Here’s a question that comes up every once in a while during an interview: “Are there any guitarists you count as influences who might not be as familiar to our readers (or listeners) as more household names such as Van Halen, Hendrix, or Metheny?” My first answer, for quite some time now, has been the same: Jimmy Herring.

Although he isn’t the first to bridge the gap between high-energy rock soloing and jazz-inspired improvisation (the ’70s recordings of Jeff Beck as well as those of drummer Billy Cobham, featuring the late guitarist Tommy Bolin, come to mind), no one to my knowledge has taken it to the level that Jimmy has. If you’re someone who enjoys the “screaming” of rock and blues solos, but has grown tired of hearing predictable pentatonic patterns, or if you’ve ever been intrigued by modern improvisation—chromatic lines, extended triads, outside phrases—but have had to adjust your tastes to accommodate the mellifluousness of traditional jazz guitar tone, then Jimmy Herring might be, depending on your theological juxtaposition:

A. The answer to your prayers.

B. An evolutionary milestone.

C. The embodiment of the term “best of both worlds.”

I first became aware of Jimmy, who was born in Fayetteville, North Carolina, in the early ’90s after an encounter with the great keyboardist T Lavitz (who sadly passed away in 2010). T was best known for his work with the pioneering Southern fusion band, Dixie Dregs, with whom he’d played alongside the virtuoso guitarist Steve Morse (currently of Deep Purple). T had mentioned this fantastic new guitarist I must check out from an Atlanta-based band with a strange name: The Aquarium Rescue Unit. “Aquarium what?” I’d replied, writing it down. (Note: when Steve Morse’s bandmate recommends a guitarist, you listen.)

a Les Paul."

With help from the friendly owner of a newly opened record store in Berkeley called Amoeba (their flagship store, before the now famous San Francisco and Hollywood locations), I managed to track down used copies of the band’s two hard-to-find albums: the eponymous live debut, Col. Bruce Hampton & The Aquarium Rescue Unit, and their studio follow up, Mirrors of Embarrassment.

These purchases would be invaluable. I’d never heard guitar solos developed like this before, played to music that was highly sophisticated yet fun and grooving—not just for fans of technical proficiency. In addition to Jimmy, there was Oteil Burbridge, who blended the bass skills of Jaco Pastorius with George Benson-like vocal scatting, and Matt Mundy, whose mandolin sounded as though he was channeling the harmonic density of saxophonist Michael Brecker. No territory was off limits. Rock, funk, gospel, bluegrass, country, and more were handled with flawless ability and reverence for each genre, all fronted by a slightly elder statesman from the Woodstock generation. Col. Bruce was no virtuoso, but his highly creative wordplay and quirkiness formed the perfect countercultural counterpart to the young wizards. Live, they were mind-altering—an experience matched only by walking in during a sound check in San Francisco and having Jimmy jump down from the stage with a hand extended, a genuine smile, and a “Nice to meet you!” To this day, he holds my title of “Nicest Guy in the Guitar Community.”

Discovering Jimmy and ARU, while musically intoxicating, was also sobering. It shed light on a difficult truth of the business of music and the arts in general: talent is no guarantee of success. It was hard to witness a band so undeniably good (and such nice folks, to boot) be subject to poor distribution, years of endless van touring, and virtually no luck breaking into higher levels of the music industry. Big names of the jam world, including Phish, Dave Mathews, Bruce Hornsby, and Blues Traveler, did what they could do. They took ARU on tour and nudged their respective record labels, to no avail. Meanwhile, one of ARU’s tunes, “No Egos Underwater,” was picked by bandleader Branford Marsalis for the repertoire of NBC’s The Tonight Show with Jay Leno, while another ARU fan, actor and director Billy Bob Thornton, cast Col. Bruce in his Academy Award winning breakthrough film, Sling Blade.

