After nearly 30 years as the only constant member of drone-doom-metal cult heroes Earth, guitarist Dylan Carlson has released his first album, Conquistador. As the title suggests, the work espouses a fantasy world that's rooted in history, not unlike the one explored on Earth's 2005 Hex; Or Printing in the Infernal Method—a belated imaginary soundtrack to novelist Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian. Carlson has also done soundtrack work, under his solo moniker drcarlsonalbion, for the film Gold. But this time, the music speaks exclusively to his personal vision.

Carlson has always been known for wading against common trends—an approach that's helped him define his voice in the sparse, expansive sound of Earth. Like most artists, he's proud of not fitting into a mold. “I make records for people. I don't make records for guitar players," he says. But it's not an exclusionary statement, just one that acknowledges the detachment he takes from the technical and cultural associations with the instrument while songwriting. Drawing heavily from his tastes in film and American history, he gradually and steadily builds a world on the all-instrumental Conquistador in which he becomes more of a visual architect than a guitarist, exploring the negative space between rich, textural tones.

The minimalist, ambient compositions on Conquistador rely on the subtle personalities of Carlson's guitar tones, which he achieves with a lot of patience, trial and error, and the perfect combinations of gear. Though, he admits, gear is not as important to him as it used to be. “There's no magic box or magic amp. It's all you, for better or for worse," he laughs. Even so, he keeps a particular family of pedals—“discovering compression was a godsend"—and has refined, over the course of his career, the routes to creating the precise hues of distortion to furnish his sonic world. On the album, he worked with producer and Converge guitarist Kurt Ballou, and is accompanied by his wife, Holly Carlson (who's also the model on the cover), on percussion, and Emma Ruth Rundle on baritone and slide guitars.

What inspired you to write your first solo album?

We had finished a lot of touring with Earth, for our last record for [L.A.-based label] Southern Lord, and we had just changed management. I had some ideas for some songs, so it seemed like a good opportunity to get into a studio and get some music done. The idea originally was in the vein of Hex, which was sort of a soundtrack to an imaginary film, and the other soundtrack I did for the movie Gold. Conquistador is also sort of Western-themed, and a soundtrack to an imaginary film. Since soundtrack work is something I'm really interested in, I hope to get to do another one at some point, but until then, I guess I'll keep doing imaginary film work. [Laughs.]

So if Conquistador is a soundtrack to an imaginary film, is that film a Western?

The era that Conquistador envisions is during the initial collision between Europe and the New World. When I was in junior high, I lived in Texas, and we had a Texas history class where I read about a conquistador. He had a Moorish squire named Esteban, and they went to what was then Northern Mexico, now the American Southwest, and got lost for 20 years. They had a bunch of, I guess you could say … “adventures" where they were sold into slavery by one tribe and escaped, and worked with another tribe—basically, things didn't go as planned. The album was more based on this memory of the story rather than the specific text. I've also been influenced by a number of my favorite films, like The Fountain by Darren Aronofsky. So it was a bunch of little things all bubbling around.

TIDBIT: Produced by Converge's Kurt Ballou, Conquistador includes Holly Carlson on percussion—and on the cover—and guitarist Emma Ruth Rundle.

Is your guitar playing usually guided by that kind of visual experience?

I've always been visually oriented when it comes to guitar playing. When I first started, I'd find patterns on the guitar and see how they sounded, as opposed to being an ear player. And as I've progressed, I've become much more of an ear player. Also, since the title is the only verbal cue to describe the narrative arc of the song, I'm very conscious of the way the title looks or sounds. I'm always trying to look for something evocative, 'cause I've always believed there still needs to be narrative arcs to the songs—even songs that I do with a lot of repetition. I believe that there should be a narrative arc to the record as well, which I feel is something that's a bit lost with the advent of the CD, and now digital media. It's the order of the songs that makes a great album, as well as the songs themselves.

How do you give your music a narrative arc?

