Picture this: You’ve been tapped to play a small stage for a date on the Warped Tour. You find out that you’ll be on at around 4 p.m., and your band is slotted third in a lineup that includes seven other groups. You think, “How could they possibly turn the stage over between each band swiftly enough to make every set happen on time?” That’s where a backline comes in.

At some point in your gigging life, you can likely expect to run into a situation where you’ll be plugging into a pre-arranged backline. A backline, as defined by the production pros we spoke with for this article, is essentially all the equipment that you, as a band, need to play a show. It’s usually either provided by the promoter that has hired you to play, or you’ve provided a backline supplier with a rider that lays out exactly what your band needs to execute your set just the way you want. But that latter situation is usually reserved for bands that are already operating with quite a bit of success. If you’re just starting out and you don’t have the dough behind you to have a supplier set you up for every gig, it’s more likely that the first time you run into questions about backline will be in the context of a festival or showcase.

Case Jumper, the live events manager of backline supply company and rehearsal studio Soundcheck Nashville, lays out the way things go down for the Country Music Association’s summer extravaganza, CMA Fest.

“We do five small stages of backline, then we do the River Stage, which is a larger package, and then we do Nissan Stadium,” Jumper says. “So, on the smallest stages, CMA says, ‘Look, we need something where bands can come up, play, get off, and get the next band on in 30 minutes.’ It has to be a very quick turnaround, and that means that it has to be things that people are going to play and use. So for something like CMA Fest, on the small stages, you’re probably going to get a Nord keyboard. There’s going to be a Fender Twin, there’s going to be a Vox AC30, there’s going to be a [Fender] Deluxe [Reverb], and then there’s going to be probably a Gallien-Krueger bass rig, and then an assorted drum kit with cymbals. I give them those specs, and then they use that in their advance with bands. With something like the River Stage, which is still that same format of ‘quick-on, quick-off,’ but it’s a little bit larger scale, we up it. There are multiple key rigs but also a Hammond B3 and Leslie, and a pretty giant drum set. Sometimes we do a grand piano, and then the amp range goes more. So there’re Peavey Nashville 400s, there’s a Marshall JCM900 rig. There are Voxes, Twins, maybe some Deluxes, probably a Roland KC-550 keyboard amp. It just becomes a larger thing. For the stadium, we basically build it out per band. Then we get into specifics of riders, where we’re doing exactly what they’re asking for.”Here are some of the most common pieces you’ll see on backlines in Nashville. Do you know how your guitar and effects rig sounds through them?

Vox AC30

Fender Twin Reverb

Fender Deluxe Reverb

Marshall JCM900

Gallien-Krueger bass amp

Peavey Nashville 400

Nord keyboards

Hammond B3 organ

“For the stadium, we basically build it out per band. Then we get into specifics of riders, where we’re doing exactly what they’re asking for,” says Soundcheck Nashville’s Case Jumper.

Photo by Case Jumper

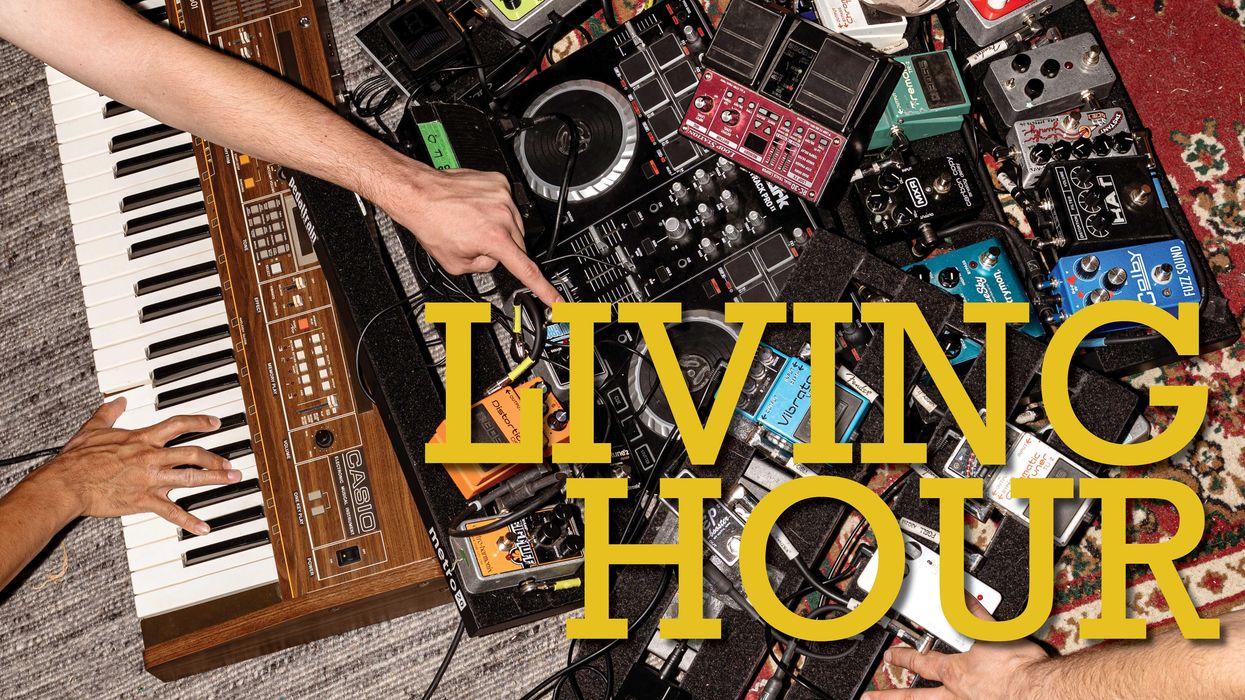

The equipment provided in a backline changes in every situation, but generally a band can expect that, onstage, they’ll be provided amplifiers, drums, and microphones. Depending on your needs, you might also have a keyboard and keyboard amp, and some stands. Generally it’s up to your band to bring your guitars, basses, pedals, and your drummer’s breakables, plus snare drum. But because the situation differs with every gig, it’s best to have an in-depth conversation with whoever is providing backline so that no one is left high and dry without the gear they need to get through the show. Some things get overlooked more than others. When we asked Jumper to tell us the most important thing for guitarists and bassists to remember about dealing with backlines, he immediately provided a pro tip: “Bring your cables!” And capos, he adds.

