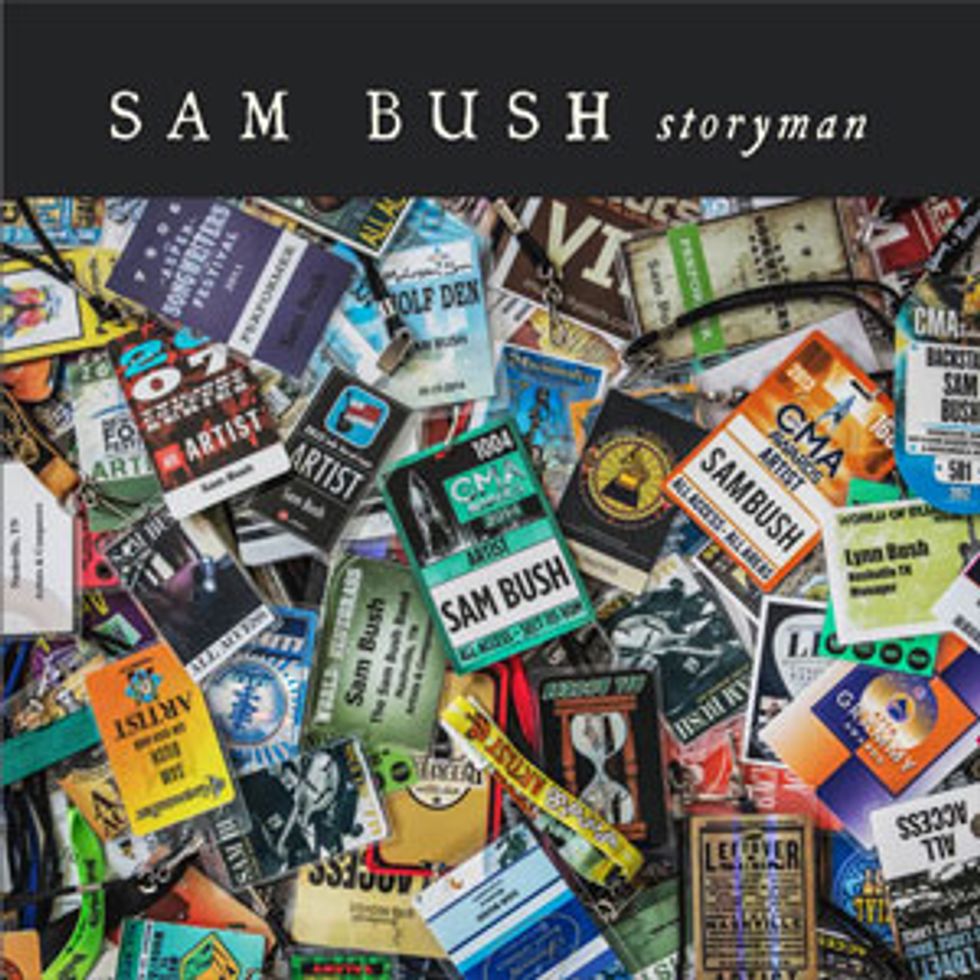

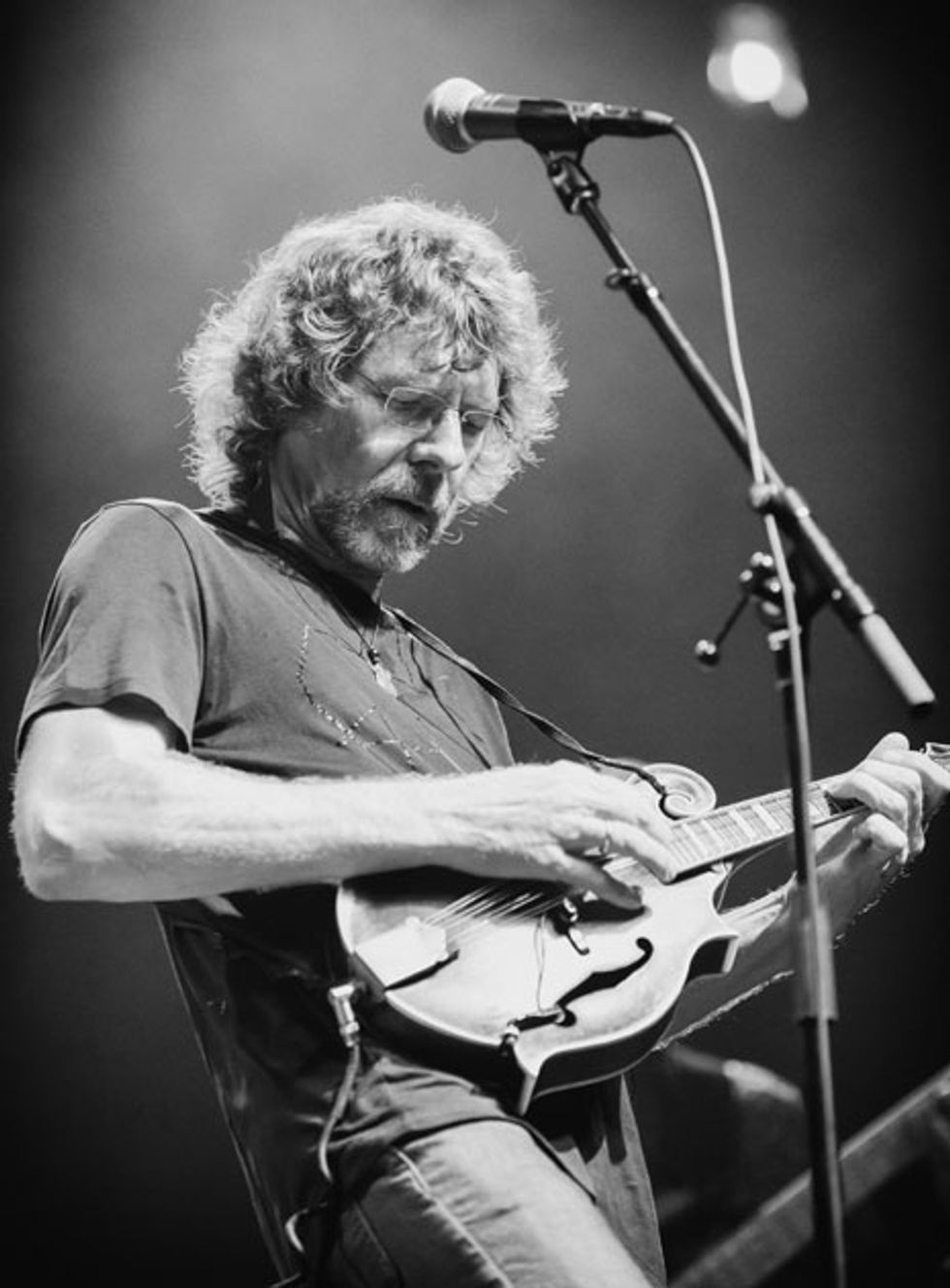

In the opening verse of “Play by Your Own Rules,” the first track on mandolinist Sam Bush’s latest record, Storyman, he sings, “Take ahold of the wheel and turn it for yourself.” Bush may be offering this sage advice to his listeners, or may simply be reminding himself to keep on doing what he’s been doing for the past 40 years or so. Though the native Kentuckian is respectful of musical traditions—particularly those of bluegrass and old-school country—he’s built his career on crossing musical borderlines and blazing new trails.

Bush’s best-known alliance was New Grass Revival, the band he cofounded in the early 1970s. New Grass Revival used classic bluegrass instrumentation—with banjo, Dobro, and mandolin—to propel fresh grooves and tell stories that resonated with their own generation. Though the band never sought to snub the music’s past, they always seemed determined to look forward more than backward.

In 1989, Bush decided to disband New Grass Revival and launch his solo career with the Sam Bush Band. Bush’s eponymous ensemble has been going strong ever since, with a few personnel refinements over the years. The band now features guitarist Stephen Mougin, Scott Vestal on banjo, Todd Parks on bass, and drummer Chris Brown—with Bush himself on vocals, mandolin, and other stringed instruments. The quintet plays to their individual and collective strengths on Storyman.

From his home in Nashville, Bush spoke with PG about the comfort zone that comes with keeping a band together for many years, the guitarists who influenced his mandolin style, and what it means to be a storyteller.

we can play guitar.”