Usually it's through textural cues. I've always been interested in subtle dynamics in music. The thing that always bugged me about grunge is it reduced musical dynamics to “here's the quiet part and here's the loud part," and I've always preferred music where the textures and the interplay of instruments build small crescendos and dynamics in that way. The intensity in the playing, you know? And then I was lucky in that Emma Rundle joined me to add her music to mine.

I've definitely always been a believer in that approach—where if you limit the options in certain things, it forces you to become more creative with what you have. I'm also a strong proponent of what I like to call “happy accidents."

What is the ratio of improvised versus composed music on the album?

I don't know … 80/20? [Laughs.] The riffs were there, but the structures were done in motion. And then a lot of it had to do with the fun of looking for guitar tones. Some songs are more composed than others, but even with the ones where there's a strong compositional presence, I've always believed in leaving room for improvisation. The most composed song is the last song of the album, “Reaching the Gulf." There's the basic riffs, but then the arrangements sort of happened naturally as I played them in the studio, so they have much looser organization. Which, again, I think helps with the narrative arc of the record, because it's about leaving, heading into the unknown, and then stuff happening that you don't foresee, and then the return at the end to a controlled environment—or at least a more controlled environment.

What is it that draws you to repetitive patterns?

I'd always hear stuff in other songs and be like, “that's a great riff, why don't you just keep going with that rather than immediately jumping to another one?" I always liked Indian music and psychedelic stuff and, obviously, blues. Maybe it's this atavistic thing from my Scotch heritage, like the bagpipe or something. [Laughs.]

How was it working with Emma and Holly on the album?

I played a show with Red Sparowes and Marriages, bands Emma was playing with, and I borrowed some of her gear that night. And then she's on [our label] Sargent House, and my wife, Holly, and Emma got along quite well. I think she's a fabulous musician and she really added a lot to the proceedings. Holly was travelling with me at the time, and we needed extra percussion. She played piano when she was younger and sang in choir. She was also a dancer, a belly dancer, so she has good rhythm [laughs], so that's sort of how that happened. It was also my first time working with Kurt Ballou, which was really enjoyable. He has a cool studio and a really good ear and a lot of helpful ideas. At the same time, he doesn't force them on you. He's really open to your ideas. And then he has a lot of interesting equipment. But it was a very easy record, in a lot of ways, because it flowed quite well and everything that needed to get done got done. I enjoyed it. I hope other people do, too.