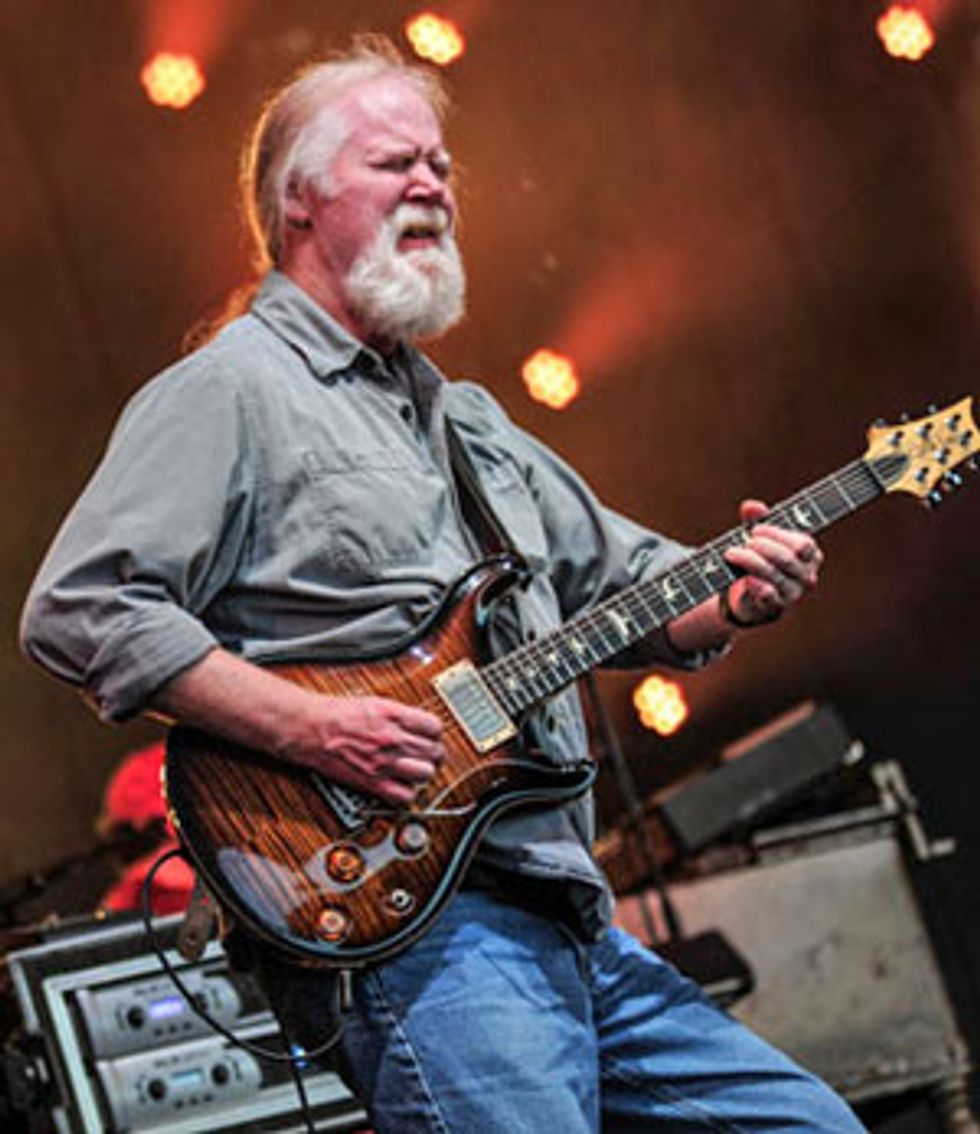

For the majority of Street Dogs, Herring simply relied on a Hughes & Kettner Tube Factor, an Eventide Space, and—for one song—a Vox wah. Photo by Andy Tennille

The good news is that Jimmy would find some fabulous outlets for putting his skills to use, including a tour with the Allman Brothers (which then had Oteil as their permanent bassist), Billy Cobham and T Lavitz’s Jazz is Dead, the Grateful Dead’s Phil Lesh, and, since 2006, one of jam’s biggest groups, Widespread Panic. Their latest album, Street Dogs, features terrific songs and live jams, with Jimmy boldly venturing into some new territory.

