When Daniel Donato was 12, he heard “Paradise City” by Guns N’ Roses for the first time. He’d been living in Nashville since he was 7—his family had moved there from New Jersey, where he was born, after his father got a good-paying IT job with Davidson County in Tennessee—and he was just starting to become completely obsessed with guitars, guitar players, and guitar music. “I heard this certain part in the solo,” Donato recalls via Zoom from his perch in the back of a tour bus cruising through the mountains of Montana, “when it’s going into double time and Slash is hitting this….”

At this point, words fail and only scat, accompanied by enthusiastic hand-miming over a ghost fretboard, will do. “Doodala-doodala-didala-doodala-didala-doodala-daaahhh.…” He leans closer for a second, peering deeply into his phone screen to add, “It’s on the neck pickup,” then resumes his previous position. “I remember looping this piece of audio over and over because it was such bad-ness. It was like, how could a guitar possibly do that?”

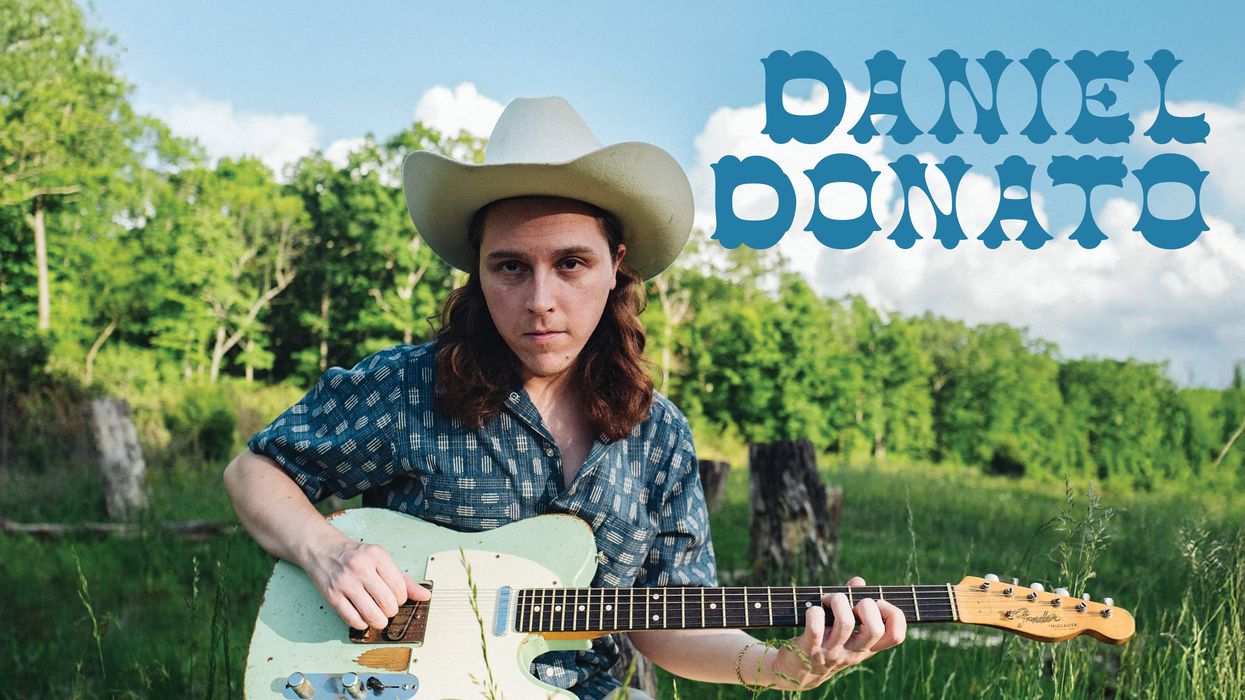

Fast forward 18 years to 2025. Donato was working on his third full-length album, Horizons, with his band Cosmic Country at Sputnik Sound in Nashville. Two of the album’s most striking songs, “Chore” and “Down Bedford,” start out sounding like standard country tunes, but, over their considerable lengths (more than 11 minutes for “Chore,” almost 10 for “Down Bedford”), they morph into something more akin to prog or fusion, with dramatic time signature changes, dynamic shifts, and utterly commanding guitar solos. Think of Steve Morse’s work with the Dixie Dregs and you’ll be in the right ballpark. Sitting in the control room listening back to the final takes of these songs, Donato had a realization: He was reaching a level of musical energy he’d considered impossible as a preteen listening to Slash’s “Paradise City” solo. “I thought, ‘I’m kinda doing that,’” he says.