YouTube It

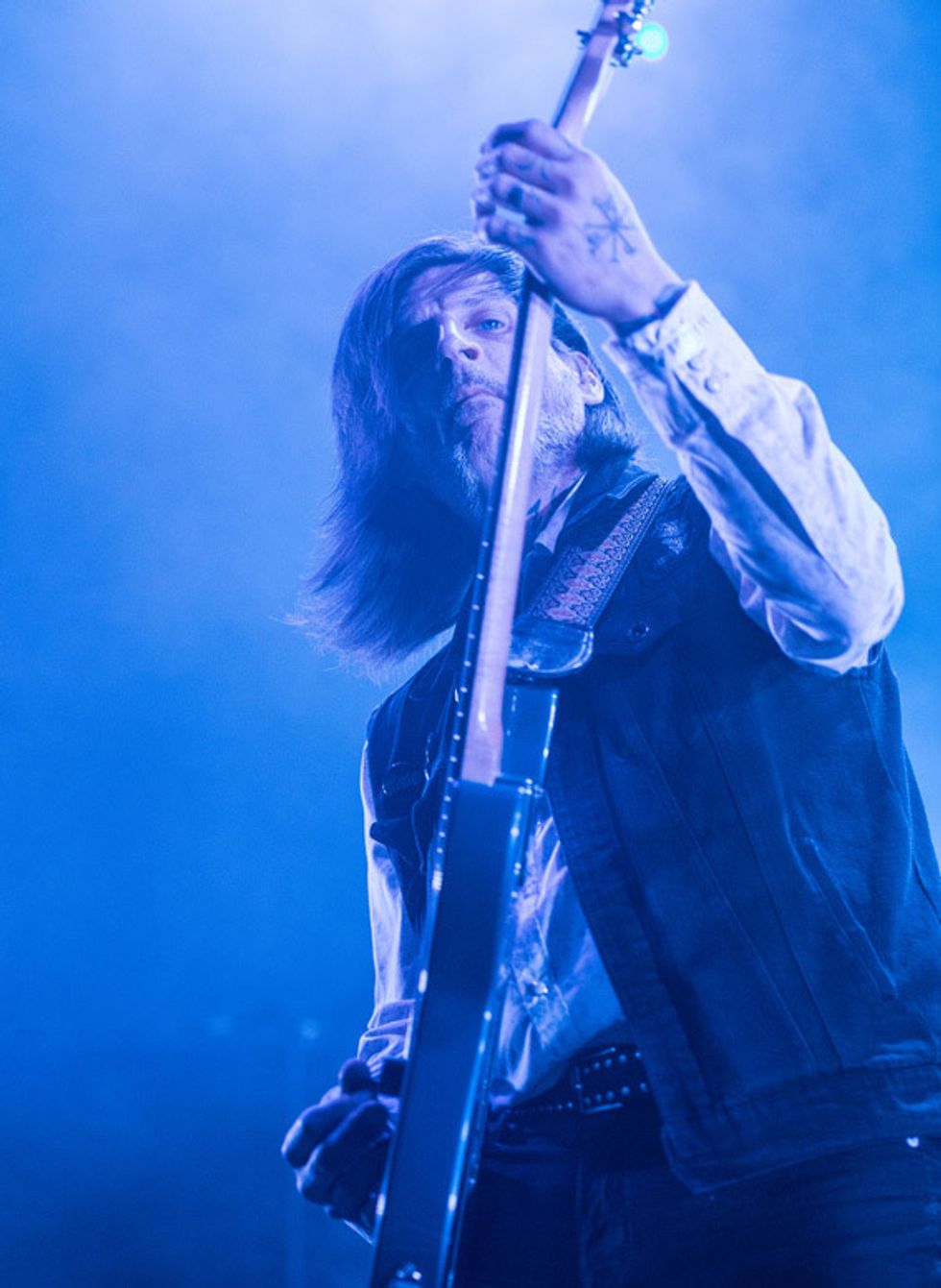

Dylan Carlson trips the light electric with his Fender Squier Strat, beefed up with a DiMarzio bridge pickup, at a 2013 gig in London. The deliberate playing approach caught here is also at the core of his new, all-instrumental Conquistador album.

Father Earth: “I've always felt like the thing that really motivates me is, 'Is the riff something that's worth repeating, and does it convey my conception of the song?'" says Carlson. Photo by Tim Bugbee/Tinnitus Photography

Let's talk about gear. How important is your gear to the songwriting process?

I'm much less gear-centric than I used to be. I realized over the last few years that no matter what I use, I'm going to get my sound and be me. And obviously, there's slight variations based on gear choice, but I realized I could have saved myself a lot of time and money in the early days.

What guides your preferences?

I don't like a lot of pedals. I think there's almost too many to choose from nowadays. [Laughs.] I see some people's pedalboards and I'm, like, confused. I think some of the prices on gear lately are ridiculous. You don't need to spend $10,000 to sound good. I've always been a big MXR fan. I use a Custom Comp, which is the sort of nicer version of the Dyna Comp. I love the regular Dyna Comp, too, but I find that the Custom Comp has a lower noise floor. And then I like the Shin-Juku Drive for distortion. Then, I just got this HBE Dos Mos, which is a dual MOSFET preamp. I really like it because it allows me much more textural options, where the distortion becomes a texture, too, so I can also do a loud cool sound. In the studio, I'll end up using more modulation to separate the tracks and to color them. Live, I reduce the number of effects I use.

What about amps?

