Only a handful of people can say they’ve hefted and played Duane Allman’s ’57 Les Paul goldtop, but none of them had thought to track a whole album with it, let alone use the Allman Brothers’ famed Big House in Macon, Georgia, as the recording studio. None, that is, until Nashville-based axeslinger JD Simo came along. Let Love Show the Way, his barnstorming power trio’s latest slab of electric hard rock, has a great backstory and is a reverent nod to the past, with a tube-warmed glimpse of a freewheeling future. But the incredible live presence of this band is where we’ll start.

Sparks, splinters, and copious locks of hair fly around the small basement stage at Bowery Electric, just a few doors down from where bands like Television, Talking Heads, Blondie, and the Ramones once shook the walls at the legendary New York punk mecca (and now sadly defunct) CBGB. Fully cranked through his exquisitely vintage 100-watt Marshall half-stack, 29-year-old JD Simo uncorks a smoldering solo over the hypnotic break of “I’d Rather Die in Vain,” the 10-minute epic staple of his band’s explosive live set and one of many dizzying highs on the new album. In the space of two minutes, Simo channels everyone from Hendrix to McLaughlin to Peter Green to Derek Trucks, throwing his whole body into the performance and exhorting bassist Elad Shapiro and drummer Adam Abrashoff to join him in the ritual—which they duly oblige.

There’s definitely something of a shamanistic vibe in what Simo delivers live, and with his eye-catching Les Paul sunburst in hand, he looks every bit the image of the sky-bound ’60s guitar hero. He can make any playing style seem accessible, from fluid bottleneck slide in the vein of his hero Duane Allman to the chicken-picked runs of Tele kings like Johnny Hiland or Danny Gatton. But he’s quick to point out that even though the band SIMO bears his name, the mission isn’t just about him.

“I accept the leadership role in the group, but that’s what it is—a group,” he insists. “That’s very important to me. It means you’ve gotta find people you jibe with, but who are also in a situation where they can invest with you. Those two things don’t necessarily meet up, but luckily it happened, so we have a very healthy thing going.”

If he sounds modest, it’s probably because Simo has paid his dues, and he feels blessed to have caught some breaks along the way. A native of Chicago’s north side, he got hooked on the blues as a kid, taking up the harmonica after he saw The Blues Brothers movie and then switching to guitar once he started digging into the work of Steve Cropper. As it turned out, the youngster was a prodigy. By the time he was 13 he was jamming on stage with Dick Dale, and throughout his teens, on the festival circuit, he opened for the likes of Santana, Slash, Buddy Guy, and B.B. King.

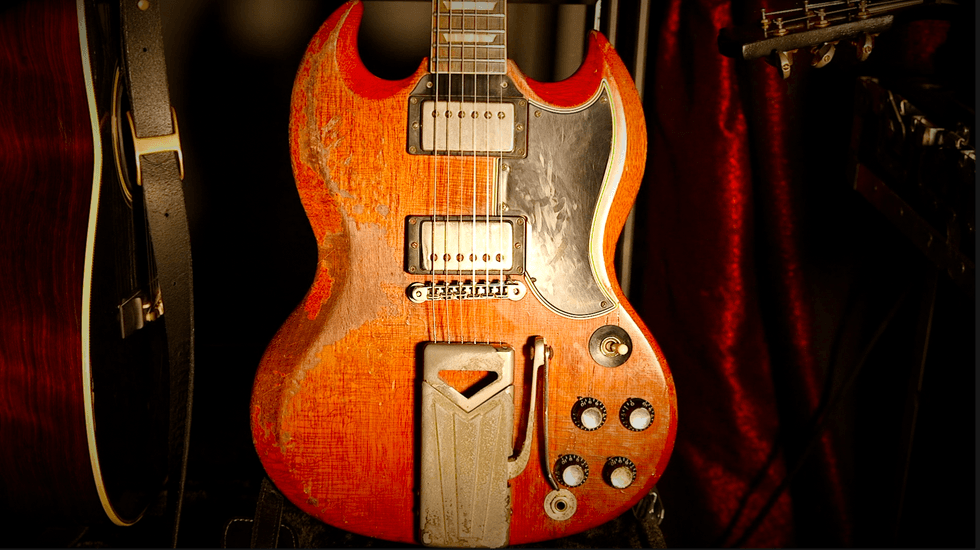

JD's 1960 Les Paul burst that's affectionately named Candy. Photo by Dillon Stewart

After a move to Phoenix, he marked time with his own trio but couldn’t break through the insularity of the local blues scene, so in 2006 he chucked it all and headed east to Nashville. “I had no money and nothing going,” he says candidly. “And right about the time I was ready to pack it up and leave again—because I was failing, miserably—Don Kelley gave me an opportunity.”

