Childhood friends Shane McCord, playing his Fender Stratocaster, and Mikey Powers, strumming an Epiphone Sheraton II, are the frontline and songwriting instigators of Sun Club. Photo by Ryan Farber

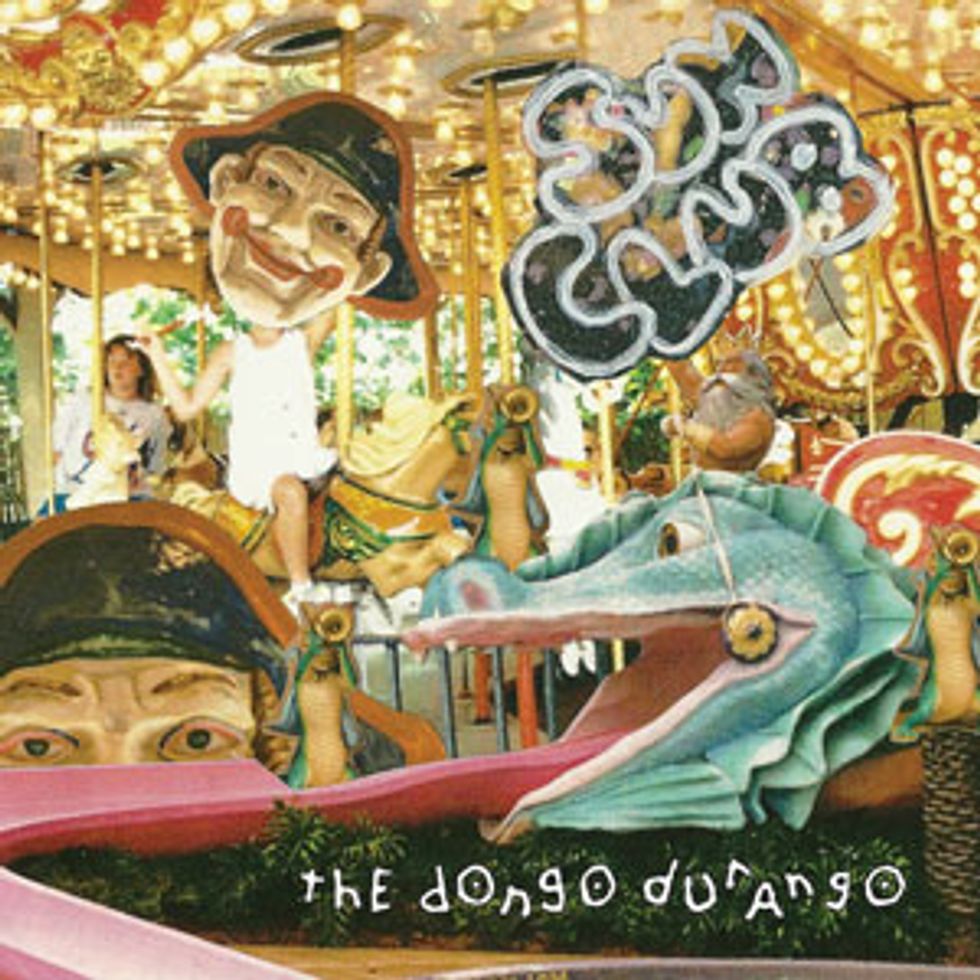

Baltimore’s music scene has emerged as an incubator for some of the most intriguing art-minded pop and indie-rock artists in recent memory, providing a breeding ground for breakouts like Future Islands, Lower Dens, and Beach House—all of whom have enjoyed an uncanny amount of love from fans and critics. If Sun Club’s debut full-length, The Dongo Durango, is any indication of what’s to come, the band is poised to be the latest Charm City musical export to hit the big time.

The Dongo Durango—which was recorded in a warehouse in Baltimore’s Pigtown section—is a spastic, exasperatingly heartfelt statement that fuses elements of ’90s psych-pop, pseudo-African sounds, and unconventionally wielded effects to make a dreamy landscape of disarmingly positive music. Rife with crashing walls of reverb, driven by two drummers, and full of unexpected rhythmic twists and turns, the album is certainly weird enough to hook even the deepest psych fans, but approachable and melodic enough to charm those with less adventurous tastes.

Sun Club is made up of childhood friends, some of who have been making music together since they were middle schoolers. The band made its debut in 2009 at the Sidebar, an all-ages rock club a few blocks from Baltimore’s inner harbor. And they recorded a 7-inch single and a 2013 EP, Dad Claps at the Mom Prom, before joining Alabama Shakes and My Morning Jacket on Dave Matthews’ ATO Records for The Dongo Durango.

