Larkin Poe, the fiery roots-rock band fronted by sisters Rebecca and Megan Lovell, have managed to achieve something that so many touring bands never do: They feel content with their level of success. In their case, that includes a Grammy for Best Contemporary Blues Album, for 2022’s Blood Harmony; packed-out headlining shows at many of the best-sounding clubs and theaters in the country; and delicious, nutritious prepared foods.

“We don’t necessarily need to sell out Madison Square Garden to be like, ‘Oh, we’ve made it, we’re a success, mom,’” Rebecca chuckles. “We’re a lot more comfortable at this point in our lives and our career with truly defining what success means to us. Being able to have houses, roofs over our heads. We’ve got the cash that, if on tour we want to stop and pay for the Whole Foods hot bar, we can do that. That’s luxury enough for me, at a certain point.”

“I was sort of playing catch-up for many, many years. I still feel like I’m playing catch-up.”—Rebecca Lovell

That sense of modesty and self-awareness is admirable, though when it comes to making new music, Larkin Poe continue to swing for the fences. Their latest album, Bloom, which the sisters co-produced with Rebecca’s spouse, guitar slinger and vocalist Tyler Bryant, represents both a continuation and striking progress. Throughout these 11 tracks, Larkin Poe deliver the driving, stomping grooves and post-Allmans interplay that have made them buzzworthy torchbearers for electric blues and blues-rock. With Megan on electric lap steel and Rebecca on a Strat, their guitar-frontline dynamic has become as intuitive and instinctive as their harmony singing. “We’re constantly ‘foiling’ for one another [on guitar] … acting as a foil,” says Rebecca. “So if I’m going low then she’s going to automatically go high, and vice versa.” Rebecca, who also handles lead vocals, describes her sister’s keen ear with awe. “I can sing something at Megan onstage and she can immediately play it back to me,” she says. “She’s so comfortable with her instrument.”

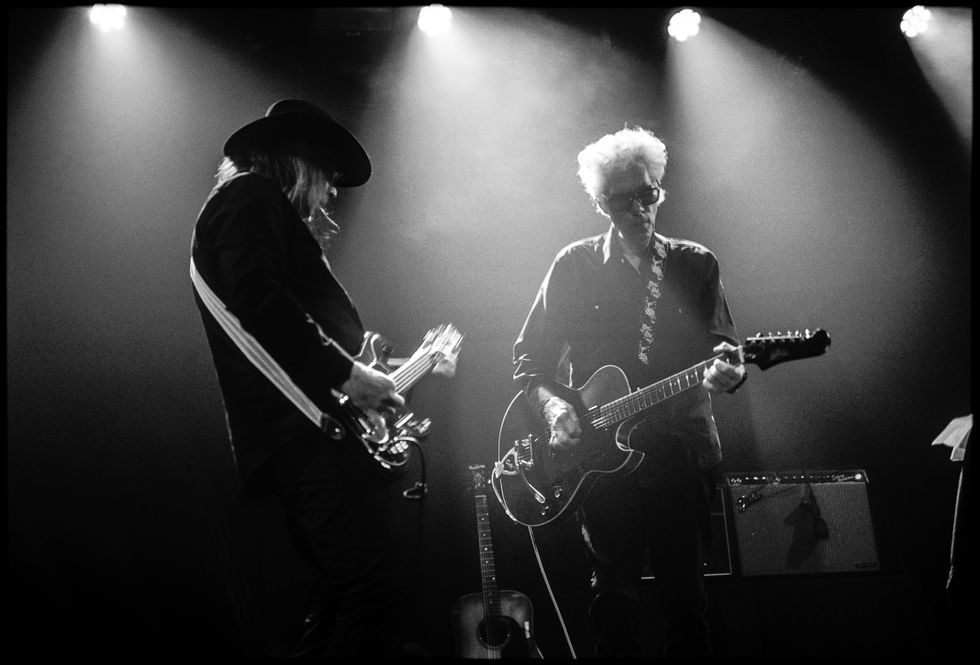

On Bloom, sisters Megan and Rebecca Lovell continue their mastery of southern music, from bluegrass to Allmans-style boogie to blues rock.

“I was sort of playing catch-up for many, many years,” Rebecca adds. “I still feel like I’m playing catch-up.”