A fixture on Nashville’s lower Broadway strip since the early ’80s, the Don Kelley Band is a proving ground for new talent in a city that’s teeming with hot players. Kelley’s lead guitarist at the time, Guthrie Trapp, was fixing to strike out on his own, so the search was on for his successor. “The timing was right,” Simo says, “but I’d never played that style of music before in my life—you know, Western swing, million-mile-an-hour bluegrass [laughs]. But I had to survive, and Don gave me a chance with a very good paying gig. And from that, I got my foot in the door with producers to start playing on records.”

An impromptu but lively jam with Abrashoff and bassist Frank Swart inspired the three to join forces as SIMO in 2010. A well-received debut album followed. The trio barnstormed around the U.S. for several years until Swart bowed out of the grind, but the hiatus was short-lived. In early 2015, Shapiro came onboard, and now a resurgent and fully recalibrated SIMO is locked and loaded.

The band’s latest album is a loud, brash, and brave testament to the rewards of blazing your own path—not to mention a hard-chugging, blues-rock freight train of feverish improvisation. Incredibly, Let Love Show the Way started out as a filler session to record some bonus tracks for an existing album SIMO had already delivered to the label. Two days later, they had another album’s worth of material that compelled Simo, the producer, to rethink the entire project.

Of course, the environment might have had something to do with it. Not only was Simo playing Duane Allman’s original ’57 Les Paul goldtop, but the band was tracking at the fabled Allman Brothers retreat in Macon, Georgia, known far and wide as the Big House [see sidebar, “Let It Bleed”]. There’s a trenchant, touching, and soulful aura that seeps through the “No Way Out”-like boogie of “Stranger’s Blues,” the Zep-soaked hard rock of the title track (replete with cavernous wah and slide solos), the pastoral acoustic blues of “Today I Am Here,” or the extended freestyle psych riffage of “Ain’t Doin’ Nothin’.” Cut live with very few overdubs, Let Love Show the Way comes across as a throwback to how rock albums in the late ’60s and early ’70s used to be made.

After a recent hop across the pond to Europe, SIMO is gearing up for a slew of U.S. dates into the spring. Meanwhile, Simo’s profile in Nashville is on the rise. He recently did a session with Jack White at his Third Man Studios, and he has a lot more in store for 2016.

Simo plays old Marshalls with nothing between him and the amp. “You almost have to block the waves with your body to control the guitar so it doesn’t just howl and run away from you,” says the 6-string virtuoso.

Photo by Derek Martinez Photography

How did you get your hands on Duane Allman’s Les Paul?

My relationship with Duane’s goldtop goes back several years to the Don Kelley Band. I met the owner of the guitar back then. He came to see me when I was with Don, and I became friends with him. I had no idea he owned Duane’s guitar—I found out later, of course—but he’s a collector in Florida, a real gracious gentleman. When the band first played in Macon, Georgia, he let me play it then. That was the first time, and since then I’ve played it many more times.

What are some of the particulars of that guitar?

Well, from what I understand, it’s been refinished twice since Duane had it, and the pickups aren’t the originals. He took them out to put in the ’59 ’burst [sunburst] that he used on At Fillmore East, which is what he traded the goldtop for. So I believe the pickups are PAFs from a [Gibson] Byrdland.

I’ve been lucky enough to play a lot of vintage instruments, and the neck on it is very peculiar. I hate to compare it to something, because one of the misnomers in the vintage world is “Oh, it’s a neck like such-and-such,” but every one of them is different. It feels much more like an early ’60s Gibson. It’s slimmer, and the profile is very unlike what it’s supposed to be. So I don’t know if the neck has ever been worked on, but the profile is very different from other ’57, ’58 goldtops I’ve played.

Overall it’s probably eight pounds and change, so not too heavy, but not too light. It’s also very resonant and the pickups are very microphonic, which I like. I play through old Marshalls with nothing in between me and the amp, and if you see footage of guys who used that rig—which everyone did in the late ’60s, right?—you almost have to block the waves with your body to control the guitar so it doesn’t just howl and run away from you. These days, no one would stand for that [laughs].

But to me, with all those harmonics happening, you can get the guitar to do things that no amount of pedals on the floor can do. The treble pickup on that one in particular is extremely microphonic, so it’s really fun to play. For the sessions in Macon, it just clicked. I don’t know if it was how we had it set up, but it was really getting a great sound.

So you pretty much replicated your live sound for the album?

Oh yeah—the only difference obviously is that I don’t always get to tour with Duane’s guitar [laughs]. I have a 1960 Les Paul ’burst called Candy that’s been on permanent loan, if you will, to me for about a year-and-a-half, and that’s pretty much been the guitar that I’ve settled on playing the majority of the time. The Les Paul body style is just very comfortable for me, and playing slide is very easy for me up high, beyond the fretboard.