I've actually gone solid-state. [Laughs.] I have a bunch of tube amps lying around and they all need servicing and are annoying to carry around. Right now I'm using a DV Mark 50-watt solid-state head, and I have a Crate Power Block solid-state head. I think a 50 watt is the largest head you'd ever really need. You're never gonna get to the sweet spot on a 100-watt head, you know? We all grew up with pictures of Hendrix with these huge amp stacks, and that was because they were playing without PAs. Nowadays, you don't need to do that.

One of the best shows I think we ever did was opening for Neurosis in London, and I was playing an old WEM Dominator, which is basically a 15-watt amp. People were saying how great we sounded that night, and no one thought we were too quiet or not loud enough. Because a 15- or 30-watt amp will scream. People seem to forget that you double the wattage of the amp and you're only increasing the actual volume by 3 dB. All you're increasing is your headroom. If you want the harmonic enrichment, you have to drop the headroom.

Dylan Carlson's Gear

Guitars

Fender Squier Stratocaster with DiMarzio Cruiser bridge pickup

Fender Highway One Telecaster with DiMarzio Tone Zone bridge pickup

Amps

DV Mark Micro 50 head

Crate Power Block

Ampeg SVT 210AV cab

Dietz 1x12 cab

WEM Dominator MK III 15-watt 1x12 combo

Effects

Korg Pitchblack Tuner

MXR Custom Comp

MXR Shin-Juku Drive

Dunlop Uni-Vibe Stereo Chorus

CKK Electronic Q Cat envelope filter

Homebrew Electronics Dos Mos Dual MOSFET Pre-amp

Tym Guitars Engine of Ruin distortion

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Regular Slinky (.010–.046)

Dunlop Premium Celluloid Heavy

And guitars?

I guess my favorite guitar would be the Tele. Right now I'm on a bit of a Strat jag. I've played other guitars, but I always seem to come back to the Fender style. I find them the best for touring, 'cause they have the straight neck instead of the angled headstock, and they're not finicky. They get the job done and they take the road really well—whereas set necks and headstocks that are angled are accidents waiting to happen.

How did you first get into guitar?

My parents were into music, so I grew up with a lot of music around me. But no one really played an instrument. And then when I got into music, as in buying my own, AC/DC was the first band I got into, and that's what made me want to play rock 'n' roll, I guess. For a long time, I wanted to play guitar, but never really got around to it. Then one day my dad suggested it, so I bought one finally on my 15th or 16th birthday. A good friend of mine at high school who was a big prog-head showed me a few chords, and that was sort of my beginning. I immediately started trying to write songs rather than learning other peoples' songs. I taught myself the rudiments of theory. Although, the thing I've always tried to remember is, the music comes first—the theory grew out of that, not the other way around.

What influences your guitar playing?

I'd have to say the guitarists I really gravitate to serve the music or serve the song—people like Steve Cropper or Cornell Dupree. I've always felt like the thing that really motivates me is, “Is the riff something that's worth repeating, and does it convey my conception of the song?" I always find it very interesting when people talk about a song I've done, and they'll say it's similar to something I may have thought about the song, and the landscape I may have envisioned for it.

Earlier you mentioned how the music industry on the whole has somewhat lost sight of the album. Do you think this would ever shift your approach to your own music?

When I was young, Buzz from the Melvins was talking to me and he said, “There's two ways to do things." He was speaking specifically of music, but I guess it could apply to other things. “You can try to jump on the trend, or what's happening at the moment, and you might succeed famously, but you might not. Whereas, if you do what you do and you just keep doing what you do, eventually people are going to pay attention to it, hopefully."

I've always tried to follow that advice. I just do what I do, and just try to keep doing what I do, and it's obviously not the quick route, but it's seemed to work up to this point. I haven't had to take advice from record labels, or play songs by hit songwriters I don't know or don't like, or dress up in clothes I don't want to wear. You may not have a mansion on MTV Cribs, but you can go to sleep at night and look at yourself in the mirror, hopefully.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)