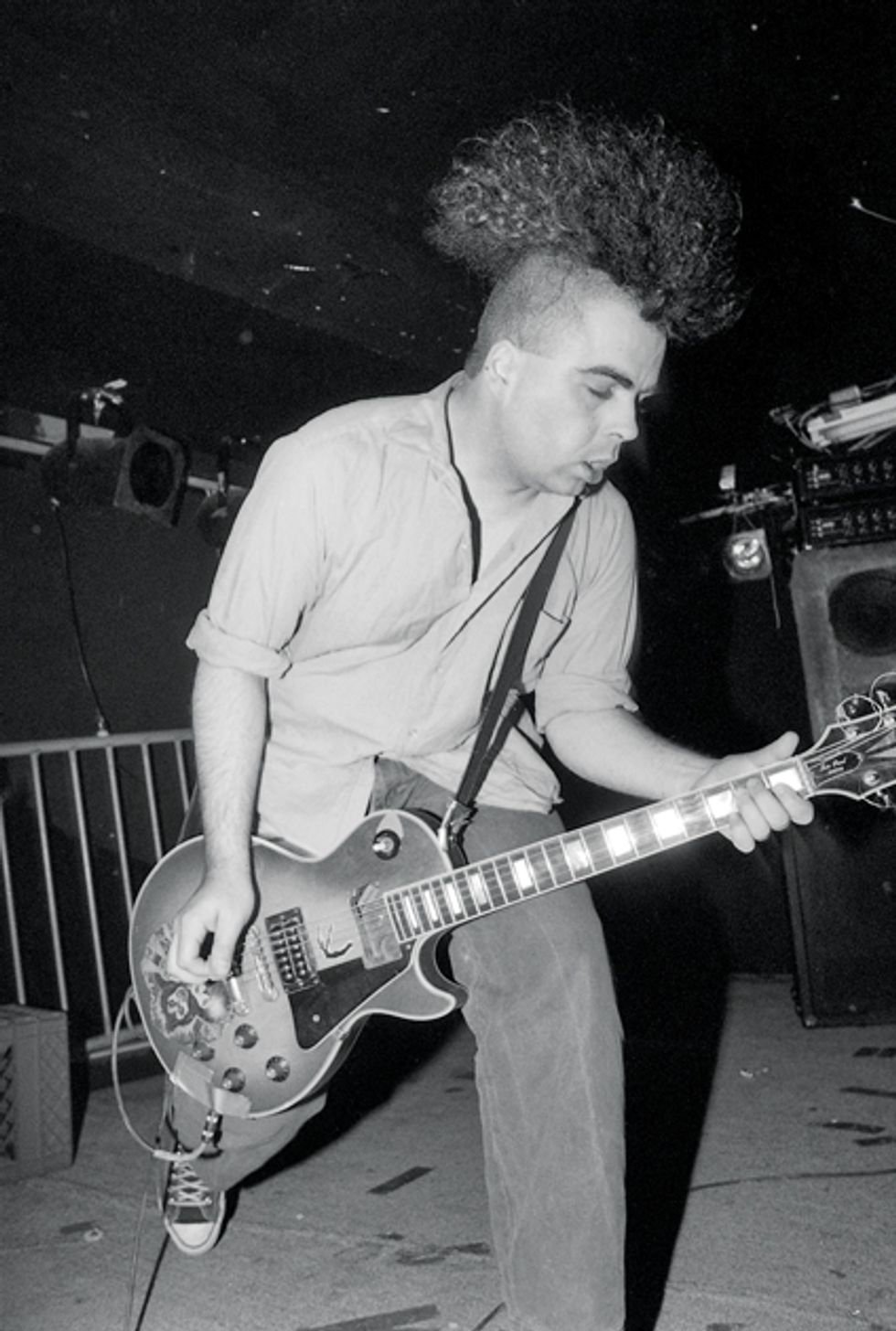

Here Buzz is rocking out during the band's set at the Apocalypse in Toronto, ON, on May 11th, 1990, with his aforementioned '69 Les Paul Fretless Wonder that has its neck pickup in the bridge position because he didn't have money to replace the original bridge pickup. Photo by Derek von Essen.

