The term “busking” first popped up in the English language in Great Britain around the middle of the 19th century. It derives from the Spanish buscar, meaning “to seek,” and refers to outdoor performers playing for tips from passersby. In America, we call them street musicians.

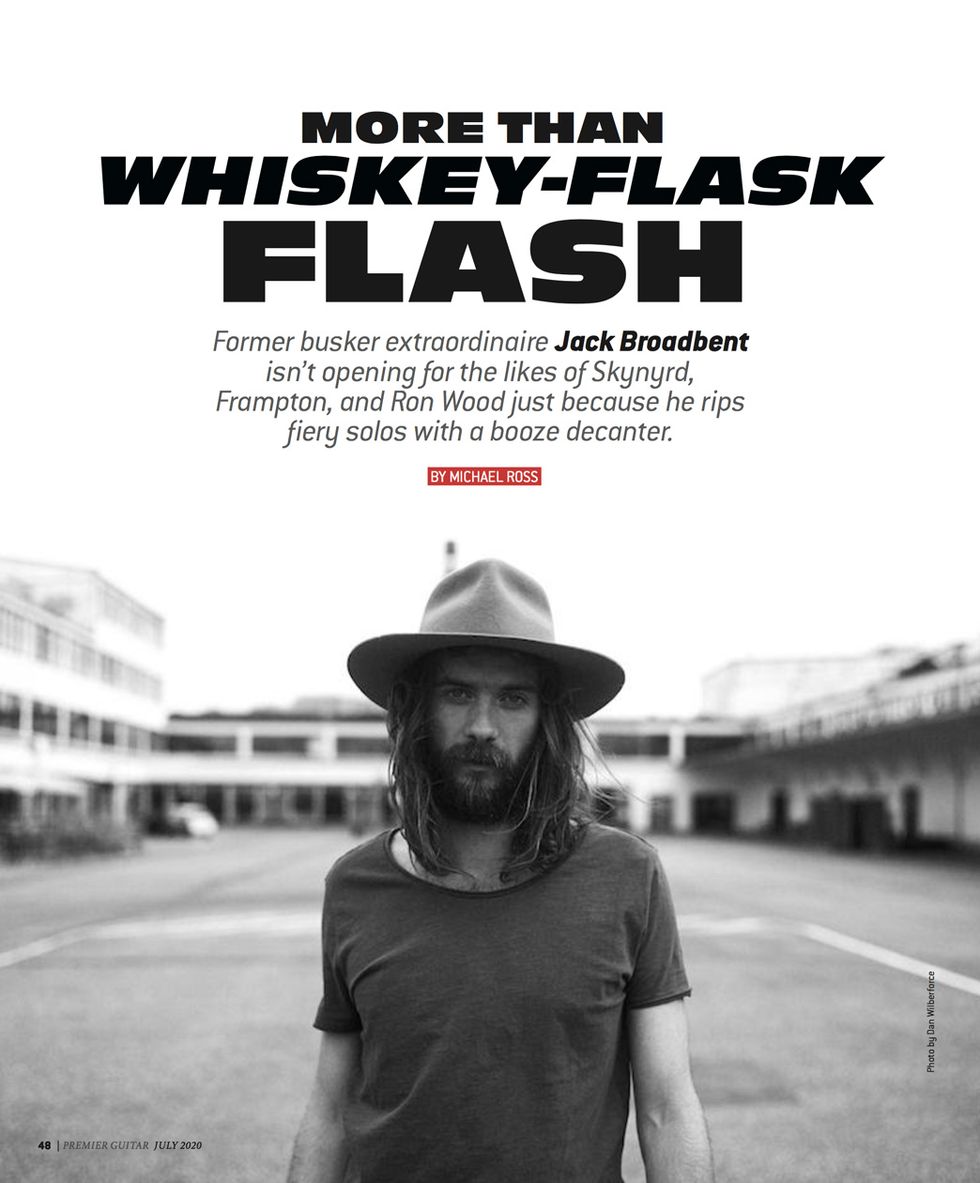

Jack Broadbent, who popped up in Great Britain in the latter part of the 20th century, spent much of his youth busking on the streets of various countries. The seeker appellation fits him nicely too—from his world traveling to his evolution as a guitarist to his perception of the COVID-19 quarantining in effect at the time of this interview as an aid rather than a hindrance to his quest. “I find myself sitting with a guitar in my hand, bursting with ideas,” he says. “I feel happy I’ve got time to experiment more to see what I want to do.”

Born in Lincolnshire, England, Broadbent grew up with plenty of guitars and music in the house. His father, Mickey Broadbent, played bass in the successful power-pop band Bram Tchaikovsky (“Girl of My Dreams”). “Now he plays with me,” Jack says. “We go out as a duo quite often. We were just supporting Ronnie Wood on tour in the U.K.”

