Although these days Neko Case is well known as an indie-minded chanteuse, those who trace her career back to its mid-'90s roots may find a few surprises. For instance, during her time in the Pacific Northwest she was a member of various punk bands, but then her 1997 solo debut, Virginian, ended up knee-deep in conventional country and western trappings (there's even a tune called “Honky Tonk Hiccups").

Today, Case has found something of an adopted home in the alt-country scene, yet she continues to defy the industry's affinity for lazy labeling. While it's been five years since her last solo statement (2013's The Worse Things Get, the Harder I Fight, the Harder I Fight, the More I Love You), Case—who also fronts Canadian indie-rock outfit the New Pornographers—has actually been on a rather monastically dedicated bent as a musician.

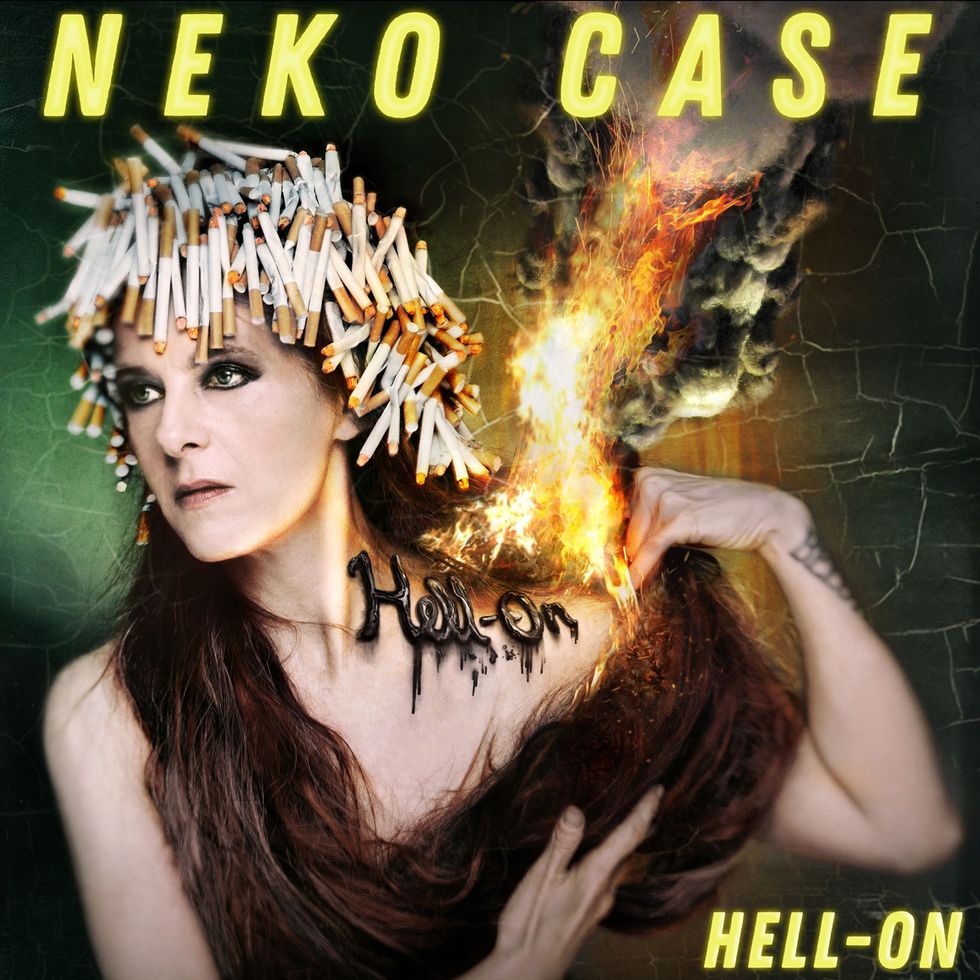

True to form, the tenor-guitar-loving singer-songwriter's latest solo outing (and seventh overall), Hell-On, showcases an artist at the pinnacle of her craft collaborating with a rotating cast of similarly independent-minded artists, including Lang, Veirs, Mark Lanegan (Screaming Trees), Doug Gillard (Guided by Voices, Nada Surf), Steve Berlin (Los Lobos), and Eric Bachmann (Crooked Fingers, Archers of Loaf). Case's music has long been a complex stew of disparate influences simmered into something uniquely her own—an ideal vehicle for her charming lilt and storytelling prowess—and Hell-On puts those gifts on full display. Dressed up with plenty of '60s girl-group vocal harmonies, clever guitar work that's both atmospheric and unexpected, and prog-informed song structures, Hell-On's songs constitute a concentrated, disarming dose of her best attributes.

As a guitarist, Case came to the instrument somewhat late in life, and she soon discovered that the 4-string tenor suited her best—so much so that she developed her signature percussive playing technique around it. (She's also amassed quite a collection, including an incredibly rare '50s Gretsch Duo Jet tenor formerly owned by Ry Cooder.) In addition, like most other revered songwriters, Case has surrounded herself with musicians equal to the task. She and her longtime tandem of stringed swingmen, Paul Rigby (lead guitar) and Jon Rauhouse (pedal steel/rhythm guitar/banjo), artfully walk the line between nuanced supporting roles, athletic intrigue, and weaving parts together as one. The guitar work on Hell-Onis admittedly biased towards the former, but stands tall as a masterful display of layered atmospherics.