Where Bloom really ups the ante is in its songcraft, in terms of both the depth of expression and sheer number of earworm hooks. In “Mockingbird,” “Little Bit,” “If God Is a Woman” and other standouts, bits inspired by ’70s singer-songwriters and rootsy Music Row pop elevate the sisters’ rock ’n’ soul. To say it another way, with these songs Larkin Poe could open a tour leg for Taylor Swift and absolutely kill, preaching their gospel of blues-soaked guitar heroism all the while. Many, many online orders for entry-level lap steels would ensue.

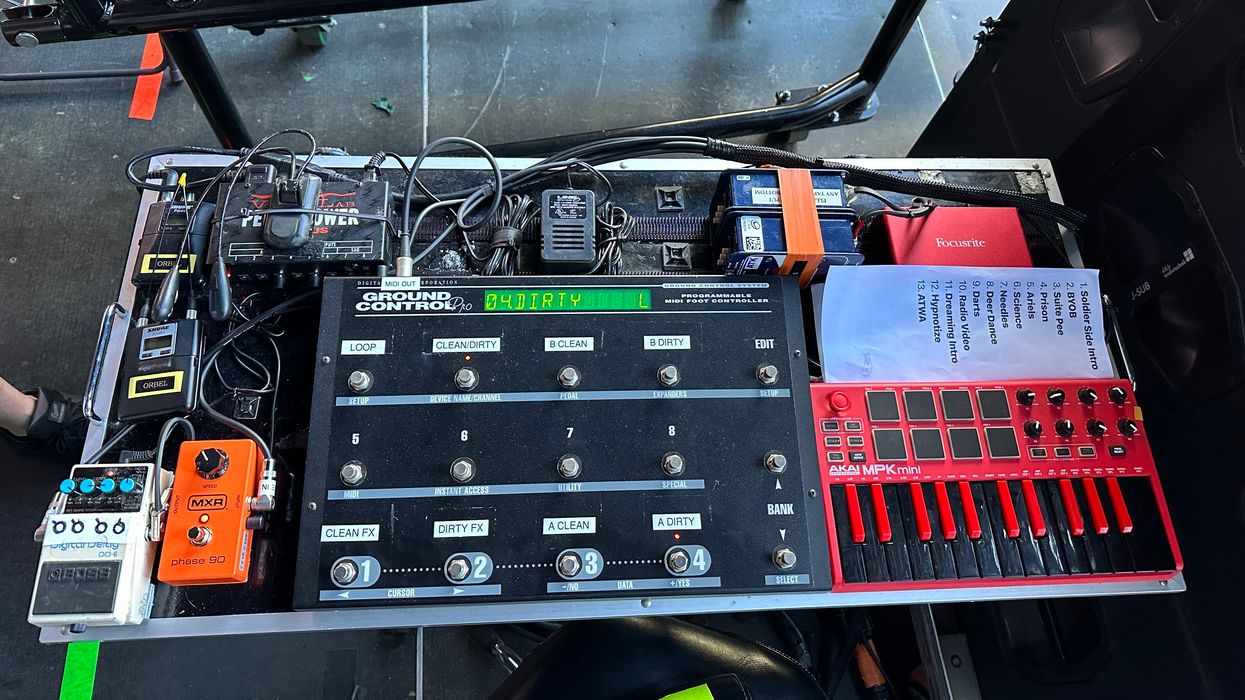

On Bloom, Rebecca explains, “I do think the songwriting was the center of the creative process, which it always is. But I think that we were especially meticulous in writing for this record.” The songs were built from the ground up, in a spirit of absolute collaboration shared among the Lovells and Bryant. What’s more, the sisters, both now in their 30s, became comfortable enough to dig deep and reflect on their lives with candor. “Somebody will come up with an idea,” Megan says, “and it’s really neat this time around being able to set aside some of the … I don’t know what was stopping us before—sibling rivalry? Who knows what it is?Rebecca Lovell's Gear

Guitars

- ’60s-style Fender HSS Custom Shop Stratocaster

- 1963 Gibson SG

Amps

- Fender Princeton

- Fender Champ

- Square Amps Radio Amp

Effects

- Vintage Roland Space Echo

- MXR Phase 90

Strings & Picks

- Dunlop .60 mm pick

- Ernie Ball Coated .011s

“I think you have to be especially vulnerable when opening yourself up to write a song with people, and Rebecca and I have always struggled with that a bit over the years. But it was like some sort of a veil fell away and we were able to come together in a way we hadn’t really before.”