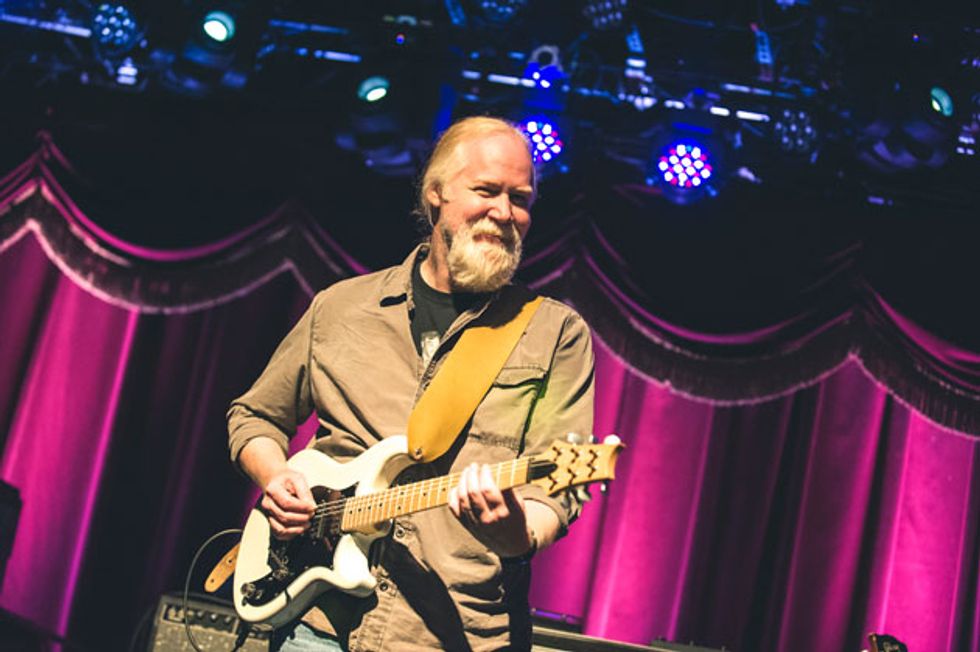

Meanwhile, ARU recently embarked on their first extensive reunion tour in honor of—oddly enough—their 26th anniversary (Col. Bruce’s idea). The tour wrapped up at the Brooklyn Bowl, close to my home, and I was grateful it fell on a rare day I was off tour. Jimmy and the guys sounded as good as ever, and afterwards he and I had a great hang. A few days before, we’d been able to reconnect and discuss all of the above and much, much more.

Jimmy Herring’s story is an amazing one, with tales of guitar artistry, adventure, inspiration, and many memorable characters encountered along the way. I’m grateful for the opportunity to share this in-depth conversation with my friend Jimmy, one of the nicest guys I know—who just happens to be one of our true treasures of modern guitar playing.

“Music school is not real big on Bruce’s list of good things. He felt like it was necessary to wipe away all traces of music school, because he felt like ‘music school’ was an oxymoron,” says Herring about his ARU bandmate, Col. Bruce Hampton. Photo by Vikas Nambiar

You were one of the first guys I heard that had a rock tone combined with an expansive harmonic sensibility.

When I went to GIT [Los Angeles’ Guitar Institute of Technology] in ’84, I heard Scott Henderson on the first day. It was like [saxophonist] Michael Brecker meets Jeff Beck. I was like, “What the hell is this?” It was the delivery of a rock player but harmonically deep with all these incredible lines. It was an eye-opening experience and really messed me up. It changed my whole way of thinking.

What Brecker albums did you get into?

Heavy Metal Bebop was the first. I had a friend who played me that even before I left for California in ’84. It must have been about ’80 or ’81 when I first heard him, and he had that envelope filter on his sax and was playing these insane lines. That definitely was an influence already without lifting any lines, just by listening to it. When I first started playing with Bruce [Hampton] we were listening to a lot of Coltrane and his stuff where he stretched out and just played on vamps. All that stuff started to come together during that time. You came out to a show around then, right?