Donato isn’t bragging when he says this. There’s a big smile on his face, but his voice is infused with a humble awe that borders on disbelief. “It’s something that, at one point, I really prayed and worked hard to be able to do,” he says. “And now I could do it.”

Daniel Donato didn’t just achieve mastery of the guitar this year. His way with a Telecaster has been evident since at least his debut EP, 2019’s Starlight. But Horizons does bear all the signs of an early career milestone. It shows him finding his voice as a songwriter, somewhere in between the twang of Mickey Newbury and the grit of Robbie Robertson. And it’s the sharpest presentation yet of his own signature sound, which occupies the sweet spot where Americana, outlaw country, modern country, and jam-band music meet.

“I felt like I knew Jerry [Garcia] because I had the same desire, and he was giving me permission to do what he did, but in a way that was my own.”

Donato remains far from satisfied, however; he’s set his sights on something even bigger. “I’m still working on this one goal that I’ve had since I was 14 or 15,” he says. “You know when you can hear a single note from a player and you know who that player is? You can do that with Django [Reinhardt], with Jerry [Garcia], with Willie [Nelson], with all the greats. That’s my goal. If you can hear one of my notes at, like, 15-percent volume and know that it’s me, and that knowledge elicits a positive emotional response … that’s my number one, still.”

Funnily enough, Donato’s quest for individuality started with the video game Guitar Hero. “I loved playing it,” he says. “I loved practicing the game. And then, all of a sudden, one day I was like, ‘Man, I just want to play guitar.’ It really was that childlike and that simple.” Luckily, he already had an instrument on hand; his music-loving father, who was to become his first guitar teacher, had given it to him as a Christmas present several years earlier. Up until then, he’d barely touched it.

Dad did his job well. Within two years, Donato was busking on Lower Broadway in Nashville. And within three years, he was playing professionally with a local group called the Don Kelley Band and made it through the doors of Robert’s Western World, one of Music City’s few remaining genuine honky-tonk saloons, where his apprenticeship began in earnest.

“Robert’s is truly the home of traditional country music,” Donato explains. “When you go in, there are photos of Tom T. Hall hanging out there, of George Strait and Merle Haggard and Charley Pride. That building is where the pedal-steel guitar was invented. It’s where Willie Nelson bought Trigger. And it’s just a living testament to the spirit of that music. But what it is now is way different than what it was when I started going. It was only busy from 6 p.m. to closing, and then from 10 a.m. to 6, there would be these Western-swing bands that would play. All these musicians would pull up, park their cars right out front, and just go in”—unimaginable in today’s tourist-mobbed downtown.

“These were guys that played on the actual records that were being covered there,” he continues. “Amazing pedal-steel players and fiddle players that used to tour with George Jones and Merle and David Allan Coe and Johnny Paycheck, and they were just there playing for tips, picking into a Peavey solid-state amp and drinking a Budweiser. And I’d go see these guys every week and learn from them. Sometimes, once I’d gotten to know them, I’d go over to their houses and ask them, ‘What was that thing that you were doing over A7?’ and they’d say, ‘Well, I’m playing Em7 over A7, and that’s a substitution.’ And I’d be like, ‘What’s a substitution?’ It was all one-on-one. I travel this country a lot, I see a lot of places and people and music, and I haven’t seen a place like Robert’s, the way it was then.”

“I loved practicing [Guitar Hero]. And then, all of a sudden, one day I was like, ‘Man, I just want to play guitar.’”

Soon, Donato was taking private lessons with the likes of Brent Mason and Johnny Hiland, supplementing what he learned there with Advanced Placement music theory classes, and delving deep into the history and techniques of country music.

“Grady Martin and Hank Garland and Leon Rhodes, who played with Ernest Tubb for a long time, and Spider Wilson, the Grand Ole Opry’s house guitar player—they all played jazz,” he notes. “They loved Charlie Parker. They were copping Charlie Christian lines, and they were all doing that style on hollowbody guitars.