You’ve been using Sunn Beta Leads for a while. What do you dig about those?

I know everyone prefers tube amps—and I love my Marshall stack and my Mesa/Boogie TriAxis—but for my live tone, I can’t beat those Sunn heads. They’re amazing. They’re dependable. But tonally, when they’re paired with the Carver PM-1.5 power amps, they’re monsters with plenty of gain and a real tight low end that doesn’t cause my speakers to flub out—because those 15" speakers could cause it to lose some definition.

On The Bootlicker, we even recorded guitars direct out of my pedalboard into the mixing board, with no amp modeling or anything. We just messed with the signal afterwards. If you have the patience, you can make it work.

How did you create those carnival-gone-wrong sounds in “Dr. Mule”?

It’s a Stylophone. If people don’t know what that is, look it up. I use them all the time. I’ve made those things sound like giant organs, but I’ve barely even touched a keyboard. It’s a pocket-sized synthesizer that was, like, $30. It gets confused with an octave fuzz or a gnarly keyboard, but it’s just this little device I’ve had for a long time—it’s a great studio tool.

You play deep string bends extremely accurately, and you have a very unique left-hand vibrato technique—as evidenced on the new tracks “Dogs and Cattle Prods” and “Psycho-Delic Haze.” How did you develop those?

I always had a pretty good vibrato for some reason. I’ve had people give me shit about it in the past because they think it sounds generic, but I love it. Lately, I’ve really been into long string bends that sound like I’m using a Whammy pedal—long, unnatural-sounding bends ending with heavy vibrato.

As for how I learned that stuff, you won’t find it in the Roy Clark Deluxe Big Note Guitar book. I don’t read music, and I have no understanding of chords or how or why they work. For me, that knowledge is pointless, and after playing guitar for about 33 years I see no reason to seek that out now. In my opinion, technical ability and a broad understanding of musical notes written on paper has very little to do with making music. I love writing, recording, and performing songs. I spend about 70 percent of my waking hours doing just that. If you discount all of the hard work I do in this regard, then it’s all down to luck. There’s an old saying in golf that says the more I practice the luckier I get [laughs].

How exactly do you play those deep, Whammy-like bends?

I just used my fingers and played two different takes, and then combined them for the recorded solo. I’ve always been practicing and trying to improve my left-hand vibrato technique, because those are my favorite types of solos—the ones that sound like a pitch-shifting pedal or a guitar’s whammy bar. It sounds so expressive. To me, using pedals for those effects sounds sterile and rigid. I prefer the loose, fluid feel you can get with using your fingers. I think it also helps that I use custom-gauge strings with heavy bottoms and light tops.

Why do you prefer larger, triangular picks?

Because it’s three picks in one. I keep rotating it all night when I’m playing a show, trying to get the sharpest, pointiest edge. Because of my ham-fisted strumming, I am constantly wearing out the picks. After each show I’ll take the corners of the picks and rub them on the carpet, and that burns the burs off them and they’re good as new. I also like having the give of the thinner pick, because it gives a little thaw and snap to my tone since I attack so hard. If I used a thicker pick, I’d snap it.

What’s just as unique about your style is that many of your songs have odd time signatures and don’t follow conventional rock-song structures.

Someone like Captain Beefheart was never worried about song structure or standards, so why should we? We just write and construct what we’d like to hear. We’re not perverse or trying to do something different to be oddballs. People should expect the Melvins not to do those things. The Beatles are an overall easily accessible band loved by millions, but their songs “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey” or “Helter Skelter” are completely unconventional songs not of the pop formula, but are absolutely beautiful. A good song is a good song no matter its meter or how many times the chorus appears.

YouTube It

Thanks to the internet, we're blessed with a plethora of Melvins live clips, so here are three to wet your appetite.

Feel the raw hours of power that ensues when the Melvins’ Buzz Osbourne and Dale Crover mash up with Big Business’ Coady Willis and Jared Warren.

This clips proves that standup bass has a spot in sludge rock as Trevor Dunn (Fanotomas and Tomahawk) join Buzz and Dale for a raucous set as Melvins Lite.

Enjoy the Melvin’s Houdini—their ’93 tour de force—from front to back in this 2005 show.