Premier Guitarrecently spoke with Case, as well as trusted multitasker Rauhouse (see sidebar “Jon Rauhouse: On the Road with Neko"), about making the new record, performing it live, and the respective delights and challenges of tenor and pedal-steel guitars.

You came to guitar after years of success and experience as a singer. Can you tell us a little about that journey?

I didn't get started playing properly until I was, like, 30, and if it weren't for the tenor guitar, I don't know that I would've gotten started at all. I didn't really start successfully playing guitar until I got a tenor, because I've got really tiny hands. I play 6- and 7-string, too—I'm open to anything. That's one of the great things about learning an instrument a bit later in life. If you teach yourself to play something and you're not a kid, you're really not worried about learning scales or doing things “correctly," so it's a bit of a free-for-all. I find that to be much more creative. Granted, I can't just show up at a jam and play, but I'm not interested in that kind of thing anyway. I don't play the guitar like most people do—I'm kind of like a percussionist more than a traditional guitar player.

What can you tell us about the 7-string—and did it make any major appearances onHell-On?

Yeah, it makes a lot of appearances. It's a Roger McGuinn signature model Martin [HD-7], and it's been the greatest thing in my life for quite a while. It serves an important purpose because I play the guitar so percussively and I want it to jangle and have a more dulcimer-like resonance, but playing a 12-string is really out of the question because I have a reallyhard time making chords on a 12-string.

TIDBIT: Neko Case was finishing Hell-Onin Stockholm, Sweden, when she learned that her Vermont home had burnt to the ground. Rather appropriately, the next day she tracked the first single, “Bad Luck."

With the Martin, the 7th string doubles the G string, which gives you a lot of the resonance and jangle of a 12-string without having to tune it all the time—it stays in tune remarkably well. It gives me the sound I'm looking for in a 12-string without any of the problems. It totally makes sense that Roger McGuinn came up with that concept, considering the amount of time he's probably spent tuning 12-string guitars over the course of his career. I hope Martin makes them again, because they're such a great idea.