Guitarist/songwriters Mikey Powers and Shane McCord work in tandem to create Sun Club’s calling card: walls of guitar that twist and coalesce between monoliths of reverb-drenched chords and twinkling legato lead lines. Premier Guitar spoke with the 6-stringers about the band’s writing process, the novelty and creative benefits of cheap gear, and the intuition that results from a working relationship forged in adolescence.

What influenced the songwriting on The Dongo Durango?

Powers: It had more to do with our environment at the time as a band—what we were going through as people and finding sounds that match what we were feeling—rather than a handful of bands we’d been listening to at any given time. We wrote all of the songs on The Dongo Durango over what wound up being a nearly three-year period, so it really is all over the place. The songs are all very different ideas coming from very different places.

McCord: When we’re writing music, we never think to go after another artist’s sound, but we try to follow the feeling or vibe of guitar parts we come up with. If it happens to feel nostalgic, or it evokes a feeling of some sort, we go toward that. A driving factor in our writing is emulating feelings and ideas—especially youthful, blissful feelings.

Despite the sonic and stylistic variations in the songs, the album sounds very cohesive, so it’s surprising it was created over such a long time. Was there a mission statement?

Powers: We decided right before recording it that we wanted to work everything into a more singular idea, so that was definitely a deliberate thing. The guy that produced it, Steve Wright, operated as sort of a conduit for our ideas, rather than really changing things or impacting the creative process too much like other producers. He was really open to our ideas and making sure things came out in the final product the way they happened naturally when we wrote them, but he also helped us make sure they fit together nicely.

The record was tracked in a makeshift warehouse studio. Did you bring in your own recording equipment? I know the band has self-recorded in the past.

Powers: It was mostly Steven’s gear, but it was a really makeshift setup that we used and it definitely didn’t feel like a proper studio. The album was really tracked as a live band and the setup in the studio was put together to capture that more than anything.

Did you do many overdubs?

Powers: We tracked two weeks of live and then did five separate days for overdubs. Once we tracked the overdubs, we brought the tracks back to the warehouse and pumped them through a big speaker there to make sure they fit well with what we had.

How does the band write songs?

Powers: It’s actually very collaborative. Shane or I usually bring a part to the whole band and we’ll punch out a structure as a team, and the riffs and licks will often change to better suit what the band is playing—so it really is very interactive.

McCord: Usually it starts with me and Mikey writing guitar parts together. Then we layer the rest of the instruments and end with vocals. Mikey and I have worked together since we were 10, so it’s second nature at this point.

Could you explain how a relationship that extends so far back helps with the creative process?

Powers: It’s always been that way for us, so it doesn’t even faze me anymore. That’s the most normal part of being in this band. It’s always been the same group of people and we’ve got a weird intuition because of that.

McCord: We know how to play off one another really well, but our playing styles change every year, so that relationship changes, too. We’ve transitioned together through all of those styles, though, and we grow together, so we always know how to make it work together. Recently Mikey has been playing more of the beefy chord-based stuff and I’ve been playing more delayed-out, high-pitched textural stuff. But there are no defined roles.

Busting out of Baltimore’s fertile indie-rock scene, Sun Club has developed an original approach to psych-rock that uses buoyant melodies and reverb-soaked sounds to create joyful music. Photo by Shervin Lainez

There’s a lot of interplay between the guitars—especially things like the big walls of reverb-drenched chords meshing with the twinkling legato leads that are the band’s signature. How do you work those parts out? Are they generally premeditated or bashed-out in a live setting?

Powers: Both, but it’s all really relative and specific to each instance. It’s never been a super-formulated process for us—though it has become a formula lately, which is a problem we’re actively trying to solve. We always try to avoid formulas and we like to keep things sounding fresh and spontaneous.

I hear a lot of African rhythmic ideas and tones in the guitars. Are either of you steeped in that music at all?

Powers: Honestly, not really! We get that question a lot, and I think people are just picking up on the fact that both guitars are always doing different rhythmic things in our music. It also has a lot to do with the drums in our songs, maybe, more than our guitar playing. The drums really lend themselves to that sound in a way.