Yeah, it was at the Great American Music Hall in San Francisco. I think Bruce couldn’t make it so you did an instrumental show with Oteil picking up some vocals. My friends and I still thought it was one of the best shows we’d ever seen.

Oh man, thanks. During that era we were touring a lot and Bruce was getting real tired of touring. Honestly, there were some other things he was tired of, too, like the management we had at the time. It was starting to get bigger than he wanted it to be. I remember you said in print one time, “Well, there’s all these jam bands, but there’s this one that seems different from the rest of them.” It cracked me up, because when we started playing our band was really just an experimental thing that happened in Atlanta one night a week.Then one night these cats walked in and heard us and invited us to open for them. It was Widespread Panic. We didn’t even know who they were. We became friends with them and opened a couple of shows. They were just the nicest cats ever.

How much of a local or regional following did they have back then?

They had this subculture thing going, and even in 1989 they could sell out three nights at Center Stage in Atlanta, which was about a thousand seats. We thought, “Holy crap! These guys are rock stars.” Finally, Bruce would let us tour. He was like, “You can’t handle touring [laughs]. You’d be crying for your mommy in the first week.” We all got a great laugh out of that one. He’s just an incredible cat to learn from. In our process of touring with Widespread, we met Dave Matthews, Phish, and Blues Traveler. Then, for lack of a better term, this jam-band renaissance of sorts was starting to form and they put the H.O.R.D.E tour together, but the powers that be did not want us to be a part of it.

Why do think that was? Because you were too musical?

That’s funny [laughing]. I would put it more like we didn’t have any drawing power. And we aren’t really made for playing outside in the afternoon. We’re a club band that goes on at midnight. The other bands went to the management of the festival and went, “They’re going to be here. And if you don’t like it, we aren’t going to be here.”

I remember calling you one time because we had gotten to know each other a little bit and I was in a real tough spot. Bruce quit the band and it was falling apart, so I was looking for guitar tech jobs. I needed a job to feed my family and I remember calling you for a tech job. Do you remember that?

Wow. I know we had crossed paths, or just missed each other at one point. I don’t remember that being what it was about. That’s astounding. There are stories about jazz piano legend McCoy Tyner getting a gig as a cab driver in the ’70s. Which is insane.

Aw man. That’s just … I can’t believe that.

Jimmy Herring’s Gear

GuitarsCustom PRS w/Lollar Imperial pickups (circa 2000)

American Deluxe Fender Stratocaster (circa 2008)

1969 Fender Stratocaster

Baxendale steel-string acoustic

Amps

1964 Fender Super Reverb rehoused in a Mojotone head

Mojotone 4x10 cab with Tone Tubby Alnico speakers

1964 Fender “Tuxedo” Bassman

Germino Lead 55

Early ’70s Ampeg B4

Open-back Tone Tubby 4x12 cab

Effects

Hughes & Kettner Tube Factor

Eventide Space Reverb

Ernie Ball Volume Pedal

Vox V847 Wah

Strings and Picks

D’Addario (.010–.046)

V Picks Large Pointed Lites

Stories like that were big lessons for me, in a way—that talent matters, but it doesn’t matter. It’s the most important thing, and it’s not the most important thing. It has so much to do with circumstance, popular trends, and business. Luckily, you didn’t have to tech and you found a good gig, right?

My next gig after that was Jazz Is Dead. We also did this little side project with Butch Trucks from the Allman Brothers called Frogwings. I remember Butch asking me if I knew any bass players [laughs]. “Yeah, I know a really, really great bass player.” I’d sat in with Derek Trucks on a tour and Butch came to a show and said, “I like the way you two guys play together. I want to put a band together.” Oteil and I went down to rehearse with Butch’s new band, which was going to have Derek in it. We had fun with that and did a little two-week tour, and they recorded it to put a low-budget record out.

It was so hard to get that first ARU album. That’s an unfortunate thing, but it’s been very influential. ARU is now doing a reunion tour. What took so long?