Daniel Donato’s Gear

Guitars

Two DGN Custom Epoch semi-hollow three-pickup T-style electrics

Fender Custom Shop Telecaster

Tangled String/Danny Davis custom 00-size acoustic

Amp

1966 Fender Pro Reverb

Effects

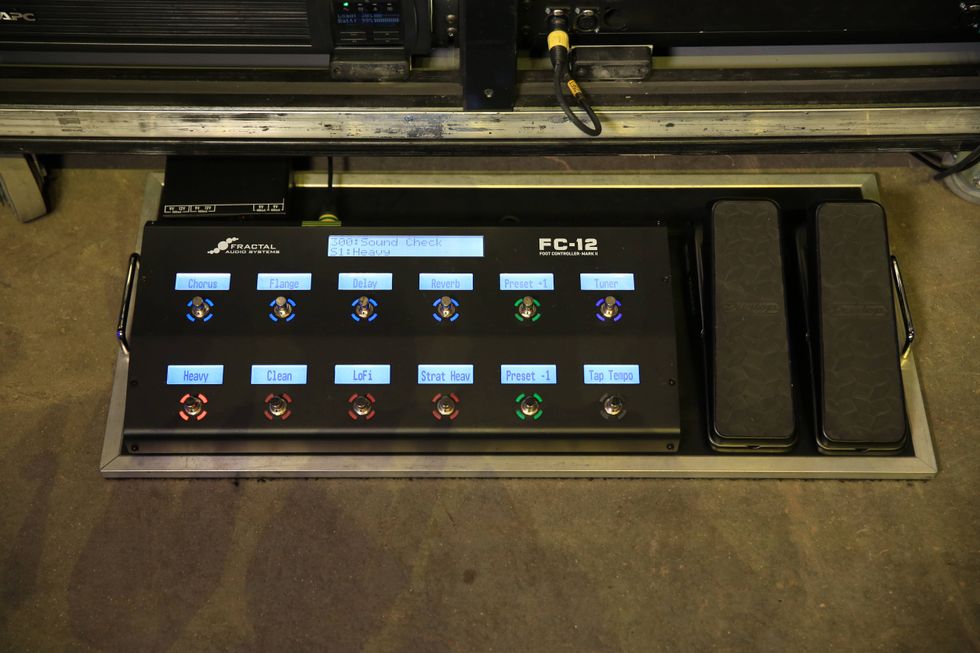

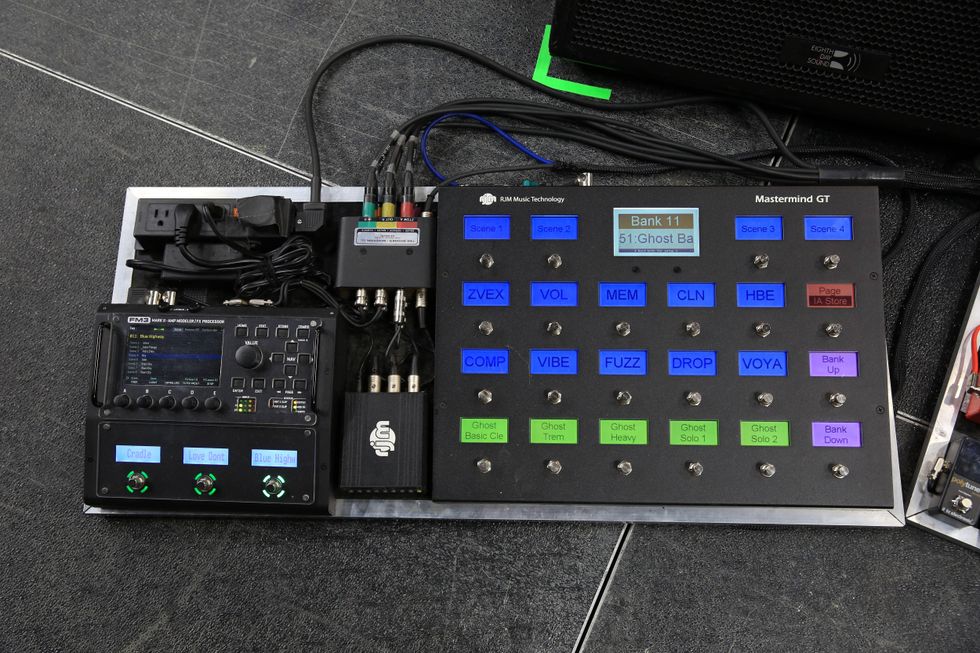

Universal Audio Max preamp/dual compressor

Keeley Rotary

Keeley Cosmic Country phaser

Keeley Manis overdrive

Keeley Noble Screamer overdrive

Walrus R1 reverb

Strymon Timeline delay

DigiTech FreqOut

Eventide H90 harmonizer

Dunlop expression pedal

Gamechanger Audio Plus sustain

Fender Tone Master Pro multieffects/amp modeler

Strymon power supplies

Strings, Picks, and Cables

Ernie Ball Cobalt Slinkys (.010–.052)

Dunlop acrylic picks

Mogami cables

They weren’t even playing Teles. And a lot of that history transitioned into the era of guitar players that I learned from, like Brent, who loves George Benson, who loves Jerry Reed—and Jerry Reed played with all those old Nashville jazz cats. There’s a lot of guitar players in Nashville who’ll do, say, a Phrygian dominant substitution over a dominant-seventh chord on a honky-tonk tune. And it’s truly Nashville, in a way that only like 30 people know.”

