Unlike the prehistoric mammal it’s named after, Atlanta-based metal quartet Mastodon is

adept at evolving. The band’s 2002 debut, Remission—a sludge-metal concept album—

had guitarists Brent Hinds and Bill Kelliher combining Dream Theater-level technicality

with Sabbath-meets-Motörhead grooves and moods, and even a slight nod to the Allman

Brothers on “Ol’e Nessie.” Mastodon’s sophomore effort, 2004’s Leviathan, was an onslaught of headbanging

goodness with a little Thin Lizzy panache mixed in. It garnered the band Album of the Year

awards from Kerrang!, Terrorizer, and other publications catering to the metal crowd.

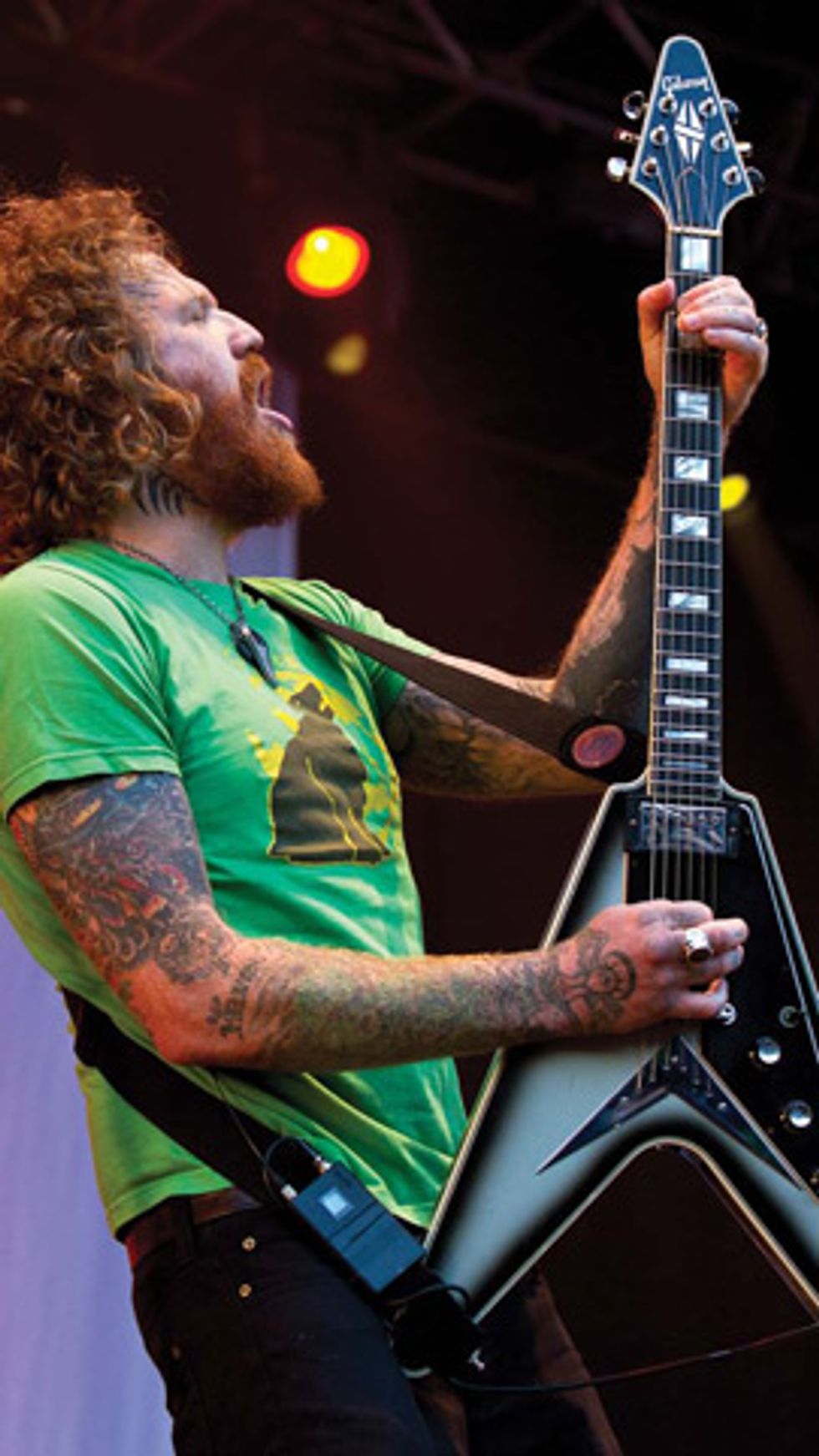

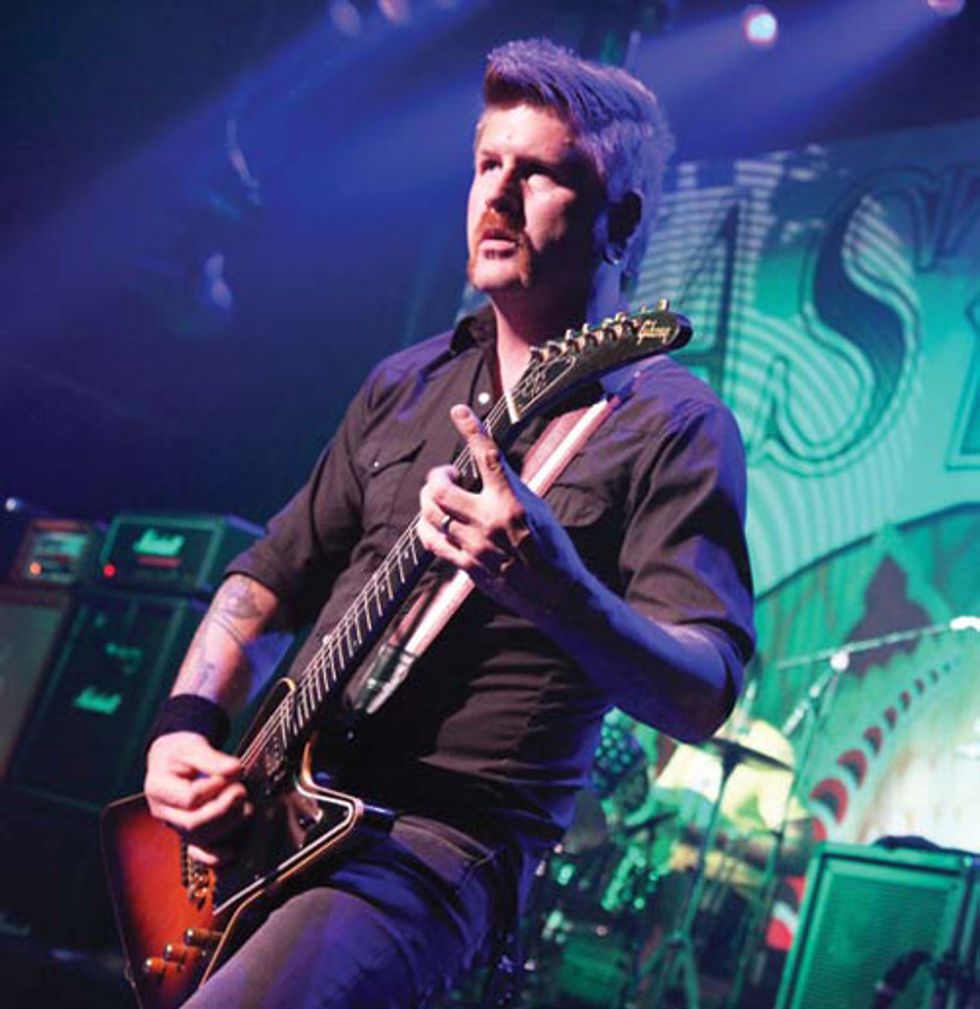

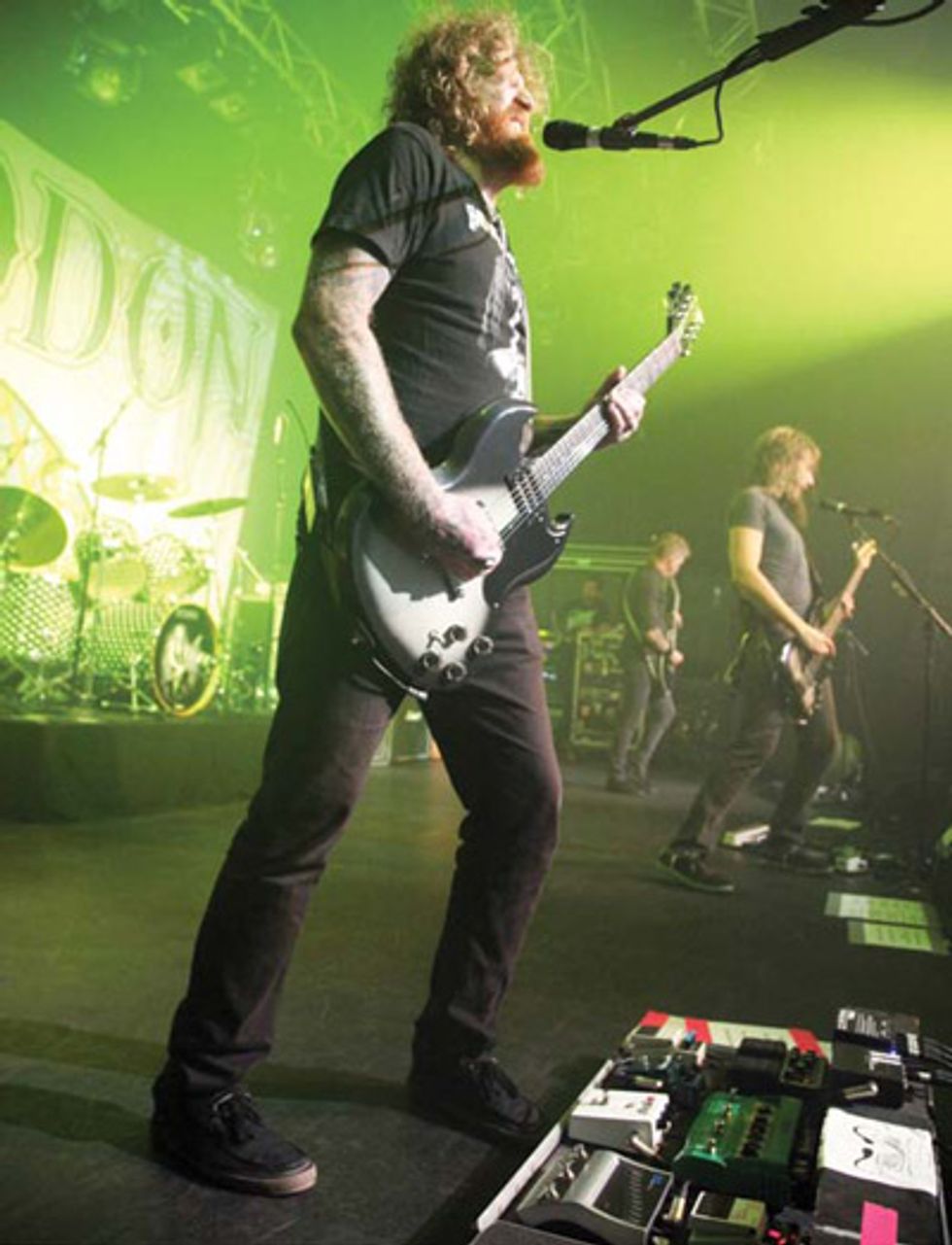

LEFT: Bill Kelliher onstage with one of his Gibson Explorers at a June 2011 gig at the Patronaat in Haarlem, Netherlands. Photo by Cindy Frey Right: Brent Hinds with his silverburst Gibson Flying V at a June 2011 Mastodon appearance at the Norwegian Wood festival in Oslo, Norway. Photo by Per Ole Hagen

Up to that point, the band’s vocal approach had leaned more toward guttural roars, but 2006’s Blood Mountain saw a shift, with Hinds and bassist Troy Sanders—who share vocal duties—exploring a more melodic bent. But the band’s biggest leap forward—both creatively and commercially—came with 2009’s Crack the Skye. By far the tightest, most cohesive album in their catalog up to that point, the seven- song epic showed hints of Pink Floyd and Yes influences, as well as expanded guitar palettes: Hinds and Kelliher dialed in more clean tones, and their First Act Custom Shop 9- and 12-string axes provided a sound that Hinds described as a “ringing, atonal chorus effect unmatched by any chorus pedal.”