With the tiny-hands thing, I just needed something that sounded like music pretty much immediately to feel like I was making any progress. When I was trying to learn to play a 6-string in my 20s, I had a really cheap guitar with a really wide neck, which didn't help me. I never felt like I was making any progress and it just didn't sound musical to me. With the tenor, it sounded musical right away and I was able to start writing songs with it quickly, which was how I gauged whether or not I was making any progress. Guitar wasn't fun for me when I wasn't able to make music with it. That said, playing the tenor for so long has stretched my hands out and helped me build up the muscle to play regular 6- and 7-string guitars without a problem—in fact, I actually didn't play any tenor guitar on the record this time! I can't make really complicated chords with big fret stretches or anything, but I'm not really worried about it. One of my favorite guitarists was Pops Staples, and he would just use the sound of the instrument to do his thing. Pops left huge spaces between the notes and let the electronics and sound of his Jazzmaster ring out and carry things, and that sound and idea is sobeautiful to me!

Though she says she's not currently looking to add to her extensive collection of tenors, Case says she'd make an exception for an instrument similar to this weathered vintage Martin 5-17T. Photo by Tim Bugbee

Does the songwriting process typically start on guitar for you?

Probably 30 percent of the time it does, but usually I have lyrics first and thenI'll play guitar and find things that work. I'm at a point where my regular 6-string guitar work relies on different tunings to find new ideas. I can't recall what it is off the top of my head, because it's one that Laura Veirs made up that we call the “supermoon" tuning after a track from the Case/Lang/Veirs album. It makes a gorgeous sound that makes really pretty voicings of things easily, and I used it on a track on this record called “Oracle of the Maritimes."

How did songwriting collaboration impact this record, particularly cowriting with your New Pornographers bandmate Carl Newman for the first time, and bringing Björn Yttling [Peter Björn and John] into the mix?

Björn coproducing six songs on the record was so awesome and liberating. It felt so good to give someone you admire as I do Björn some stem tracks and ask, “What sound do you think is the next step on this?" It was so exciting and liberating to not make those decisions. I wanted to break myself out of my habits and learn new things, and especially after collaborating with k.d. [lang] and Laura. I've always collaborated with people, but that particular project was different in that we were three singer-songwriters who are completelyin charge of our careers and make our own decisions typically, and we came together to write a record from the ground up, democratically, with a third of a vote each in what happens. That was a very scary thing to do, coming from a place where I've always had veto power. There were moments that were uncomfortable, but when we looked back after the record was made, we were all so happy about how it turned out. I learned how to relax and let go, and I found it often served the song better. When you're loose and do some free-falling, rather than pushing in the direction you already know, it can often give a track the change it needs.

Trusting others is something I've always done with the New Pornographers, because I don't write songs in that band—I just show up and do what they want me to do. I might make up my own harmony parts, but for the most part, Carl and Dan [Bejar] are the songwriters. The Case/Lang/Veirs thing was the first time I really let go on songs I helped write. It really reminded me that collaboration often involves relinquishing your total say, but it was really a great learning experience and it applied well to the solo record. I just didn't want to make the same thing again, and at a certain point it's good to go, “I need to learn a little bit here." A really important thing about that trust and the free fall is that you do that after you've done a lot of research. It's not something I did capriciously or without having done a lot of exploration. There's a point where you go, “I'm working with people who know what they're doing … I'm working with people responsible for music I love." It makes it a lot easier to let go when you stay aware of that.

You've amassed a pretty incredible collection of tenor guitars, including an extremely rare '50s Gibson Les Paul Special tenor, and the '59 Gretsch Duo Jet tenor that once belonged to Ry Cooder. Are you still hunting for new ones?

I basically have a moratorium on buying any more tenor guitars. If I find a good backup for one of my tiny Martins, I might, but I don't needany more. I haven't stretched out into anything new in the guitar world, but I have brought in different amps and more effects than I usually use. There's another role as a guitarist that I've started really loving, which is making a soundscape—operating as a noisemaker and adding textures. It's almost like playing the guitar like it's a synthesizer. Not necessarily making a drone, but adding a standing wave of sound that goes through a song. There are a lot of songs on the record that have stuff like that, and I've been really enjoying the Cramps-inspired Human Fly fuzz made by Tym [Guitars] in Australia.

