What does it mean to have curiosity as an artist? For some, it can mean becoming transfixed with learning the work of a creative idol, or possessing an innate drive to absorb all there is to know about a niche (or all) of music history. Yet, when musically polyglottal nylon-string guitarist and composer Ralph Towner hears “curiosity,” it reminds him not of the pursuit of knowledge, but rather that of writing great music.

Fat Foot

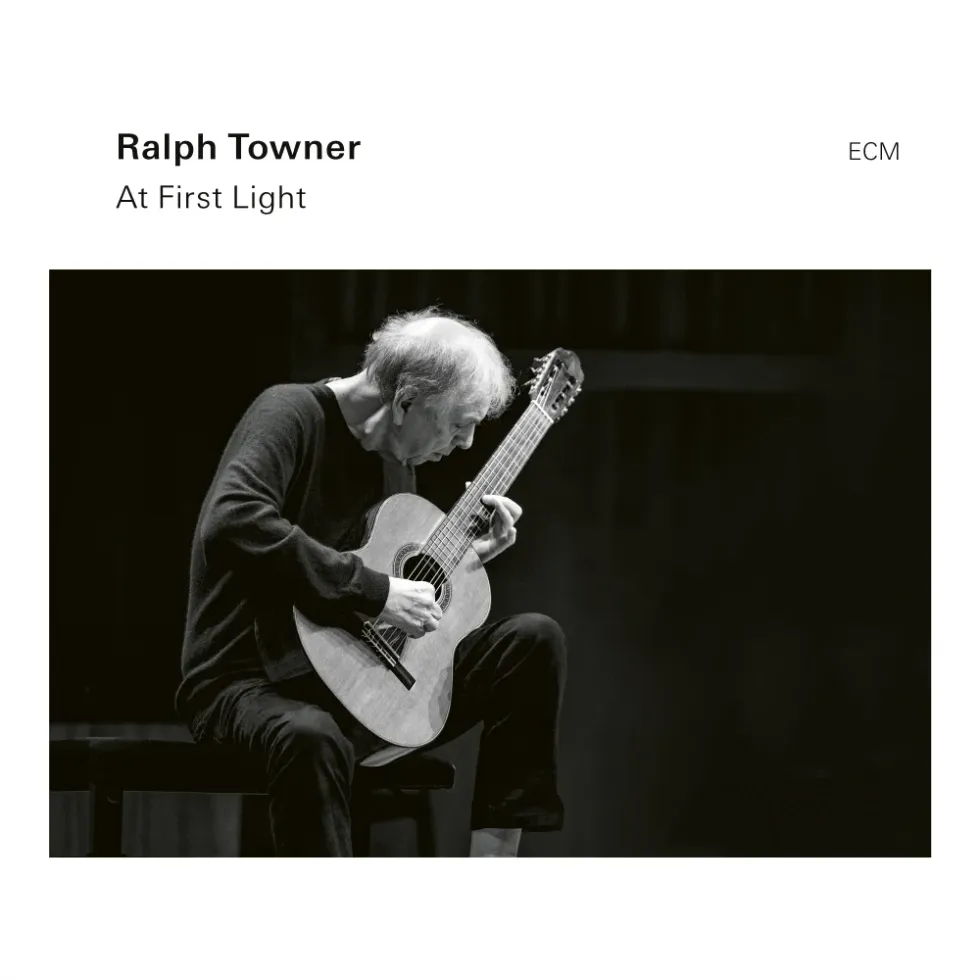

A selection from Towner’s new album, At First Light.

“I’m definitely curious, but less and less so, the older I get,” he comments. “But I’m still involved in this process of writing, and finding that one little germ that makes the start of a composition.

“I’ve been more obsessive than I’ve been curious,” he continues. “That obsession with wondering, ‘Where does this piece of music go next?’ It’s like writing a story. But I wouldn’t define that as curiosity. Because you’re being curious about something that doesn’t exist.”