However, for this year’s The Hunter, Kelliher and Hinds veered away from the concept approach. “The new album is about nothing,” says Hinds, who also leads the surfabilly band Fiend Without a Face and several other side projects during Mastodon downtime. But the difference on The Hunter isn’t just lyrical. On past albums, Hinds took the lead on riff writing, but this time around Kelliher contributed more song ideas, and both wrote and recorded their own riffs and songs individually. “It’s tighter because we did it this way,” says Kelliher. Both guitarists also experimented with new gear.

Your previous albums have been pretty epic. How did your approach differ for The Hunter?

Kelliher: With Crack the Skye, most of those riffs were written by Brent, but this time we all contributed musical ideas. We decided to take a different approach, because we’re all pretty busy outside the world of Mastodon, and after touring for nearly two years we really wanted to take a break. Before The Hunter, when Brent would a write a song—or vice versa— the other person would learn it and double it, or come up with their own complementary part. But on The Hunter, there are parts and songs where it’s strictly Brann [Dailor, drums] and me or Brent and Brann—that’s something we’ve never really done before.

Hinds: I really didn’t approach The Hunter any different than our previous albums. We just decided—like we always do—to write and record a cool album that’s badass, and to do the best we can. I play guitar so much in Mastodon and my other bands that I don’t really block out time to write—if something comes to me while I’m jamming and it sticks with me, I’ll generally try recording it. But if I forget the riff or idea, then it probably wasn’t meant to be.

Bill, are you happy with how the different writing approach worked out this time?

Kelliher: It was real spontaneous— some of the stuff was even written while in the studio rehearsing and recording other songs. But honestly, I was really nervous about going at this album with the attitude of “Let’s just go record—even though we don’t know each other’s parts.” But our producer, Mike Elizondo, reassured us that a lot of bands do it that way—he mentioned that James [Hetfield, vocalist/rhythm guitar] in Metallica records all his parts, and then Kirk [Hammett, lead guitar] comes in and records the solos. Don’t get me wrong, though—the stuff we’ve done in the past, with those contrasting guitar tones and mannerisms, do give a song a bigger feel. Brent and I, James and Kirk of Metallica, or any two guitarists are never going to play the same song or the same riff the same. So I feel The Hunter is a tighter album because we did it this way.

The whole album seems to groove a little more than past albums, especially on songs like “Black Tongue,” “Curl of the Burl,” and “Blasteroid.” What do you attribute that to?

Kelliher: I think it was the atmosphere and mentality of not feeling pressure to perfect every nook and cranny of every song. We just went at it with a fun, low-key attitude that allowed us to really go places we’ve haven’t explored yet with Mastodon. With “Curl of the Burl,” that was a chorus and drum riff that Brann had for a long time, and Brent came in and added the intro riff. Whether a song is a skull-crusher or a ballad, you need to have a catchy groove— that’s something we strive for on every song. If you can’t write a great song, at least write a great groove [laughs].

Kelliher plays his 1974 Les Paul Custom and Hinds plays his Electrical Guitar Company signature model while tracking The Hunter at Doppler Studios in Atlanta, Georgia. Photo by Andrew Stuart

What was it like working with Mike Elizondo?

Hinds: Amazing. Mike is a great man—I’d vote for Mr. Elizondo for president. I really liked working with Matt Bayles on our first three records, even though it was a battle at times, because we weren’t really known or trusted as musicians yet, so we’d have creative conflicts like you would in any recording environment. Brendan [O’Brien] was the guy for Crack the Skye, but I’m glad we went with Mike, because he let us do our thing while maintaining some control and having lucid and constructive input for our song structures and guitar parts.

Kelliher: Brendan was the right choice for Crack the Skye, because we wanted that ’80s classic-rock sound, and Brendan has worked with so many acts of that genre— like AC/DC and Springsteen—so it was just the perfect fit. That album was so dialed-in and meticulous that it was helpful to have a guy pushing for perfection. But we did so many sessions and takes that it was grueling. Mike was full of energy and so excited to be with us that it just immediately clicked. Usually, when I record my parts in the studio, no one is very vocal or directing me if something sounds bad—or suggesting I try it in a different key or with a different guitar. But Mike was really vocal on what was working and wasn’t for my guitar parts.

