South by Southwest is the festival whose “best-of” lists you should view with the most skepticism. More than 2,000 acts played its official events, and it’s impossible to tally how many more performances were staged in the warehouses, parks, and dives of East Austin. One could go on a live music bender and see bands play non-stop from 11 a.m. to 2 a.m. (or later), Tuesday through Sunday, and miss 98 percent of them. So, this list acknowledges James Williamson, Rick Nielsen, and the thousands of other players unseen and unheard by many attendees.

It’s worth repeating that yes, it is actually possible to see bands play non-stop and around the clock for the entire week of SXSW. Perhaps not if you wanted to emerge with your feet, liver, ears, and brain intact, but you could do it. Or, you can remain unscathed, save your health, and just read about eight of the best players we saw this year.

Photo by Daniel Muller, hearnebraska.org

Jim Schroeder, UUVVWWZ

UUVVWWZ can’t be an easy band to play guitar in. The rhythm section is groovy and skilled, but on many songs, it’s a closed system that doesn’t have room for a guitar to ride along with it. Meanwhile, singer Teal Gardner covers a wide range and sits at the top of the mix, as she should.

You can imagine how a lesser player might try to fit. It would be tempting to hang back a lot, and equally easy to overplay and get in Gardner’s way. A guitarist could simply be a counterpoint to her, playing melodies in between the ones she sings.

With the exception of some well-chosen silences, Jim Schroeder doesn’t do any of these things. He’s the most dynamic player in a dynamic band, employing muted riffs, percussive rhythms, and massive distortion, depending on the moment. He switches quickly between these and other techniques within songs, and makes it look as though they’re all natural, intuitive ways for him to play. His variety is chosen well, though: a quiet two-note riff played at the beginning of a song might be reprised as a wall of sound at the end.

Schroeder plays the guitar he wanted “really bad in high school”—an Epiphone Dot LE. He’s had it for 11 years, and it’s now his only guitar. “I think it’s good for sustain,” he says, with “a really dark, low, mid-range-y tone, which I am just really drawn to.”

A surprising feature of this band’s show was interpreter Chelsea Richardson, a longtime friend of Gardner’s who signed the lyrics from the stage. Standing next to Gardner and dancing gently, her movements were so fluid as to make her seem like a natural extension of the band.

Watch UUVVWWZ at SXSW 2013:

Christian Lee and Octavius Nebeaux, Dolores Boys

The Dolores Boys, Christian Lee and Octavius Nebeaux, are hardly the first to send their Telecasters through a laptop—nor the first to strum with a drumstick. But this didn’t turn out to be a performance suspect of email checking or pretense.

Instead, Lee rocked out. His singing—barely decipherable, yet smart and as visceral as the music—alone would differentiate him from the masses of less extroverted guitar processors. He goes further, letting the music shake him, occasionally even out into the audience.

A tiny theater with eight people seated might not sound like the perfect venue for the Dolores Boys’ performance, but it was. A band this amplified, in which Nebeaux’s every touch and slight scrape of his strings barreled out of the P.A., was further illuminated by the dimly lit, silent surroundings. When they were loud (which is most of the time), it was hard to tell who was making what sounds. In general, though, Lee sang, played the faster riffs, and started the tracks on the laptop. Nebeaux seemed like the more amplified, droning player, and also had a small drumset at his disposal.

“He’s actually a really great guitar player,” Lee says of Nebeaux. “Folk, blues, anything. He could sit down and you’d think he was the greatest guitar picker, and that that’s all he does. I think we [both] come from a pretty wide range of intense, strange, beautiful music.”

Watch Dolores Boys at Philadelphia's Random Tea Room, October 2012:

Bradley Fry, Pissed Jeans

A relentless juggernaut revved to full-throttle with fuzz and reckless abandon … that’s Pissed Jeans. “I’ve always been super sloppy,” Bradley Fry says of his guitar playing. “I have really small hands, so I can’t play super fast or anything like that. I figured instead of trying to play like somebody else, let me play how I play, and write songs to fit with that—embrace feedback and that sort of stuff.”