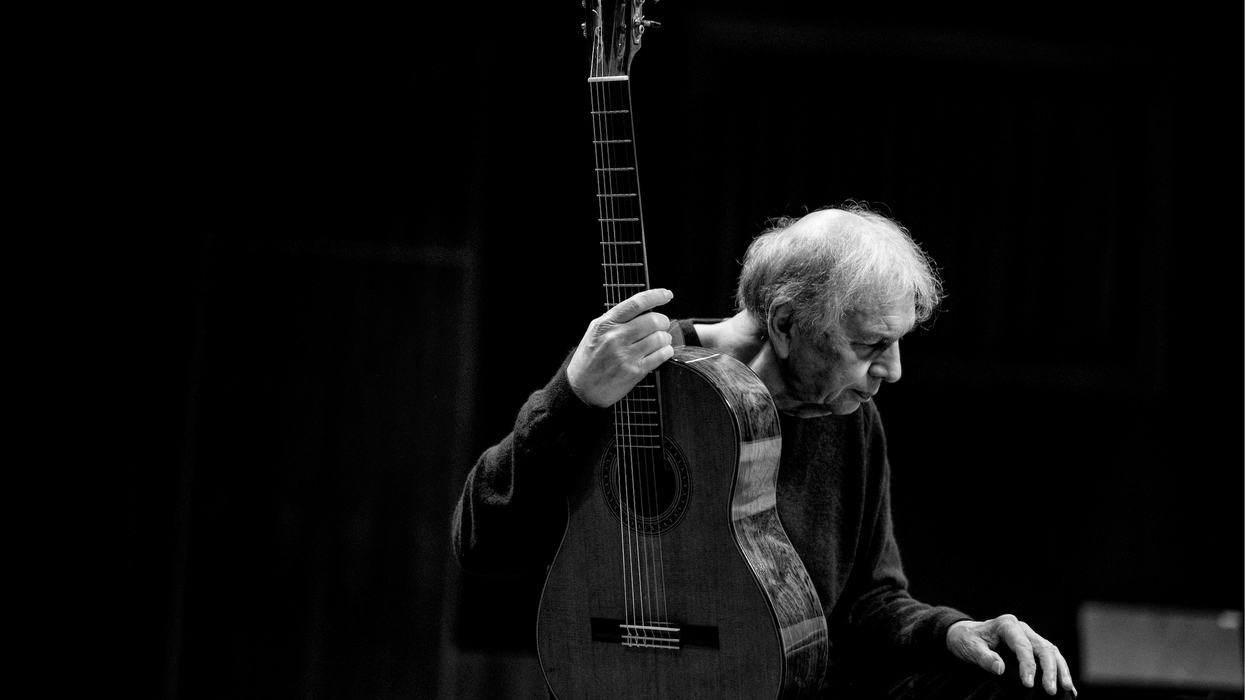

It’s no surprise that Towner—who’s amassed a staggering discography since his earliest days with the Paul Winter Consort, and his 1970 co-founding of the still-active jazz-and-world-music group Oregon, and through a busy, parallel career as a solo artist—has cultivated a strong personal understanding of the composing process. And his new release, At First Light, is the latest product of what the now 83-year-old has been honing on the guitar for just over 60 years. Of the album, he says, “I really felt like I could make another statement as a soloist, so there’s just one classical guitar on it.”

“I wouldn’t define that as curiosity. Because you’re being curious about something that doesn’t exist.”

If you’ve played enough classical or jazz fingerstyle guitar, something about listening to solo pieces of that nature—at least, when performed at Towner’s level—can provoke more carefully realized mental images of the craft itself. When listening to At First Light, I could almost picture the acrobatic formation of various chord and interval shapes by Towner’s weathered-yet-steady hands.

With over 100 album credits to his name as either a bandleader, sideman, or solo artist, Ralph Towner felt inspired to make another statement as a solo guitarist on At First Light.

The album opens with an original, “Flow,” which begins with a spacious, impressionistic passage that soon transforms into a more fiendish motif which reveals itself just twice throughout the piece. Towner’s arrangements of the 1960 standard, Jule Styne’s “Make Someone Happy,” the Irish traditional “Danny Boy,” and Hoagy Carmichael’s “Little Old Lady”—which, as he comments, was famously covered by comedian and musician Jimmy Durante—mostly wink at their inspirations, intermittently sneaking their respective themes into explorative, pleasantly wandering harmonies. Meanwhile, Towner’s original voice persists on “Ubi Sunt,” which unravels with a seemingly cautious sense of searching; “Fat Foot,” which speaks with the assertive cadence of a downtown urbanite; and the aptly named closing track, “Empty Stage,” which conveys a somehow friendly, harmless angst.