Guitars

Martin Roger McGuinn Signature HD-7

1959 Gretsch Duo Jet Tenor

1950s Gibson Les Paul Special Tenor

1967 Gibson SG Special Tenor

Amps

1970s Garnet Revolution II

Carr Rambler

Effects

Strymon Flint

Tym Guitars Human Fly

Crowther Audio Hot Cake

Strings and Picks

Various D'Addario custom string sets

Dunlop Tortex .73 mm picks

I use that in conjunction with the Crowther Hot Cake, which I think is funny because one's from Australia and one's from New Zealand, so I call it my ANZAC set up [after the acronym referring to soldiers who served together in the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps]. I've also got a really great reverb now by Strymon called the Flint, which is the first digital reverb I've ever preferred to an amplifier. I've been lovingthat thing, and I've never ever liked a reverb pedal in my life. I also use the onboard reverb on my Carr amp.

You're also a big fan of vintage Garnet amps, which seems fitting, as you're recognized as an honorary Canadian. How did you get into those?

Reid Diamond from [Canadian instrumental outfit] Shadowy Men on a Shadowy Planet played Garnets, and [Toronto-based country band] the Sadies were also really into those amps. When Reid passed, I bought a couple of his amps. I gave one to a good friend and I kept one of them. I actually got to meet Gar Gillies [founder of Garnet Amplifier Company] before he passed away. I went to his shop and said hello and he was so sweet—he gave me a speaker! He had this awesome little shop in Winnipeg. He used to make pedals and amps for Randy Bachman of BTO [Bachman-Turner Overdrive], and he was still making the pedals and fixing guitars and amps for Winnipeg locals when we met. He had this really great old hospital gurney that he would roll the sick amps around on. He was such a sweetheart, I'm so glad I got to meet him before he passed away.

Which model do you have, and what do you like about it?

I have a Revolution II. They sound completely different from other amps, but it's hard to explain what it is. I don't tour with mine, because I don't want to screw it up—it's a studio-only amp. I tour with the Carr because it's a lot more hearty.

What is it about Jon Rauhouse's playing that's made him the right guy for you for so long?

He's just so great and excited and ready all the time. “What do you wanna play, babe?!" That's the first thing he says to me every time we get onstage. Jon really is a greatplayer, and there aren't that many pedal-steel guitarists out there—and even fewer that are still trying to learn new things about the instrument. For the most part, they're a dying breed, which is a horrible thing to say. But it's great to work with someone carrying the torch for that instrument. Jon is someone who still does research and seeks out pedal-steel music that he hasn't heard. Rauhouse really lives for it.

There are some very cool, prog-rock kind of structures on Hell-On, like “Curse of the I-5 Corridor" and that closing scene switch-up on “Pitch or Honey." Is that a world you consciously pull from?

I love prog—I've always loved prog! If you're a storyteller and you want to be more linear, prog is your friend. Mathematically, I know nothing about prog, and I'm not as disciplined as most prog musicians. But I'm a huge fan of it. I love King Crimson, absolutely love them!

Based on your sound, some people might be surprised by that admission.

There's this weird idea that country music can't evolve or change, and people get very touchy about progression in country or bluegrass—they don't welcome new things. Country music is a truly great art form and its umbrella covers a lot of other things. It's not onething, so I don't know why people try to force it to be one thing. It can still grow—it's not like there isn't room for that! There's this “the song goes with my outfit" nostalgia thing that doesn't work out, and I'm not interested in that.

Armed with a vintage Gibson tenor guitar, Neko Case performs one of her classic tracks, “Deep Red Bells," live onAustin City Limitsas Jon Rauhouse provides a stunning pedal-steel countermelody to her lead vocal.

Jon Rauhouse: On the Road with Neko

Multi-instrumentalist Jon Rauhouse has been playing alongside Neko Case for two decades, whether it be sliding on the pedal steel, twanging a banjo, or providing a backdrop with his 12-string electric. Here he shares his philosophy on contributing to the complex orchestration on Hell-On, and then translating it to a live setting.What are the challenges of bringing a record with big arrangements like those on Hell-Onto life on the road?

