Chai is a quartet hailing from Japan that sounds like a cross between infectious bubblegum pop and the Gang of Four. At first glance, their Alvin-and-the-Chipmunks-style vocals, choreographed dance moves, matching stage costumes, and obsession with the color pink is not something you’d necessarily expect all readers of Premier Guitar to dig. But trust, twin sisters Mana (lead vocals, keys) and Kana (guitar), Yuuki (bass), and Yuna (drums) can rock.

Want proof? Check out the YouTube Music Series live performance they did in late 2017, of their song “N.E.O.,” from their debut album Pink. It starts out simply enough, with a focus on high-pitched unison vocals and coordinated hand motions, but soon morphs into seriously churning funk, including a tasteful upper-register bass figure and wah-flavored comping—although it’s actually a Phase 90. The song grooves intensely, and that should be enough to pique the interest of serious listeners, but then comes the breakdown at the 1:30 mark, and out of nowhere they bust into borderline apocalyptic, fuzzed-out, post-punk madness.

Punk, the band’s second release, continues in that vein. It’s smiley-faced pop, but below the surface lurks a bevy of driving bass lines and heavy tones. Check out the bass groove and slick R&B fills on “Fashionista” (they farmed out the mix for this track to award-winning U.K. engineer Marta Salogni), or the crushing, phased power chords in the middle of the album opener, “Choose Go!” Even a synth-heavy song like “Curly Adventure” is propelled by a throbbing bass part—a constant throughout Punk’s 10 songs—and the guitar work is tasteful and precise. Their songwriting is tight, and slick millennial Top 40 informs their overall aesthetic, but they’re a guitar band at heart.

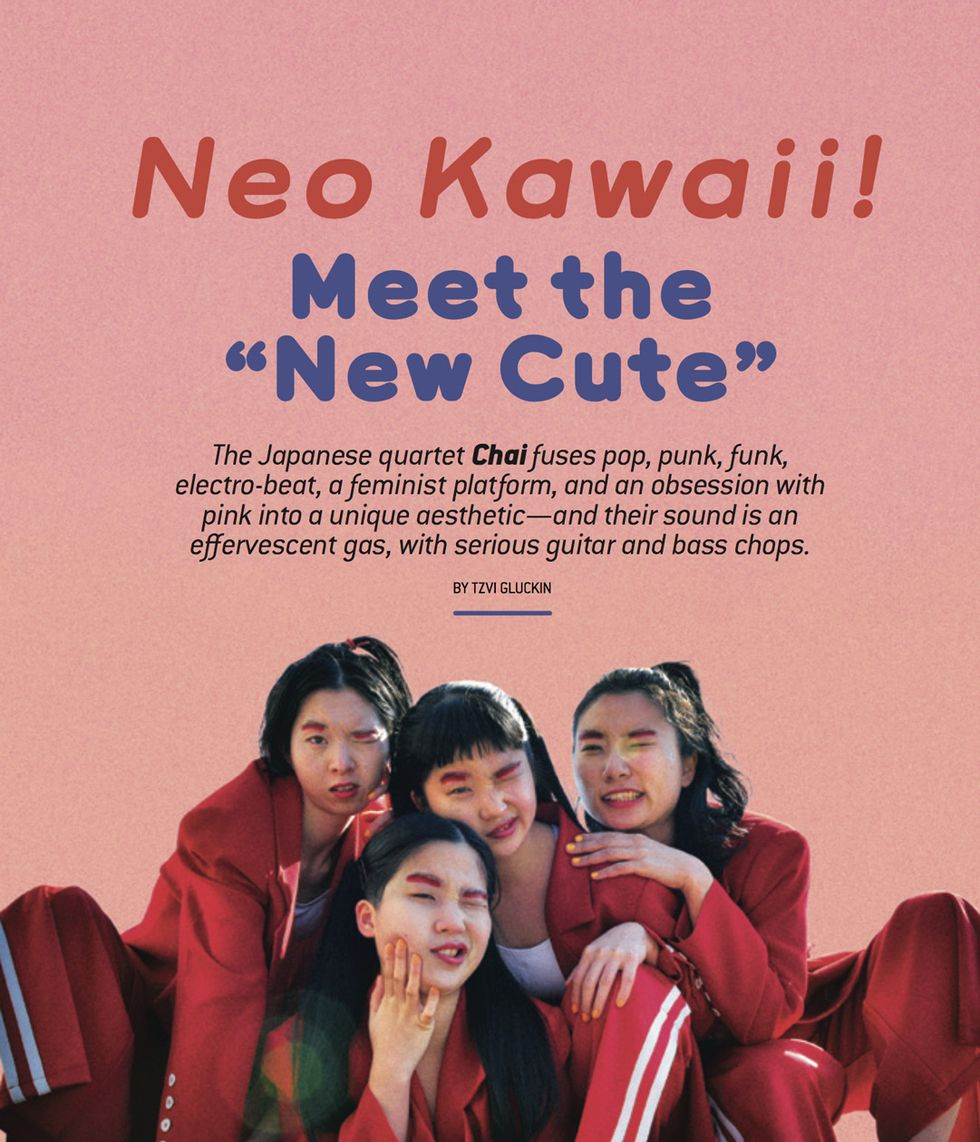

Chai’s idiosyncratic vocal stylings are intentional, and part of a broader cultural statement they’ve labeled “neo kawaii” in Japanese, which loosely translates as “new cute.” That concept—at least in terms of how it’s meant in Japan—parallels with Western feminist notions of self-esteem and positive body image.