Fry sells himself short, but deliberately unkempt was certainly his method and the band’s, as they didn’t plan a setlist but charged right through. Fry had a great, sludgy tone reminiscent of Greg Ginn circa 1982, and put it to work at sharp riffs with plenty of feedback. His right hand never seemed to hit the strings the same way twice, flailing back and forth yet somehow holding down a melody.

“You want it to have some sort of spontaneity to it, versus everything being planned,” he adds. “It’s just what feels like coming out.” On the recent Pissed Jeans record, Fry did most of the solos in one take. His philosophy was: “Let’s just do it, record it, boom. ‘Was it horrible?’ ‘No?’ ‘Okay, keep it.’”

On the other hand, he’s found it hard to recreate those solos, he says, played through two favorite amps—including a Peavey Renown 400—and two cranked fuzz pedals, at shows. This was apparent in Austin, where his excellent riffs and their devil-may-care strumming, not the solos, were the highlight.

Fry generally plays Jaguars and Jazzmasters, but at Austin’s 1100 Warehouse, he played a Godcity guitar that Kurt Ballou built with three different P-90s and phase switching, allowing at least a dozen pickup combinations.

Watch Pissed Jeans at their record release party at Philadelphia's Underground Arts, February 2013:

Brooklyn Vegan held a two-stage, one-queue event at the space formerly occupied by 6th and Red River stalwart Emo’s. While Nashville metal trio Today is the Day played for a sparse crowd at “The Jr.” (the indoor space), Dallas non-metal concern The Polyphonic Spree entertained a capacity crowd in the larger area, leaving a handful of Today is the Day fans waiting outside for indie pop fans to exit. Fortunately, those in charge recognized the jam and let the metal folks advance to the small room.

Like his band, Steve Austin’s playing is kinetic. He wasn’t trying to win a shredding contest on the Jr.’s stage, and he probably wouldn’t. That’s beside the point. This metal band deals in volume, heaviness, and intensity, but they’ve always delivered these staples with varied rhythms, tempos, vocal styles, and even instrumentation, replacing bass with keyboards and samples on 1996’s self-titled LP.

Bassist Ryan Jones’ sound is just dense enough that Austin can solo without making the music sound thin, but he generally didn’t. Instead, he favored short fills and leads that often joined drummer Curran Reynolds in transitions, rather than grabbing the spotlight.

Dripping with sweat, Austin played and sang his agonizing songs with total sincerity and intensity. Frankly, songs like these would sound pretty corny otherwise, but he nailed it. He quarreled with the soundwoman throughout the set, perhaps grist for his mill, and he finished the show by snapping all the strings on his black beater PRS.

Watch Today is the Day at SXSW 2013:

Patrick Higgins, Zs

Despite what’s written above about the relative unknowability of SXSW, for the sake of this article and the scope of performances seen, it wouldn’t be entirely unreasonable to name Patrick Higgins the best guitarist of the 2013 event.