“I Just Wanna Feel Something” sounds so dynamic and spontaneous. Do you and the band record together in the studio—like a live performance?

We set up with separation, but, yes, the five of us cut live. That’s the way to do it. There are three soloists on that one: Stephen, Scott, and me. We were really trying to maintain some space within the soloing to keep the feel of that song. It’s about the joy of jamming.

How long have you had the band together in this configuration?

Todd Parks, on bass, is the most recent member, since 2010. Stephen and Scott joined around 2006. It’s a very comfortable feeling when we walk onstage. I’ve been asked, “Do you get nervous before a show?” I’m, like, “No! I just wanna get on.” When I get to play with those four guys, I’m never nervous.

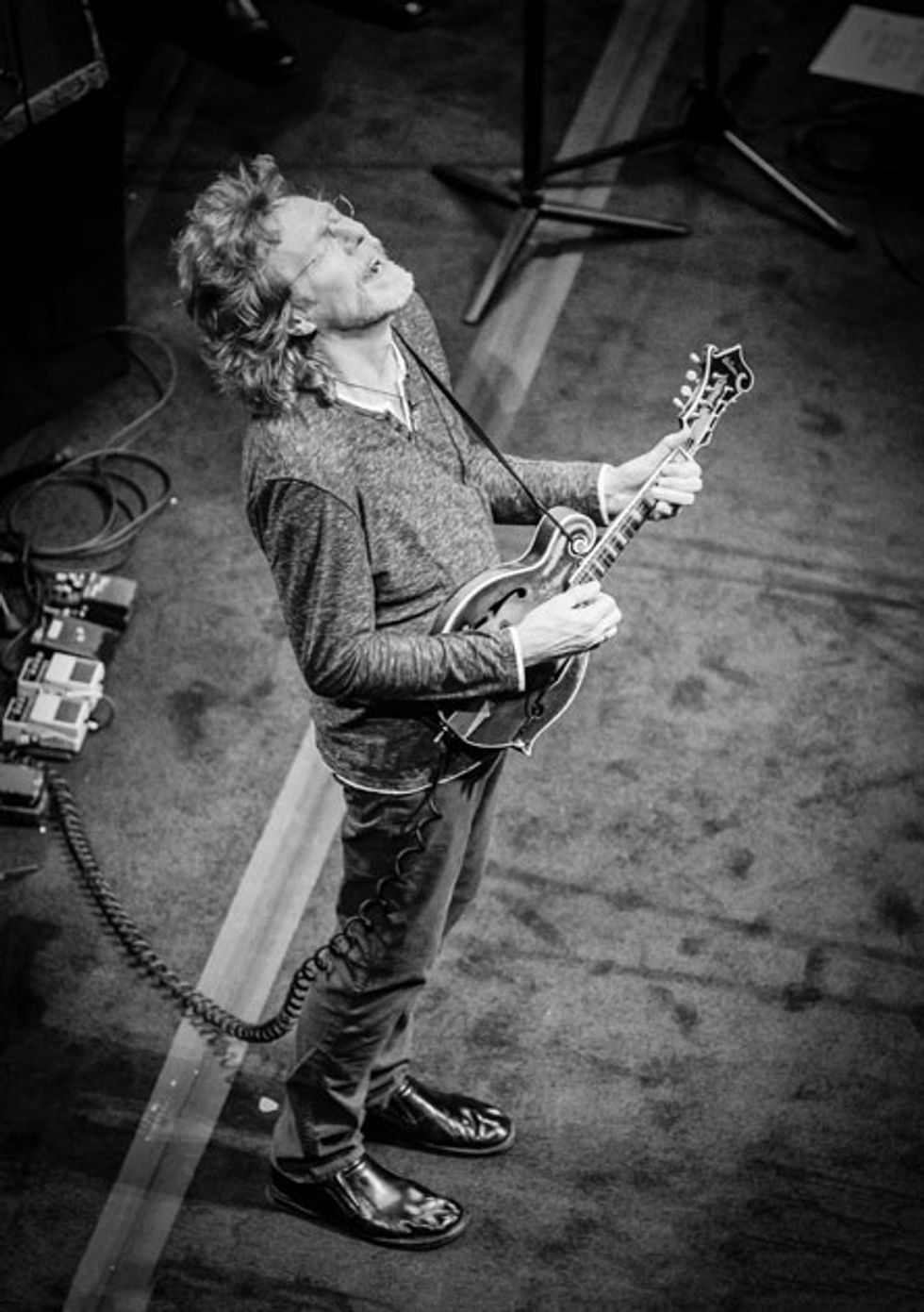

Speaking of playing live, how do you reproduce your rich mandolin tone onstage—presumably in some less-than-ideal acoustic environments?