What sorts of things would he say?

Kelliher: Sometimes I’d be going overboard with my solos or adding too many tracks. I kept layering “guitarmonies” [harmonies] and ambient noises, and it would be too much at points and he’d let me know that what I originally recorded was good enough. It was a good, creative back and forth.

Which song would you say he was particularly helpful on?

Kelliher: “Black Tongue.” The verse riff was an old riff I’d been hammering on for years, and the beginning riff for the chorus was something Brann came up with when we were messing around in rehearsals. The part that ties it altogether is the middle section with its groove—I came up with that while jamming alone one night. And then we recorded all the parts and glued them together with Mike’s help. I really like the guitarmonies I came up with by accident one night in the studio. I actually did half of the solo—the first 20 seconds—on my laptop in a hotel room in France while we were on tour. That shows you how this record was done in comparison to Crack the Skye, and how far technology has progressed. I completed that solo’s harmony part at 4 p.m., emailed it to Mike, and then he mixed it and sent us the finished song the next day. It’s amazing that you can write and record ideas thousands of miles away for your album [laughs].

What did you use to record in the hotel room?

Kelliher: I had a Yamaha SBG2000 and my Marshall Micro Stack and some Shure condenser mics I was going to use, but I decided to run it through AmpliTube’s Marshall amp models, because Warner Bros. was asking for the song to be done so they could release it as a single the next morning in the USA. I was like, “It’s not done yet!” [Laughs.] When I got done, I was so proud of myself and felt really good about it, because I had gotten it down and everyone liked it. I kind of live for moments like that. I’m a multitasker by nature. My wife says I should focus on one thing at a time—because I’m always doing several things at once—but in this instance it worked out. The deadline forced me to work some fast magic, but I don’t advise anyone to do that on a regular basis!

What did you use for the other half of the solo?

Kelliher: The second part of the solo was done in the studio before that European tour, and I really like it because it has that “Orion” [from Metallica’s Master of Puppets] feel and groove. I used this new Gibson Explorer with EMG X Series 81 and 85 humbuckers. It’s a metal-shredding beast that doesn’t sound phony—it’s quickly become my go-to super-heavy guitar. I plug straight into the amp for the majority of my recordings, so when I need something gargantuan, I have that in my back pocket. I used to hate active pickups and thought they sounded brittle and stale, but I totally dig their tone with my Explorer—it’s a clear, concise, unique distortion. I use that guitar a lot on “All the Heavy Lifting” and some of the harmonies on “Curl of the Burl.”

With its Alan Parsons Project-/Pink Floyd-style synths and chanting choirs, “The Creature Lives” is very theatrical. What was the impetus for that song?

Kelliher: [Laughs.] That was all Brann’s idea. He wrote it years ago and he pretty much directed and composed how everything fell into place. He thinks it’s going to be one of those lift-your-lighter-in- the-air-and-sway songs. I’m sure Mastodon fans will think, ‘What the hell is this?’ But I’ve heard some people compare it old Pink Floyd, with the prog-y Hammond organs. Crack the Skye was a serious record—it was a healing process for a lot of people. And that’s not to say The Hunter isn’t going to cure some ills, too, but we wanted to do a party record that was fun to make—and hopefully fun for fans to crank up and jam with some friends.

Kelliher barres his 1980 Gibson Explorer at a June 2011 Netherlands gig. Photo by Cindy Frey

What’s your favorite part of the new album?

Kelliher: I’d have to say the middle of “All the Heavy Lifting,” where there’s all this craziness between my guitar parts and Brann’s drumming. It was a spontaneous riff that I wrote while we were putting the song together, and I kind of just made it by the seat of my pants with all this creative energy swirling and pressure mounting.

Hinds: The guitar-and-drum solo part in “The Hunter”—where Brann and me play off each other—it screams “Check this out!” When you hear me and Brann bounce off each other in those moments where he takes the lead with some fills and I’m sustaining, and then I take over again—it’s a really cool thing to be in a band where you have that romantic cadence between the different instruments. I’m not sure if Deep Purple was one of the first bands to have a drum solo and a guitar solo going at the same time, but I like how it turned out a lot.