“Everyone has insecurities,” the band explains by way of their translator, Rena Tyner. [Editor: Due to a language barrier and the use of a translator, it was sometimes unclear which band member was speaking during this interview.] “The concept is that, in Japan, they have a set beauty standard, which is called, ‘cute.’ Growing up, we didn’t feel like we fit into that, so we created a ‘new cute.’ Anybody who doesn’t fit into what society calls cute—anybody who doesn’t fit into what society says is attractive—can be neo kawaii. It doesn’t matter if you fit into those standards or not; we should all be considered ‘cute.’”

But cultural statements notwithstanding, our focus is music, and for that, Chai more than delivers. They’re tight and can stop on a dime, and seem to interact with each other on an almost telepathic level. (It doesn’t hurt that lead singer Mana and guitarist Kana are identical twins.) Chai’s attitude is loose and improvisatory, but they keep that contained within fixed arrangements and strong songwriting.

Chai was founded in Nagoya, Japan, a city between Tokyo and Osaka, in 2012. The band members grew up listening to J-Pop, which is homegrown Japanese pop music. They liked acts like Tokyo Jihen—a somewhat jazzy-sounding group fronted by vocalist Ringo Sheena—and the popular singer Aiko. As they got older, they became obsessed with Western bands like Basement Jaxx, Justice, Devo, and Brazilian indie-electro-rockers CSS (Cansei de Ser Sexy), which proved transformative. The influence of the latter’s bubbly aesthetic and blend of rock and synth-pop seems especially apparent in Chai.

“Most of our songs, we take from other bands as an influence, but try to imagine what we would do if we were that band,” Chai say. “This is the sound we would portray if we were that band.”

TIDBIT: Although the band recorded their second full-length album in Tokyo, they farmed out the mixes for key tracks “Fashionista” and “Curly Adventure” to top-flight mixing engineers Marta Salogni and Daniel Schlett, respectively.

Kana is Chai’s guitarist. She took piano lessons as a child and that remained her principle instrument into high school. That changed after she, her sister Mana, and Yuna, the band’s drummer, joined a music club in school, where Kana began learning guitar and the three girls came up the musical curve by performing J-Pop covers. “It was kind of like a glee club, but for music,” Kana says. “The teacher who ran the club was a guitarist and I watched him and learned from him. He basically taught me how to read music.” But becoming a guitarist professionally was almost an afterthought, even though it became her main instrument when they started the band.

Yuuki first started playing bass when she joined Chai, which, given her level of proficiency, is remarkable. “I did a little bit of piano when I was in preschool—very young, 4 or 5 years old—and didn’t do it after that,” she says. “I didn’t touch an instrument again until Chai in 2015.”

The group’s debut EP, Hottaraka Series, was released that year, which followed a string of singles and even a 2013 tour of Japan. From the outset, Chai was song-centric, and their rehearsals, even early on, were never jam sessions. Mana came up with melodies, and those melodies were the kernels that blossomed into songs. “The band pretty much started with original music,” Tyner says. “The concept for the band came later on, gradually, but originally it came from Mana’s melodies. She said, ‘Let’s work on this and make it something original.’ And it bloomed from there.”

Over time, that process became more groove oriented. When composing songs, Kana or Mana usually have a rhythm in mind, which they discuss with Yuna. They work with that groove and come up with an arrangement or outline of a song. “Once they have that, Mana sings on her own and decides how she wants it to sound chorus-wise, and Kana figures out the melody,” Tyner adds. “They do the lyrics last.”

“I just play by ear,” Yuuki explains in reference to her bass parts. “Or whatever the girls tell me to do. In general, I don’t think I have a style. Like with my slapping, I don’t have a ‘technique,’ I go by feeling.”

Kana’s instrument of choice is a Gibson ES-335, which she puts through the paces via intensive pop, rock, and funk chops, enhanced by basic overdrive and modulation pedals. Photo by Sara Amroussi-Gilissen

Their songwriting is genre-elastic as well. For example, “Boyz Seco Men,” from Pink, incorporates funk comping, heavy metal crunch, and dissonant keyboard stabs. Although they claim that diversity isn’t intentional.

“It’s not really on purpose,” Chai says. “For ‘Boyz Seco Men’ in particular, we were influenced by CSS and Red Hot Chili Peppers. It was a mixture of those two. We wanted to rock out like a Red Hot Chili Pepper, but at the same time have that CSS melody. It isn’t necessarily planned, but more like, ‘We like these two sounds, let’s see how we can make it work together.’”