Shane McCord’s Gear

Guitars2005 Fender Stratocaster

Fender Telecaster

Amps

’65 Fender Twin Reverb reissue

Effects

Electro-Harmonix Holy Grail Nano Reverb

Boss PS-5 Super Shifter

DigiTech X-series DigiDelay

Danelectro Fab Echo

Boss TU-2 tuner

Strings and Picks

GHS Boomers (.011–.050)

Mikey Powers’ Gear

GuitarsESP LTD EC-256

2009 Epiphone Sheraton II

Gibson Les Paul Studio (used for The Dongo Durango, it belongs to producer Steve Wright)

Amps

Fender Hot Rod DeVille

1x15 cab

Effects

Electro-Harmonix Holy Grail Reverb

TC Electronic Hall of Fame Reverb

MXR Analog Chorus

Line 6 Echo Park

Danelectro Dan Echo

Boss TU-3 tuner

Strings and Picks

GHS Boomers (.011–.050)

Most of the music we listen to and really try to emulate and recreate—if we have to name something—are local bands from in and around

the Baltimore scene … bands we’ve been

watching since we were younger. Those are the bands we look up to far more than what’s going on in the bigger picture.

McCord: I think the African influence people hear is really just because we’re so percussive and rhythmic—especially having two drummers drive so many of our songs. I also think it’s kind of funny, because around 2008 a whole bunch of bands that probably never listened to anything beyond Paul Simon’s Graceland started getting labeled as “Afropop,” and I think a lot of the bands really

didn’t go for that sound on purpose or do much homework, but the press just wanted to put them

in a genre box. I like that sound, but it always

made me laugh when people started labeling that stuff. I don’t know any African music, personally. I want to learn about it, but it’s never been something I’ve done much research on. I’d rather people think we’re coming from a more unique place, or have an African influence, than simply lump us in as a typical indie-rock band.

Beyond the drums, I hear a lot of that apparent influence in the upper-register guitar licks, and even in some of the tonal choices for the guitar.

McCord: The twinkling higher-up stuff is typically me, so that’s cool to hear! I’m not really sure

where that style developed in me, but we had some friends in a band called Hounds when we were younger—they broke up a while ago—that used a lot of short-but-heavy delays on their

guitars and worked with a lot of little lick ideas much more than chords, and had a heavy percussion side like us. They were probably our biggest influence, whether we realized it at the

time or not.

Which Baltimore bands were influential?

Powers: Sherman Whips is an awesome band we’ve played with a lot and really like. There’s a band called Slender Man that really kicks ass and we love them. Everyone in Sun Club likes different locals from the scene, but the scene as a whole has had a real impact on our approach.

As a guitarist, do you have anyone that you take direct influence from?

Powers: Avey Tare from Animal Collective has always been a big deal for me, but I’m not super into the hero worship thing. We—Shane and I—just happened to learn to play guitar as our first instrument and it became our tool by default. We’ve obviously developed our own little tricks that have become a part of our style over the years, especially with effects. It’s rare we aren’t using an effected guitar sound. A lot of our guitar playing, while not washed out, always has something heavy going on with effects.

McCord: I really respect when people get super into their guitar playing and gear, and I know a lot of people who are really deep into their identity as a guitarist, but for me, I don’t consider myself a serious guitar player. I play guitar, but it’s a way to get my music out and play parts in a band. I also write a lot on piano and sample electronic things. I do what I do within this band in a way that works well, but it’s more a vehicle for expression than anything.

YouTube It

Entering on a swell of feedback and ringing notes, Sun Club performs “Tropicoller Lease”—which appears on their debut album, The Dongo Durango—at Chicago’s Audiotree studio live series. At the 0:40 mark, Mikey Powers’ African sounding guitar licks kick in, relenting to the band’s lock-step beat, and then resuming. A joyful, hypnotic performance packed with exuberant dynamics, it perfectly showcases the band’s approach.

What effects made important appearances on the album?

Powers: The Hall of Fame Reverb by TC Electronic was a big part of my sound on the album. That pedal does literally everything you need it to do. I also use an Electro-Harmonix Holy Grail a lot, and my delays are always changing, but I always have one set for a straight-forward long delay and one set for a slapback sound. It’s never consistent and I’m always tweaking and swapping things out.

Are you chasing a specific sound with your swapping?

Powers: No, I’m just into rummaging through used music shops, and if I find something I like, I’ll buy it. It’s weird, but I normally love the sound of cheap used $30 pedals way more than I like any really expensive new pedals. It’s typically not as clean a sound, and they distort in weird ways—and that sounds more to me like a band than a computer-generated type of sound, which is how I hear a lot of new pedals.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.