Though now known as an exciting blues guitarist, Broadbent initially develop his playing as a means to write songs. “As I gravitated to styles like blues and jazz, I had to pick up more skills,” he explains. “But it was all self-taught, through songwriting.”

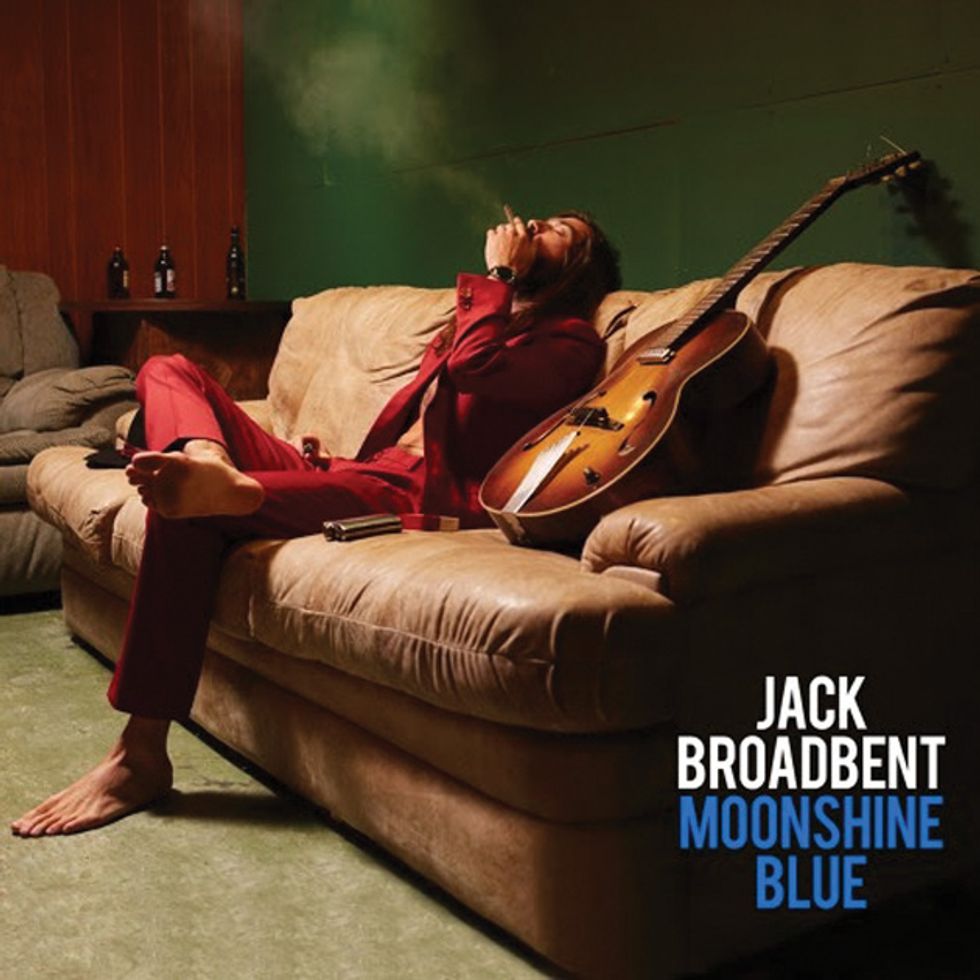

Although it was Broadbent’s flashy boogie playing—including his preference for playing slide with a worn whiskey flask—that excited street audiences for many years, when he moved into clubs and festivals he found a welcoming home for his songwriting. Some songs on his new album, Moonshine Blue, recall ’60s British blues bands like Fleetwood Mac and Savoy Brown, who helped reintroduce Americans to the heritage they had neglected. On other tunes, Broadbent mines the singer-songwriter tradition that burgeoned in the hills around 1970s Los Angeles. Somehow, in the blend of his deft-but-easygoing guitar work and warm, dusty singing, he makes it all work together as a single musical voice.

The story of this seeker’s journey toward musical integration provides an interesting contrast to some of today’s YouTube-to-stardom career trajectories. As storytelling is part of the troubadour’s trade, Broadbent was happy to hold forth.

How did you get into blues?

After my father had been playing rock ’n’ roll for years, he moved back to Lincolnshire and ended up playing in local bands. Around the time I was born, in 1988, there were a lot of R&B and blues bands doing the circuit, so I was brought up on R&B and great local blues. That music was in my head from day one, but I didn’t really include blues in my repertoire until many years later. I played more folk music and rock until I was way into my 20s.

A number of your tunes feature boogie rhythms, which I assume comes from John Lee Hooker.

Absolutely. I am always referencing people like Peter Green and John Lee Hooker.

Did you play in bands with your father or more with people your own age?