When it comes to the specific amp brands and models that one might expect from a typical backline which has been put together without artist input, Jumper notes a few common examples. In Nashville, AC30s, Twins, and Deluxe Reverbs are nearly ubiquitous. In Los Angeles, players might be more likely to find Marshall and Mesa/Boogie rigs. “Depending on what the sound of the area is, I think that dictates which amps you’re going to use,” says Jumper. “Bass rigs are another prime example. Ampeg SVT rigs may be more prevalent in Nashville, where Aguilar might be more prevalent in New York and L.A. And maybe Gallien-Krueger and some of the more funk rigs are more prevalent in Atlanta. Then Texas is its own market. It’s such a mix.”

It’s a good idea to figure out how your rig interacts with Fender Twin Reverbs, because you’ll encounter plenty of them on backline gigs.

Photo courtesy of Fender

Vox AC30s come up often in Jumper’s responses, for good reason. He notes that they’re incredibly versatile, which makes them great for many situations.

"You can go very clean, but very loud, still [with an AC30],” he says. “And then it works well, because most players are coming in with a pedalboard system. So while some old-school, L.A.-type players might still use the gain structures from a Marshall head or a Mesa head, most of the people are doing that all internally now.”

On that note, Jumper has noticed that in Nashville many players have been moving away from guitar amps altogether and opting instead for modelers and profilers like Kempers and Fractals.

“It’s a unit, much like a keyboard, where you say, ‘I’m looking for this particular sound,’ and you can plug in and it’ll get you very close to that sound,” says Jumper. “So maybe you’re a touring guy, and you’re having to do lots of flights—instead of trying to work with a backline company to make sure they have all your exact amps in every city, you might invest in a Kemper, and outfit the Kemper to sound exactly like you want. That way you’re just rolling into every venue with an SKB case instead of wondering what you’re gonna get.”

If you’re a backlinin’ bass player, you should probably know your way around Gallien-Krueger amps, like these Legacy 800 heads.

Photo by J.B. Stuart, SIR Phoenix

It’s worth pointing out, too, that every company is different, and some backline providers don’t necessarily advise clients about what they should use in specific situations, or build one-size-fits-all sort of packages. Some companies, like Studio Instrument Rentals [SIR] in New York, work pretty much strictly with equipment riders provided by bands or promoters, putting together their preferences exactly. So it’s also best to know exactly what you might need to ask for if you know you’ll be in a situation where backline rentals will make up a large part of your on-stage gear.

The best way to get that in order is by writing out an equipment rider. Jumper notes that it’s important to keep that rider constantly updated in order to avoid unnecessary confusion come gig day, pointing out that plenty of artists just forget to update riders after they’ve made changes in their sound.

An equipment rider is exactly what it sounds like—a document that very clearly lays out all the gear you’ll need to play a show. It will certainly contain the number of pieces per gear you’ll need (e.g. two guitar amps, one bass amp, etc.), but it should also note preferred brands and models, as well as brands and models that will work if your preferred amps are not available; wattage and power specifications; sizes of speakers; drums and drum sizes; and microphone preferences, if you have them. Essentially, you want to get down to the nitty-gritty of what must be on stage to pull off a great show. With a detailed equipment rider, backline pros can solve problems more quickly, giving them the tools they need to improvise when your preferred amp or mic isn’t available locally.

Do you have an equipment rider and stage plot for your band? Those are the first steps to getting ready for pulling together your own backline.

Photo by William O’Leary, SIR New York

Another document that works either alone or in tandem with a detailed equipment rider is the stage plot. As noted above, it’s not necessarily common that you’ll run into a situation where you’re able to simply ask for everything you want. But you will definitely wind up in situations where a stage manager needs to know how to set everything up. The stage plot is a visual document that indicates how gear should be arranged. This should include the placement for microphones, amps, drums, keyboards, and any other instruments, helping a stage manager quickly discern where band members will be standing or sitting.

If you’ve got any worries about your potential backline situation, or communication with the promoter leaves you with more questions than answers, it might help to generally expect workhorse gear. As Jumper says, in this part of show business, reliability is key—the aforementioned AC30s and Fender Twins are reliable, as are solid-state bass rigs. So it’s likely that you’ll encounter this gear on the regular. It could be a good idea to get familiar with these pieces and how your specific rig interacts with them.

And, of course, if you do get the privilege of working directly with a backline supplier, clear and friendly communication goes a long way to making sure your big gig goes off without a hitch.

“When people are coming to Soundcheck, I want them to ask how I can help them make their event, whether it be a festival or one-off, run as smoothly as possible from a backline perspective,” Jumper says. “I obviously can’t run it all, but I can make it so our gear is not faulty, you know—we’re not the chain that breaks. That allows artists to focus on whatever else they’re having to worry about. They know that Soundcheck is always going to provide top quality equipment, and they’re always going to provide people to make sure it works right.”

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)