Donato announced his intention to join that lineage early on in his recording career. At one key moment in his blazing solo on “Meet Me in Dallas,” from his first full-length, A Young Man’s Country (2020), he repeats a high C major triad over F and E flat chords, a cool extension of the harmony that immediately thrills the ear. Hank Garland would be proud.

“Amazing pedal-steel players and fiddle players that used to tour with George Jones and Merle and David Allan Coe and Johnny Paycheck … were just there playing for tips, picking into a Peavey solid-state amp and drinking a Budweiser.”

The next foundational piece in the Daniel Donato puzzle fell into place when he was 17, playing regularly at Robert’s Western World while still in high school. At 7:30 one Thursday morning, his U.S. history teacher asked for a brief private audience after class. When class ended 45 minutes later, the teacher pulled three huge binders from behind his desk. As Donato remembers it, “He said, ‘I saw you last night at Robert’s with my fiancée, and I want to give you some music that I think you’ll like.’”

In those three binders were more than 200 CDs, all featuring music either by or related to the Grateful Dead. “It was 35 volumes of Dick’s Picks. It was the Jerry Garcia Band through every era. It was Jerry’s duo with [upright bassist] John Kahn. It was Legion of Mary [Garcia’s band with keyboardist Merl Saunders]. It was The Pizza Tapes [which Garcia recorded in 1993 with bluegrass musicians David Grisman and Tony Rice]. It was The Phil Zone [a collection of vintage Dead live recordings chosen by bassist Phil Lesh]. It was everything possible.”

Donato was familiar with the Dead to some degree—his mom was a fan and his uncle had dropped out of school to follow them around the country in his youth—but this was a far deeper immersion. The first disc he put on was Dick’s Picks Vol. 3, recorded at the Hollywood Sportatorium in Pembroke Pines, Florida, on May 22, 1977. “That has a great version of ‘Big River’ on it,” he says. “I played ‘Big River’ with Don Kelley, and I always loved that song. When I heard the Dead play it, I was like, ‘Oh man, this song could be more than four minutes long. It’s okay to hang on the A for three minutes on the intro.’ And that, to me, was something approaching a revelation: how you can take country tunes and kind of dance around them. I felt like I knew Jerry because I had the same desire, and he was giving me permission to do what he did, but in a way that was my own.”

Donato’s latest, Horizons, is his third full-length effort and features his Cosmic Country band.

There’s no question that you can hear Garcia in Donato’s style: the long conversational solos, the playful use of arpeggios, the fondness for effects pedals—like the octave, the envelope filter, and especially the phaser—whose tones hearken back to the country-rock of the ’70s. (Although Donato points out, rightly, that the phaser was at one time a fixture of mainstream country as well: “Back in the day, all the Nashville cats would have a Maestro or MXR phaser and they’d turn it to where it’s pretty much just like a level boost. It’s barely on. That’s a real old-timey, traditional use of the effect.”)

Still, the Dead’s impact on Donato goes well beyond sound or improvisational approach or even musical qualities of any sort. The example they set as performers has helped guide him toward a way of presenting himself to the world, and the marketplace. Look at his Bandcamp page and you’ll see for sale complete recordings of every concert he’s played for the last several years. It’s a tactic that feels both generously fan-centric and cannily entrepreneurial. It also makes one think of Dick’s Picks and The Phil Zone in the way it builds a mystique around the live experience.

“There’s American bands by musical nature and then there’s American bands by functionality,” Donato posits. “And the Dead were both of those. They strived to keep ticket prices low. They played venues that they didn’t care if they didn’t sell out, because they wanted everybody to get in. They would change the set list every day because they wanted to cater to the people that were in their community. And they would give away their music [letting fans tape the concerts and then circulate the tapes among themselves]. I really like that [David] Letterman interview when Jerry said, ‘We’re done with it. It’s theirs.’ There’s a free-market element to that that’s uniquely American. And it definitely informs the ethos of Cosmic Country, in a big way.”