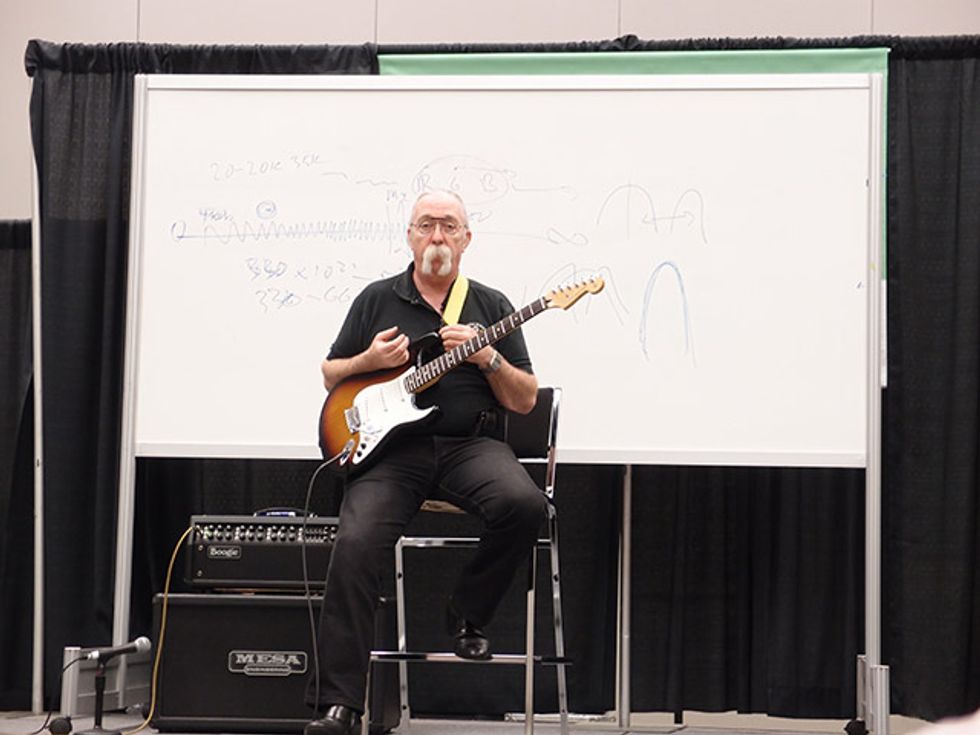

By some combination of talent and a well-conceived rig, he makes breakneck playing look effortless. He’s sending two signals from his sunburst Fender Strat, each controlled by a volume pedal. One goes to a laptop with a delay he programmed in Pure Data, which sends stereo outputs that sound back and forth, and the other goes to a rack of analog pedals that he uses for pitch shifting, oscillations, and more extreme manipulations.

As for talent in style, it’s almost suspenseful how he adjusts his voicing and changes up the delay on his riffs. Drummer Greg Fox and saxophonist Sam Hillmer are skilled in issuing nearly as many tones as Higgins does. It’s a super agile band all around, and though it’s odd to say a band so busy is restrained, they certainly are. Many minutes into their compositions, Higgins does indulge in some satisfying, beefy, major-chord breaks, but they don’t feel obligatory or out of place. They take the music somewhere, and are usually good riffs themselves.

Though Higgins had an ordinary path to weird music, it was an accelerated one. He says he started playing at 9 and quickly got into blues, rock, and heavy metal, had his punk phase at 11, and then by 12 began to study and play jazz and classical, which he stayed with through college.

He’s had his chair in Zs since 2012, when he replaced another great player, Ben Greenberg. “It’s a little easier,” Higgins said of the trio’s preference for sitting while playing, “and I think the idea is also to take focus away from people roaming around stage and detract from the physical presence of the performers a little bit. Help the audience focus in on the sounds and less the performance gestures.”

Watch Zs at SXSW 2013:

However cheesy, Jeff Baxter’s “POLICE LINE – DO NOT CROSS” guitar strap is appropriate. After a successful career playing guitar in Steely Dan, the Doobie Brothers, and numerous sessions, he became an in-demand consultant to the Department of Defense, Congressman Dana Rohrabacher (R-CA), and various defense contractors.

Now, this wasn’t an entirely non-musical career change, like those made by James Williamson and Santiago Durango. In the 1980s, Baxter became interested in military developments like high-capacity storage devices and data-compression algorithms for their music recording applications. His monologues on physics, his defense work, and music comingle freely. And, as the Wall Street Journal reported in 2005, he still dresses for work like a session guitarist, even in a world of stern ex-military men.