It’s mostly scheduling, as you can imagine, with everyone doing different things and being in bands that tour a lot, it was hard to get it together. But Bruce would call sometimes and go, “What are you doing this week? You’re home! I know you’re home!” He knows what our schedules are. He knows everything.

I saw his “outstructional” guitar video. [Editor–A bizarre film called Outside Out, directed by Phish’s Mike Gordon.] He knows what you’re thinking [laughs].

He’s so crazy. Last year we were going to try and do it because it was the 25th anniversary, but scheduling made it impossible. So I said, “Let’s try and do the 26th year.” Because if you know Bruce, he never says, “Meet me at noon.” It’s always, “Meet me at 11:52.” So we all kinda laughed and thought a 26th anniversary tour made sense. It’s been tough because I just had a five- or six-week tour with Panic and then four days home before this run took off. But, man, I’d do anything to get back and play with these guys again, because it’s such a special thing.

I think it brings out a different side of you as well.

Oh, it does. Really, strangely, I got out of school in ’85 and I had never been in a true touring band. I moved to Atlanta in ’86 and by ’89 I was still in Atlanta and just got into Bruce’s band. I didn’t even know how to play normal music, really. I mean, I did, but I didn’t have any touring experience to speak of. Music school is not real big on Bruce’s list of good things. He felt like it was necessary to wipe away all traces of music school because he felt like “music school” was an oxymoron [laughs]. I mean, he’s really just kidding. A lot of it’s in jest, but he understood our minds.

I’m sure there’s a lot to be learned from that, because some things do need to be unlearned. Of course, there are exceptions. Some guys come out of music school on their way to becoming fully developed artists, but there are a disproportionate amount of “cookie cutter” players. It seems like when you went to the Musicians Institute it was a great time to go there. Dude. It was right on the cusp. I was lucky.

Herring’s main gig is lead guitarist in the seminal Southern-rock jam band, Widespread Panic, where he splits guitar duties with founder and frontman John “JB” Bell. Photo by Andy Tennille

Who else was there with you? Weren’t you there at the same time as Jeff Buckley?

Jeff was, like, my best friend. We were practically inseparable. Paul Gilbert was there, too. I remember seeing Paul on the first day of school. I was walking down the hall, didn’t know anybody yet, and there’s this practice room with a group of people huddled around. You can’t even see exactly what’s going on. I peeked over the top and there was Paul sitting in a chair playing. He didn’t even have his guitar plugged in and you could have heard a pin drop. He was playing all that Yngwie stuff from [Alcatrazz’s] No Parole from Rock ‘n’ Roll album note for note. Without an amp! His picking hand was like a jackhammer. He just knocked all of us right on our asses.

Buckley is an artist of such depth that many would be surprised to know that he went to Hollywood’s top guitar school, where all the shredders go.

He was only 17 and I was 22. We were in ear training class together and quickly realized that we had to get together. He would come over to my little apartment and even though he had his own place he stayed at our place more than he went home. I’ll tell you something about him: That cat had the best ear of anybody I have ever been around. This was before the days of being able to digitally slow down Coltrane solos.This cat transcribed all these Coltrane solos, all this stuff from Steve Vai’s Flex-able album, Dregs stuff, Alan Holdsworth solos—you name it. It was inspirational. I was trying to do the same thing, but he was the first guy I met who was as into it as I was—but he was much further along.

What was he like as a player?

He was incredible, but he was real shy. He didn’t play a lot around school, though. He had this electric Ovation guitar. One of the rare ones, I think it was called the Breadwinner. It looked like a broken egg. It wasn’t a great guitar, but it was what he had and he made it work. At graduation he put together a trio and performed a Weather Report song that didn’t even have guitar on it. That will tell you something about his abilities. He never even sang in front of me except when we would do ear training. We would start with a tone and he would sing an interval and I’d have to say what it was. Then I would sing the note he sang and then sing another interval from that note. He was just phenomenal.

I can hear Steve Morse’s influence in your playing. Coincidentally, I first heard of you through T Lavitz, who played in the Dregs. When did you first hear them?