I was writing more from a solo perspective. Anything I would write, me and my dad would play together, just for the enjoyment of it. I steered away from the band thing because I didn’t want to sound like everybody else.

Your 2013 album Public Announcement sounds like a band recording.

It’s more of a band sound, but it wasn’t a band. That was me playing all the instruments. I had a house up in the Lake District, and a digital 4-track machine. It was a project that came out of experimentation.

You play drums as well as guitar?

I play everything. When I did play in bands with my father and other people, it was quite frequently as a drummer or bass player. Now that I’m established as a guitar player, I never get a chance to hit the pots and pans, which is a bit of a shame.

When did you start busking?

Around age 21.

Did you move to London to do it?

I predominantly honed the skill in London, and then used to go over to Europe—places like Amsterdam, Berlin, or France. That’s the beauty of busking: It goes with you wherever you go.

Did you prefer busking to joining or putting together a band?

It certainly makes more money. I was doing it to support a lifestyle of writing songs. I was a busker by day and then gigging in clubs by night. Over the years, the stuff I was playing on the street started to infiltrate my club set. Before that it was more on the singer-songwriter side. Now, I like to think I pull it all together under the guise of roots music.

How did the repertoire differ from the streets to the clubs?

On the street, you have a lot more freedom. You haven’t got a time schedule to adhere to. I was playing more finished songs at shows, but then I slowly started to realize I could integrate a little more freestyle playing. I started to bring my slide guitar more onstage rather than just using it as a busking entity.

TIDBIT: For his fourth studio album, Broadbent cut his guitar tracks while being accompanied by his father, Mickey, on bass, and the rest of the instruments were recorded later.

What did busking teach you that translates to indoor gigs and festivals?

It taught me communication between the performer and audience—about breaking down the rubbish barrier of “This is a performance—you watch me. I don’t talk to you. You don’t talk to me.” When busking you can stop any time, have a chat, do whatever you want to do.

What doesn’t translate?

You can’t have a smoke break in between songs [laughs]. On the street, it’s more of a jam. You can rattle around the same tune all day, as long as there’s new people coming past. That’s where I got my 10,000 hours in. If you do something long enough, you get a good feel for it. For me, swinging a blues groove in front of people for a couple of hours every day without fail might not have been a formal lesson, but it all sank in.

Is that how 2103’s The Busking CD was born?

That was to sell whilst busking.

Where did you record it?

In my flat in London.

You’ve developed a style that sounds like you, even as you shift from a flat-out boogie to a sensitive singer-songwriter number. Is it the distinctive sound of your voice that makes it all work?

I suppose that’s the factor that keeps everything together. Like Neil Young and Radiohead, I love to play different styles of music and guitar. I wouldn’t ever want to feel I was pigeonholing myself. The death of creativity would be to say, “from now on, I just play blues, or folk.”

Other than the obvious spectacle factor, what inspired you to use a flask as a lap slide?

It was the closest thing to me at the time, I think.

So, you fell into it from taking a nip before playing?

Playing on the cold streets of England, it’s nice to have some good company in your pocket.

Riding the frets with a well-worn steel whiskey flask, Broadbent flogs his open-D-tuned Hofner Senator. About his choice of slide, Broadbent says, “Playing on the cold streets of England, it’s nice to have some good company in your pocket.” Photo by Justin Brown

What are those distinctive-looking guitars you’re using?

They are both 1965 Hofners. One is a Congress model, the other’s a Senator. The Senator is the one I use for slide guitar. I found them to be very robust. I like the sound and look of them. I’m currently endorsed by Hofner, but I choose to play the older instruments for their tone.

What gauge strings do you use?

I use heavy strings, like .013s on the Senator for slide guitar, and .012s on the Congress. I usually go for D’Addario.

Do you use the same tunings for lap and standard playing?

Generally, I like to play in D, because it suits where my voice sits, but when you’re using open tunings, the simple application of a capo means you’ve got quite a lot of freedom to play in other keys.

Is it full open D—with the 3rd string tuned to F#—or some variation on that?

Open-D [D–A–D–F#–A–D] is the staple, yeah, but I’ve got a couple of hybrids for a few tunes. I like to keep those a little closer to my chest.

What amp do you use when playing on the street?

I haven’t played on the street for about six years now, but when I did I always used a Roland Cube Street. I still do. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. Sometimes, say for recording, I’ll flirt with other things, but because I’ve managed to get a sound together like that, I try not to steer too far away from it. I like that scratchy sound.

Are you using that now at festivals and clubs?

Still using the shanty busking equipment, yeah. I generally DI the amplifier, so I’m using it as a glorified distortion pedal and reverb unit.

In one video, it looked like you were sitting on your amp.