But besides Duane’s goldtop, on the album I played a ’58 Flying V on “Long May You Sail,” and then on “Becky’s Last Occupation,” which we actually cut at a small studio in Nashville, I’m playing two guitars. The main one is the ’60 ’burst, and the overdub is another guitar that was loaned to me at the time, which Joe Bonamassa owns now—a ’59 ’burst called Linny. I just plugged it straight into a Universal Audio mic pre and distorted that, so it sounds like a fuzz.

JD Simo's Gear

Guitars1960 Gibson Les Paul sunburst

1959 Gibson Les Paul sunburst (studio)

Duane Allman’s 1957 Gibson Les Paul goldtop (studio)

1962 Gibson ES-335

1958 Gibson Flying V

Amps

1969 Marshall Super Lead

1969 Marshall 4x12 cabs (with “basket weave” grill)

Effects

1968 Vox Cry Baby wah

Marshall Supa Fuzz

Farmland FX SIMO SupaFuzz

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXL120+ Nickel Super Light string sets (.0095–.044)

Dunlop Herco Flex 75 picks

Vintage Coricidin bottles (for slide)

I used the ’69 Marshall [Super Lead] pretty much on everything, with the exception of “Stranger’s Blues”—that’s actually an old Traynor YGM Guitar Mate combo. With the Marshall, I just turn it up all the way and use my volume and tone controls, and I pretty much set it the same way. I know from years of doing this—it’s loud, but I think until you’ve really had the opportunity to play through an old Marshall stack that’s set up right, it’s a loud that is very different from what people have become accustomed to. It’s a warm, percussive, sweet sound—not piercing or aggressive or annoying. It’s a very inviting, enveloping thing.

I mean, I’m a little louder than the drums, but it depends on the situation. Sometimes I’ll just run through one cab, and sometimes I’ll pull two of the tubes so the amp runs at about 65 or 70 watts. I know how to do all that stuff—to me it’s like working on my car. I’ll re-bias it and set it how it needs to be. It doesn’t knock the volume down that much, but it changes the way it feels. [See Simo’s 2014 Rig Rundown for more details on how he maintains his Marshalls.]

And one thing I’ve learned from years working on records: The smaller the amplifier, the closer you can mike it and get it to sound great. But if you close-mike a big amplifier like it’s a Princeton, it’s gonna sound small. You have to allow the sound wave to travel a little bit so it can fully develop. If you look at old photos, it’s not something I came up with. Any photo of Hendrix or Zeppelin or the Allman Brothers or even Michael Bloomfield recording Super Session, the mic is about a foot away—sometimes more. It’s pretty simple; you move the microphone around, and you find what sounds good.

What drove you to expand the Big House session into a full-blown album?

We got the three things done that I needed right away, and it was going so strong that we just kept working. That’s where experience comes into play. Before we went in, I’d had the guys over a lot and we were very well prepared, so I knew if it turned out that way we wouldn’t get caught with nothing to work on. And it was one of those things where the performances were so good and so inspired, it was like, “Let’s just keep going.”

You jumped ship from a pretty solid and structured gig with Don Kelley, and made a leap into the unknown. How did you deal with that transition?

If what you do is make music, and people are paying to come see you play or are going to buy your record—well, it’s a perpetual motion thing. If you’re blessed enough to be able to have success, it’s even harder to hold on to it, let alone get it in the first place. And to me, that’s the beauty of improvising the jam element, because it’s like, hey, if you dig what’s going on, great—come hang with us. The music that we make is what feels natural to me, and always has, in one form or another. But at the same time, improvised music can be as avant-garde or as rigidly structured as you want. I just love the language of improvisation and I had to make a whole paradigm shift in my life to be able to get to where I am now. I’m sure anyone can relate to that, who’s had to work to get somewhere. Nothing makes it harder to go back to zero than when you’ve had a taste of something. Your sense of entitlement can stand in the way—but nobody owes you anything, man! You gotta do the work, because it’s all part of the journey.

YouTube It

JD Simo enlists the help of Tommy Emmanuel on a Telecaster for “With a Little Help from My Friends.” Simo puts down his Les Paul and opts for a Flying V on this one. Witness Emmanuel and Simo trade solos for nearly 3 minutes from the 6:30 mark onward.

You’ve talked about how much improvisation means to you. Who influences you the most when you’re exploring those edges?