At First Light was recorded in a large, empty auditorium in Lugano, Switzerland, and produced by Manfred Eicher, who Towner’s been working with since the early ’70s. Towner, who currently plays an Australia-made Jim Redgate classical guitar with a cedar top, dislikes pickups in acoustic guitars, eschewing them for external microphones. “Microphones more accurately reproduce the actual sustain of the strings, and pickups, though greatly improved with better technology, tend to make an artificial increase in volume and sustain that make up the very refined nuances that are controlled on the nylon-string classical guitar,” he shares. The songs were recorded with Schoeps microphones, and their sequence on the track list is that in which Towner performed them. “I can hear my hands getting warmer, and my tone getting stronger as the recording goes on. Maybe only I would know this,” Towner reflects.

But long before At First Light, and before he accumulated the over-100 other recording credits he has to his name today, Towner grew up in “semi-poverty”—as he puts it—in Chehalis, Washington, with two older brothers who served in World War II and a mother who taught piano. “I would hear these influent piano lessons from the back room from the time I was very young,” he shares. She taught him piano before he later began learning trumpet around the age of 6, and the two would play duets together—with her on the former instrument and him on the latter.

“On the trumpet, you learn about how to control your breath and what breath is,” Towner elaborates. “The thing that really is important on the more machine-like guitar or piano is to develop and connect it with breath and delivery. Yet, you have to honor what each instrument does, or what it’s capable of doing. To make a piano sing requires a different kind of thing.”