I still do that as homage to where it all kicked off from. It keeps me subconsciously grounded. I run the amp off six AA batteries, which is pretty crazy. When I was opening for Lynyrd Skynyrd, Peter Frampton, and Ronnie Wood, the sound engineers were always going, “You’re going to use batteries?” I’m like, “Yep.” Sometimes you get a little extra saturation and thickness of tone when the batteries start to run down a little.

On Moonshine Blue, is that just you or are you playing with other musicians?

The new record was a little different. Lynyrd Skynyrd’s current piano player, Peter Keys, is playing keys on it. I recorded it at his studio in Nashville. My father plays bass, and it’s me playing percussion. Bruce Cameron, who produced it with me, plays some keyboards as well, and a guy called Mickey Gutierrez plays a saxophone solo on one of the songs.

A lot of times when people usually play solo, it can be hard for them to sync with other musicians.

I played live in the room with my father, and then added the percussion afterwards. All the other pieces came in around that.

The album sounds very intimate.

We close-miked the vocal and the guitars, particularly on the softer material, to get that proximity.

Were you using the Roland amp in the studio?

I definitely used it for the slide guitar parts. This time I wanted the slide guitar to be more an accompanying instrument, rather than always the lead part, so I recorded the bones of the songs on acoustic guitar. I then added the slide around it in the same way I was adding keyboards, just to support the material.

Were you using the Hofner Congress for the acoustic parts?

For some songs I used my Hofner. For others, I used a Gibson L-00, which is like a reissue of the LG-2. I now actually have a 1949 Gibson LG-2 that I just picked up, which will be definitely featured on the next record. It has such a beautiful, clean acoustic tone.

How was the high sustained note at the end of “Moonshine Blue” produced?

I used an EBow and slide.

It sounds like different guitars were used for the rhythm and slide parts.

It was the Hofner Congress, my acoustic guitar for the rhythm part, and then the slide solo was the Senator with amplification.

Guitars

1965 Hofner Congress

1965 Hofner Senator

1949 Gibson LG-2

Gibson L-00

Gibson Melody Maker

Amps & Effects

Roland Cube Street

Strings & Slide

D’Addario .012 and .013 sets

Half-pint whiskey flask

How did you get the distortion on the slide guitar on “The Lucky Ones”?

That is from the Cube.

There’s a filtered background sound on the intro to “Wishing Well.” Is that a keyboard?

That is a reverse guitar. I took a section of the guitar and stuck it in backwards … just classic messing-around studio stuff.

There’s also a distorted guitar behind the acoustic, and a solo that sounds like multiple guitars at the same time.

I used acoustic guitar as the basis, and then used a Gibson Melody Maker to double up the rhythm part and for the solos. I tried to weave the solos off each other. I split them left and right, and let them fight. I wanted them to go off like fireworks. I was recording with a member of Lynyrd Skynyrd, so there was definitely an element of sneaking in that double-threat guitar solo thing.

“The Other Side” has an interesting chord progression—E minor to C minor. What inspired that?

I was experimenting with tunings. That song’s played in a drop-C tuning—essentially open-G but with a low C in the bass. There was something about being able to anchor back to that C that felt nice.

Tunes like “Tonight” and “The Lucky Ones” have a pop feel. Where do those sorts of influences come from?

I love bands like Steely Dan, Little Feat, and the Doobie Brothers. I was listening to all that stuff when I was about 16, so I suppose any hint of a popular music aspect was coming from my love of bands like that. I’ve never been shy of a hook.

There is a very ’70s Laurel Canyon sound to some of the songs on the album.

That comes from my love of the Band, Crosby, Stills & Nash, and Joni Mitchell. All the good stuff.

Was the sparse production influenced by the fact that you knew you’d be going out and playing it solo?

Yeah. I can play the whole record solo acoustic, because all the songs were written solo acoustic. In the studio, it’s more about color and to be able to hear the potential of extra parts.

What’s the plan from here?

I just came off tour all over the States, from Alaska to Florida, from Seattle to L.A., and back up to Chicago. Now, I’m in [coronavirus-mandated] isolation. The next record is written. I was supposed to be going into the studio in the next couple of weeks. Obviously, due to the current situation, that’s having to be pushed forward. It means I’ve got more time now to refine what I was already working on.

Where are you going to record the new album?

I like to record at home studios in nice locations, where I have freedom to not worry too much about how much time I have. The idea was to go and do it in the South of France at my friend’s place. Me and my producer, Bruce Cameron, were going to take some gear down somewhere vibey, old-Rolling-Stones-style. I like to work at night and not a lot of professional studios like you staying up until 5 in the morning.

Not anymore, anyway.

Well, exactly, and you can’t even have a spliff while you’re working.

Flask in hand, Jack Broadbent lays into his slide, lap-style, then flips to conventional roundneck fingerpicking during this February 2020 mini-concert at the Paste Magazine studio in New York City.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.