“Bedazzled Fingernails” has some pretty mind-boggling stuff going on with the timing and the riffs. How did that song develop?

Hinds: You’re, like, the third person that’s interviewed me that has asked about that song— that’s a great sign. That has been a riff I’ve been playing around with for a long time, but it never really worked in anything else until The Hunter sessions.

Those syncopated riffs sound pretty difficult to play.

Hinds: That’s the whole point—it sounds difficult, but that doesn’t mean it is difficult. Guitar playing is like being a magician—you try to do more with less and work smarter, not harder. I’ve played with hybrid-style picking—using a pick along with my middle, ring, and pinky fingers—forever, because I learned on the banjo first. But on this song I don’t really use a pick that much, I’m just using my open fingers with hammer-ons and pull-offs to get that confusing, high-speed riff illusion.

The main riff in “The Octopus Has No Friends” sounds pretty brutal, too.

Hinds: That’s just how I play guitar. That type of hybrid picking will always be a big part of my playing—whether it’s in Mastodon or my side bands. For “Octopus,” I just wanted to make things sound as crazy—like raindrops—and chorus-y as possible, so I really worked it up to speed on my 9-string First Act, because it creates those natural chorus sounds that even the best pedal can’t make.

Did you use your 9- and 12-string First Act guitars on other songs?

Hinds: They’re probably featured on nine of the 14 songs. I love playing big, open chords on them, and then also layering jangly parts when picking the strings really fast. The octave strings create this ringing, atonal chorus effect unmatched by any chorus pedal. A 6-string and a pedal sounds stale in comparison. Kelliher: I didn’t really use those at all on this album. They offered those ringing dynamics and overtones we were looking for on Crack the Skye, but that wasn’t something I strived for on The Hunter.

What was your go-to guitar for these sessions?

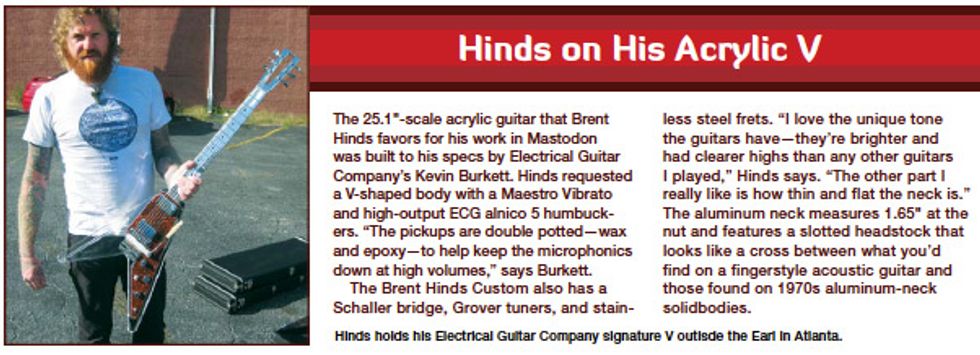

Hinds: My Mastodon guitar would have to be the Electrical Guitar Company acrylic V that Kevin Burkett built me a few years ago. I’ve always loved Gibson Flying Vs, and my friends King Buzzo [the Melvins] and Laura Pleasants [Kylesa] had theses killer aluminum-body-and-neck guitars from Electrical Guitar Company. So I talked to Kevin and had him make one of his V models for me. It’s a little heavy still—that’s something we’ll continue to work on—but it sounds great and is unique, as far as looks and tone—especially its sustain.

Left to right: Hinds, Kelliher, and bassist/vocalist Troy Sanders onstage in the Netherlands. Photo by Cindy Frey

Sustain is a big deal to you, isn’t it?

Hinds: Sustain is one of the most important things to me when it comes to tone and my setup. I like it so much, if I had a kid, I’d name it Sustain [laughs]. But honestly, I love sustain because it’s ghostly. It has weird textures, majestic energy, and spooky overtones that add so much depth and soul to your playing—it’s an organic interaction between you, the guitar, and the amp. I live for those overdriven vibrations and emotions.

Bill, other than that Yamaha you mentioned, what guitars did you use for The Hunter?