It starts with the mandolin and the player. In this case, the mandolin is one I’ve owned since 1973—a 1937 Gibson F5, named Hoss. With Hoss, I use a Barcus-Berry pickup from the ’70s that was originally made to be put in the bridge of guitars. I don’t glue them in. I just wedge them between the adjustable pieces of the mandolin bridge. I also have a Countryman Isomax 2 microphone on my instrument. Both of these go to a stereo jack, then out to a preamp called the Chard Stuff Acoustic Helper preamp, which was made by Richard Battaglia, the longtime soundman for New Grass Revival. He developed these preamps to accommodate a microphone and your pickup, so that’s part of the sound.

In your song “Handmics Killed Country Music,” you talk about listening to the Grand Ole Opry show when you were growing up. Is that true?

I grew up in Bowling Green, Kentucky. When the reception was good, we could listen to the Grand Ole Opry and watch Nashville television stations. I got to see and hear all these great country-music shows, assuming everybody else did that on Saturday afternoons, too. Later on, when I started traveling for a living, I learned that most of those shows were syndicated for Nashville and not everybody in America got to see them.

FACTOID: In addition to his maestro mandolin playing, Sam Bush also plays guitar—notably on the track he wrote with Emmylou Harris, “Handmics Killed Country Music.”

Growing up in the ’60s, I also got to watch The Ed Sullivan Show. I saw all the Beatles performances, and the Rolling Stones when they did “Let’s Spend the Night Together” and had to change the words. It was a great time to grow up.

I thought “handmics killed country music” would be a fun line to sing. I cowrote that song with Emmylou Harris. As we were writing, we realized that we used to identify people back then with what kind of guitars they played. Ernest Tubb and Loretta Lynn had these beautiful Epiphones. Don Gibson played a Gibson Super 400. When we first saw Porter Wagoner, he played Martin D-28, then later became known for his Gibson J-200. We talk about that in the song.

What turned the tide? It must have been television, in the ’60s, making stars out of good ol’ country boys. When they took away their guitars, there was nothing left to hold onto but microphones. The song is meant to be lighthearted—we’re not preaching. And, of course, nothing is killing country music.

I like the acoustic guitar fills on that one. Is that Stephen Mougin?

That’s actually me playing the guitar fills on there, while I cut my vocal. I have the mandolin player’s disease—we all think we can play guitar.

You really do play guitar! While doing research for this interview, I stumbled upon a clip of you playing “Mustang Sally” on a Gibson Firebird.

Rock ’n’ roll has always been a love for me. Blues too—especially on guitar. Back in Bowling Green, my friend Kenny and I used to sit my bedroom and work on B.B. King licks and Freddie King licks.

Sam Bush has owned “Hoss,” a 1937 Gibson F5, since 1973. He uses a ’70s Barcus-Berry pickup that he wedges between the adjustable pieces of the mandolin bridge.

There seems to be a hint of Duane Allman in your slide-mandolin playing on “Lefty’s Song.”

Like many other young musicians, once I heard Duane Allman I had to try to play like him. I read somewhere that Duane used a Coricidin bottle as a slide, so I went right into my medicine cabinet and got to it.

Which instrument are you playing on that song? It doesn’t sound like Hoss.

That’s my 1938 National 4-string resonator mandolin.

What’s your slide tuning?

From the first string to the fourth, it’s D–A–D–A. [Editor’s note: Bush is describing his tuning high to low.] There’s no defining major or minor third in that tuning, so you can’t really play chords, though I do play some rhythm on it. That tuning is a 4-string version of Bill Monroe’s open-D 8-string cross-tuning for “Get Up John.” Bill Monroe never played blues slide mandolin, but he sure influenced me.

Besides Allman-like slide technique, are there other guitar concepts that you’ve integrated into your mandolin style?