When I was a kid, the Dregs and Steve Morse were a huge, life-changing experience for me. And not just because I was young, but because I got to see them a bunch of times. They toured incessantly and seemed to be in North Carolina a lot. I bet I saw them 100 times. I was like a Deadhead that followed them around, so they joked that I was a “Dreghead.” I would drop anything I was doing if they were close by. Steve was such an amazing role model because this cat didn’t party; he had his guitar with him all the time, and was legendary for practicing for three hours after the gig. It was a tremendous impact on my young way of looking at things and I wanted to do that. So no partying after the gigs—just straight to the hotel and take my guitar into the bathroom where there’s reverb [laughs].

The first guitar clinic I ever attended was at Leo’s Music in Oakland. I had only been playing a year or two and just stopped in to pick up something. Turns out it was Steve Morse. It was a great way to get introduced to him and the Dregs.

I had started to see them when I was a junior in high school. I would be at sound check just because I wanted to see this band every minute I could even if they weren’t playing. I got to be friends with the road crew and they started calling me “North Carolina” because every time they played in the state I was there. I got to be friends with them enough that they would let me start to help set up the gear. T would seem really approachable. I’d go up and ask him to show me a passage in “I’m Freaking Out” or “Odyssey.” He was kinda struck that this little kid knew these songs by name. T would separate the parts and show them to me slowly.

YouTube It

The “Santana at Woodstock vibe” described by Alex Skolnick propels Widespread Panic’s “Cease Fire,” played here during a March 20, 2015 show at the Fox Theater in Oakland, California. The song is a showcase for Jimmy Herring’s fat, silken tone. He drops into his first solo at 2:12, glides into a second, lengthier guitar break—which includes some elegant microtonal bends—at 3:30, and rips like Carlos at 5:12.

Did you ever get to jam with them during this time?

Eventually. Some of the people at the clubs knew me and would tell the crew, “Hey, that kid can play Dregs stuff,” and I was like, “No! Shut up, don’t tell them that!” One night they were all having a party at my friend’s house and they were playing a Dregs album. My friend was telling a crew guy, “This dude can play that tune.” The crew guy said, “You can’t play that.” And I went, “No, you’re right. I can’t play it.” But my friend, who knew I could, was like, “Pick up that fucking guitar and play it!” It was “Pride O’ the Farm” and I had been shedding on it, and so he basically cornered me. So the record was playing and there was a little amp, and I just doinked around with the record. The guy I had given a ride to said, “Next time we’re in town, bring your guitar. You got to go play with Steve.” Of course, I was terrified.

What happened the next time they came to town?

I had my guitar in the trunk of my car and the crew told me to go get it about a half-hour before the Dregs were going on. They instructed me to go in the dressing room where the band members were warming up and hanging out. Rod Morgenstein had a practice pad, T had a small keyboard, and Steve was warming up through a tiny practice amp. Steve unplugged his guitar and handed me the cord. I was trembling! I didn’t know what to do, so I just started playing fragments of Dregs music I had tried to learn, and asking him if I had it right. He was so genuine and kind, and told me “Almost!” T and Rod started playing along with me, and made me feel welcome and encouraged me, but I didn’t get to play with them that night. Years later ARU opened for the Dregs a few times and Steve sat in with us at least once. I was thrilled and, again, scared to death!

Recently, at PRS Guitars’ 30th Anniversary, fusion master John McLaughlin sat in with Herring and The Aquarium Rescue Unit for a set of inspired, spaced-out jams. Photo by Vikas Nambiar

Overall, your tone on the new Widespread record, Street Dogs, is amazing. Who produced the album and what did he do to capture your sound?

John Keane produced it. He’s done a lot of records for this band over the years. He’s just a great producer. He did my last record, too. He’s brilliant at capturing guitar sounds and usually he makes you play through amps that he prefers. On our previous album, Dirty Side Down, I used a 100-watt Fuchs Overdrive Supreme and the Fender Super Reverb. Luckily, on this record he really liked my amps. I’ve spent years tweaking these amps, but he knows where to put the mics. I’ve been into amps that only have one channel, and using just use an overdrive box and my volume knob.