Baxter’s talk was more focused on basic physics than on military applications, or musical applications for that matter, and his Strat began to seem like an unwieldy, needless prop. But it’d be silly to evaluate the lecture by any conventional public-speaking rubric. When you have a man with a white trucker moustache and ponytail who ‘s been a member of associations with names like “Ultimate Spinach” sitting on a stool, lecturing a crowd at an event that costs hundreds of dollars to enter about whether Native American drum circles prevent illnesses, it hardly matters that he’s wearing a sunburst Strat.

Questions ranged from whether tape still exists of the full outro guitar solo from “My Old School” to whether there is a particular frequency that will destroy tumors. Baxter also had a question for the audience. “Did anybody bring a guitar?” No hands rose. “Nobody brought a guitar?” Still no one. Feigning disappointment, he claimed that in five minutes he could have turned any one of us “into a great bebop jazz player.”

Marnie Stern’s show could be a challenging one to mix. Her guitar parts are mostly composed of either high-register fingertapping and tremolo, or loud power-chord breaks. Her singing mirrors the former: soprano and staccato. Meanwhile, she’s backed by busy drums and Nithin Kalvakota’s loud, thick bass.

Point being, it’s easy to see how her quieter, thinner sections could get drowned out, either by the rhythm section, her own vocals, or by being mixed at chord volume. In the joined, sprawling backyard of Eastside bars Hotel Vegas and The Volstead, it often did. It was one of 10 shows she played at the festival, and she notes that “There’s no way to do soundchecks at SX.”

To her credit, she gave her Jazzmaster’s fretboard a major workout. Bad sound at a shoegaze show, or anything with two or three guitarists, could sink the thing, but in addition to being funny and magnetic, she has a style that’s energetic and physical enough that you could easily follow along. Well, it’s also kind of bizarre, so maybe “follow along” isn’t the right phrase. It would be more apt to say that Stern is engaging and knows how to keep an audience’s attention. What’s impressive is that she alternates fluidly between her various techniques without making the songs sound disjointed or gimmicky. She convinces you that tapping frets while ooh-aah-eehing into the microphone is a normal and good way to play rock songs.

Watch Marnie Stern at SXSW 2013:

You could easily be a fan of Chapel Hill’s Spider Bags for years without knowing what a great player frontman Dan McGee is. He didn’t need to be when he had Gregg Levy (“great at coming up with countermelodies,” McGee says), Rob DiPatri (“never goes for the easy path”), and/or Chris Girard (“one of my all-time favorite guitar players”) backing him.

Now that the band’s down to a trio, McGee’s risen to the occasion. He still downstrokes his guitar like he did when he was the rhythm guitarist, but his style’s gotten bluesier and more fluid. “There has to be rhythm guitar,” he says, “there also have to be countermelodies, and I also have to do the best I can with my vocal instrument, which is not my strongest point.”

Admittedly, his singing is probably third behind his occasionally excellent lyrics and his very good guitar playing—but he’s let humility get in his way in the past. Back when he was the more rudimentary guitarist in the band, sometimes he’d nonetheless play at full blast while singing passively, completely obscuring the lyrics with the guitar.

Whether due to the quieter nature of his current playing style, the backline, or a conscious shift, you could hear everything well at the Saturday afternoon Beerland show. Though the band was sweaty and energetic, McGee says they were getting fatigued. They played a show a day from Wednesday to Sunday (backing off from two or three a day in recent years). “The Sunday was like a locals one,” he says, “and I knew it was a crowd that was already into the band.” Saturday, then, “was the last time I felt like I had to, like, prove it to a new audience.”

McGee saw a chance for a funny breather-as-stage-move during the closer, “Shape I Was In” from last fall’s Shake My Head. During the instrumental break preceding the final solo and double-time chorus (“you need a lot of breath for that”), he hopped offstage, and the crowd parted as he lay down on the Beerland floor. “I was like, we’ve got one more chorus after this,” he remembers, “I’m just going to lay down for a minute, play this little guitar solo and take a breather.”

Watch Spider Bags in Philadelphia, January 2013

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.