Kelliher: My main guitar is a ’74 Gibson Les Paul Custom 20th Anniversary tobacco burst that I recently had refretted and set up with all new hardware and volume and tone pots by the Gibson USA Custom Shop. They put in their killer ’57 Classic humbuckers, too. I also got turned on to a Fender Jim Root Telecaster that Jim gave me. It has EMG 81 and 60 pickups, but it still has the Telecaster twang to it—especially when you play close to the bridge. I was surprised. I used that on the intro to “All the Heavy Lifting”— where it has all those high notes—and then again on “Black Tongue,” where Brann’s double-bass part goes, I added some high notes into the mix with it, too.

What about amps?

Kelliher: I used my old, 2-channel Marshall JCM800s, because I always find myself going back to those amps for my tone. I really like the punch they offer and how I can cut through and be heard between Brann’s crazy drumming, Brent’s riffs, and Troy’s bass lines. I used my 100-watt Marshall Kerry King JCM800 for layering and a few other parts, but the main parts were recorded with the old JCM800s. All my amps went through this beat up Marshall 1960B 4x12 loaded with 20-watt Celestions. I love trying new gear all the time, but I always seem to come back to the Marshalls.

Hinds: I used a lot of amps for The Hunter—a Diezel VH4, an Orange Rockerverb 50, a Marshall 100-watt JMP Mark II Lead Series head, and an ’80s JCM800—but the one I used the most was a ’70 Fender silverface Princeton Reverb. No matter what guitar I used with that Princeton, it sounded and performed the best—especially for my single-note runs and clean, textural parts. For the heavier, chunky riffs and distorted solos, I used the big monster heads. I’m old-school like that.

Tell us about the cool, slow warble effect you get with your wah on “Dry Bone Valley.”

Hinds: To be considered a bona fide guitarist, you need to record one wah song. I’m starting to get pretty fond of it—I might start wearing bell-bottoms [laughs]. That slow sweep combined with some serious hammer-ons at the beginning are my favorite—it’s like a helicopter swooping down to capture swimmers in Niagara Falls. Jerry Cantrell got me one of his signature Jim Dunlop Crybaby wahs, and I figured “Dry Bone Valley” has the perfect swaggering, galloping vibe to the chorus and verses that leads right up to the wah solo perfectly.

Did either of you use any other effects on the album?

Kelliher: Probably the only effect I used was my original Ibanez Tube King, for when I really want to take it over the top and soar.

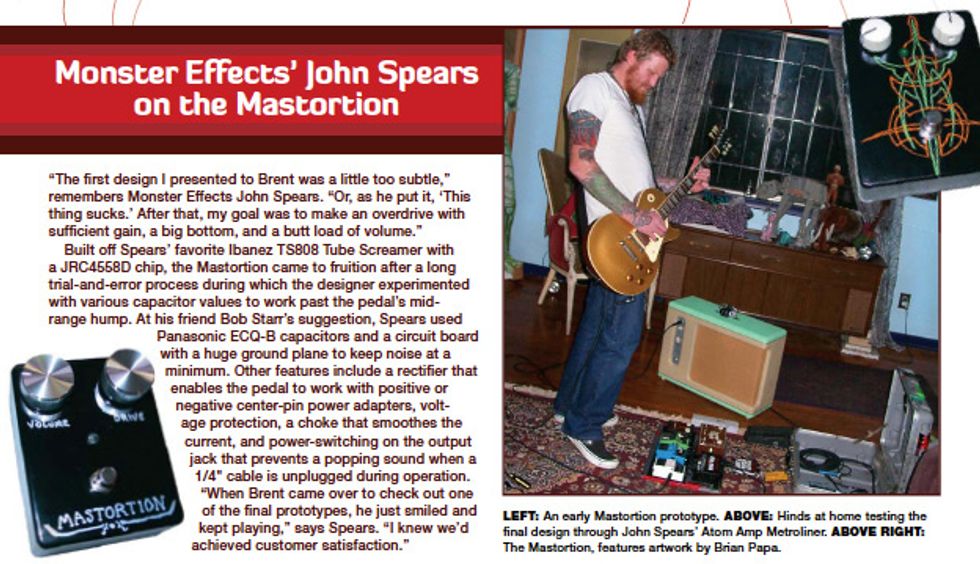

Hinds: I have an old Ibanez TS9 Tube Screamer, a Visual Sound Route 66 overdrive, a Boss RE-20 Space Echo, a Boss DD-6 Digital Delay, a Custom Audio Electronics Boost/Overdrive, a Morpheus DropTune, and a personal favorite is the Monster Effects Mastortion, which my friend John Spears built for me. It’s basically a TS808 Tube Screamer clone with more volume and low-end power.