Was the intention for “Cease Fire” to emulate a Santana at Woodstock vibe?

You’re not the first person to say that. That tune was lying around and I’ve had those chord changes for a long time. The group liked it and we arranged it and put vocals on it. It’s kind of classical in a way. Some of the chord changes … like when you build a diminished triad on the II chord and play it over a pedal tone of the root. There’s that one passage [sings], and then it descends in different inversions. But it’s the same two chords every time. You hear that in classical music sometimes. It’s fun to play over because it’s visiting that harmonic minor or Phrygian thing. When we play it live I haven’t used a Strat on it, but I used a Strat and the Bassman in the studio when we recorded it.

What Strat did you use?

It’s an American Deluxe that they made with the neck specs that I asked for—a 12” radius with big frets. I play it a lot. It’s got those noiseless Fender pickups in it that everyone hates [laughs]. Including me! Except when I plug this one in I can’t find anything wrong with it. I did a lot of single-coil Strat stuff on this record for some reason.

How does Widespread Panic gear up for an album cycle? What makes Street Dogs different?

Normally, we would just go in and get a good drum track, which a lot of rock ‘n’ roll bands do. Then start building from that point. But this time we really wanted to try and capture it live. The band made a decision that we were going to do as few overdubs as possible. We had been writing some tunes and some covers were hanging around from the live shows, so we went in the studio in January 2013 to write some tunes. We played them live for a while and came back in January of ’14 to make a record. It wasn’t like we could set up like we were playing live, but they found a way to make it work. I hate headphones. I just can’t make it happen. Depending on what’s expected… but if I’m improvising solos, forget it.

You’re such a dynamic player. It must be hard to get that sense of feedback and control without being close to your amp.

Yeah, man. I have to be standing next to my amp in order to get any kind of relationship between the pickups and the amplifier. It may be superstition talking, but I feel like your amp sounds different when you’re standing next to it. Even if you’re not holding a note and bringing feedback into the equation, I just think it sounds different.

How did you get around that in the studio?

They set the drums up like you would imagine, and then they set the percussion up next to them with a little wall for some separation. JB’s amp was in an iso chamber—he doesn’t suffer from my disease of having to be right by an amp. My amps became really interesting. A lot of the album was done on a ’64 Fender Bassman. You know those blonde Bassmans that Brian Setzer uses? It’s like that except it’s a blackface model, but internally the same as what Setzer uses. It’s a transitional model, from when they were going from the blonde era to the blackface era. They call those “tuxedo” Bassmans. I love that amp and ran it through a 4x12 Tone Tubby cabinet that had four alnico speakers with an open back. My Super Reverb went through another 4x12 in stereo—just like I do live. I had an Ampeg B4 there and a Germino Lead 55.

This was the interesting part: Instead of wearing headphones, the producer brought in a small PA system. He set up the PA facing me. I was in the same room as everybody, but they put up these little isolation walls around me. He basically set that as my monitor mix so I could control the levels of everything. I was able to play just like I was playing a show. My concern was that my amps were behind me and the PA was facing me and going right towards the mics on my amplifier. I thought it would be a bleed problem, but the producer said, “Yeah, you’d be surprised. It’s minimal.” There were probably one or two things on the album where I overdubbed the solo again later, but not because they wanted me to. I just begged [laughs]. They were like, “Don’t re-do that, just leave it.” And I was like, “OK.” As a result I haven’t really wanted to hear it, so I haven’t heard it since it’s been mixed and mastered.

—Jimmy Herring

The album has that single-coil twang to it.

It has taken me years to tweak these amps to make them optimum for both humbuckers and single-coils. I’ve found ways of doing things. Like the right tubes. You just got to pay for them, that’s all. It’s sad that they cost that much, but old-stock preamp tubes are just the best. You know the deal. It makes a huge difference to me. Especially if you don’t use a lot of gadgetry going into the amp. That’s when you really hear the difference with the old-stock tubes. I fought it for years and said, “I’m not paying $95 for an AX7. That’s just stupid.” But man, when I heard the difference I couldn’t deny it anymore.