Ralph Towner's Gear

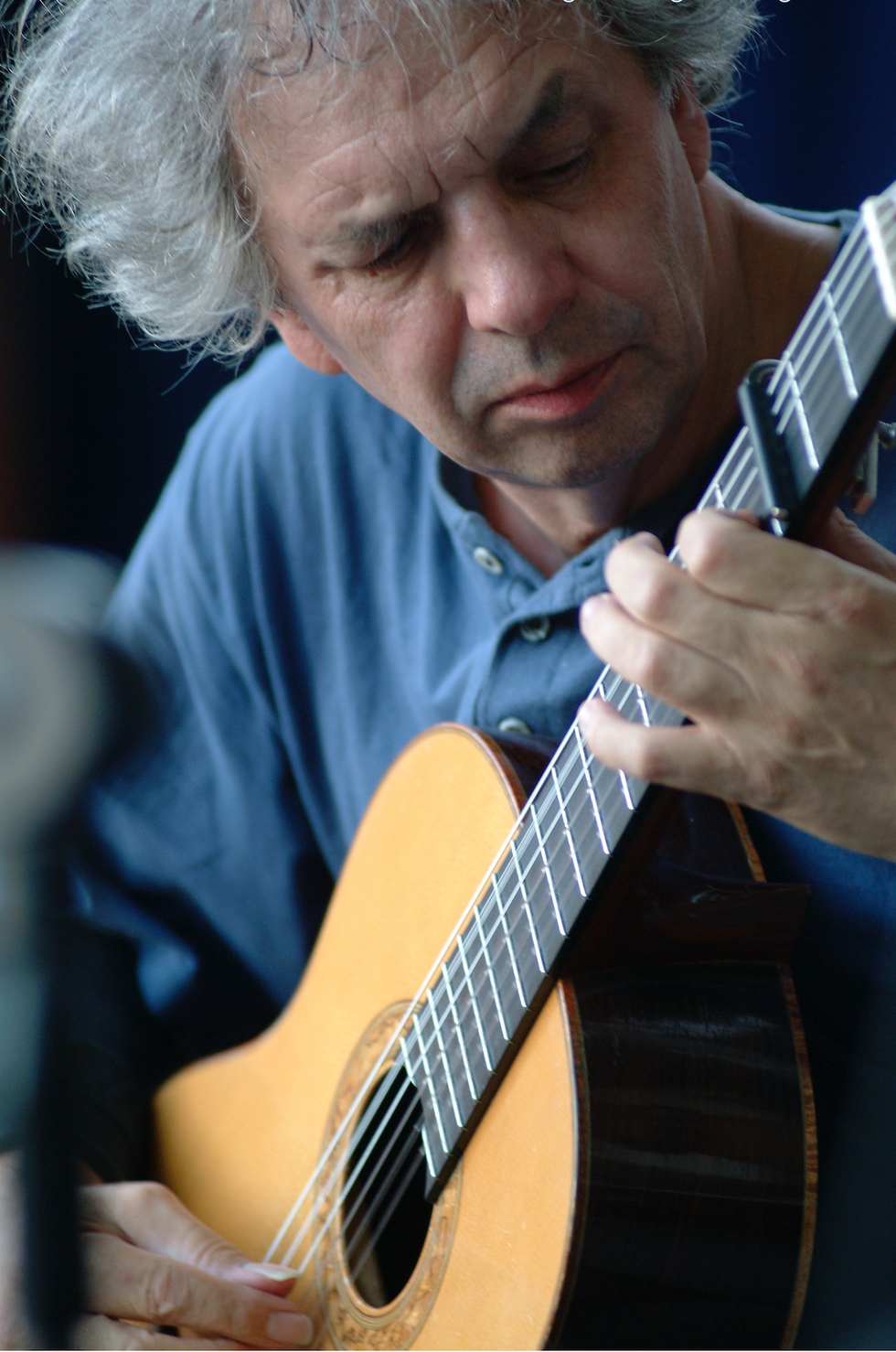

Although his focus has been guitar for the past several decades, Towner is also a trained pianist, and learned how to play the trumpet as a child.

Photo by Paolo Soriani

Guitars

- Jeffrey Elliot spruce-top classical guitars

- Cyndy Burton spruce-top classical guitars

- Jim Redgate cedar-top classical guitar

- Two 1974 12-string custom Guilds

Strings

- D’Addario EJ45 Pro-Arte Normal Tension

He went on to study piano at the University of Oregon, where he says he could barely make ends meet, and worked in a beet-and-bean cannery during the summer. Then, at 22, he heard the classical guitar for the first time when he saw a student performing Bach on the instrument. That’s when he dropped everything and moved to Vienna to study at the city’s Academy of Music, where he devotedly shifted his musical education to the nylon-string, and focused on learning Renaissance, Elizabethan, and lute music.

“Being able to play bebop was almost like … a badge that would get you in the door.”

When Towner moved to New York City after his graduation in the late ’60s, it was on the piano that he first made a living, and he found that the way for him to do that at that time was by playing jazz. But, “We didn’t have jazz schools back then,” he shares. “It helped to have a friend who was a bass player; that really made a big difference in how I learned and worked on the piano, enough to actually play gigs on it.

“One thing that was important when I moved to New York was to be able to play a passable version of bebop,” Towner continues. “Being able to play bebop was almost like … a badge that would get you in the door.” As one of the world’s biggest “small” towns, the city was fertile in the sense of how quickly that entry led to important connections. “I remember going over to Wayne Shorter’s apartment and we played each other’s music on cassettes or on his piano,” he shares, “and I spent a whole afternoon with him. This was about two years before Weather Report.”

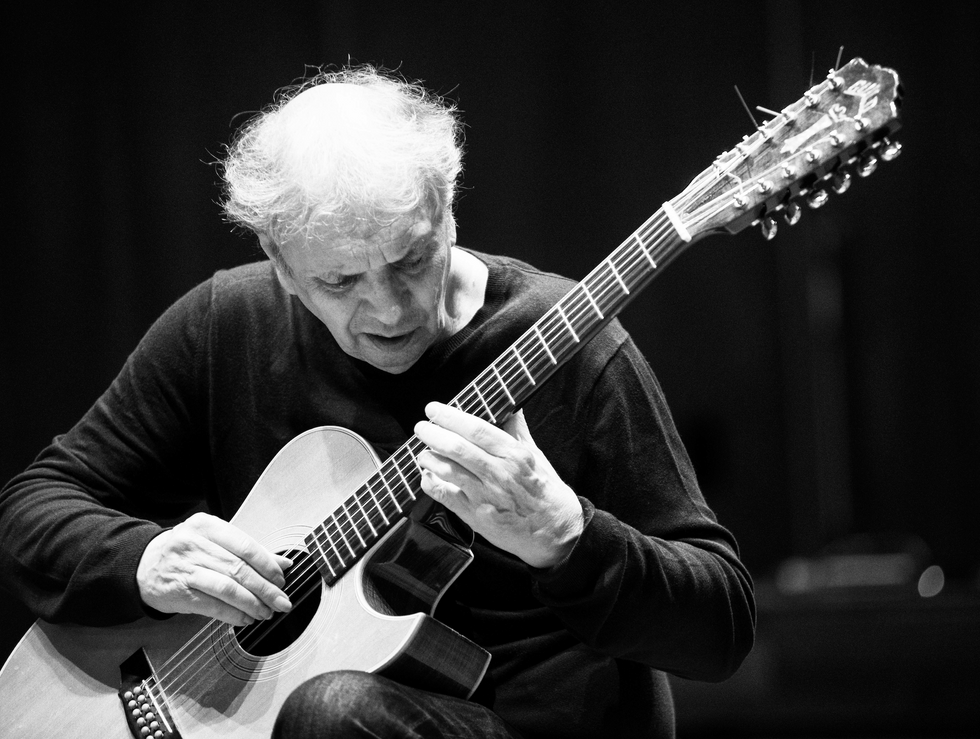

When he lived in New York City following his graduation from the Vienna Academy of Music, Towner found that knowing how to play bebop was what gave him entry into successful musical circles.