That organic approach applies to their arranging and production as well. “Everything is pretty much natural, go with the flow,” they add. “We don’t want to be stuck in one genre, so we try to take different elements of what we’re influenced by, put it together, and somehow make it work. It’s a bunch of different ingredients that we throw in a pot, and whatever comes out, comes out. That’s how Yuuki writes our lyrics, too.”

Guitars

Gibson ES-335

Amps

Fender Hot Rod Deville ML 212

Effects

Ibanez TS808DX Tube Screamer Overdrive Pro

Boss DS-2 Turbo Distortion

MXR Phase 90

Electro-Harmonix Holy Grail Neo Reverb

Boss CH-1 Super Chorus

Korg Pitchblack Mini Tuner

CAJ AC/DC Station IV Power Supply

Strings and Picks

D’Addario Nickel Wound (.010–.046)

Custom picks

Basses

Fender Precision

Amps

Ibanez Promethean head

Effects

None

Strings and Picks

D’Addario Nickel Wound (.045–.100)

A stock Gibson ES-335 is pretty much all Kana uses with Chai. “I like the Gibson for the look and the sound,” she says. “I bought it on my own and I don’t play another guitar. The label gave me a Stratocaster, but mainly I stick to the Gibson.” She uses a modest pedalboard that gives her multiple gain stages and minimal modulation, and she plugs into a Michael Landau signature Fender Hot Rod Deville. Although, when touring anywhere other than Japan, the band always rents amps.

Chai’s recorded output sounds polished and tight, although they insist their approach to recording is as laid-back and direct as their songwriting. Most of the tracking is done live, and they try to record in full takes. “We do about five or six takes per song and we can usually get it done in one shot,” they say. “We always play the songs straight through, without stopping. Although when it comes to the vocals, we overdub those later.”

Punk, the follow-up to Chai’s 2017 debut album, Pink, was recorded in Tokyo at Studio Somewhere. It’s a small place and they chose it because of its relaxed vibe. “It’s not a famous studio,” they say. “Other famous musicians haven’t recorded there, but we like it because it has a really good home feel.”

Most of the album was mixed in Tokyo, too, by Shu Imamoto, who also engineered the sessions. The band worked on a few tracks with bigger-name Western engineers to add contrast and color. “Fashionista” mixer Marta Salogni has worked with Björk, Frank Ocean, and Holly Herndon, for example, and for “Curly Adventure” they brought in Brooklyn-based engineer Daniel Schlett (Ghostface Killah, Steve Gunn, DIIV).

Chai is particular about their live sound, and even in smaller venues they spend a lot of time at soundcheck. “Last September we opened for Superorganism in the U.K. and only got about 30 minutes,” they say. “But we started doing headlining shows in the U.S. last year and can now spend over an hour in soundcheck.” Although when playing showcases, like at South by Southwest, that type of focus isn’t possible. “When we have a time constraint, we play Daft Punk’s ‘Get Lucky’—except that we call it, ‘Soundcheck Lucky.’ If we can do that song perfectly, then we know we can do everything else right. That’s our go-to soundcheck song for when there’s no time.”

The band has been playing stages throughout Europe and the U.S., and the reaction has been consistently positive. “The only place that’s different is Japan,” they say. “American people are so warm and welcoming, they just scream even if they don’t know us at all. We love that about America’s energy. In the U.K., we were the opening act, which could have played a part, so at first they were a little quiet, but eventually they go crazy and wild, too. But in Japan, most people just listen. They watch and they all do the same hand movement—that fist pump, ‘Jersey Shore’ thing. We want to see them enjoy it, which is what we like about American audiences. People dance if they want to dance and do whatever they want to do.” Nonetheless, Japan remains their stronghold, in large part due to the video for “N.E.O.,” which was a viral sensation in the island nation.

Yuuki plays a Fender P bass and is a major part of Chai’s propulsive, percolating sound, laying down core riffs and exploring funk and R&B textures. Photo by Sara Amroussi-Gilissen

When Chai played South by Southwest for the third time this spring, they followed that gig with a string of U.S. dates. They return to the States in July to play the Pitchfork Music Festival in Chicago. They’re signed to Sony in Japan, although their albums are released in the U.S. by the indie label Burger Records, who were intrigued after seeing Chai’s epic video for “Boyz Seco Men,” which is campy and strongly channels Devo.

With killer chops, an original and recombinant musical personality, and a flair for the visual, Chai is a complete package. Their image is hyperactive and positive, their message is important, and their musicality first-rate. For serious music nerds, they’re a secret hiding in plain sight.

With matching traffic cone hats and uniforms, Chai’s video for “Boyz Seco Men” visually channels Devo, but the arrangement is an interesting mash-up of punk, funk, and pop, with flashes of grinding guitar and popping bass.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)