How do you balance your rig when moving from single-coils to humbuckers?

The most important thing, mainly with blackface Fenders, is you just have to turn it up to at least 8 or it’s going to sound brittle—especially with single-coils. You can’t be afraid of the treble knob. I was always afraid of it. One time I was playing a gig with Derek Trucks. He sounds like the pearly gates open every time he plays a note.

And with no effects! I got to watch him up close at an Allman Brothers rehearsal and it was just incredible.

Yeah. It’s ridiculous. He’s been my tone muse ever since I’ve known him. We were at sound check and I got my Super Reverb set up next to his. I was like, “Man, why is your Super Reverb so much louder than mine?” I know part of that is the fact that he plays slide with higher action. It projects better. And none of my guitars have super-low action, but I’m not a slide player, so it’s not like a Dobro. Derek looks at my settings and goes, “Do this.” He cranked the volume and treble to 10, the mid down to about 4, and the bass off. That’s the key. Either turn the bass down or off. Now, we’re talking about Fender blackface amps; it’s not going to be the same with every amp. I found out later that’s what Jeff Beck does. But it doesn’t work unless the amp is cranked.

When you’re talking about varying outputs of pickups, how do you balance that? With your hands and volume knob?

My volume knob is mostly maxed out, so I just live with a little bit less volume with single-coils. One way I’ve found around that is just use lower-output humbuckers. Lollar Imperial pickups are what I usually use for humbuckers. They have a low-wind Imperial, and I recently put those in a guitar and they are great. They have that creaminess when you crank the guitar volume, but when you back off, believe it or not, they sound like a beefed-up Tele. A good Les Paul, we’re talking about the late ’50s, sounds like a Tele on steroids. That’s why you see those old cats playing funk on a Les Paul. A lot of those old PAFs weren’t wound very hot. Plus, it wasn’t an exact science so some of them are wound hotter than others. Jason Lollar is a scientist and I trust his opinion about these sorts of things.

The tone on “Honky Red” is a little different for you. I was saying earlier that you do so many styles. The one I haven’t heard you do much of is heavy metal, but the tone here is a little bit metal. At least on the riff—and that’s coming from an actual metal player. Also, I heard a cover Widespread Panic did recently of “Ace of Spades.”

That was hilarious. Lemmy! I love him. He’s cool. That was JB’s suggestion. He just loves Motörhead and we’ve never covered one of their songs. We all thought it was fun. “Honky Red” came from our bass player, Dave Schools. His dad actually recorded that song. I’m not sure who originally did it. I didn’t know if it was going to be on the album, but we did it live in the room and I was using a PRS with those Lollar Imperials. I’ve probably had that guitar for 17 years or so. It does that fake harmonica shit with the trem, you know. I had that and my Hughes & Kettner Tube Factor overdrive pedal.

You have a unique approach to the whammy bar. Was that something you’ve been experimenting with for a while?

I didn’t grow up with it. I purposely stayed away from it because Jeff Beck is so great with it. He was my reason for not using it. I love Van Halen, but I just never tried to play in that style. As much as I loved him, it seemed like everyone was going that way.

Everybody! And you were in Hollywood at the time, when it was all over the place.

Yeah, that’s true. I doinked around with it on other people’s guitars once or twice, and it felt unnatural to me. Whenever I would take my hand away from the strings to grab the bar, other ugly noises would ring out. When I was about 46—I’m 53 now—I was on tour with Panic and Dave came to me with this giant spindle of DVDs. Many of them were recent Jeff Beck performances. This was before the Ronnie Scotts DVD came out. I watched those and I was stunned. How did Jeff Beck get even better? How did that happen? He drops out of the public eye and he’s even better. His level of expression with that bar, man: I heard him playing bagpipe shit; I heard him playing harmonica; I heard slide guitar—all with that bar. I heard him play “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” and he would hit one harmonic and it would sound like a theremin. I was so struck by it that I had to find out more about it. He was the reason why I never touched it and, in the end, he was the reason I picked it up.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)