You have to pick an instrument and find a part that works in the spirit of what's going on in any given song, which can be tough because there's almost 50 musicians on the record and tons of parts. You can't play exactly the part you played or exactly the part someone else played, so you have to make up an amalgam of what's going on to make the songs really work live. Everyone in the band has to do that. Some of these songs double up drummers—there's a lot of random percussion—but we're touring with one drummer, and he has to find a part that works in a way that's recognizable as that song live. It's the same thing for me: I have to find a hook or something that's more recognizable than a strict part. I'm playing a lot of electric guitar and 12-string stuff on the new songs live.

Your electric 12-string playing is very effective as an atmospheric device.

It is, but I think almost everythinganyone does in Neko's music is atmospheric in a way, because it's really all about her singing, you know? I've been with Neko almost 20 years now and it's always been more of a task to get out of the way of her voice than anything. Even when I listen to her records, I don't want to hear people wanking—I want to hear her singing. So it's all about atmosphere. The 12-string is really good for that, especially simple, first-position fingerpicking things. That lush underlayer tends to work really well with her thing, and the same goes for the steel guitar.I use a delay or an Echoplex, and I like to use a Leslie speaker a lot with the steel. I try to keep it sparse and not get in the way, because there's always big vocal harmonies, and Neko's own lead harmony, and my goal is to create a bed to keep things floating on.

Which steel guitar do prefer when you play with Neko?

My touring steel, and what I use in general, is a mid-'70s MSA single-neck 10-string Pro model with three pedals and four knee levers, in E9 tuning. I love that era of MSA because the pickups sound really great. They break up just a little bit, so I don't need an overdrive pedal unless I want a full-on fuzz tone. I can just turn the amp up a bit and get a really cool overdrive out of those old pickups.

What do you think it is about you and Paul Rigby that works so well together?

I'm always saying if we're going to do something, let's do something together! We always work as a team. A lot of that comes into reallythinking about what your part is as it applies to their part, and then coming together during rehearsal and trying to layer things with one another. That comes from having respect for whoever you're playing with. I'm always really clear about the part I'm going to be playing. Like, I have a banjo solo on the song “Maybe Sparrow" [off Case's 2006 album, Fox Confessor Brings the Flood], and I'm always asking Paul to play it with me. I know it doesn't sound the same, but I'm a big fan of Thin Lizzy and the Allman Brothers and that type of stuff, and I think that if you can find someone to play a cool part withyou, it's way more satisfying. Paul really helps with that. And it's more fun!

Your career as a sideman is rather illustrious, with Neko and otherwise. Do you have any advice for players interested in playing that role or becoming a more universally useful player?

The first bit of advice I give everybody is to play as much as you can, with as many people as you can. Even if you sit down with somebody that technically isn't as good a player as you, or possibly not as strong a songwriter as someone else, you will always learn something from them. I do, at least. If I sit in with someone, they're almost always doing things different from someone else, and you can pick great things up that way. Also, don't play for free—because, for fuck's sake, that's killing us all! But I say play as many gigs and as much as you possibly can.

The other thing is to really try to be as versatile as you can. Pick up different styles, pick up different instruments. I guarantee one of the reasons I've done a lot that I've done is because I can play so many different instruments. If you look at my Instagram page, my station with Case sometimes has a pedal steel, a banjo, an archtop guitar, a resonator, a 12-string, and a trombone. I know a lot of people want to travel lighter and mimic some of that stuff with pedals, but to my ears nothing can replace a real instrument. And be willing to do weird stuff! One thing I did with Neko early on was put a banjo through a [Fender] Vibrolux, with a really big delay on it. It sounded so odd, but so cool. You have to be willing to try things that aren't expected. You have to be versatile andwilling to try a lot of things.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)