“I think you have to be especially vulnerable when opening yourself up to write a song with people, and Rebecca and I have always struggled with that a bit over the years.”—Megan Lovell

If you’ve followed the rise of Larkin Poe, it might be hard to believe that Rebecca and Megan could get any closer. Born in Tennessee and raised in Georgia, they entered music through classical training but made their names as two of the three Lovell Sisters, an acoustic unit grounded in bluegrass. As Megan explains, “Bluegrass is the foundation of the way we put riffs together and the way we approach our musicality.” To this day, she calls square-neck resonator hero Jerry Douglas her foremost inspiration as a player, and she believes bluegrass set a standard of musical excellence that the sisters have retained in Larkin Poe. “My expectation of what I should be able to do is quite high,” she says.

Growing up, the sisters absorbed a broad range of music at home: During our chat, the name-checks include Ozzy Osbourne, Alison Krauss, Béla Fleck, and the Allman Brothers, whose albums Rebecca pretty much used as a guitar method. Her more recent 6-string influences include her husband and other Strat masters like Stevie Ray and Jimmie Vaughan. “I can hear how much of a Bryant flavor I do have,” she says with a laugh. “Which is kind of cute, maybe kind of sad. I don’t know. The internet will decide.”

Megan Lovell's Gear

For Larkin Poe, success sometimes looks like the hot food bar at Whole Foods while on tour.

Photo by Zach Whitford

Guitars and Basses

- Beard Electro-Liege

- Amps

- Tyler Amp Works Dumble clone

Effects

- Electro-Harmonix POG

- Universal Audio Starlight Echo Station

Strings & Picks

- Dunlop Zookies thumbpick

- ProPik fingerpicks

- Scheerhorn stainless steel tonebar

- D’Addario .013–.014s

Almost 15 years ago, Rebecca and Megan came together officially as Larkin Poe, refocusing on Southern blues-rock and, over the years, fostering their love of profound country-blues like Skip James and Son House. “We didn’t stand in front of amplifiers until we were 16, 17 years old,” Rebecca says. “For many years, it was so startling to stand in front of any amount of wattage. That was something that has definitely taken some time to really get used to.”

“We’ve had just enough taste of what the top feels like to know that happiness lies wherever it is that you put it.”—Rebecca Lovell

Perhaps because of their background reveling in acoustic tones, the Lovells’ amplified sound is bliss for anyone who adores the undiluted sonics of excellent guitars plugged into well-crafted, overdriven tube amps. In our age of mile-long pedalboards and amp modelers, the Lovells remain closer to the ideal that Leo Fender and Jim Marshall had perfected by the mid-’60s. “Megan and I are pretty militant about never doubling or stacking guitars,” Rebecca says, “and we are trying to create big, fat sounds between just the two of us.”

Bloom was captured at Tyler and Rebecca’s no-frills Nashville studio, the Lily Pad, with a small but mighty arsenal of no-nonsense axes and amps. The goal, as ever, was to bottle the energy and ambiance of the live show. Rebecca tracked using low-wattage tube combos and her trusty HSS Fender Custom Shop Strat. Megan, who plays primarily in open G (G–B–D–G–B–D), relied on the Electro-Liege she developed with Beard Guitars and a Dumble clone by Tyler Amp Works. “It was the best tone on the record,” Megan says, “and I could never get away from it.” The holy grail sound for her, she explains, is David Lindley’s “Running on Empty” solo. “Having come from the acoustic background,” Rebecca adds, “we’ve always been very sparse in terms of effects pedals.”

It’s a humble, self-aware approach to gear that savors the fundamentals. What else would you expect? More than anything, the Lovells’ greatest gift might be their ability to understand what’s actually important. “We’ve been doing this now since we were young teenagers,” Rebecca says, “and we’re on a slow-burn path, buddy. We have played shows to just the bar staff. And we’ve had just enough taste of what the top feels like to know that happiness lies wherever it is that you put it.”

Late last year, Larkin Poe cut a live performance for the German television show Rockpalast. Enjoy the full, blistering 80-minute set.

Though both heavy players in the soul and funk world, Feingold and Hunter first met via Instagram.

Though both heavy players in the soul and funk world, Feingold and Hunter first met via Instagram.