Not at every show, but most shows, our band will have an electric portion within our set. For that, I usually play my 1956 Fender electric mandolin. Basically, it’s a miniature 4-string solidbody electric guitar. Having just four strings, I can bend notes. I can’t do that on an 8-string mandolin. So, that’s where I take my electric-guitar knowledge and apply it.

When I talk to guitarists who are trying to learn the mandolin, I understand what they mean when they say the strings are backwards from what they’re used to. I’m fortunate, in that I started mandolin at age 11 and started guitar at age 13. I learned the two instruments together. For me, they’re totally different things. I don’t think of the mandolin when I’m playing guitar.

Who are some of your favorite guitarists?

Eric Clapton, John McLaughlin, and Jeff Beck—they’re the three I love the most on electric guitar, for different reasons.

Why McLaughlin?

I initially became aware of him because I was a follower of the fiddle player in the Mahavishnu Orchestra, Jerry Goodman. I loved the whole Mahavishnu trip. I think I’m just now starting to understand their first album. I remember buying that record, turning out the lights, and listening to it. It scared the shit out of me!

Gear

MandolinsGibson 1937 F5 mandolin (nicknamed “Hoss”)

Gibson Sam Bush model

National 1938 resonator mandolin (4-string)

Fender 1956 electric mandolin (4-string)

Mandolin pickup, mic, and amplification

Barcus-Berry Hot Dot pickup

Countryman Isomax 2 microphone

Divine Noise cable (stereo)

Chard Stuff Acoustic Helper preamp

Polytone Mini-Brute II amplifier (acoustic mandolin)

Fender Hot Rod Deluxe amplifier (electric mandolin)

Greer Ghetto Stomp overdrive pedal (electric mandolin)

Strings and Picks

Gibson Sam Bush signature monel-wound strings (.011–.041)

Fender celluloid picks (.96 mm)

There’s also this song called “Someone” that James Taylor recorded on his One Man Dog album. John McLaughlin wrote it and plays acoustic guitar on it. It’s so beautiful. McLaughlin does that thing—it’s literally float like a butterfly, sting like a bee. There’s definitely some McLaughlin-isms that I’ve brought to the mandolin, certain ways of phrasing.

And Beck?

I saw him a few years ago at the Ryman Auditorium here in Nashville. I walked away thinking, “That was the greatest guitar show that I’ve ever seen—by anyone.” It was playful and joyful. People might think of Jeff just for his hot licks, but his melodic sense is awesome. And some of the things I’d always assumed he was playing with a slide—no, he’s not. It’s just in the way he plays.

When you go back and forth between the mandolin and guitar, do use the same type of pick?

I grew up playing with the standard-shaped guitar pick. I don’t use the pointed edge when I’m playing mandolin; I use the two rounder edges. I think it’s a little bit harder on your thumb and first finger to hold the pick that way, but that’s part of the tone. For flatpicking on acoustic guitar, sometimes I’ll switch to the point to help the notes cut through.

Listening to you talk about Storyman, and about instruments and players, it’s clear that you really are a gifted storyteller. When you’re improvising a solo, do you feel like you’re telling a story instrumentally—without words?

Years ago, I used to play with Leon Russell. One night, Leon brought on a harmonica player named Juke Logan. Man, he was like Little Walter reincarnated! One night, we got into this jam onstage. I was playing my Fender electric mandolin, trading lines back and forth with Juke on the harp. After the song ended, we just went and went. I saw Juke was getting all red in the face. After the set, he came up to me and said, “Hey! I gotta breathe! And, by the way, I think if you learned to breathe in your phrases, then your playing would improve about 75 percent.” That really got me thinking about space and phrasing and stuff.

When I’m improvising a solo, if I’m succeeding, I’m making a melody on the spot. There’s a start and a finish, and it all goes together. You try for that every time. It can’t always happen, but that’s the goal. When you’ve succeeded, you’ve made a phrase that’s melodic. There’s Jeff Beck for you, right there.

YouTube It

Though Sam Bush is best known for the “new grass” sound he pioneered, a blues-rock streak runs right through the middle of his heart—as is evident in this solo performance. Here, Bush tips his hat to Lowell George and Eric Clapton as he segues from Little Feat’s “Sailin’ Shoes” into Cream’s fiery “Crossroads.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)