Mastodon’s guitar sound has evolved over the years from a fast, sludgy barrage to a more melodic and subdued aggression. What do you attribute that to?

Hinds: We used keyboards all over Crack the Skye, and again with The Hunter. Keyboards and organs add another dimension that can’t be achieved with anything else. They give us this old-school, classic-rock vibe that we really want to be a part of the band. I’m sure some metal fans laugh at the organ and its spot in Mastodon, but it’s a badass instrument.

I love playing fast and heavy like we did on Call of the Mastodon and Remission, and we’ll always have that metal feel—because we all love it— but adding the melodies and harmonies, and diversifying our sound all the way up to Crack the Skye has made us a better band. The band we became during those sessions was where I saw us going years ago, but we had to experiment and find it ourselves instead of forcing the issue. And with The Hunter, it was about incorporating all the elements from our previous records and our collective and individual influences, and bringing it together for a fun, good-time, party record. The Hunter represents Mastodon’s full body of work.

Hinds’ guitars (left to right): First Act 12-/6-string doubleneck, First Act Lola 12-string, Gibson SG, Gibson Flying V, and Electrical Guitar Company signature V. Photo by Chris Kies

Brent Hinds’ Gearbox

Guitars

Electrical Guitar Company Brent Hinds Custom, First Act Custom Shop Lola 9-string, First Act Custom Shop Lola 12-string, Gibson SG, Gibson Flying V, Gibson LP-295 Goldtop Les Paul

Amps

Orange Rockerverb 50, Diezel VH4, ’80s Marshall JCM800, ’76 Marshall 100-watt JMP Mark II Lead Series, ’70 Fender Princeton Reverb, Marshall 4x12 with 75-watt Celestions, Orange 4x12, Diezel 4x12

Effects

Monster Effects Mastortion, Ibanez TS9 Tube Screamer, Visual Sound Route 66, Boss RE-20 Space Echo, Boss DD-6 Digital Delay, Custom Audio Electronics Boost/Overdrive, Boss GE-7 Equalizer, Morpheus DropTune, Jim Dunlop JC95 Jerry Cantrell Signature Wah

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXL110s, D’Addario EXL116s (for D, dropped-D, and dropped-C tunings), Dunlop Ultex 1.0 mm picks

Kelliher’s guitars (left to right): Two Les Paul Customs, an EMG-equipped Gibson Explorer, two yamaha SBG2000s, a First Act Lola 9-string, another Les Paul Custom, and another Explorer. Photo by Chris Kies

Bill Kelliher’s Gearbox

Guitars

1974 Gibson Les Paul Custom 20th Anniversary, Fender Jim Root Signature Telecaster, two Yamaha SBG2000s, Gibson Les Paul Custom, ’82 Gibson Les Paul Custom, 1980 Gibson Explorer, Gibson Explorer with EMGs

Amps

Marshall 2203KK Kerry King Signature JCM800, two ’80s 2-channel

Marshall JCM800s, IK Multimedia AmpliTube recording software,

Marshall 1960B 4x12 cabinet with 20-watt Celestions

Marshall 2203KK Kerry King Signature JCM800, two ’80s 2-channel

Marshall JCM800s, IK Multimedia AmpliTube recording software,

Marshall 1960B 4x12 cabinet with 20-watt CelestionsEffects

Ibanez Tube King Overdrive

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXL140s, Jim Dunlop Custom Bill Kelliher Tortex Sharp .88mm picks

YouTube It...

Kelliher and Hinds tear it up on one of Mastodon’s heaviest Remission-era songs at the 2005 With Full Force Festival in Germany.

This 2006 performance of Leviathan’s 13-minute opus in Nottingham, England, opens with broodingly overdriven guitars and slowly builds to a tidal wave of epic metal.

This video from a 2009 Chicago gig shows Kelliher playing his custom First Act 9-string and Hinds playing his custom First Act 12-string on “Ghost of Karelia” from Crack the Skye.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)