Photo by Caterina di Perri

The guitarist’s first big break came when he joined the Paul Winter Consort not long after his New York move. (Only a handful of years later, during their 1971 mission, the Apollo 15 crew named two lunar craters after two of Towner’s early compositions for the group, “Icarus” and “Ghost Bead.”) Shortly after joining the Consort, he was featured on Weather Report’s I Sing the Body Electric, recording the intro to “The Moors” on a 12-string guitar; released a debut album with Oregon, Music of Another Present Era; and a year later, debuted as a solo artist with Trios / Solos (beginning a now 50-year relationship with the ECM label). In the five decades since, Towner has collaborated with artists such as Gary Peacock, Vince Mendoza, Jack DeJohnette, and Bill Bruford, and also distinguished himself with his penchant for playing improvised music on the 12-string guitar, while growing his stature as a nylon-string guitarist.

Today, as a composer, Towner remains fascinated by the creative process. “When you find what’s really an idea that seems to speak, it’s a logic of music,” he shares. “You sort of telescope this first event, and everything that follows is related to the initial idea. It unravels like a story, because you sense when something’s right for where you’re going with it as you go. You wouldn’t write a lyric that would change midstream. So, it’s got a big relation to the spoken word and literary content. There’s a logic to the music that’s also kind of an emotional logic too.”

“That’s an invitation to have a musical accident…. Nothing gets hurt, but maybe your ego.”

In comparing musical compositions to literary content, Towner draws a bit of a contrast to what one might rightfully expect of his influences, given his extensive catalog of instrumental music. He elaborates, “I didn’t even bother to listen to the Beatles at first, for about two, three, four years … and then was really stunned with this kind of doggerel,” he says, continuing, “I used to be very critical of Bob Dylan, always making fun of the way he sang. But then I wised up and started reading the lyrics. I started hearing his delivery when he sang … which is only his, truly his, but was very musical.

Getting back into performing live after the pandemic was challenging for Towner, who said that during his first few return performances, he would get easily distracted.

“Then I discovered pretty recently, maybe 10 years ago,” he shares, “[My wife and I,] we’re in the car and she said ‘Oh, listen to this.’ And she’s quite a fan of English rock, art rock. And I finally heard…. Oh, god, help,” he says, struggling to place the name. “Uh, Led Zeppelin.”

Something else new to Towner is the concept of “imposter syndrome”—a type of self-doubt even Eric Johnson has alluded to experiencing—and he has trouble finding honest examples of when or if he’s ever identified with it. His confidence was indeed shaken, however, by the pandemic, at least in terms of giving live performances. “The first concerts I did [when the world returned to performing] were like, my god, I don’t even know how or where to put my mind, or what I’m playing. I’m thinking like, ‘Gee, did I leave the gas on at home?’ That’s an invitation to have a musical accident. Like a car accident, except it’s music. Nothing gets hurt, but maybe your ego.

Ralph Towner - If(Live in Korea) Pro Shot

Ralph Towner illustrates his impressive dexterity and singular touch on the classical guitar in a live performance of his song “If.”

“I still haven’t had that many concerts, but I think in the last couple, I’ve found out how to begin in that space where you’re kind of hovering above, hearing the music that’s actually coming out of your instrument, but you’re also able to hear it in a distant way, almost as if you’re part of the audience. There’s a little place you suspend yourself in when you’re a performer.”

And while it’s not the first time an artist has described inducing that pseudo-out-of-body experience in order to better express themselves in their music, Towner’s sage perspective proves its worth in the inimitable quality of his playing, whether it’s live or recorded. Looking back on what most would describe as an overwhelmingly full career, he says, “It was like a piece of music in its way, whether it was good or bad. So, when I’m fiddling around wondering what I would have done, I didn’t do anything that I regret at this point.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)