Well, the original Allman Brothers Band when Duane was alive is a huge influence, not only on myself but on all of us in the band. To me, within rock music—that’s the thing. We play blues, but I really look at it as a rock band. And within the lineage of what I think of as rock bands who truly improvised, obviously Cream and Led Zeppelin and the Grateful Dead did a lot of it, but for me personally, I don’t think anyone has improvised better than that original Allman Brothers Band. You’ve got six guys who were able to rise and fall dynamically, stop, go to nothingness together—it was just beautiful. I don’t think it’s ever been done better, before or since.

You’ve also said you’re a fan of the feel of guys like Free’s Paul Kossoff or Mike Bloomfield.

I definitely try to keep my foot in that place. That emotion is generally what I love, and what really grabs me. I always want to continue to try to push myself, but at the same time, I don’t feel like anyone can ever master the beautiful simplicity of a player like Koss or Bloomfield, let alone the ones who started it, like B.B. King, Freddie King, Albert King, John Lee Hooker, T-Bone Walker, or Hubert Sumlin. Koss is a perfect example of someone who’s playing in a very easy-to-understand language, but the way he played it was so passionate and beautiful. You can spend your whole life and never reach the end of that simple language.

SIMO is, from left to right, drummer Adam Abrashoff, guitarist and frontman JD Simo, and bassist Elad Shapiro.

Let It Bleed

Does the “vibe” of a place come through in a recording? Just ask Jimmy Page about Headley Grange (where most of Led Zeppelin IV and Physical Graffiti were tracked), or Rick Rubin about the Harry Houdini mansion in Laurel Canyon (site of the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Blood Sugar Sex Magik, among others). Last summer, when JD Simo and engineer Nick Worley found themselves walking through the Big House—once the unofficial residence and now the official museum of the Allman Brothers Band—their first thought was, “Wouldn’t it be cool to record here?”It didn’t take long to work out the logistics, and soon Worley had cobbled together a mobile studio to make the 300-mile trip from Nashville to Macon. “It’s a huge house with tall ceilings and wood floors,” Worley says, “so we knew it would be a nice place to record. We put the drums in the big foyer right in the front, with a staircase that goes up three stories, and set up some baffles. JD and Elad were basically standing right in front of the drums, and they each had an amp nearby, in separate rooms. There was still plenty of bleed going on in the overall picture, but it helped us manage it a little bit.”

Setting up his Pro Tools-based “control room” in the kitchen where Dickey Betts wrote “Ramblin’ Man,” Worley miked the band with a nod to the spare miking schemes of Glyn and Andy Johns. Simo’s Marshall stack had a Cascade Fat Head ribbon mic on one of the cones from a few inches away, but the amp room also opened up onto a smaller room, where Worley placed an Ashman Acoustics SOM50 SuperOmni to capture the atmospherics.

Simo usually plays his Marshalls turned up all the way, using the volume and tone controls on the guitar to adjust his distortion level. He rarely has anything on the floor, other than a wah pedal or the occasional fuzz effect. The idea is always to let the amp determine the sound, but as Simo explains, the wide-open layout at the Big House added a lot to the overall spectrum.

it was just beautiful.”

“I was able to walk into the other room to get feedback if I wanted, and the external room ended up being essentially a reverb chamber for the guitar. My vocal mic was set up with a shield around it, to get as much out of that as we could, too. That’s where some of the murkiness of the album comes from, but that’s the price you pay for all that bleed.”

Although Simo recut a substantial amount of his vocals, quite a few of them ended up in the final mix—again, with the requisite bleed. “We’re not gonna win a best engineering Grammy for this thing,” Worley jokes, “and if we did, we probably did something wrong. This record is really about the spirit of the players in the room together, and the magic and the little accidents that happen. It’s much less about ‘Let’s fix everything and make it perfect, and let’s show everybody how great we are with our technical skills.’ It’s more about getting a real vibe going, getting a great take, and everything else be damned. Once you have that magic take, that’s your keeper, and except for mixing it, it’s pretty much already there.”

In the mix, Worley would sometimes brush the guitars with a Universal Audio 610 for compression, but usually just to roll off a bit of low end to keep out the extra room noise. “Those loud Marshalls kind of compress themselves,” he says, “so if you look at a rhythm track digitally, it comes through nicely squared-off, but it’s a nice fuzzy, caterpillar-looking thing. When JD does solos, we’ll end up hitting that with some compression, but as a rule I don’t really use it that much.”

While the old-school approach—stripped-down miking, lots of volume and tons of bleed, all tracked in a big old creaky house—might seem like overkill, there’s clearly a method to SIMO’s madness. “This is a very vibe-oriented band,” Worley observes, “so if anything is off at all, they’ll just move on to the next thing. It’s old-school, but it’s not like a Civil War reenactment. JD is bringing his own thing to the table with it—his own melodies, his songs, and his voice. So it’s not like we’re just trying to remake old records. He’s definitely got his own thing; it just so happens that the recording methods of those years fit the music much better.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)